#107 Moodyville, mudflats & Maisie

March 22nd, 2017

REVIEW: Where Mountains Meet The Sea: an Illustrated History of the District of North Vancouver

by Daniel Francis

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2016.

$39.95. 978-1-55017-751-0

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

*

Daniel Francis, editor of the Encyclopedia of British Columbia and another twenty-four titles, turns his capable hand to local history in Where Mountains Meet the Sea, a book to commemorate the 125th anniversary – 1891-2016 — of the incorporation of the District of North Vancouver.

Reviewer Trevor Carolan follows Francis along the steep north shore of Burrard Inlet as he resurrects the cast of notable personalities, Indigenous and settler, who have called it home.Francis considers the origins of the community, its First Nations residents, its waterfront, industrial, and political history, and the development of resorts in the North Shore mountains and the District’s many parks. – Ed.

*

The District of North Vancouver marked its 125th civic anniversary in 2016, and as a municipality that has contributed an outsized share to B.C. history, it is appropriate that the North Vancouver Museum and Archives was able to sponsor publication of this well-researched, illustrated book by Daniel Francis in celebration.

This is a superb addition to our reading on the District of North Vancouver, and on the evolution of British Columbia’s own history as well.

Established along the shores of Burrard Inlet and beneath the dense “Green Wall” forests and the peaks of the Coast Range that define what Vancouverites know as the North Shore, the District was incorporated in 1891.

Originally it stretched from Horseshoe Bay to well up Indian Arm on Burrard Inlet — the Pacific coast’s southernmost fjord. As the author informs us, after a boom and bust struggle to survive as a lumber-milling and stevedoring settlement during the 1870s and 1880s, the community of Moodyville located across the inner harbour from what became the City of Vancouver, grew chiefly through the hard labour of both Indigenous and migrant labour in logging, sawmilling, shipping, and land selling.

In 1907, the original Moodyville shoreline area (depicted well in Where Mountains Meet The Sea through archival photographs), seceded with a tranche of the Lonsdale hillside area above to form the City of North Vancouver, a small, separate municipality.

Five years later, the District’s sparsely settled western region from Capilano Road to Horseshoe Bay established itself as the District of West Vancouver. Despite numerous grassroots attempts to amalgamate and save on the costs of supporting three separate civic bureaucracies serving a combined population of only 180,000, the three cooperated well in sharing a major hospital and some policing and public services.

Francis organizes his narrative not chronologically but contextually, and for the purposes of a general readership one cannot argue with this logic. He compiles rich histories and stories about the District’s waterfront, its history of building communities, and its renowned recreational proximity to a range of extraordinary natural ecologies.

The text is supported throughout by an expert compilation of photography and images of historical ephemera and memorabilia. Those familiar with North Vancouver’s social and cultural development from the past century will find the research and illustrations familiar and authoritative.

The book takes care to present the District of North Vancouver indigenous past too, through treatment of the Squamish and Tsleil Waututh First Nations, both of whom have been resident in the area from time immemorial.

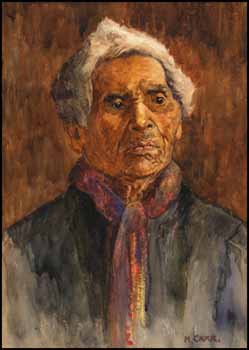

Locally loved figures such as chiefs August Jack Khatsahlano, Joe Capilano, and Dan George are given attention, as are lesser known but important figures like chiefs Simon Baker and Dominic Charlie, as well as Sophie Frank, who was Emily Carr’s friend for years and provided her with stories that turn up in Carr’s published tales.

Francis recounts how first European contact was made in 1792 when Spanish explorers under Jose Maria Narváez cautiously entered, but did not linger in, Burrard Inlet while searching for the Straits of Anian.

A year later, an English expedition under Captain George Vancouver arrived, as did further Spanish visits under Galiano and Valdes, which led to the first recorded encounters with the Tsleil Waututh.

Tragically, within forty years the Indigenous population would be decimated by as much as eighty percent from imported European diseases.

Francis does an admirable job of tracking how economic growth began with commercial lumber production in 1863, attracted by the District’s forests of enormous cedar and fir. Eventually, the waterfront mill-town area of Moodyville became established in what is now Lower Lonsdale and thrived for decades.

An 1867 Joint Indian Reserve Commissioner’s report noted that Indigenous residents of the North Shore’s three settled communities were active workers in the milling and stevedoring of lumber, “receiving between 75 cents and $1.50 a day.” As Francis observes, “they were active participants in the emerging economy of Burrard Inlet.”

By 1882 with the first electric lighting network north of San Francisco, North Vancouver began to prosper and by 1891 municipal status was achieved. Road expansion was financed by a land-sales promoter, James Cooper Keith, and one of the North Shore’s main arterials bears his name.

In short order, a litany of names made familiar by memorials in their honour began building and developing the District — John Mahon, Peter Larsen, Alfred St. George Hammersley, Thomas Nye Heywood, and others.

Inevitably, the big timber of Lynn Valley attracted expansion eastward and trees were skidded down to several mills before the McNair family, and then Julius Fromme, established the cedar-splitting mills that gave the Lynn Valley settlement both its old-time moniker of “Shaketown”, and an enduring reputation for working-class toughness.

An appealing element in the book’s design is its many entries on prominent citizens. Notables include Lynn Valley historian Walter Draycott; world-champion sprinter Harry Jerome; long-time publisher of The Native Voice, Maisie Hurley; mountain climbers Phyllis and Don Munday; community activist Mollie Nye; and early builder Navvy Jack Thomas.

Waterfront shipping, vessel-building, and ferry services have been integral to the District of North Vancouver and are well-covered here. As early as 1866, a sloop ferry ran across to New Brighton on the inlet’s south shore where the coach road to New Westminster began.

By 1889 the Union Steamship Co. launched vessels here and for half a century plied a flourishing trade along the coast. No chapter of local maritime history is more loved in North Vancouver, though, than the indomitable years of World War Two when the ship-builders of Burrard dry-dock helped keep Britain alive — a hurly-burly time when women-power stepped up and got the job done while the men were fighting overseas. The archival photos here are treasures.

The District of North Vancouver is a privileged community, as Francis’ capable writing confirms. Perhaps a little more acknowledgement of the ferocious public anti-residential growth campaigns that flourished here during the 1990s in making national news would not be amiss; otherwise, this is a terrific coffee-table history that’s worth sharing.

*

Trevor Carolan writes from Deep Cove, North Vancouver, where he served as an elected councillor between 1996 and 1999.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply