#228 Reconciliation dances & divides

December 23rd, 2017

Residential Schools and Reconciliation: Canada Confronts its History

by J.R. (Jim) Miller

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

$39.95 / 9781487502188

Reviewed by Andrew Woolford

*

Reviewer Andrew Woolford praises Jim Miller in Residential Schools and Reconciliation: Canada Confronts its History for providing a thorough institutional history and much detail of Indigenous-settler relations — but claims, “Voices from various counterpublics, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, that critique the politics of reconciliation are seldom found in Residential Schools and Reconciliation.”

Reviewer Andrew Woolford praises Jim Miller in Residential Schools and Reconciliation: Canada Confronts its History for providing a thorough institutional history and much detail of Indigenous-settler relations — but claims, “Voices from various counterpublics, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, that critique the politics of reconciliation are seldom found in Residential Schools and Reconciliation.”

Everyone on the spectrum has a different stance, a different dance.

Woolford asserts we are “very fortunate to have a book such as J.R. Miller’s Residential Schools and Reconciliation,” but, according to Woolford’s viewpoint, Miller provides a comfortable “settler mainstream” narrative that makes it difficult to “unsettle Canada.” Woolford alleges that Miller relies on memories from inside governing institutions; privileges experts “who hold prominent political, social, or legal positions;” provides an artificially balanced account of the “good and the bad” of residential schools; and shows a narrow understanding of genocide law.

Reconciliation, Woolford argues, “will be a much more unsettling process than the journey Miller takes us on. It will require not only engagement with Indigenous views as presented by Indigenous political leaders and prominent Survivors; it will also require consideration of those Indigenous perspectives that push beyond the political status quo.”

Anyone who speaks up invariably risks being criticized for upholding narrow views, no matter who well-intended their desire to speak may be.

Welcome to the Reconciliation debate. – Ed.

*

Projects of justice and reconciliation in a national context are never straightforward affairs. Governments do not wake up one day and decide to deal with the nation’s past wrongs. These processes are slow-forming and marked by moments of both conflict and cooperation.

When one thinks, for instance, of post-Second World War reparations in Germany, the varied approaches to compensation, restitution, commemoration, and criminal adjudication took decades to emerge, and they did not do so in a linear fashion.

West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer certainly believed that Germans had a moral responsibility to contend with the wrongs of the Holocaust, but reparations needed to be negotiated carefully within his own party, with his opposition, and with the electorate, not to mention Jewish Survivor groups, the emerging state of Israel, and the Allied powers. Even once the initial negotiations were completed, the process would reopen on several occasions, as groups left out of the reparations policy, such as Jewish people targeted outside of German borders or the Roma and Sinti, would pursue political and legal action to have their suffering acknowledged.

Reparative processes are complex. We are therefore very fortunate to have a book such as J.R. Miller’s Residential Schools and Reconciliation, which provides a thorough institutional history of the emergence of reconciliation for Canada’s residential schooling past, with particular attention to the development of the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement (2007, hereafter IRSSA). Miller traces this story from early efforts to challenge the Canadian myth of benevolence, which arose around Survivor revelations of their experiences, particularly in the 1980s. This too-often ignored testimony was vindicated in the sections of the 1996 report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (RCAP), which recorded the destructive impact of the IRS system.

Miller also covers various church apologies, the Canadian government’s statement of regret, the formation of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, the initial lawsuits and class-action cases, and the efforts to create an “alternate dispute resolution” process to expedite these court challenges. Through all of these events, Miller brings the reader to the IRSSA, including its compensation (Common Experience Payment and Independent Assessment Process), commemoration, and commission (the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada) components.

Drawing on the considerable archive of documents related to all of these process, as well as interviews with many key players at each stage of the process, Miller presents a fairly comprehensive overview of how we have come to our current stage of Indigenous-settler relations, a stage at which Miller, though not blind to the challenges, sees some promise for reconciliation.

The handling of the history of the negotiations that led to various stages along Canada’s path to its current process of reconciliation is deft. Through Miller’s narrative, one gains a sense of the tensions faced by various primary actors in seeking to find a viable solution. I especially appreciated Miller’s coverage of the negotiations that took place between the demise of dispute resolution and the creation of the IRSSA (Chapter 5).

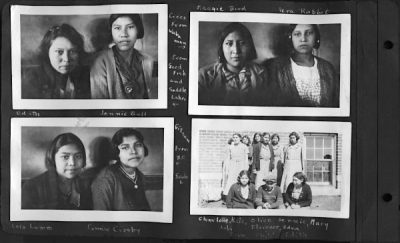

Edmonton Indian Residential School, circa 1940. Destroyed by arson, 2000. United Church of Canada Archives.

In 2004, the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) criticized the dispute resolution process for, among other concerns, too narrowly focusing on physical and sexual abuse, and ignoring cultural harms (pp. 131-32). In Miller’s telling, the AFN critique, alongside their proposal of a lump sum compensation plan, combined with the certification of class action law suits, such as Cloud and Baxter, to create the necessary conditions for a new approach to IRS to be sought. These broader political openings were the context for conversations, such as the one between Phil Fontaine and then Prime Minister Paul Martin when attending the funeral in Rome for Pope John Paul II, that intensified the momentum toward the IRSSA.

It is when providing such texture that Miller’s institutional history is most effective, giving one an almost insider view of how events transpired.

On the flipside, the story Miller tells is a comfortable story. It is one that seeks balance, to show how the process of reconciliation unfolded in a manner that is objective and clear, while remaining distant from what Miller might feel are more extreme views.

But one might wonder whether we can unsettle Canada through such comfortable narratives. Miller suggests that RCAP brought a more “radical” understanding of Canadian history to the table, but he stops short in exploring how far this critique has come. This may be, in part, a result of whom he chooses to interview and the authors he selects to read.

His list of interviewees features many people who have firsthand knowledge; several were there at the centres of power and witnessed how the reconciliation process came to pass. Their memories are taken as reflecting the “truth” of the process, rather than interrogated to show what visions of justice and reconciliation they privilege.

This is not a history from the margins, nor are those margins fully recognized. Voices from various counterpublics, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, that critique the politics of reconciliation are seldom found in Residential Schools and Reconciliation. On occasion, such critical voices are gleaned from other sources — Survivors’ voices, for example, aside from those of six of his 48 interviews (most of whom are also Indigenous leaders), are predominantly drawn from reports produced by entities such as the Assembly of First Nations, who conducted research on Survivor reactions to IRSSA compensation schemes.

Not only are these voices already curated by other authors, they generally represent “experience” rather than expertise in Miller’s usage. The experts remain those who hold prominent political, social, or legal positions.

As with Ronald Niezen’s Truth and Indignation (University of Toronto Press, second edition, 2017), Residential School and Reconciliation even questions the expertise of Survivors by suggesting that there may have been some pressure on them to frame their trauma in a negative fashion (p. 233). But the fact that Survivors rely on common themes and tropes in recounting their trauma should not be used to discount the truth captured within their testimony. Trauma involves a complex of experiences and feelings that is difficult to contain in a traditional narrative. For this reason, Survivors quite often rely on resonant frames or scripts to help make their pain communicable.

That negative stories frequently arose and took similar shape in the context of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission does not mean that a negative interpretation of the past was imposed; it simply means that Survivors sought to communicate their trauma through themes and imagery that would be recognizable to listeners.

Miller seems to rely primarily on statements made at public events, since he does not appear to have access to the individual statements gathered by the TRC, meaning that the speakers were addressing and hoping to be understood by a diverse audience.

Added to this point, which speaks to Miller’s concern that only the negative story of IRS is being told, whatever more “positive” intentions teachers and other staff may have had at Indian Residential Schools, it should come as no surprise that an institution borne of a violent impulse to tear Indigenous children from families and cultures produced primarily “negative” remembrances. Unsettling Canadian history is not served by an artificially balanced account of the “good and the bad” of residential schools.

It is also telling that Miller speaks to none of the critics of the dominant discourse of reconciliation, such as powerful Indigenous scholars like Taiaike Alfred, Leanne Betasmoke Simpson, Glen Coulthard, and Pamela Palmater. The work of these scholars does not even make it into his bibliography. For the most part, memories from inside governing institutions, or from mainstream Canadian history, are prioritized as the definitive story of Canadian reconciliation.

These other voices on reconciliation, however, also have an important story to tell about the prospects for unsettling Canada. Miller discusses the unlikelihood of reconciliation being achieved without the “cow” of territory being discussed, referencing a story lawyer Kathleen Mahoney told about the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where an episode of apology and forgiveness was followed up by the wronged party asking, “now what about that cow you stole?” (p. 269).

Indigenous scholars, such as those named above, have produced some of the most insightful scholarship on this very question and its importance to future decolonization. Without benefit of their insights, Miller’s analysis stops short, leaving territory as a property right to be restored to Indigenous peoples rather than as something constitutive of their existence as groups. Most perplexing is the quotation from John Crosbie that opens the book, that discusses the need “to reconcile them [Indigenous peoples] as part of the Canadian mainstream and to deal with their problems” (p. 1). This appears to frame the book in the language of the Indian problem rather than the settler problem. Critical Indigenous scholarship would have helped Miller see that this is a troubling frame for his book.

Miller further shows his commitment to a comfortable mainstream when discussing Indigenous group destruction through the IRS system. He appears somewhat put off by the question of genocide, thinking that those who raise the issue in relation to Indian Residential Schools are being hasty, if not irresponsible. He notes that the United Nations Genocide Convention covers destruction of a “national, ethnical, racial or religious group” and mentions section 2(e) of the convention, which refers to destruction through the “transfer of children of the group to another group.”

But then he reasons that this is difficult to apply because “only about one-third of status Indian children, and a smaller fraction of Métis children,” attended IRS. He queries: “Can such a social experiment be described as transferring a racial … group to another people when so many others were not targeted?” (257).

This statement is problematic on legal grounds, since it ignores the condition that a group is destroyed “in whole or in part,” the fact that genocide law always speaks to the “attempt” rather than the outcome, and that genocide case law has moved beyond the antiquated notion that there are “racial” groups to be destroyed, or that any of the target group categories can be defined in solely objective rather than subjective terms (that is, in terms of how perpetrators and victims understand these groups).

More challenging in the Canadian context, though, is the fact that Miller treats Indigenous peoples as a single group. The genocide concept was created by Raphael Lemkin to protect what he saw as distinct culture-bearing groups or “nations.” Miller has clearly selected the wrong unit of analysis, since it is the individual Indigenous cultures rather than a homogenized Indian that is of concern when discussing genocide.

As well, Miller fails to recognize that, despite its legal status, genocide remains a contested notion, meaning that there are usages of the term beyond its legal meaning. There is good reason for this. Like any law, genocide is a political creation, it has a history, and much was removed from the UNGC when Lemkin brought his concept to the UN General Assembly.

For Canadian purposes, of particular importance is the removal of practices of “cultural genocide” from the UNGC. Part of the rationale for nations supporting the removal of the section Lemkin had drafted on cultural genocide was that certain peoples were too “primitive” or “barbaric” to deserve such protection, as one can see when reading the Travaux Préparatoires, the working papers, for the Convention.

In this sense, genocide law is infused with the very same “frontier” mentality that Miller correctly acknowledges is problematic in the histories of Frederick Jackson Turner and George Stanley (p. 265). Miller worries that genocide is divisive, but how is it not more divisive to ignore the colonial foundations of law, or to fail to recognize the importance of cultural preservation to the protection of Indigenous groups as groups?

I learned a great deal from reading Residential Schools and Reconciliation. Like Miller’s previous books, it provides much detail of Indigenous-settler relations and the institutional practices that have characterized these relations. However, though Miller promises to show how “historical understanding has evolved and how Canadians have come to grips with the negative aspects of their country’s past,” as well as “how Aboriginal people in Canada have responded” (p. 6), he is mostly showing a settler mainstream representation of this understanding and response.

Reconciliation, never fully defined or discussed in terms of what it means in Miller’s book, will be a much more unsettling process than the journey Miller takes us on. It will require not only engagement with Indigenous views as presented by Indigenous political leaders and prominent Survivors; it will also require consideration of those Indigenous perspectives that push beyond the political status quo.

*

Andrew Woolford is professor of sociology at the University of Manitoba. He is former president (2015-2017) of the International Association of Genocide Scholars. He is author of ‘This Benevolent Experiment’: Indigenous Boarding Schools, Genocide and Redress in the United States and Canada (University of Manitoba Press, 2015), The Politics of Restorative Justice (Fernwood Publishing, 2009), and Between Justice and Certainty: Treaty-Making in British Columbia (UBC Press, 2005), as well as co-author of Informal Reckonings: Conflict Resolution in Mediation, Restorative Justice, and Reparations (Routledge, 2005). He is co-editor of Canada and Colonial Genocide (Routledge, 2017), The Idea of a Human Rights Museum (University of Manitoba Press, 2015), and Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America (Duke University Press, 2014). Dr. Woolford is currently working on two community-based research projects with residential school Survivors: “Embodying Empathy,” which will design, build, and test a virtual Indian Residential School to serve as a site of historical knowledge mobilization and empathy formation; and “Remembering Assiniboia,” which focuses on commemorative activities for the Assiniboia Residential School in Winnipeg. He is a Fulbright Scholar and Member of the College of the Royal Society of Canada.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply