#326 Up-Island with E.J. Hughes

June 21st, 2018

E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island

by Robert Amos, with the participation of the Estate of E.J. Hughes

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2018

$35 / 9781771512558

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

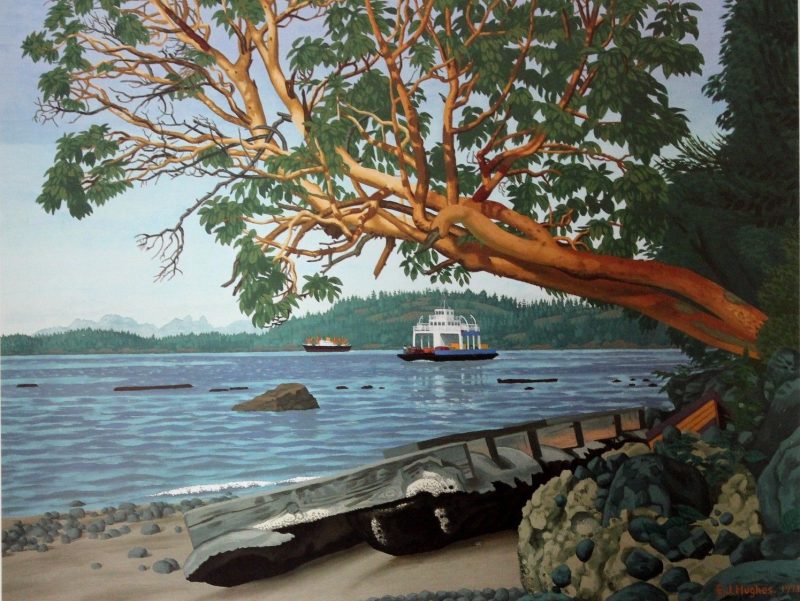

It’s not easy to paint an arbutus tree, although many artists try. Know in Washington State as Pacific madrone, the arbutus (Arbutus menzeisii) above the 49th parallel grows only where it chooses in the dry southeast regions of Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, and in select waterfront spots on British Columbia’s lower mainland. In life, its astonishing beauty overwhelms its eccentricities, but in a painting its twisted limbs and angular postures appear impossible; the more accurate the drawing the more unlikely it appears.

In my viewings, I find two artists who have succeeded in capturing the arbutus (always excepting Emily Carr whose renderings of anything are not like anyone else’s). One is the subject of this book, E.J. Hughes. The other is its author, Robert Amos, who is both an artist and an art writer.

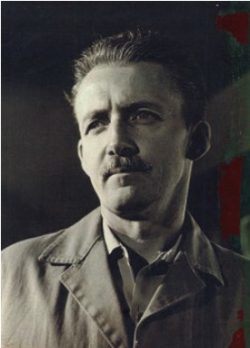

E.J. Hughes (1913-2007) has become one of Canada’s most popular artists: “popular” as in widely admired and “popular” as in widely accessible — to tastes if no longer to pocketbooks. While he lived most of his life not far from his birthplace of Nanaimo, his work went further afield. He was represented by Max Stern of Montreal’s Dominion Gallery, who came west in 1951 in search of another Emily Carr and found instead someone completely different but entirely satisfactory. Several retrospectives honoured Hughes, the most impressive at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2003 accompanied by a splendid comprehensive publication E.J. Hughes by Ian Thom (Douglas & McIntyre, 2003). This new book, E.J. Hughes paints Vancouver Island brings new insights and a more intimate experience.

During his years (1975-1980) as Assistant to the Director at the Art Galley of Greater Victoria and later as art writer for the Times-Colonist (1986-2018), Robert Amos became acquainted first with the work of E.J. Hughes and then with the artist himself. The most memorable of Amos’s newspaper columns went beyond interviews and became informal artist-to-artist conversations, often within his subject’s working space amongst the works in progress.

A series of photo-collages of artists in their studios developed into one of Amos’s most successful books, Artists in their Studios; Where Art is Born (TouchWood, 2007), featuring informal glimpses into the working lives of 32 Vancouver Island artists, including Robert Bateman, Pat Martin Bates, Carole Sabiston, Zhang Bu — and E.J. Hughes. Amos’s generous and genuine interest has earned him the trust of artists and their associates and access to archival materials waiting for an informed and sympathetic biographer. His biography of Harold Mortimer-Lamb, also published by TouchWood, appeared in 2013.

So it was made sense that Pat Salmon, described by Hughes as his “biographer, friend and chauffeur” and by herself as his “traffic control,” should turn to Amos when she realised she was not going to complete the biography which Hughes had entrusted to her. With the agreement of the Hughes family, she made available years of carefully compiled notes, interviews, photographs and other documents. Amos calls this book a “first step” towards a complete biography. He is also working on the Catalogue Raisonnée of the art works of E.J.Hughes.

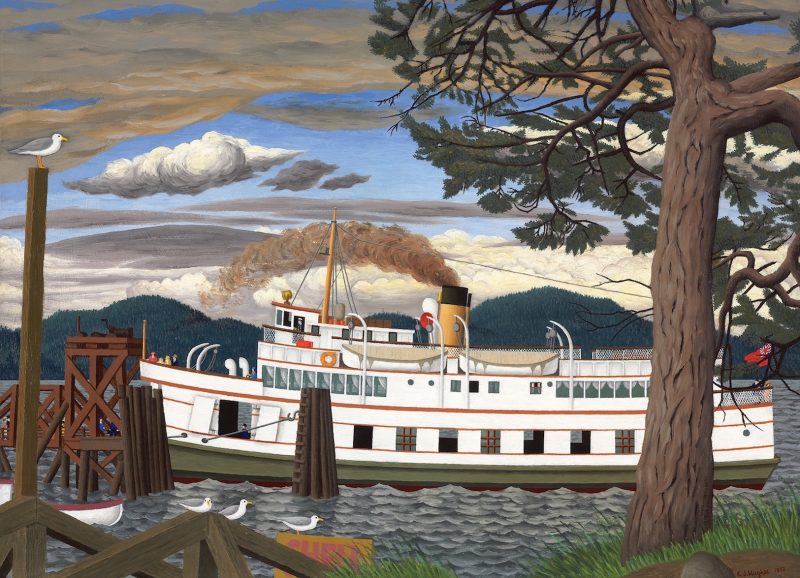

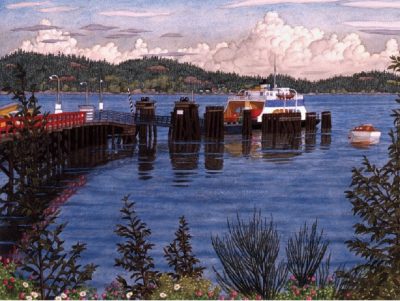

In this first step, Amos takes us on a tour of Hughes’s home terrain. The itinerary is geographic, not chronological, and begins in the south of Vancouver Island, with “The Car Ferry at Sidney” (1952). Unlike Amos, whose most frequent subject is Victoria, Hughes did not paint the city itself, and “almost every place he visited after 1967 was … easily accessible by road as a day trip from his home at Shawnigan Lake or Duncan.” “We proceed up island to Goldstream and the Malahat Drive, past Bamberton and Cherry Point to Cowichan Bay, Crofton, Chemainus, Ladysmith, Nanaimo, Qualicum, and Courtenay,” with brief hops over small stretches of water to Salt Spring and Gabriola Islands, and only once an excursion to Breaker Beach on the far west coast.

Our guide prepares us for the tour with an introduction and an extensive biographical essay — early days, art education, stints as muralist and war artist, family life, the progress of his art career and reputation, the reclusive tendency beginning well before the death of his wife Fern in 1974, and his later years on Vancouver Island. Amos also provides a helpful section on Hughes’s painting technology and various media — oil, acrylic, watercolour, and sketches.

Then come about sixty paintings, accompanied by Hughes’s hitherto unpublished handwritten notes, with preparatory sketches and smaller reproductions of earlier or later interpretations of the same sites. We are shown exactly where Hughes parked and where, from the privacy of his car drew, and annotated the beginnings of works to be recreated in the studio — where meticulous jottings would be transformed into something rich and strange, something which is not quite realism.

Amos quotes Adrian Chamberlain, Gabriola Islander and Times-Colonist arts writer, puzzling over a scene he thought he knew well:

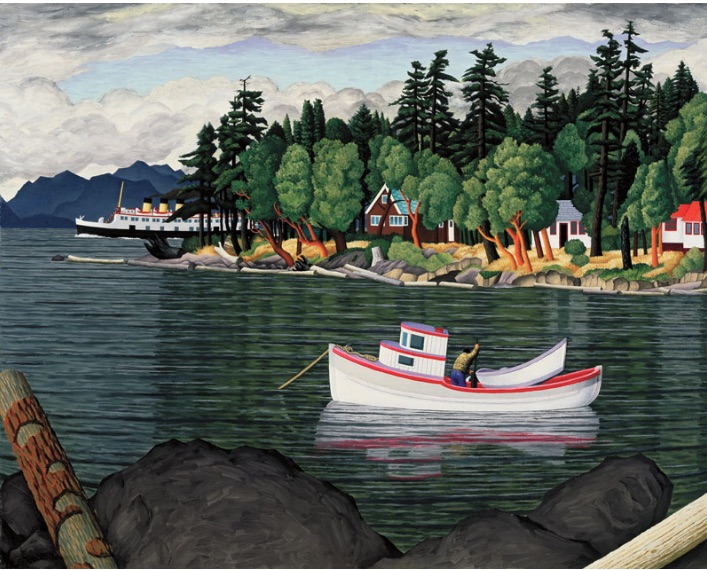

Taylor Bay, Gabriola Island (1995) at first glance seems a naturalistic depiction. Yet because the landscape is so familiar to me, I know everything is compressed and highly stylized… An oddly abstract handling of details — funny little things left in, others left out — produces a spectacularly heightened effect. The impression is not reality. Instead, Taylor Bay is recalled as a powerful dream. [See Taylor Bay painting at the end of this article.]

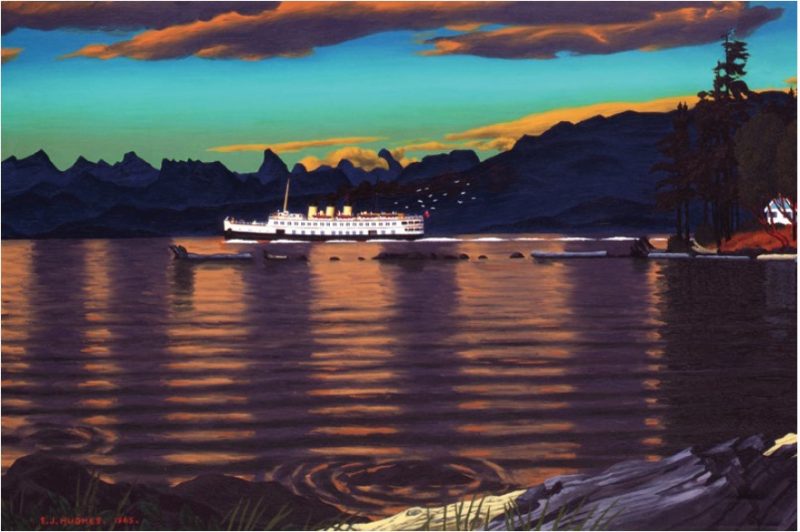

But sometimes what appears to be a dream, even a nightmare, turns out to be realistic. The painting chosen for the cover, “Passing Coast Boat” (1965), another view of the Gabriola waters, Amos judges “perhaps the most lurid canvas Hughes ever painted,” an evening scene invented from the artist’s memory and imagination.

I agreed, until the other day when a fellow islander posted a photograph to the Gabriola Community Facebook page. The colours and mood caught by the camera were as lurid and impossible as those “invented” by the artist.

Landscapes, shorelines and streets are simultaneously recognizable and strange. Vehicles and small boats can be identified by genre, brand and sometimes specific name; yet they bounce with something close to personality. The large vessels of BC Ferries, on the other hand, have seldom looked so splendid in detail, so at home in these waters, and so much a necessary part of the scene.

The people in the paintings at first seem to lack faces, but as we continue to look we discern what they are doing and how they are feeling. And there are many of them, and animals and birds as well. In one painting, “View of Qualicum Beach,” Amos counts 87 people and three dogs. In “Departure Bay,” he finds sixty seagulls, one clearly portrayed, the others illusion.

He invites us to follow his expert gaze to admire plants portrayed in almost botanically precision, for instance in “Ferry at Crofton, B.C.” (1992), “a filigree of beautifully rendered Nootka roses and broom,” and of course the magically precise “Arbutus Tree at Crofton Beach|” (1973).

This illusionary realism, this conscious and sophisticated “primitivism” was the personal style of a slight dapper gentleman who drove a Jaguar and looked more like a small town businessman than an artist. The relationship with his biographer is less a matter of adulation or influence than affinity, a shared love of this coastline perceived as art. Their friendship and mutual respect make this book more personal than most coffee table volumes, and offer us a sort of double exposure invitation, to look at our world not only through the eyes of one artist but also through the eyes of another artist looking at the first artist looking at that world.

How might that affect our own perception, the next time we look at a BC Ferries vessel or an arbutus tree?

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She also contributed the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website: https://sites.google.com/site/phyllisreeve/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply