#328 Meggs revisits1900-1901 strike

June 24th, 2018

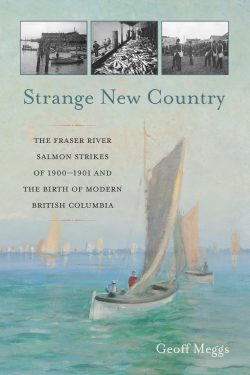

Strange New Country: The Fraser River Salmon Strikes of 1900-1901 and the Birth of Modern British Columbia

by Geoff Meggs

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018.

$22.95 / 9781550178296

Reviewed by Howard Stewart

*

A fascinating window into the early decades of resettlement on the Strait of Georgia, Geoff Meggs’s Strange New Country: The Fraser River Salmon Strikes of 1900-1901 and the Birth of Modern British Columbia is launched with an apt reference to a bilingual Chinook-English poem, Terry Glavin’s “Rain Language:” “Everyone was thrown together to make this strange new country.”

A fascinating window into the early decades of resettlement on the Strait of Georgia, Geoff Meggs’s Strange New Country: The Fraser River Salmon Strikes of 1900-1901 and the Birth of Modern British Columbia is launched with an apt reference to a bilingual Chinook-English poem, Terry Glavin’s “Rain Language:” “Everyone was thrown together to make this strange new country.”

Meggs provides a highly readable account of the strikes organised by salmon fishers at the mouth of the Fraser River just after the turn of the twentieth century and a compelling case study of what happened when locals and newcomers from around the world were thrown together in this strange and scandalously well-endowed new country now named British Columbia.

Strange New Country doesn’t understate the complexity of relations among the Indigenous, Japanese, and European fishers who comprised the province’s early industrial fishery. Partly for this reason, I found this a better read than Meggs’s earlier prize-winning history of the coastal salmon fishery, Salmon: The Decline of the British Columbia Fishery (Douglas & McIntyre, 1991).

As much as I enjoyed Salmon, Meggs tended to oversimplify this complex fishery, attributing too many events — with not always plausible assurances – to the virtues of the fishers and the villainy of the canners. This may have been de rigueur for someone who had worked for the fishermen’s unions, and there was undoubtedly considerable truth to it, but it was an oversimplification nonetheless that diminished the book’s credibility as a balanced source for my own research into the environmental history of the Salish Sea.

Strange New Country is more nuanced and therefore, for me, a more satisfying story. The canners are still mostly one-dimensional villains, especially their leader Henry Bell-Irving of the Anglo-British Columbia Packing Company. But the working class heroes are more complete and fascinating personalities. Meggs brings all three of them — Indigenous fishers’ de facto leader George Kelly, Japanese fishers’ leader Yasushi Yamazaki, and Frank Rogers, leader of the BC Fishermen’s Union – to life as complex characters emerging from dynamic and fast-changing communities that were usually at odds with the other two.

Meggs’s engaging sketches of these labour leaders and their respective communities are a great strength of the book. They give the reader a vivid and clear sense of the huge challenges confronting these leaders as they tried to present a unified front in the face of a far more homogenous opposition composed of hard-nosed Anglo-Canadian frontier businessmen used to having their way.

This episode in early B.C. labour history illustrates those times perfectly. Meggs’s colourful description (p. 15) of the seasonal fishing and canning boomtown of Steveston on the Fraser’s South Arm could describe all of B.C. in 1900: “[A] place of opportunity where legal authority was weak, the power structure was clear and there was money to be made….”

The fishermen were united, Meggs tells us, by their grim determination to wrest a decent living from a scandalously rich fishery that had made the fortunes of canners like Bell-Irving. Yet the fishermen were at least as divided by what Meggs calls “social pressures.” After half a century of formal colonisation, Indigenous fishers were fighting a rear guard action. Having lost control of most of their traditional fishing grounds, they now struggled to retain their already diminished role as paid fishers for the canneries, particularly in the face of rapidly growing numbers of Japanese immigrants.

The Nikkei fishers, mostly recent arrivals from a Japanese homeland in the throes of its own tumultuous modernisation, were struggling to escape poverty. They were desperate to establish a foothold and put down roots in a new land, despite the intense racism of the white majority and the deepening animosity of Indigenous competitors.

Finally, the “White” fishermen were themselves wrapped up in the intense class struggle of turn-of-the-century British Columbia. They were determined to assert their own right to benefit from an apparently infinite resource bounty and to fight back against a moneyed elite who controlled everything in the young province, including this almost unimaginably rich fishery.

That is to say, all three groups of fishers had very different agendas, which made it a minor miracle that they could unite, albeit briefly, in their struggle to get a decent price for the Sockeye and Pink salmon they were hauling in by millions — and by millions more in the “big years” where the Fraser spilled abundantly into the Strait of Georgia.

While I greatly admired this book, sometimes I found it almost too nuanced. A sign of my advancing age perhaps? I had to strain to remember the grim history of discrimination by the white majority against all other races that would only begin to diminish a half century after this strike. Meggs does not elide this unhappy dimension of our history, but he does tend to downplay it, opting instead to celebrate the salmon strikes of 1900-1901 as a happy precedent, demonstrating what was possible when racial barriers dividing workers were transcended.

In its details a remarkably confused and confusing affair, the salmon fishers’ strike briefly brought together protagonists with little natural inclination to cooperate. Inevitably, it’s sometimes difficult to ascertain exactly what was happening, who was doing what, and what was the result. While Meggs has done a fine job of unravelling this tangled matrix of players and events, I believe he may overstate the lasting effect of this moment of labour cooperation across racial lines. One could just as easily bemoan the fact that subsequently it took some five decades to recover the momentum of this short-lived success.

Meggs concludes that a rich, powerful, and highly lucrative resource industry remained successful in dividing anyone who dared to stand in its way. In B.C. and Alberta we are once again in the throes of a similar crisis as we grapple with the Kinder Morgan pipeline.

*

Howard Macdonald Stewart is author of Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of Georgia (Harbour Publishing, 2017). An historical geographer and semi-retired international consultant whose work has taken him to more than seventy countries since the 1970s, Howard has reviewed books for The Ormsby Review and BC Studies. His 17,000- word story of a 1973 bicycle trip down the Danube with the war hero and debonair cyclist Cornelius Burke was published by The Ormsby Review (September 28, 2016), and he is now writing an insider’s view of his four decades on the road, notionally titled Around the World on Someone Else’s Dime: Confessions of an International Worker. He has lived on Denman Island, off and on, for more than thirty years.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of

B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory

Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis,

Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly

Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of

September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply