#258 Reconciliation Manifesto

March 04th, 2018

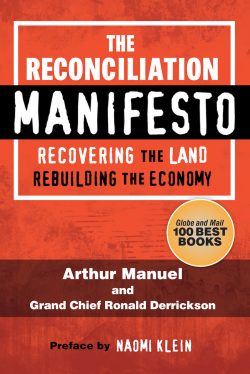

The Reconciliation Manifesto: Recovering the Land, Rebuilding the Economy

by Arthur Manuel (1951-2017) and Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson, with a preface by Naomi Klein

Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, 2017

$22.95 / 9781459409613

Reviewed by J.R. (Jim) Miller

In the conversation about reconciliation that Canadians are having at the moment, there are many voices vying for a hearing. One of the clearest and most emphatic of these voices — sadly stilled by death before the publication of this manifesto — is that of the late Arthur Manuel.

The Secwepemc leader had a lengthy, influential career advocating in support of Indigenous rights, especially the right to land, until his untimely death at Standing Rock in January 2017.

In The Reconciliation Manifesto, Manuel outlines his approach to the requirements of reconciliation, providing both negative and positive observations about the parties involved in discussions at the present time. His criticisms are divided almost equally between non-Indigenous political leaders and elected Indigenous leaders who cooperate with them.

So, for example, Justin Trudeau is another version of both his father Pierre and, improbably, Stephen Harper. The Conservative government’s 2012 policy proposals are no different from the White Paper of 1969, and Justin Trudeau has adopted Harper’s policies on climate and Indigenous affairs. Manuel is scathing about First Nations leaders elected under provisions of the Indian Act and more especially their national leader, the head of the Assembly of First Nations. The AFN, he charges, is not a nation that can deal with government on a nation-to-nation basis but “a lobby group that is funded almost 100 per cent by the government.” For Perry Bellegarde, Justin Trudeau is “the man who pays his salary” (p. 52).

Under such Indigenous and non-Indigenous leadership, governments repeatedly come up with stopgap measures “to fix Indigenous peoples.” This approach never works “because we are not broken. Canada is the sick one in the relationship, suffering from what sometimes seems like an incurable case of colonialism. It needs to change profoundly,” and Indigenous people must help them to change (p. 56).

Manuel is not without hope, however. He sees “a faint light on the horizon… the gradual dawning of awareness among ordinary Canadians that things are not right and things have to change….” Many Canadians “want to see reconciliation,” but “reconciliation has to pass first through the truth.… This book is an attempt to provide the truth that comes before reconciliation. And then try to plot where that new path may lead us” (p. 56).

Arthur Manuel’s “truth” is a plain, unvarnished account of Native-newcomer relations in Canada, focused principally on the issue of land ownership. He rightly sees, as one would expect of a British Columbian leader in particular, that the way settlers wrested control of land from Indigenous people constitutes a major, continuing wrong that needs to be addressed. His chapter on the acquisition of Indigenous land, “We Stole it Fair And Square,” is a potent indictment of the dispossession of Indigenous people by settler society. Returning to his theme of the continuity among Pierre Trudeau, Stephen Harper, and the current prime minister, Manuel asserts that, “Stealing land is a decidedly non-partisan, intergenerational activity in Canada.” (p. 106)

It is when Manuel turns to the question of how to act on his analysis of past wrongs and pursue a better future, that The Reconciliation Manifesto becomes less convincing. He recognizes that the courts have frequently been effective allies of First Nations in recent decades, but he remains critical of their approach to title questions in particular.

Even the game-changing Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Tsilhqot’in leaves him unconvinced and unsatisfied. He quotes the decision’s statement that when European sovereignty was asserted, “`the Crown acquired radical or underlying title to all the land in the province. This Crown title, however, was burdened by the pre-existing legal rights of Aboriginal people who occupied and used the land prior to European arrival’” (quoted on p. 110).

Saying that settler rights have higher priority than Indigenous property rights is “racism — the idea that white people have the inherent right to claim title to Indigenous lands, or the lands of black or brown peoples, and rule them as colonial masters. The final unspoken argument is always racism” (pp. 110-11). If the courts are an insufficient solution and political leadership is hopeless, where does that leave the Indigenous struggle for recognition of territorial rights?

At times, Manuel tilts toward emphasizing popular action, but never carries this part of his argument through to a conclusion. “We cannot let the government-paid leadership or even the chiefs [that is, hereditary chiefs] decide on the future of our land. People must have a direct voice,” he says (p. 139), though he doesn’t say how this is to be accomplished. He recognizes that populist challenges will provoke retaliation in the form of government cutting off funding to badly needed programs. “If we are going to do things that will threaten their lifelines, they [grassroots First Nations people] need to be part of the decision-making process. We must try to ensure that we do not put our people in an impossible situation, and we do this by working outside of the chiefs and council band structure, but always working closely with the grassroots” (p. 151). First Nations people are “spread across Canada in over a thousand locations, and they cannot take us all on at once” (p. 152).

Movements such as Defenders of the Land and Idle No More are part of the mechanism for linking grassroots people to action, but the mechanics of the linkage are not clear. “Indigenous peoples do not take action simply to confront the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or because we like going to jail or seeing our children and our Elders carted off in handcuffs. We do not take our liberty and the liberty of our families so lightly. But we see very few alternatives in Canada today” (p. 222).

As one might expect of the son of the leader who was one of the founders of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples, for Manuel the path to solutions is found outside Canada. Part 5 of The Reconciliation Manifesto, “The Family of Nations,” is cast very much in the spirit that animated George Manuel’s long and influential career. Arthur Manuel is a fan of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and he is legitimately, and rightly, affronted by Canadian governments’ one-step-forward, two-steps-back handling of the international agreement.

The government of Stephen Harper refused initially to sign on to UNDRIP, then gave ground and provided a qualified endorsement. Justin Trudeau initially was enthusiastic about the Declaration and purported to remove the qualifications his predecessor had issued, only to backpedal when the implications of UNDRIP’s “free, prior, and informed consent” clause became clear to him. Poor Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Reybould was dispatched to break the news to the Assembly of First Nations that the Trudeau government would not be putting the Declaration into legislative form.

Arthur Manuel emphasizes the things that the United Nations in particular can do to assist First Nations in Canada. He points out, for example, that UN commissions have often rebuked Canada for its mistreatment of Indigenous people, but he does not come to grips with the fact that such rebukes did not lead to government action.

Like many other commentators, he points to Sandra Lovelace — who, in 1982, took her loss of status as a result of marrying a non-status man to the UN Human Rights Committee and had her complaint upheld — to support his opinion that international opinion is influential in Canadian politics. According to Manuel, “the government was forced to change it [gender discrimination in the Indian Act] because of international obligations” (pp. 176-7).

What he and other commentators who favour international action overlook, however, is that the federal government was responding more to the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (CORAF) in 1982 when it enacted Bill C-31 in 1985. Full implementation of CORAF was suspended for three years under a delayed justiciablity agreement that was part of the 1982 negotiations, and therefore 1985 was the real deadline for implementing the Charter’s protections. The necessity to prepare for the full implementation of the Charter was the more important factor in the passage of C-31. International obligations played a relatively minor role. There is no chance of persuading champions of international fora of that fact, but it is the historical reality.

What he and other commentators who favour international action overlook, however, is that the federal government was responding more to the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (CORAF) in 1982 when it enacted Bill C-31 in 1985. Full implementation of CORAF was suspended for three years under a delayed justiciablity agreement that was part of the 1982 negotiations, and therefore 1985 was the real deadline for implementing the Charter’s protections. The necessity to prepare for the full implementation of the Charter was the more important factor in the passage of C-31. International obligations played a relatively minor role. There is no chance of persuading champions of international fora of that fact, but it is the historical reality.

Where, then, do these considerations leave The Reconciliation Manifesto as a guide for action for Canadians, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who want to support the movement to secure redress and reconciliation in this country? Arthur Manuel’s frequently powerful tract is a trenchant indictment of many of the problems that bedevil the country and challenge the reconciliation movement. His contention that reconciliation without redress of justice claims – especially over control of unextinguished Aboriginal title lands — is sound. If non-Native Canadians can be hectored into sympathy and support by rhetoric such as is found in The Reconciliation Manifesto, well and good.

If, however, it is more likely that Canadians of good will whom Manuel regards as “a faint light on the horizon” will be won to the cause of reconciliation by a well-reasoned case such as the one the Truth and Reconciliation Commission produced in 2015 and an appeal to fellow-feeling among people who share a land, this manifesto’s proposed tactics fall far short of its undoubtedly perceptive analysis. In a democratic country like Canada, which is the more likely path forward?

*

J.R. (Jim) Miller, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Saskatchewan, is a specialist in the history of Native-newcomer relations. He was the author of the first general history of relations between Indigenous peoples and immigrants in Canada, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada (1989; 4th ed., Feb. 2018); the first history of residential schools for Native children in Canada, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (1996); the first historical overview of treaties between the Canadian crown and Aboriginal peoples, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (2009); and the first historical examination of the reconciliation movement in Canada, Residential Schools and Reconciliation: Canada Confronts Its History (2017). He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and an Officer of the Order of Canada.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynne.

Leave a Reply