#74 Street views before Google

January 16th, 2017

REVIEW: Glorious Victorian Homes: 150 Years of Architectural History in British Columbia’s Capital

By Nick Russell

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2016.

$29.95 / 9781771511865

Reviewed by Larry McCann.

*

Nick Russell, in Glorious Victorian Homes, photographs and identifies the architectural styles and provincial importance of 147 of the City of Victoria’s finest and most noteworthy houses. (Of the region’s fourteen municipalities, he looks solely at the City of Victoria.)

Reviewer Larry McCann assesses the considerable practical and historical value of this most welcome book.

*

Glorious Victorian Homes is vintage Nick Russell, written with verve, wit, and deep insights about Victoria’s architectural heritage. Well-known and highly regarded for his volunteerism as a leader in preserving Victoria’s architectural heritage, Russell has deepened our understanding of the houses and builders of the Capital Regional District’s oldest municipality.

Glorious Victorian Homes builds on Russell’s Glorious Victorians: 150 Years, 150 Houses (Old Goat Press, 2011), as well as on the continuously updated and award-winning publication series, This Old House: Victoria’s Heritage Neighbourhoods (Victoria Heritage Foundation, 1979-2014) – a four-volume set that offers historical and contemporary photos and well-researched descriptions of the architecture, architects, builders, and principal early owners of over 900 registered heritage houses in Victoria.

Glorious Victorian Homes builds on Russell’s Glorious Victorians: 150 Years, 150 Houses (Old Goat Press, 2011), as well as on the continuously updated and award-winning publication series, This Old House: Victoria’s Heritage Neighbourhoods (Victoria Heritage Foundation, 1979-2014) – a four-volume set that offers historical and contemporary photos and well-researched descriptions of the architecture, architects, builders, and principal early owners of over 900 registered heritage houses in Victoria.

Russell also had a hand in the recent award-winning website of the Victoria Heritage Foundation, an on-line, interactive GIS (Geographical Information System), which allows individual houses in the four volumes to be explored within their wider neighbourhood context and which complements this fine effort.

The Foundation’s four volumes were produced for the City of Victoria. Working with a team of knowledgeable experts, including William Muir and Jennifer Nell Barr, and funded by all levels of government, Russell contributed greatly to the success of This Old House as researcher, writer, and Production Editor.

As he wryly acknowledges in Glorious Victorian Homes, “I have tried hard not to rely on This Old House for the background on the houses, preferring to do my own research. But if readers occasionally encounter a similarity in a house description here to This Old House, that may be because I wrote many of those descriptions in This Old House!”

In Glorious Victorian Homes, Russell sets to work after a brief introduction that establishes the book’s purpose and context. He comments on a carefully selected group of what he justly considers glorious case study houses and backs up his choice with the polished skills of photographic and documentary analysis.

The book comprises a succession of carefully wrought photographs by Russell and pithy descriptions of individual houses, their architectural features, and the interesting people who made them their homes. This includes commentary on both the material and social elements that distinguish what Russell calls these “Victorian (play-on-words) Homes” of the capital city.

Russell’s playful use of language is carried forward cleverly in the pleasing design of the book: the essential colour motif appearing throughout is purple. Surely not by chance, but never mentioned, Queen Victoria wore a purple dress to the Great London Exposition in 1862, the very year that Victoria was incorporated as a city!

Russell is a skilled photographer. Each of the 147 houses is photographed from a street-view perspective. For some of these single-family residences, Russell provides close-ups of prominent architectural elements — brackets, chimneys, dormers, finials, porch columns, shingles types, windows of all shapes, and other details. A useful glossary defines these and most other mentioned architectural elements.

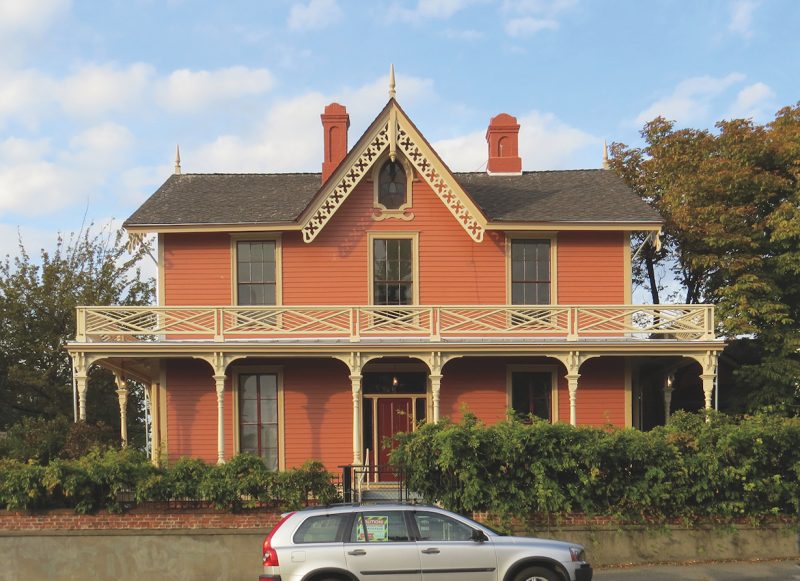

An example of Gothic Revival, this Wentworth Villa, built in 1863, was recently-restored to become an architectural heritage museum.

Judging by the frequency of their appearance, Russell finds finials, those vertical elements emphasizing the peak of a roof, especially enchanting. He also provides a valuable reference graph of Victoria’s year-by-year building history. He references all of the featured houses by street name and house number and locates them on a city map at the close of the book, a useful aid to those architectural buffs who go in search of their personally identified, must-see houses.

Occasionally, a map of a street or an image of a streetscape is introduced in the text, but more of these would have been useful in establishing the wider spatial and social context of Russell’s chosen houses and homes.

A reader familiar with the work of the Victoria Heritage Foundation might also wonder why no reference is made to the Foundation’s recently created on-line GIS (Geographical Information System), which offers an easily-accessible way for readers to benefit from this authoritative analysis. Viewers who zoom in, via aerial photography and street-view tools, will discover that Victoria’s residential neighbourhoods are notably diverse in their architectural styles, with most streets displaying houses built in different building eras stretching from the late-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth.

This eclectic pattern is a hallmark of the Greater Victoria region which, on the eve of the First World War, boasted well over 300,000 building lots for a population of some 30,000 people. The need to fill these many vacant lots would bedevil policy makers in the City of Victoria and suburban municipalities through to the mid-twentieth century.

The unexpected result for Victoria’s early neighbourhoods is a rich and pleasing variety of housing styles. This situation is quite unlike larger Canadian cities where many, if not most, nineteenth and early-twentieth century subdivisions were built-out in a very short period of time, with the result that they typically display few contrasting architectural styles.

An analysis of houses in their wider and often heterogeneous streetscapes can add appreciably to our understanding of how a house fits into a city’s architectural landscape.

To detail his version of Victoria’s architectural history, Russell unfolds his historical chronicle by identifying a dozen established and easily recognized styles or categories.

These form short chapters that include well-honed, period-specific titles such as “Early Vernacular & Homestead,” “Gothic Revival,” “Tudor Revival,” and “Art Deco & Art Moderne.”

The use of these terms suggests that the citizens of Victoria were largely intent on adopting examples of universal building styles, perhaps by selecting an appealing dwelling from a pattern book of house plans, or by asking their builder or architect to copy a house seen elsewhere — just as we do today.

Russell does not pursue this broader line of analysis here; it was not his purpose, nor should it have been for this venture. But some day, I hope, as do others, that he will turn his attention to this and other themes of Victoria’s architectural history that need telling, such as changing building technologies, the interior arrangement and use of rooms, the factors causing the shift from one fashionable style to another, or the links between the migration of different socio-ethnic groups to Victoria and the resulting localized adoption or adaptation of particular architectural styles.

Victoria is a place that some architectural historians have called a “British Imperial Outpost.” Or does Victoria’s architectural history owe more to cultural ties with its southern neighbour, the United States? Now that Russell and his colleagues have assembled an invaluable database of Victoria’s heritage houses for further study, the opportunity exists to delve into broader questions and themes that mark the architectural heritage of the city.

Besides his considerable skills as researcher and photographer, Russell’s informed, original, and succinct discussion of a selection of Samuel Maclure’s renowned architectural contributions to Victoria’s landscape, sometimes dramatically in the Tudor Revival style, suggests that he is exceptionally well-equipped to advance this task, or at least to offer tutelage to the next generation of architectural historians.

The Hankins’ House was designed by Samuel Maclure and built for $10,000 in 1911. It exemplifies the Tudor Revival style.

Russell is equally well positioned, by virtue of a keen and roving eye, to assess the architectural gems of the older adjacent suburbs that make up metropolitan Victoria, such as Oak Bay, Saanich, and Esquimalt. Let us hope that he turns to these next.

Russell adds a certain beguiling charm to the standard classification scheme with some captivating groupings, for instance with sections on “Passing Fancies,” “Glorious Eccentrics,” and “Brick Beauties.” Here we see the witty Russell at his best.

In “Passing Fancies,” he points out that for Victoria’s homeowners, some popular North American architectural styles failed to “catch the public imagination.” These include the Georgian, Mansard, Mission, and Shingle styles, all of which found preference elsewhere, whether in cultural hearth areas or peripheral regions — but not in Victoria. One wonders why?

At the same time, as revealed in the section “Glorious Eccentrics,” Russell brings irreplaceable houses by gifted architects like Francis Rattenbury to the fore, adding depth and divergence to the overall pattern.

Russell’s “Eccentrics” speak to his ability to separate the “wheat from chaff” in the city’s architectural landscape, giving the reader confidence in his overall selection of case-study houses.

And this is the overarching strength, the considerable merit of Glorious Victorian Homes: to provide a carefully rendered guidepost and introduction, compiled and written by a knowledgeable and talented writer, to the City of Victoria’s architectural heritage.

Russell’s scope is suitably wide-ranging. He draws attention to some of the City’s oldest colonial houses and recognizes, as well, mid-twentieth century modernist dwellings. He makes a gentle, realistic plea to preserve this built heritage.

Through his own personal efforts at restoration, by his volunteerism, and by sharing his considerable research on Victoria’s architectural past in this excellent book, Nick Russell has created a solid base to spur on both public interest and scholarly analysis of the architectural history of that most glorious and Victorian of places, British Columbia’s capital city.

*

A native Victorian, Larry McCann is a historical geographer affiliated with the University of Victoria. He is the former Davidson Professor and Director of the Centre for Canadian Studies at Mt. Allison University in New Brunswick, where he guided its national publication program. He has published many articles and book chapters and written or edited ten books, including Heartland and Hinterland: A Geography of Canada (3rd edition, Prentice-Hall, 1998) and Imagining Uplands (Brighton Press, 2016). He has served on various national and international committees such as the National Capital Planning Commission (Ottawa) and the Advisory Council of the National Association of Olmsted Parks (USA). For his various research and professional contributions, he was awarded the Massey Medal from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. He is also a recipient of awards from the Association for Canadian Studies, The British Columbia Heritage Society, CMHC, the Hallmark Heritage Society of Victoria, and the Killam Foundation; and a teaching award from the University of Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply