#142 Sacred Herb & Devil’s Weed

June 23rd, 2017

Marijuana can be dangerous and joyous. Anyone telling you marijuana is one thing, and not the other, is a liar.

And, yes, it can also be medicinal for some. Much like alcohol, except the death rate and social costs have been far less.

You don’t have to read a government study to figure this stuff out. And don’t trust pot proponents or your neighbour Brad to give you the lowdown.

The truth, my friend, is brilliantly provided in Andrew Struthers’ hilarious, dualistic, ying/yangish, James Joycean, expert compilation of two manuscripts sleeping in the same bed, The Sacred Herb / The Devil’s Weed (New Star $19) reviewed here by Erika Dyck. — Ed.

*

The Sacred Herb / The Devil’s Weed

The Sacred Herb / The Devil’s Weed

by Andrew Struthers

Vancouver: New Star, 2017.

$19 / 9781554201150

Reviewed by Erika Dyck

*

British Columbia is the perfect setting for this timely book on pot. Canadians have come to revere the infamous B.C. bud, and we Canadians living east of the Rockies have often looked west for guidance on how to handle marijuana, whether it be for securing clandestine growing conditions for achieving higher THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) levels, or for government-regulated head shops set up in broad daylight in Kitsilano.

B.C has long had a reputation for its green culture, and Canadians have come to expect leadership from beautiful B.C.

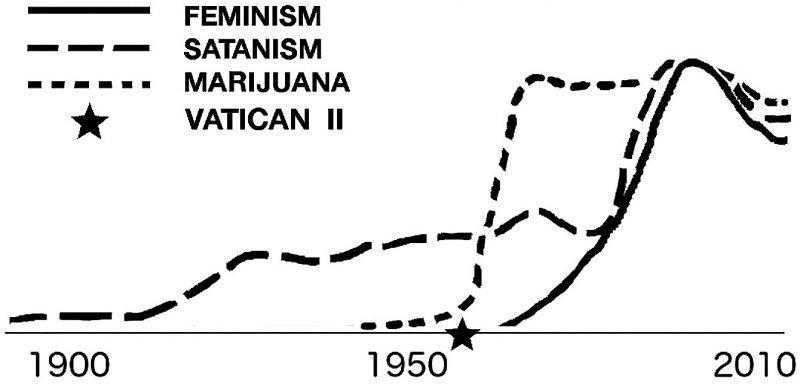

Struthers taps into that characterization, but does so in a rather unorthodox manner. The book is cleverly designed to portray different sides of a debate on marijuana, or so it appears at first glance. The provocative alternate titles and cute marketing design set up my expectations as a book that might delve into the pros and cons of marijuana use. But that debate is hazy and vague, and not really a debate at all, in this two-sided text.

I began with The Sacred Herb, for no particular reason, except that as a historian of drugs, I erroneously felt that I was well versed in many of the critiques of drug use and wanted to start by reading about why it might be indeed Sacred, or mystical, and an — or a — Herb, expecting some discussion of it being natural, or organic.

But I was wrong. This section of the book is a more in-depth account of a journey through research, anecdote, and personal experience as Struthers unpacks common assumptions and myths about marijuana. He rarely pauses to deeply consider the contemporary debates in regulation, or in clinical studies, but begins from the perspective of a devoted user, grower, and liberal thinker on the matter.

Far from an academic account, his lucid and often entertaining analysis pokes fun at some of these larger debates. He deftly casts aside policy issues but shows individuals’ stories to expose how loosely the laws have been applied, or how hypocritical our regulations are when it comes to allowing for public drunkenness while prohibiting weed.

In sum, he gives readers a highly engaging and amusing description of the long-standing contradictions in our cultural, medical, and political understandings of the dangers of marijuana use. At moments, this section reads like a Cross-Country check up for marijuana users, covering Canadians from Newfoundland to British Columbia in their quest for bud, whether it be to grow, smoke, sell, or talk about.

The Sacred Herb is highly readable, witty, and engaging. It shifts from intellectual provocation to laugh-out-loud Canadiana comedy. But, above all, it offers a very candid explanation for how and why B.C. came to be hailed as the green province. What is less clear, is why Colorado was out in front when it came to legalizing and commercializing marijuana on a major scale. If B.C. was so revered for its famous bud, why are Canadians still waiting to inhale? Despite Struthers’ sporting jabs at Justin Trudeau, there is no direct response to this question that hovers in the cloud of smoke that hangs over this text.

Finishing that section, I eagerly flipped over the book and settled in for another round of galloping prose through what I presumed would be an account of why not to support marijuana, or how it threatened to ruin lives or provincial economies, or some such stuff.

I was, however, completely mistaken. The Devil’s Weed is a very different text. As Struthers describes in his prologue, this section was written in two weeks; I believe it, because it reads as a stream of consciousness. Part Kerouac-styled travelogue, part Facebook-style story posts, The Devil’s Weed is an inside look at a culture of drugs, and the frenzied writing mimics the sometimes harried, paranoid, expansive, and/or mystical encounters one has in this context.

Written without paragraphs, and with punctuation and syntax to match one’s racing and at times incoherent thoughts, rather than a smooth narrative prose, this part of the book is confusing and difficult to digest. It offers dizzying detail at times, it borrows stories, and it includes a litany of references to places and things that are not always recognizable to the unacquainted reader. There is no clear direction or point, beyond a performance of writing or thinking under the influence of marijuana. Perhaps that is the point.

Together, these two very different accounts in a single bound volume offer an interesting and very candid contribution to the growing discussions on marijuana. Struthers does not hide behind academic posturing, policy-making intentions, or commercial opportunities, and instead hints at those debates while revealing a lot about his own experiences, and how his own journey has affected his views on much of the academic and medical literature that tries to defend or prohibit its use.

Consequently, The Sacred Herb reads as a logical, albeit an advocate’s, perspective on why society should not fear marijuana and its decriminalization. On the flipside, literally, we encounter an illogical, and at times nonsensical, view of life that is difficult to follow, let alone empathize with.

Consequently, The Sacred Herb reads as a logical, albeit an advocate’s, perspective on why society should not fear marijuana and its decriminalization. On the flipside, literally, we encounter an illogical, and at times nonsensical, view of life that is difficult to follow, let alone empathize with.

Clever marketing aside, this two-sided text takes advantage of a particular moment in Canadian history as we wrestle with questions about how, who, and what to regulate when it comes to mind-altering substances. Our collective experiences with marijuana seem to prove that the genie is out of the bottle. Anecdotal or not, it is the case that increasing numbers of Canadians have tried marijuana with minimal consequences, and many even articulate a growing list of benefits.

According to Struthers, police forces across the country have been turning a blind eye to this allegedly benign substance for a long time, suggesting that those on the front lines — teachers, police officers, physicians, social workers, etc. — have already worked out reasonable responses to marijuana use that do not necessarily rely on the cumbersome machinery of formal law and order. Changing the law, then, appears to merely align policy with practice.

So, the question is not whether marijuana should be legalized, but when the federal government will change its laws on pot. And when this happens, what effect will it have on B.C.’s green character? As Struthers makes clear, the allure of B.C. bud is only partly due to its THC content. If Canadians can soon legally order their marijuana from a carefully scrutinized menu, whether at a 7-11 or the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, the regional mystique of B.C. as Canada’s very own head shop may cease to retain that cultural connection.

The stories in Struthers’ book will then be seen as products of an older era, a period depicting home-grow-op techniques, police evasion, or the perils of trying strains with no idea of their potency. All of that cultural knowledge will slowly give way to a more regular set of interactions and a new set of stories with marijuana that unfold aboveground, and without halogen lights.

When that happens, will B.C. have to cultivate a new identity.

*

Erika Dyck is Canada Research Chair in History of Medicine and a professor in the Department of History at the University of Saskatchewan. Her books include Psychedelic Psychiatry: LSD on the Canadian Prairies (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008, reprinted by University of Manitoba Press, 2012); Facing Eugenics: Reproduction, Sterilization, and the Politics of Choice (University of Toronto Press, 2013); and Managing Madness: Weyburn Mental Hospital and the Transformation of Psychiatric Care in Canada (University of Manitoba Press, 2017).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply