Love infinitesimally expanding

June 17th, 2019

Apostrophies VIII: Nothing Is But You and I

by E.D. Blodgett

Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019

$19.99 / 9781772124514

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

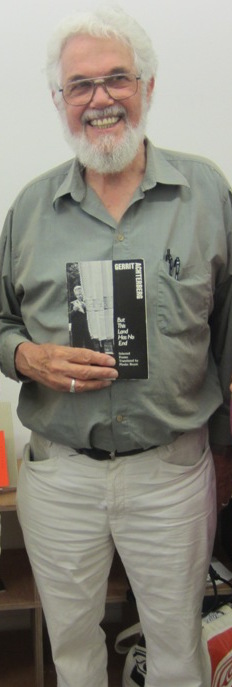

Born in Philadelphia in 1935, Ted (Edward Dickinson) Blodgett came to Canada in 1966 to teach at the University of Alberta. After serving as Edmonton’s poet laureate (2007-09), Blodgett moved to Surrey, where he died in November 2018.

His final book, Apostrophies VIII: Nothing Is But You and I consists of love poems to his wife of 27 years, Irena. These are no ordinary love poems, writes reviewer Christopher Levenson. “They are all suffused with, and celebrate, the tenderness, solicitude, and shared memories of a long relationship that is brought to life not just by mutual love but also by the cumulative emphasis on uncertainty, not knowing.”

This collection, continues Levenson, “creates its own microclimate, which allows the poems to conjure up and focus on unseen or unheard presences.” — Ed.

*

In the clamour of attention accorded recently to the deaths of poetic superstars Patrick Lane and Joe Rosenblatt, another major talent, that of E.D. Blodgett, who died last November in Surrey, seems in danger of being overlooked. Despite having published twenty-three volumes of his own poetry, and having won the Governor General’s Award for poetry in 1996 for his Apostrophes: Woman at a Piano, his work as a poet and as a translator has never courted popularity, nor in death is he ever likely to become a household word. As this posthumous volume amply demonstrates, he is too original for that.

In the clamour of attention accorded recently to the deaths of poetic superstars Patrick Lane and Joe Rosenblatt, another major talent, that of E.D. Blodgett, who died last November in Surrey, seems in danger of being overlooked. Despite having published twenty-three volumes of his own poetry, and having won the Governor General’s Award for poetry in 1996 for his Apostrophes: Woman at a Piano, his work as a poet and as a translator has never courted popularity, nor in death is he ever likely to become a household word. As this posthumous volume amply demonstrates, he is too original for that.

At a time when, whatever other stylistic features prevail, most poems that invoke the natural world are anchored to specific places and times, E.D. Blodgett’s work here is remarkably non-specific. He does not populate his poems with, say, Bohemian waxwings or pileated woodpeckers but with birds, while the woods he invokes are filled with trees and flowers rather than tamaracks and the lesser celandine. So too, apart from Trieste and Palestine, he names few actual places.

Why? Because they are all subordinated, mere walk-on parts in the scenery of an imagination that is focused on, and obsessively ruminates about, an ongoing love relationship, in all its changes and the growing awareness of impending death. By the same token such titles as “Beginning,” “Sky,” “Dissolution,” “Echoing,” and “Flowering” are mostly generic or abstract, Yet, against all expectation, it works.

How does it work? Strange though it may sound to put it that way, the secret is in the syntax and the highly personal sound that it creates.

Here is the whole of “Abiding:”

Trying to follow the drift of your mind growing slowly younger as

your hands unnoticed grow softer, how you turn to follow a bird’s

path

absorbed by certain measures of music or words in the language

that you spoke

when young, trying to fathom a world that is without the slightest

measure,

taking the summer of flowers in with well-remembered care,

Perhaps

an afternoon for single roses, full of awe as suns go down

over the bay, all your beliefs unshaken still and held in that

place where all the suns undisturbed still turn, no threnody

but theirs avails where, if the most ancient of light is traceable,

it abides, r in the first flower. What other drift does your mind

follow, there where love does not grow but infinitesimally

expands, the moment after the voices of singing children fall silent

but not a moment, rather an age where ice returns and

disappears

or single stars that flower, filling the night, until another appears?

Many of these poems, comprising two stanzas of fourteen to sixteen sinuously unfolding lines, contain only two or three sentences. This is not unique — the influence of Rilke, that master of the long, flexible colloquial line, is evident — but, apart perhaps from the late Don Coles no Canadian poet has proven so adept at handling and arranging multiple subordinate clauses and phrases in apposition so that all the twists and turns of a sequence of thoughts and feelings are presented in flux, seemingly as they occur.

Addressed to his wife and soon to be widow, these are no ordinary love poems. They are all suffused with, and celebrate, the tenderness, solicitude, and shared memories of a long relationship that is brought to life not just by mutual love but also by the cumulative emphasis on uncertainty, not knowing. Thus, transient states of mind and heart are paralleled and enacted by the fluidity of the cadences and of the sentence structure.

So, too, words and phrases such as “perhaps,” “you might say,” “how could I tell?” or “it’s possible” predominate, along with a penchant for the conditional and subjunctive moods and for the present participle, so that sometimes, as in “A woman sitting,” seven lines pass without a main verb, “Questions” ends with a question that has taken twelve lines to formulate, while in “Winter Dreams,” all twenty-one lines make up a single sentence, a feat only poets trained in classical grammar could manage.

In this way the book creates its own microclimate, which allows the poems to conjure up and focus on unseen or unheard presences, as here in “Waiting again:”

… not a dance for feet but something yet to be named,

calling out without a sound, and followed, as one follows

music never heard before.

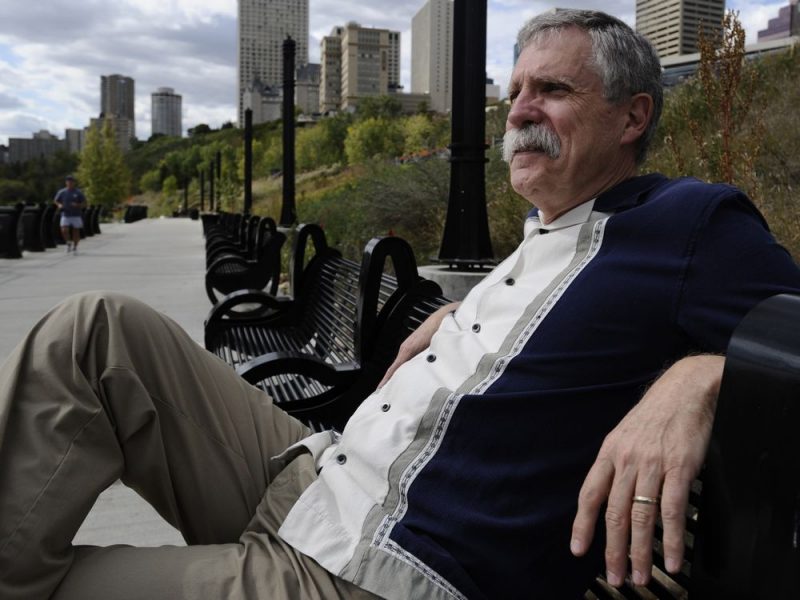

Ted Blodgett, Poet Laureate of Edmonton, on the North Saskatchewan River, Edmonton, 2008. Photo by Ed Kaiser, Edmonton Journal

Apart from the poetic skill involved, the mental and spiritual effort required to read it — even to oneself, let alone aloud — reinforces one of Blodgett’s main motifs throughout the book, the idea of becoming, which is something else that links him to the Rilke of the Duino Elegies and one of its injunctions, “Werde wesentlich,” that is, become essential.

Chary though I am of using the word “mystical,” I find myself suspending disbelief when he speaks, for instance, of “their souls like new birds suddenly aware of wings.” Of course there are occasional words or phrases that seem overwrought, but for the most part what Blodgett summons up in these meditations constitutes a spiritual and emotional journey that as readers we are privileged to overhear, to witness.

So, despite — indeed in a way because of — the apparent hesitations and tentativeness, what ultimately comes through is a kind of affirmation, a sense of revelation, a mutual bringing to light, and into words, a shared experience, a series of illuminations.

Read in sequence, the cumulative effect of these poems is not just a structural but also an emotional tour de force that will resonate at many levels.

*

Born London, England 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A tattered coat upon a stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his third wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series.

Leave a Reply