The unforgettable Major Matthews

As a neophyte poet, John Pass became the confidante of Major James Skitt Matthews, a windbag of the first order.

January 25th, 2018

Major Matthews 1936. George T. Wadds photo. City of Vancouver Archives.

Bizarrely, in 1969, John Pass was hired to take over from Vancouver’s first archivist, an Imperial bulldog from the late Victorian and Edwardian eras.

*

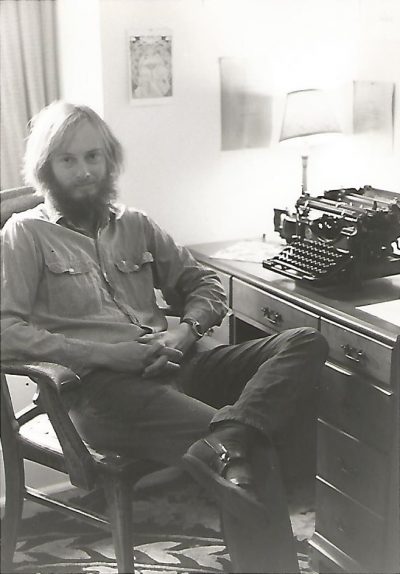

We are pleased to unveil a memoir by the award-winning poet John Pass (born 1947) from the summer of 1969 when he crossed paths with Major James Skitt Matthews, a legendary figure in Vancouver’s history.

That year John Pass was somewhat haphazardly chosen by Matthews (1878-1970) as his replacement. As Pass reveals, the position turned out to be both far more ephemeral and far more substantial than it first appeared. City Hall officials were trying to outwit the crusty and increasingly senile Major–so Pass would be gone by the end of the summer. But Major Matthews and his eccentric archives and opinions proved unforgettable.

“I knew enough then of what a poem required to sense that what I was picking up in the Vancouver Archives was pure gold,” Pass writes.

Major Matthews, once upon a time, was legendary. Fiercely protective of his work, Matthews remained an avid and cranky local history maven and collector until his retirement at age 91 in 1969. He died the following year. Unofficially and officially, James Skitt Matthews had been the City of Vancouver’s chief historian for almost 40 years. He always flew the Union Jack at his home on Sundays and holidays. – Ed.

In July of 1969 I was hired by the City of Vancouver to be trained as its next, and its second, city archivist. The circumstances of how a 21-year-old with a newly minted but unremarkable degree in English entered upon such an impressive career begins with a help-wanted ad I’ve been unable to trace.

To the best of my recollection, my mother called me up (as was her habit in my student years in those early-summer weeks of despondent idleness) with the helpful, essential details: a young man with a BA was wanted to train as Vancouver City Archivist. One was to apply to City Hall.

I must have called rather than written as I can’t find any trace in the archives’ files, nor in my own, of a letter of application. I must have been told that the present archivist would like to meet me, not at work, at the Main Branch of the Vancouver Public Library, but at his home, for lunch, because I found myself at table shortly thereafter in the home of Major James Skitt Matthews of Kitsilano.

The Major sat to my left, I think, and to my right sat Wesley Black, B.C.’s Provincial Secretary.

At least that’s the way I’ve always told the story. I can find no trace in the Major’s papers of the event although there is evidence in his correspondence of a meeting with Lawrie (Lawrence) Wallace, Deputy Provincial Secretary, sometime that July. Maybe it was Wallace I lunched with, or Black and Wallace.

To the west, through the front room windows, I could glimpse Kits Beach past a hedge between the road and the house, and trees across the road in the park. In the immediate foreground, looking south into Matthews’ triangular garden at 1158 Arbutus St. on Kitsilano Point, the scene was intersected by a lower segment of the pole from which he flew the Union Jack.

Two other people, the Major’s female assistant from work and his housekeeper/cook, were present. The table was set with white linen and silverware, flowers too as I recall. I wasn’t interviewed, not even questioned beyond the polite inquiries of luncheon conversation. Had I enjoyed studying at UBC? Did I live in Kitsilano? Everyone smiled and nodded.

I was introduced and toasted as the city’s next archivist by the Major himself, a short, solidly squarish figure with fierce eyebrows. He wore the garb of a Victorian gentleman at lunch, dark suit and waistcoat complete (I fancy now) with pocket watch, and made murmurs and noises throughout the meal, rising to his feet unexpectedly on several occasions to produce commanding but dislocated snatches of speech and recitation the rest of the company seemed used to and tolerant of. He spluttered a little, was clearly senile, but with a directness and bravado that suggested he had no idea himself of his condition. His place at the head of the table was uncontested. He was his own man. I didn’t know what to make of the situation but it was the late Sixties and I was becoming acclimatized to an off-kilter strangeness in daily life. I thought it might be not too difficult, and some fun, to be an archivist.

I had to go to City Hall to fill in the requisite forms for employment and was surprised to be ushered into a room with at least two, possibly three, gentlemen awaiting my arrival.

Could my hiring really warrant this degree of interest and formality? They seemed a little confused or uncomfortable, but pretty well directly told me, after some mumbling about the unfortunate wording of the help-wanted ad, that I should understand that I was not to be the city’s next archivist.

The job offered was for the rest of the summer only and the gist of it, emphatically albeit obliquely communicated to me by each of my interviewers in turn, was that I was to pretend to be Vancouver’s next archivist in training. The ruse was to humour the Major, who wouldn’t retire until he’d personally trained his replacement. It was a kindness to the old man, an indulgence by the city of his whim. A gesture of respect. There would be a new archives soon, with a professionally trained archivist recruited to head it up. It was important that I understood the situation, and that I didn’t reveal the ruse to the Major. It would only upset him. I did understand, didn’t I?

I didn’t really. Not then. Later I learned that the city was waiting out the nearly 91-year-old Matthews, even unto death. Much later I learned that my hiring was a tired gambit in a decades-old struggle between entrenched opponents and that even my role as archivist-in-training was an old one. Matthews had hired assistants to train on numerous occasions. I was merely the last potential archivist, with the added wrinkle that the city had contrived, and that I knew from the outset, that I’d never ascend to the position.

That July morning, looking across at my interviewers, their embarrassed smiles and dissembling busyness with papers and files, I believe I saw only a job to see me through to September. I don’t remember feeling disappointed or even much surprised. I certainly had no other immediate plans. And I had some acting experience. I signed up.

Time capsules. Major Matthews at right and a Box of Jokes,1953. W. Cunningham photo. City of Vancouver Archives.

Of what did my archival training consist? There were two regular duties that I recall. The Major would come down to the library two or three days a week only, and only for an hour or two at a time. I would meet his taxi on Burrard and help him, via the staff entrance, a small elevator lobby to the north of the main doors, onto the elevator to the third floor. With his firm grip on my arm we would then proceed along the forward edge of a sizable, windowless, flourescent space cluttered with artifacts of purported historical significance: lamp standards and business and street signs, bits and pieces of farm equipment, decrepit office furniture, churns and washboards, heavy glass electric insulators….

To our left, we passed through a partitioned office area with a table and filing cabinets to enter his office at the front of the building with a window onto Burrard and barely enough room for him to edge around the immense desk of a former mayor and settle in his swivel chair. Off that room to the library building’s north corner was the archives proper, a little warren of library stacks, narrow corridors between metal bookshelves.

My other duty was a daily one. For some part at least of my six weeks or so at the archives I lived in an apartment on Nelson in the West End. Upon reporting to work, I would immediately return to my Yamaha 80 motorcycle and ride over the Burrard Bridge to City Hall on Cambie for the mail.

A clerk who managed the mailboxes would hand me the packet of letters and newspapers and I would ride back to the library with it safely tucked up under my denim jacket. After a few weeks and some serious discussion among the Major and his two elderly assistants, I was permitted, instead of checking in first, to go for the mail on my way to work and arrive at the library at twenty minutes after nine. I don’t know why it didn’t strike me as odd at the time that mail for the archives would have to take this circuitous route to its destination. I later discovered that the procedure was a little knot in the nutty and convoluted struggles between the Major and the city.

Vancouver’s archives, the voluminous and haphazard collection of letters, papers, pamphlets, transcripts of memoirs, newspaper-clippings, memorabilia, and artifacts I delightedly muddled about in that summer, were actually owned by Matthews himself. His relationship with the city administration was uneasy at best, at times volatile. He received a modest stipend in acknowledgement of the historical importance to Vancouver of the collection and the city had bestowed upon him the title, Archivist, in 1933, some years after he had bestowed it upon himself.

From 1933 to 1959, the archives had been housed in moderately satisfactory digs in City Hall. Then archivist and archives were, in the Major’s estimation, banished to the library, really only warehouse space, certainly not adequate for display purposes, nor inviting to the general public. Matthews hated it. His oft-expressed disgust is illustrated in this quote from a letter to Mrs Stanley Williams:

Please do not address me at the Public Library; I hate the place, and the very name of it. All our mail still goes to the City Hall; we call for it there each morning. We have a very large and wide list of correspondents, institution (sic) in Australia, United States, British Isles. I don’t want them to know that the City of Vancouver has its repository of treasure in the same building as a PUBLIC Library, a place which announces that they lose 500 or 1000 books each year by theft. It is too terrible to reflect upon. Imagine the comprehension of these lunatics at the City Hall who put us here. However, it had its purpose. I think it so shocked thinking men and women that it set in motion a plan to change it; to give us our own building. I have been toying with the thought of refusing to receive any mail addressed to us at the Public Library, and instructing the postal authorities to return it to the sender as “not known at this address.”

His relationship with City Hall deteriorated to the point that he threatened upon numerous occasions to bequeath everything to the Queen (and send the entire collection to London) if the city did not build him a proper archives. The present arrangements were clearly unsatisfactory and an embarrassment to a city with pretensions to the “world-city” status it would be stridently asserting a decade or so later. And a new, properly professional archives was planned for a site adjacent to the new Maritime Museum, across Kits Park and northeast along the beach from the Major’s home. He was not part of those plans.

In the course of writing this account forty years later, frustrated in my search for corroborating evidence of my first meeting with the Major and my hiring at City Hall, I awoke in the middle of the night with a new strand of possible enquiry dangling before me. Maybe Black, or Lawrie Wallace, being significant government officials, had appointment books or correspondence in which a luncheon with Matthews would be noted.

I called my son Forrest who’d just defended his Ph.D. in History. He’d know the way to such records if they existed. In a matter of minutes, our family’s newest and first properly trained historian came up with specifics on the internet: no appointment books but a file in the BC provincial archives of correspondence between the Provincial Secretary’s office and Matthews, 1961-69.

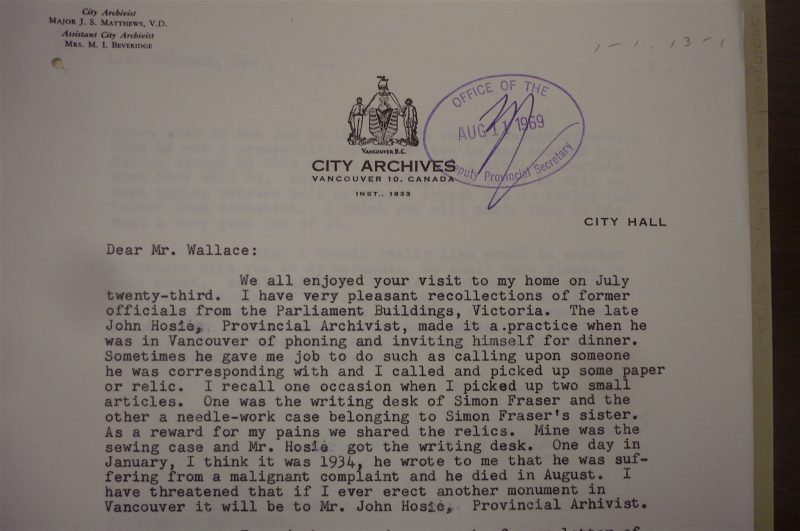

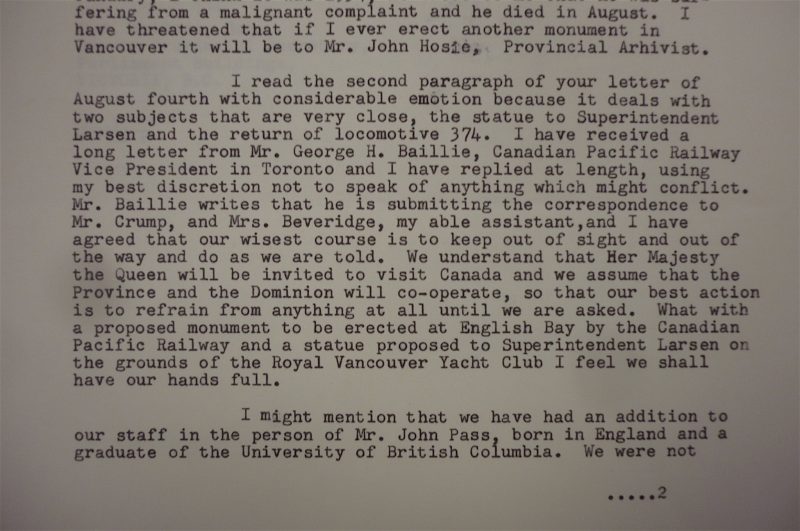

In the Provincial Archives in Victoria a few days later I found myself with a letter in hand from the Major to Wallace, undated except as received, stamped August 11, 1969, Office of the Provincial Secretary. Its opening sentence, “We all enjoyed your visit to my home on July 23rd” grabbed my attention, but it was the third paragraph, beginning near the bottom of page one and continuing on a second page, that revealed more than I could have hoped for:

In the Provincial Archives in Victoria a few days later I found myself with a letter in hand from the Major to Wallace, undated except as received, stamped August 11, 1969, Office of the Provincial Secretary. Its opening sentence, “We all enjoyed your visit to my home on July 23rd” grabbed my attention, but it was the third paragraph, beginning near the bottom of page one and continuing on a second page, that revealed more than I could have hoped for:

I might mention that we have had an addition to our staff in the person of Mr. John Pass, born in England and a graduate of the University of British Columbia. We were not aware when he met you on the veranda that pleasant afternoon that he was a prospective Archivist but he has assumed his duties though at this moment we are all a little uncertain what they will be. But of one thing I am sure; he will do some typing because he’s an expert typist and is taking this letter from dictation. I think you will admit that he has made a very good job of it.

So it was lunch, or maybe only afternoon tea on the veranda, on July 23rd with Deputy Provincial Secretary Lawrie Wallace. My 60’s memory had been imperfect, but I’d been there!

So it was lunch, or maybe only afternoon tea on the veranda, on July 23rd with Deputy Provincial Secretary Lawrie Wallace. My 60’s memory had been imperfect, but I’d been there!

What, exactly, the Major meant saying “we were not aware” at the luncheon of my being a “prospective archivist,” or what I must have thought typing those words, I can put down only to Matthews’ senility. How had I magically “assumed my duties” if I had not been at least a “prospective archivist” at lunch? How else had I been invited? He’d forgotten I’d been toasted that day as his replacement, and I must have been too shy or already too protective of his pride to point out the error in the letter as he dictated it.

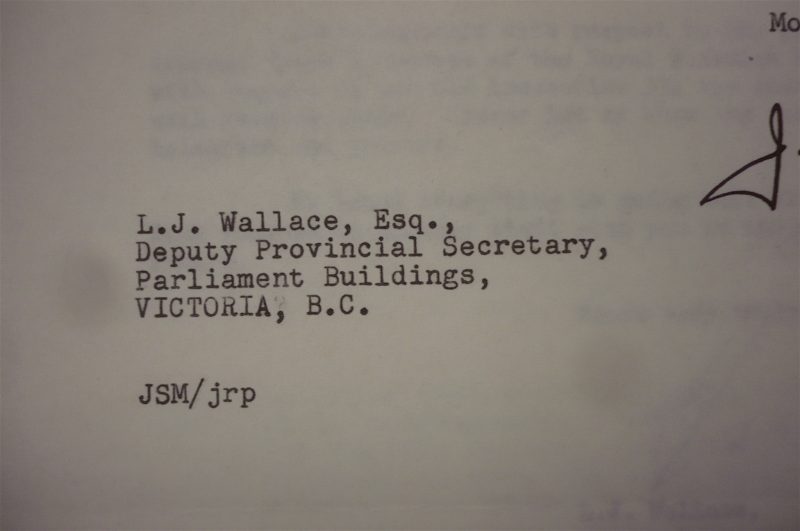

At the letter’s end in the lower left hand corner, in the code then used when letters were dictated and typed, there appeared the Major’s initials and my own: JSM/jrp. The expert typist might have remembered to date an outgoing letter but otherwise I did appear to have “made a very good job of it.” I’d likely spent some hours doing so, hunting and pecking with index fingers as I’d done for my course essays and fledgling poems over the previous undergrad years.

At the letter’s end in the lower left hand corner, in the code then used when letters were dictated and typed, there appeared the Major’s initials and my own: JSM/jrp. The expert typist might have remembered to date an outgoing letter but otherwise I did appear to have “made a very good job of it.” I’d likely spent some hours doing so, hunting and pecking with index fingers as I’d done for my course essays and fledgling poems over the previous undergrad years.

I later noticed my initials at the bottom of another BC Archives letter from Matthews, signed with his name per M.I. Beveridge, his assistant. Dated July 28th, this one doubtless preceded the other, as the 28th, a Monday, was probably my first day at work; but why, I wondered, hadn’t I seen copies of these in the Major’s outgoing correspondence files at City Archives? Had the expert typist neglected to make the standard carbon copies?

Here at any rate was a third responsibility I’d had in my career as archivist beyond those remembered of picking up the mail and helping the Major in and out of his taxi and the library elevator. I had typed at least two letters. What else did I do or learn there?

Here at any rate was a third responsibility I’d had in my career as archivist beyond those remembered of picking up the mail and helping the Major in and out of his taxi and the library elevator. I had typed at least two letters. What else did I do or learn there?

I cut up daily newspapers. This seemed to be the archives’ raison d’etre. Yesterday’s Vancouver Sun, which was then an afternoon paper, and the morning’s Province, fell under Mary Beveridge’s scissors first thing in the morning each weekday. I was asked to assist and did the cutting acceptably I believe, once I was told what and where to cut. I was not trusted, however, with the filing of the cut-out articles, and I am sure I could never have mastered that aspect of the archival work I saw so ably conducted there.

The sophistication and complexity of the Major’s file system was confounding. The expertise required to navigate it was most strikingly illustrated to me those days when Bessie Bolton, Matthews’ housekeeper, dropped in as she sometimes did, to keep Mary Beveridge company, to have tea and help out with the morning’s work. Between bites of biscuit and sips of Earl Grey, with just-snipped excerpt in hand, Bessie might say to Mary, “Maclean, Broughton St. Has run into a tree.” To which Mary would reply, “Grandfather was Richard, engineer. No! … He was an accountant. Goes in the CPR file.”

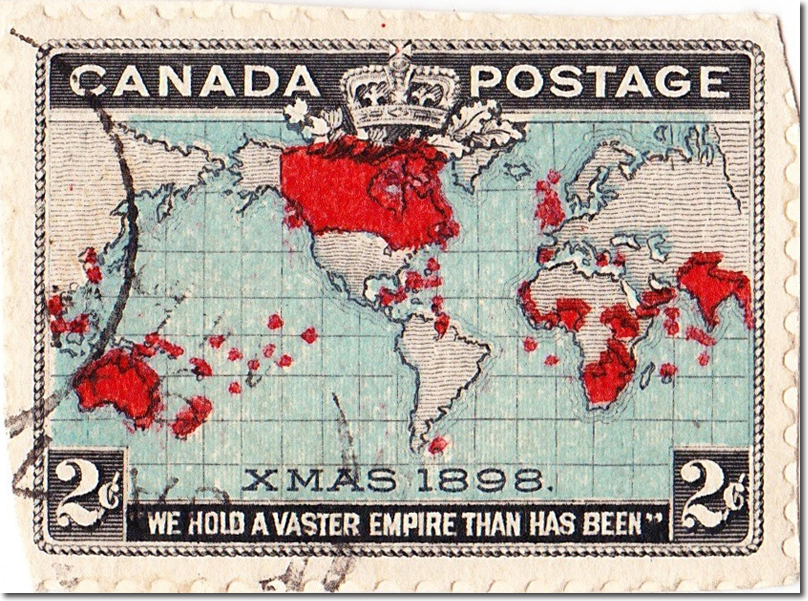

I never got the hang of it. But the CPR file was as voluminous and central to the Major’s collections as the railway was in his historical imagination. I had my own CPR “file,” of course, as did every kid growing up in this country in the fifties, details of that massive undertaking that enabled confederation. From sea to shining sea.

But the Major had a different take on it. The creation of Canada, which he called the Dominion to his last day, was secondary to the British imperial quest. For him, the last spike at Craigellachie forged “the last link in the red route around the world,” tying Britain’s North American colonies at last to her Asian ones via sea lanes to Hong Kong, Singapore, India.

For most Canadians, this perspective on the country and Vancouver’s place in it must have been out of fashion by the end of the First World War; but if we substitute the contemporary and largely corporate constructs of the “Pacific Rim” and “Cascadia” for the Victorian world map expansively ruddied with British colonies and interests, Vancouver’s importance has increased exactly along the geographical lines the Major celebrated.

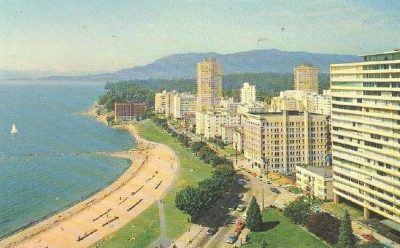

And I found his vision oddly instructive. The city I knew in the sixties was attempting in a fervent, clumsy, adolescent way to be more cosmopolitan, less the end-of-the-line sleepy backwater the rest of the world saw. In contrast to Victoria, many of whose citizens were still proud of being more British than the British, Vancouverites increasingly saw their city as a bustling business centre, an important port.

The West End was being transformed from gracious Victorian houses and low-rise brick apartment blocks into high-density glass and steel skyscrapers. In the suburbs, where I went to high school, new subdivisions were climbing up the hillsides and across the Fraser Valley farmlands. There was a freeway to take people downtown and some of my fellow high-school students, for whom downtown had always been New Westminster or Port Coquitlam, actually made the trip to Vancouver for the first time in their lives in that decade.

Lifted on the development boom, people were moving in and out of those suburbs at a pace unknown in the settled districts of Mount Pleasant, Shaughnessy, and Dunbar. In Point Grey, the rapid expansion of the university saw staid family residences renting rooms to students. In Kitsilano, around the corner from the Major’s 1920s-era stucco bungalow, Haight/Ashbury north with its headshops, Advance Mattress coffeehouse, and Retinal Circus discotheque was in full swing on Fourth Avenue. On Granville Island theatre performance spaces and lofty restaurants were being carved out of warehouses.

But I appreciated the Major’s take on the city. It contributed to a depth, a grounding, I’d begun to seek in the place I lived, a counterpoint to the pushy and superficial sea-and-ski paradise vision holding sway in the high-rise office towers and real estate brochures. He suggested some substance behind the light show.

My most tangible link today to my time in the Vancouver Archives is a handful of publications the Major gave me. Mostly pamphlets, on topics ranging from Narvaez’s arrival on the B.C. coast in 1791, through the founding of the Salvation Army in Vancouver in 1887, to the opening of the first gasoline filling station in the city in 1907 (the Major worked for Imperial Oil at the time), to the re-dedication of Stanley Park in 1964, they are a fascinating portal into his archival work.

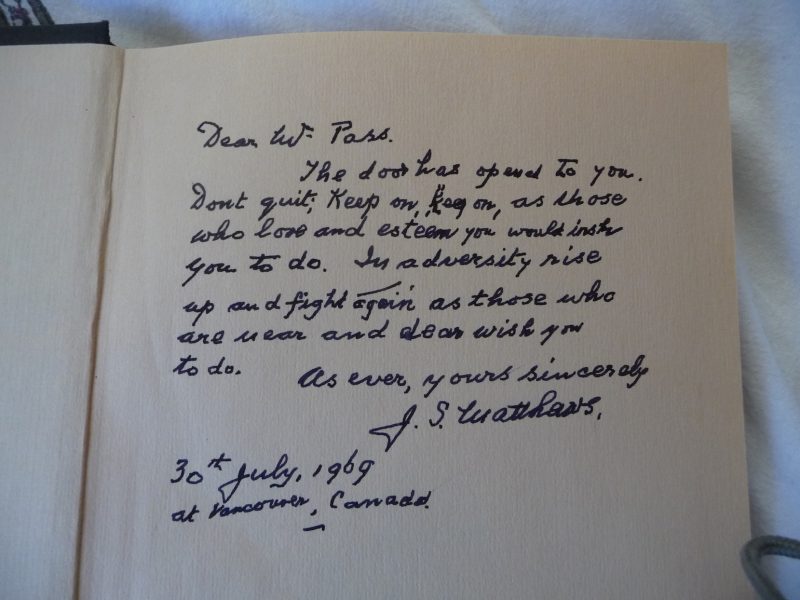

The most impressive of these publications is a hardcover copy of Early Vancouver (Vol. 1, 1932), which the Major inscribed as follows:

The most impressive of these publications is a hardcover copy of Early Vancouver (Vol. 1, 1932), which the Major inscribed as follows:

Dear Mr. Pass.

The door has opened to you. Dont quit; Keep on, keep on, as those who love and esteem you would instruct you to do. In adversity rise up and fight again as those who are near and dear wish you to do.

As ever, yours sincerely

J.S. Matthews,

30th July, 1969

at Vancouver, Canada.

At the time I was more nonplussed than touched by the sentiment. Having met at lunch exactly one week earlier, and the 23rd and 30th July that year being Wednesdays, this gift was proffered on what was likely my third day of work and the first occasion upon which the Major and I were in the archives together.

I’d met no adversity on the job so far, though those “near and dear,” my father in particular, who’d been a Royal Engineer in the Second World War, might have offered similar advice, encouragement, admonishment — what exactly?

It had the ring of British imperial stoicism, echoes of Kipling and Tennyson, not entirely unfamiliar, nor welcome, to my ears. The gravity of the call to duty was somewhat leavened by Matthews’ clumsy punctuation and capitalization: the sober black ink, the crossings-out, the uncrossed t’s, the half word “instr” hanging at the end of a line, an abbreviation for “instruct.”

I treasure this inscription today for its comical and excessive romanticism and as a poignant marker of Matthews’ determination, persistence, and adherence to a world-view that enabled so much remarkable pioneering accomplishment. It’s a rhetorical tic, of course, the phrasing recurring in his writing, most tellingly from my perspective in a letter of condolence to Provincial Archivist John Hosie’s widow when Hosie died unexpectedly in 1934.

His provincial counterpart had been a stalwart supporter of Matthews’ efforts to establish a Vancouver archives, and at a particularly low moment in that struggle the Major says Hosie encouraged him by bellowing in his ear the words, “don’t quit now man, keep on, keep on.” Despite the sentiment’s timeworn ubiquity, I treasure most its echo in my direction, not as something I fall back on in adversity, though we all have that to face and can use support from any quarter, but as a gesture from the Major’s old age toward my just commencing life’s work and purpose, whatever that might become.

He was right. A door had opened to me.

Matthews’ writing — grandiloquent, disorganized, repetitive — is also an inspired and inspiring tapestry of Vancouver’s first decades. While the city might not quite have arisen “from stumps to skyscrapers in a generation,” it had had that remarkable genesis over the Major’s lengthy lifetime.

Although skewed towards the chronicling of epic events in the Imperial narrative — such as the “Great Vancouver Fire” of 1886 (which burned in 45 minutes a “city” all of 68 days old consisting of a few two-storey wood-frame buildings and several blocks of sparsely scattered cottages and sheds), or the heralded arrival of the CPR (really only an afterthought branch-line from Port Moody where the railway first touched the Pacific) — his interviews with pioneers are invaluable chunks of history.

His editing, from clumsy to none at all, has preserved their authenticity. They have texture, real life. And they were the ideal complement and antidote to a budding poet’s recent immersion in undergrad literature courses, in texts relentlessly edited and interpreted over decades if not centuries.

I read Matthews’ publications cover-to-cover, hungry suddenly for a beginning of my own from the city’s first days. I read them for the particulars, the quirky details, the puzzling digressions, maddening omissions, and bizarre emphases from which imaginative reverie springs. They offered tantalizing beginnings everywhere!

I read Matthews’ publications cover-to-cover, hungry suddenly for a beginning of my own from the city’s first days. I read them for the particulars, the quirky details, the puzzling digressions, maddening omissions, and bizarre emphases from which imaginative reverie springs. They offered tantalizing beginnings everywhere!

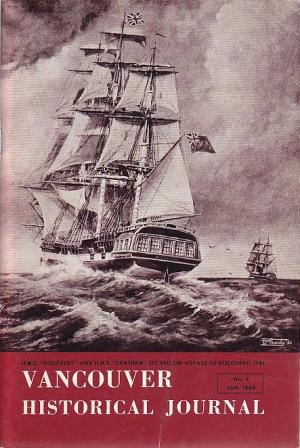

The handsomely produced Vol. 3 of the Vancouver Historical Journal, for example, begins with 65 pages or so on the 1886 fire, skips through some photos and early sketches of the West End, alights briefly (one page) upon the unveiling in 1960 of Lord Stanley’s statue in Stanley Park, offers full page snaps of the St. Roch and her captain Henry Larsen completing their final journey into Vancouver (1944), and concludes with the 24-page section “Capilano Creek, Discovery of Source, 1890.”

Or almost concludes. The last couple of pages are devoted to “The Remarkable Unveiling of Cleveland Dam and Capilano Lake,” specifically the unveiling in 1954 of the plaque on the dam honouring Ernest Cleveland, the Greater Vancouver Water District’s First Chief Commissioner.

Just as the Union Jack is lifted from the bronze, the Major’s prose soars. After 94 pages, here is the concluding sentence of Vol. 3:

Just as the Union Jack is lifted from the bronze, the Major’s prose soars. After 94 pages, here is the concluding sentence of Vol. 3:

The suddenness of the change from the dismal oppression of thick fog to a lovely scene of blue lake, green trees, and, in the distance, the white snow-capped mountain, was almost miraculous; it was as though nature joyfully participated in a tribute to the works of man and joined in doing honour to the distinguished civil engineer, the late Dr. Cleveland, who first climbed Grouse Mountain as a youth.

With considerable effort we might cobble together a narrative from this volume’s trajectory. The city’s 1950s water requirements could, albeit tenuously, link back to an early emphatic need for fire protection … and then dash forward, via that sketch of the West End from the waters of False Creek and the conquest of an ice-free (hence watery) North West passage aboard the St. Roch … to the Capilano River and Lake … water-ways adjacent to Grouse Mountain! (Though Grouse is not, alas, “the snow-capped mountain” visible at the end of Capilano Lake from Cleveland Dam. That would be the twin peaks of the Lions, and too much connective tissue to expect of the Major’s muscular but disembodied prose.)

Was Cleveland the first to climb Grouse, or does mention of his youthful hike at The End imply mysterious, sacred import, the climb foreshadowing nature’s complicity in the ultimate “unveiling”? So much better that no compelling storyline is present! This was history in flood, o’er-brimmed with possibility. Come swim in conjecture it called to me! With very little else to do I dived in, and poked around in the files and dockets and stacks like a treasure-diver in a wreck.

Stranded some afternoons onshore beside his expanse of desk I listened, uneasily at first but contentedly at length, to the Major rumble and blunder about in his hoard of anecdotes and assertions.

I liked hearing him fulminate, for example, on the universal mispronunciation of Burrard, that the man for whom the street was named would be livid to hear us put the accent on the last syllable, Burrard. It was Burrard. Looking out the window onto Burrard I appreciated for the first time how Van Horne’s grid of narrow streets, laid out in defiance of geographic idiosyncrasies for every city the CPR ran through, was constraining and directing Vancouver traffic and building (one-ways and high-rises) nearly a century later.

I opened with appalled and bemused curiosity (yes, exactly that unlikely combination!) the yellowed, dusty pamphlet in the stacks that warned the women of the city against the Yellow Peril, specifically how their purchase of carrots and cabbages from Chinese market gardeners may be saving them a few pennies but threatened western civilization.

I loved discovering that Governor General Lord Stanley had not managed to be present for the opening of his park by Mayor Oppenheimer in 1888 because “he must be at Quebec on the date named.” Making the trip and dedication a year later, Stanley may or may not have intoned the resonant words inscribed on the statue’s pedestal below his beneficent all-embracing stance: To the use and enjoyment of people of all colours, creeds and customs for all time. I name thee, Stanley Park.

All the source material I could find about Stanley’s sojourn in Vancouver emphasized not the park but the city’s enthusiasm for the transcontinental railway that had delivered the great personage west and promised unbounded prosperity. Stanley did visit and dedicate the park, but no definitive record remains of what he might have said.

Matthews interviews Frank Plante, owner in 1889 of the only hack in town, who drove Lord and Lady Stanley out to what is now Prospect Point. Plante remembers a speech, but more specifically he recalls a bottle of wine that he had had in his carriage appearing on the podium and being poured, partially, upon the ground to consecrate the moment. He remembers too, at Matthew’s prompting, that he, Plante, had not a drop of that wine!

If Stanley’s dedication involved more than the bottle tipped or a glass lifted, it’s surprising we can’t read the speech now in some original form. Every other public word surrounding the visit seems to have been dutifully reported by the newspapers of the day. In the city proper en route to the park, for example, it’s reported that Stanley rose before the populace to say that he was proud to be there and to know that there was “a place without a grievance,” an ambiguous comment at best and, although apparently embraced as praise by his audience, not at all foreshadowing in tone or content the high oratory of the speech he’s supposed to have given an hour or two later at Prospect Point.

The Major commissioned the statue inscribed with that high-flown language. I deduced — via shrugs, nods, and meaningful glances between Mary and Bessie when I asked where the full text of Stanley’s speech might be in the archives — that the Major had felt the park needed a properly rhetorical christening, and had himself composed the words the pedestal proudly displays as Stanley’s.

Language, in its declarative power, in its ambiguities, nuances, fabrications, is the poet’s toolbox. For poets of my generation, coming of age in the sixties and seventies, it is the particulars of language, just as it is the particulars of the imaginative and material worlds, that make up poetry’s fabric. I knew enough then of what a poem required to sense that what I was picking up in Vancouver Archives was pure gold. I didn’t know well enough how to work it.

Some years later, after a professional year of teacher training, a year of teaching high school in East Vancouver, and a year wandering around Europe and North Africa, I returned to a Vancouver that felt manageable to me, that I could explore and write my way into on my own terms.

In 1975, living on the North Shore with a view over the city that accommodated exactly the distance and perspective I needed, I completed a collection of poems entitled Port of Entry that attempted to blend my personal history with that of the city, to discover the evolving shape of my life in that place.

In several of those poems the Major speaks. In one poem especially, he speaks through the anecdotes above to scraps of history that I’m still pondering. Here’s how that poem came about. Late in my time in the archives, late in that summer of 1969, my girlfriend of the day returned from her family home in southern California to continue her studies at UBC. She and I rented a suite in an old house in Kits, corner of Second Ave and Arbutus, and while I spent those last few late August/early September days clipping newspaper articles and listening to the Major, she was furnishing our first shared abode. She had a small Suzuki dirt-bike and would troll up and down the alleys of Kerrisdale looking for likely articles of furniture the wealthier denizens of the city had thrown out.

We would meet for a picnic lunch somewhere convenient downtown, often on the grassy edges of English Bay just below Beach Ave. at the north end of the Burrard Bridge. One day D. showed up astride a carpet rolled and strapped awkwardly to one flank of her motorcycle. Excitedly she dragged and unrolled her find before me on the grass. It was a heavy weave, faded black with large sombre floral designs in greens and yellows burgeoning from two opposite corners. It wasn’t oriental, too indelicate for that, but a no-nonsense quality shone through its gothic shabbiness, most brightly from its back. We loved it and it was on floors backside up wherever we lived together until we didn’t live together anymore, and on floors in studies or workrooms of mine for many years after that.

We would meet for a picnic lunch somewhere convenient downtown, often on the grassy edges of English Bay just below Beach Ave. at the north end of the Burrard Bridge. One day D. showed up astride a carpet rolled and strapped awkwardly to one flank of her motorcycle. Excitedly she dragged and unrolled her find before me on the grass. It was a heavy weave, faded black with large sombre floral designs in greens and yellows burgeoning from two opposite corners. It wasn’t oriental, too indelicate for that, but a no-nonsense quality shone through its gothic shabbiness, most brightly from its back. We loved it and it was on floors backside up wherever we lived together until we didn’t live together anymore, and on floors in studies or workrooms of mine for many years after that.

That carpet prompted, sometime in the early seventies, this poem, which still speaks to me of the complex, ad hoc, oddly fortuitous ways we make, and make up, our lives, a city, a history in language:

The Carpet

on park grass

between ocean

and the city

rolled out

in a noon-hour

between the history

and the archives

where we will put our feet

on a floor in Kitsilano

rolled out

obvious, the weave

scattered at the edges

the Major’s stories of Vancouver

scattered, anecdotal in his ninety-third year

of the C.P.R., steel stretched to an idea

“red-route around the world”

threads of empire. the city

woven into his fantasy

in his words Lord Stanley

dedicates the park

“To the use and enjoyment of people of all

colours, creeds and customs for all time

I name thee…”

no records remained, no evidence but

the requirement of a history

a carpet, on the forest

floor, to calm the sea

a history to be contrived

to accommodate. somewhere to live

for everyone. inside the language.

Considering the drama portended by the subterfuge surrounding my arrival at Vancouver City Archives, my departure in September 1969 was anti-climactic. I confided to Mary Beveridge that I was planning to return to UBC, into the Faculty of Education. A shortage of teachers in B.C. had prompted the province to reduce student fees that fall for graduates enrolling in a fifth year to pursue a teaching certificate and I had, somewhat despondently, decided to take the bait.

My mother, as usual, had alerted me to the opportunity. She’d been a teacher and was then concluding studies to become a teacher-librarian. The profession was, in the parlance of the time, a meal ticket. And I didn’t have the grades for grad school.

Mrs Beveridge was not surprised at my decision. I realized she may have known all along, or had easily guessed, the true dimensions of my position as archivist in training. She rightly thought I should tell the Major I was leaving, and when I did there was none of the awkwardness or histrionics I’d half expected. Maybe he’d known too; perhaps he’d been using me in his war with city hall just as they had. My role had played itself out to the usual stalemate.

He wished me well. If he seemed a little sad, defeated, it was age that was finally defeating him, not my departure. Though I mistakenly add two years to his age in the poem (he would have been in his ninety-first year that summer) the lifetime he’d spent battling for his version of Vancouver’s history, and a home for it, was coming to an end.

That fall he went into care at the Shaughnessy Hospital for veterans, where he died a year later. Departing that September, the best part (in every sense, I see now) of my twenty-second year concluded, I returned to UBC, into a building distressingly decked out in exuberant kindergarten colours, on my desultory way to becoming an English teacher.

*

John Pass’s poems have appeared in 19 books and chapbooks in Canada, and in magazines in the US, the UK, Ireland, and the Czech Republic. He won the Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 2006 for Stumbling in the Bloom and the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize (BC Book Award) in 2012 for crawlspace. His latest book is Forecast: Selected Early Poems 1970-1990 (Harbour, 2015). Last year “Margined Burying Beetle” from a new sequence, “Creation of the Animals,” won the Malahat Review’s Open Season Award.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

I much appreciated this note about Matthews. I was delighted to find Matthew’s quirky, important notes on “Indigenous place names on Burrard Inlet and Howe Sound” in the City Archives a few years back. They were gathered in the 1930s, published by the Vancouver Museum only in 1948, and “certified correct” by the Squamish Indian Council.

I also found Matthews reminded me of endearing, annoying, terminally eccentric old settler relatives.

Thanks for a great article.

This was a particularly interesting and amusing article to me. My paternal grandparents came to Vancouver, as very young people, with their respective families in 1885 and 1886 (they met and married somewhat later). (My dad moved us to Nanaimo in ’66, when I was 18–so his branch had a full 100 years in the city.) My grandfather experienced the Great Fire. My late father (born 1910) knew Major Matthews as a difficult fellow, who would leave your family’s info. out of the archives if you’d had a difference of opinion with him. When I was listening to those rants about “Old Matthews” in my childhood and youth, I had no idea the man was still alive. I’d assumed he’d been someone even older than my grandparents and must be long deceased.