#329 From inuksuit to cyberspace

June 26th, 2018

Sculpture in Canada: A History

by Maria Tippett

Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2017

$39.95 / 9781771620932

Reviewed by Catherine Nutting

*

Maria Tippett’s Sculpture in Canada is, she writes, not an encyclopedia, but an introduction; an eye-opener to some of the greatest Canadian sculpture. The book is an ambitious project. It covers material from c. 20,000 BCE up to the 21st century, with the aim of discussing the sociocultural conditions in which Canadian sculpture has been produced.

Right at the outset, the author begins to define sculpture, a task that she will return to and complicate throughout the book. Chapter 1 is largely concerned with early First Nations sculpture, and Tippett includes shards, tools, and inuksuits. These, as well as powerful house posts, masks, and smaller-scale carvings were traded and sold from coast to coast. There is also interesting mention of early cultural exchange, of apprenticeships involving Canadian and foreign sculptors, and of European Baroque/Rococo artistic trends operating in Quebec wood and marble ecclesiastical carving.

Chapter 2 begins just before the turn of the century, in the late 1800s, and outlines sculptors’ biographies. A large section on commemorative sculpture, it also discusses the history of urban development, patronage, materials, and the influx of Europeans and related art movements such as Symbolism.

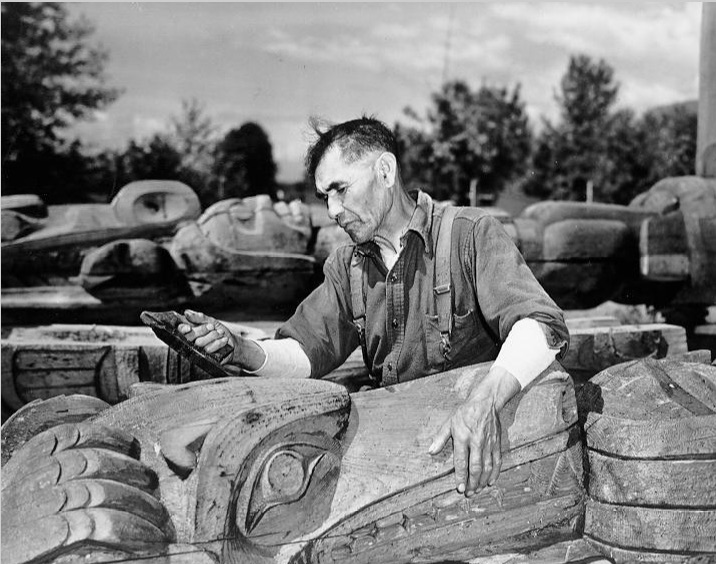

These themes are continued and debated in the next chapter, “At Home and Abroad.” Contact between European and Canadian artists occurred in unexpected ways. For example, Charles Edenshaw innovatively modified images from the Illustrated London News. One interesting theme is the question of influence and of lineages of teachers and students, be they Auguste Rodin, Gustave Courbet, and the Canadian sculptor Alfred Laliberté; or such greats as Mungo Martin, Willie Seaweed, and Ellen Neil.

Chapter 4 discusses sculpture that responded to Canada’s service in World War One. Tippett connects Canadians’ mourning with the business of producing memorial sculptures and an increase in “patriotically” spending money on Canadian art. She argues that it was war commissions that rendered sculpture ubiquitous in the small towns of Canada.

In Chapter 5, Tippett returns to the question of whether there was an unbroken tradition in sculpture from ancient times, through European artists such as Henry Moore, and into modern Canadian sculpture in the work of, for example, Beatrice Lennie, Violet Gillet, and Elizabeth Wyn Wood. The prevalent connection of Canadian wartime sculpture with Italian masters continued, while ground-breaking European modernist work produced creative waves when it was exhibited in Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa. Tippett singles out the important 1920s exhibitions Contemporary Russian Art, International Exhibition of Modern Art, and Selected Groups of Modern European Sculpture (p. 111).

It was a time of fascinating and complicated cultural exchanges. Willie Seaweed portrayed George V in a memorial pole upon the king’s death. The province of Quebec commissioned Alfred Laliberté to depict rural habitants, but then accepted only half the completed sculptures. And Mungo Martin carried out official commissions for totem poles many years before the ban on potlatch materials was lifted.

Arguing that there was little that was both new and good in Canadian sculpture during World War Two, partly because of the scarcity of materials, Tippett’s history jumps to the two decades following the war, where suddenly, she writes, “sculpture seemed to be everywhere” (p. 137). In “Off the Plinth,” Tippett explains how sculpture took off, largely due to generous public funding. Sculptors moved to urban centres, newspapers and journals promoted the public’s understanding of modern sculpture and, as had occurred after World War One, the building boom symbiotically benefitted both architects and sculptors.

There was a convergence of powerful patrons and conflicting tastes. For example, when John Nugent was commissioned to sculpt a commemorative sculpture of Louis Riel, his first response was in the style of Vladimir Tatlin’s 1919 Constructivist Monument to the Third International. When this met with disfavour, Nugent created a realist-expressionist rendering of Riel, only to be made to understand that the bronze figure would require a bronze cape to cover it.

After discussing painters who turned to sculpture, the influence of important European sculptors, and the creative community around the Emma Lake workshops and their visiting instructors, Tippett turns to “Centennial Sculpture.” Regional variations in sculptural output were vast, with Toronto boasting the most commercial galleries for modern art, and Montreal remaining a shining example of creativity, exhibitions, and art-political engagement.

Expo ’67 in Montreal and the concurrent Sculpture ’67 in Toronto demonstrated the importance of sculpture within modernist art. Sculptures from sixty-two nations were shown in Montreal, including works by Michelangelo, Henry Moore, Alexander Archipenko, and the Canadians Louis Archambault, Armand Vaillancourt, Sorel Etrog, Henry Hunt, and Bill Reid, among many others. So much sculpture graced Expo ’67 that Time magazine noted that the area was like “one long contemporary art gallery” (p. 171).

Of particular interest, Tippett raises the problem of how best to present and contextualize contemporary art, including First Nations sculpture; that is, through politics or through aesthetics, a question that Buffy Sainte-Marie addressed at the time. One art historian has recently noted that the modern art and sculpture displayed at Expo ’67 could seem nationally neutral, and so provide an international “common ground” that supported humanist modernist optimism. The connection of modernism with Inuit carving is one of the many reasons Tippett credits for the success of Inuit art in the post-war era, in her long section on the subject.

The final chapter ranges from the late 1960s to the present. Here Tippett discusses art in cyberspace, the historical influences on contemporary work, and the capacity of sculpture to break down cultural barriers. She relates contemporary Canadian sculptural practices to the post-modernist projects of parody, play, and the removal of “high art” from its perceived pedestal. Inherent in many art movements throughout history is a striving for the new, and for this, post-modernists drew on Marshall McLuhan’s, Roland Barthes’s, and Michel Foucault’s theories of popular culture, electronic media, and the contingency of the reader/viewer.

Diverse methods in contemporary sculpture include both highlighting and transcending mediums, and illustrating impermanence through works in progress and found objects, as is evident in the oeuvres of Jana Sterbak, Manasie Akpaliapik, Brian Jungen, or N.E. Thing Co., among many others.

These methods combine with social consciousness in, for example, the work of Melvin Charney, who in 1976 constructed replica façades of historic architecture and positioned them in Rue Sherbrooke, where the original stone heritage buildings had been demolished.

Some of the photos in the book stand out. For example, Poles and Houses at the Haida Village [at UBC], carved by Bill Reid and Douglas Cranmer, 1959-1962, is beautifully photographed, with the setting sun burnishing the beams and the house siding into gold tones that meld perfectly with the finely detailed wood and paint (p. 166). I would have appreciated information on who photographed the images in the book. In addition, information on the sizes of the original objects would have been a welcome addition to the written descriptions. In a similar vein, Tippett’s goal that the book provide a foundation for further research would have been enhanced through the inclusion of more citations and a generous bibliography.

Tippett’s aim was to heighten appreciation for the wealth of Canadian sculpture of which many readers may be unaware. She achieves this through her discussion of many important Canadian sculptors, their work, and their times. The zest of her opinions inflects the crucial historical socio-economic and political details that readers will find intriguing.

*

Catherine Nutting is an art historian whose interests range from interculturalism to philosophy, theory, and contextual historicism, among many other topics. She teaches at the Vancouver Island School of Art and the University of Victoria in World Arts, Modern Art, Renaissance, Baroque, Popular Culture, Canadian Art, and other Fine Arts courses. At present she is researching Early Modern networks of knowledge, and is enjoying teaching the Art History survey at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. She is also a visual artist who works in acrylic and watercolour painting, paper collage, and word/image explorations, many of which draw inspiration from the natural world.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher/Designer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of

B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory

Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis,

Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly

Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of

September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: CreativeBC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Coeur de Lion MacCarthy, The Angel of Victory, 1922. At Waterfront Station, Vancouver. Dave Nunuk photo.

Leave a Reply