#163 Highways to tell

September 04th, 2017

At its AGM in Nakusp in May of 2018, the British Columbia Historical Federation announced the winner of its prestigious BC Lieutenant Governor’s Medal for historical writing is Ben Bradley for his book, British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of a Modern Landscape (UBC Press).

The $2,500 award was accepted for Ben Bradley by Doug Brigham, Collections Management & Planning Librarian at UBC Library.

BCHF delegates also voted to support BC Heritage Fairs throughout the province and provide financial assistance to the Ormbsy Review, an online journal for reviews about BC history and literature, named in honour of Canadian historian and former BCHF president, Margaret Ormsby.

Delegates learned more about the legacy of the 1964 Columbia River Treaty and the flooding of communities. Many villages, homes, and farms were lost. Residents are keenly watching impending treaty talks.

Delegates learned more about the legacy of the 1964 Columbia River Treaty and the flooding of communities. Many villages, homes, and farms were lost. Residents are keenly watching impending treaty talks.

The British Columbia Historical Federation encourages interest in the history of British Columbia through research, presentation, and support in its role as an umbrella organization for provincial historical societies.

Learn more about the British Columbia Historical Federation at their website: http://www.bchistory.ca/.

Photos by Darren Durupt

Historical Writing Awards Chair Maurice Guibord, with Doug Brigham, Collections Management & Planning Librarian at UBC Library, and President of the BCHF K. Jane Watt.

*

REVIEW: British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of a Modern Landscape.

by Ben Bradley

UBC Press, 2017. $34.95 sc $89.95 hc

Reviewed by Daniel Francis

In 2013 a septet of Canadian historians calling themselves The Past Collective published a study which contradicted the hoary old cliche that Canadians do not know a lot, or care that much, about their own history. Not so, said the professors. We are not a nation of historical amnesiacs. Using the results from a series of surveys, the authors concluded, in a book called Canadians and Their Pasts (University of Toronto Press), that we actually know quite a lot about our past, certainly as much as citizens of any other country.

The study of history is usually understood to be something that takes place in the classroom, and only in the classroom. But the Collective pointed out that there are multiple other ways that people engage with the past, from watching television documentaries to tracing their ancestors on the internet to researching the history of their own home. All of these activities, and many others, reflect an interest in, and imply a knowledge of, the past.

The study of history is usually understood to be something that takes place in the classroom, and only in the classroom. But the Collective pointed out that there are multiple other ways that people engage with the past, from watching television documentaries to tracing their ancestors on the internet to researching the history of their own home. All of these activities, and many others, reflect an interest in, and imply a knowledge of, the past.

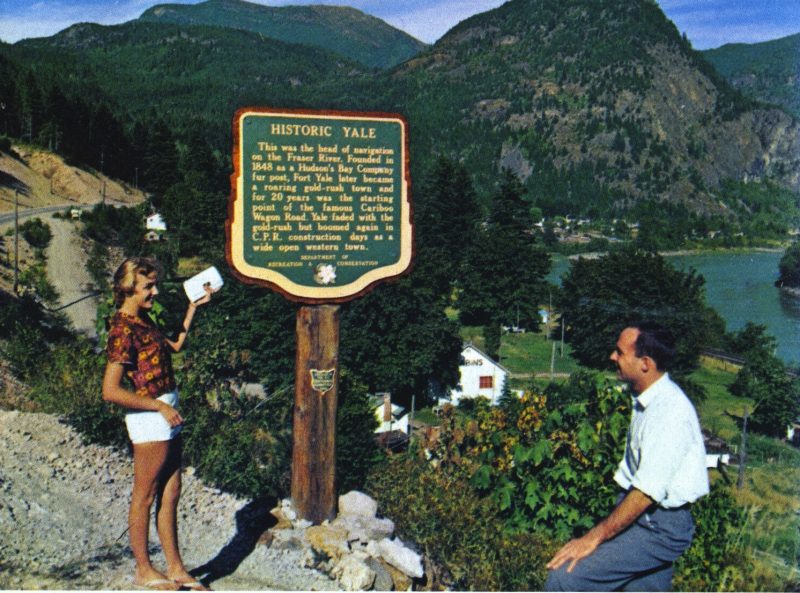

One of the ways that we experience our past is by driving through it. We hop into our automobiles and motor through the backcountry, stopping along the way at a wide variety of historical markers, parks, and viewpoints to refresh our memories or learn something new. This “public pedagogy” goes a long way to informing the ideas we have about our province’s history and it is the subject of Ben Bradley’s new book, British Columbia by the Road.

It is surprising to be reminded how recently British Columbia was joined together by a network of highways. Until the Fraser Canyon highway opened in 1927 there was no road connection between the coast and the interior of the province. The only way to reach the Okanagan by car, say, or the Kootenays, was to dip south of the border. It took another thirteen years before automobilists could drive from Alberta to the coast entirely within B.C. via the Big Bend Highway.

And then, in 1949, the much-delayed Hope-Princeton Highway finally opened a southern route through the province. The story of these three highways — their construction and their relationship to park development and historical sites — forms the core of Bradley’s engaging book.

He begins with the Hope-Princeton. Bradley contends that provincial parks were developed largely as an extension of the highway network. In the case of the Hope-Princeton, the road was built to provide motorists with access to Manning Park. Located in the Cascade Mountains east of Hope, it was established in 1941 and named for Ernest C. Manning, former chief forester and parks promoter who had died in a plane crash earlier in the year (and father of Helen Akrigg, author of the handy British Columbia Place Names, UBC Press, 1997 – Ed.).

Bradley shows how Manning Park was groomed to appeal to the motoring public. Groves of wild Rhododendron, stands of majestic old-growth timber, and bluffs of mountain goat habitat were all identified as roadside attractions. Scenic lookouts were built and signs of industrial activity hidden. The Manning Park “wilderness” was in fact a carefully crafted “natural” landscape in which sights were manipulated to show B.C. at its best. As the “crown jewel of the park system,” writes Bradley, “few other provincial parks were as carefully and lavishly tended as Manning was” (63).

Next on his itinerary is the decidedly less edifying story of the Big Bend Highway. By 1927 a single gap remained in the road between Calgary and Vancouver, a 110-kilometre stretch between Golden and Revelstoke across the Selkirk Mountains. Engineers considered it impassable. Instead, the province and Ottawa agreed on an alternative route, almost three times as long, following the “Big Bend” of the Columbia River.

Built during the Depression as an unemployment relief project, the road took ten years to complete, finally opening in June 1940. A year later the province created Hamber Provincial Park, a huge wilderness area on the eastern flank of the new highway contiguous to the Rocky Mountain parks already established by Ottawa.

Neither the park nor the highway worked out as intended. The Big Bend was a frightening drive that most travellers chose to avoid. It was a narrow, dusty, gravel road with precipitous drop-offs and no one to come to a stranded motorist’s rescue. Snow closed it during the winter. One journalist called it “the loneliest road in North America” and recommended that anyone travelling between Revelstoke and Golden ship their vehicle by rail instead.

Hamber Park was equally disappointing. The province had intended all along that the federal government should take it over but Ottawa had no interest in doing so and the park languished: remote, not particularly scenic, without historic or natural attractions. Eventually, the province gave in to pressure from loggers and sharply reduced the size of the park.

In 1962 the Rogers Pass route replaced the road around the Big Bend; hydro dam construction flooded most of the old highway during the 1970s. Instead of a wilderness playground like Manning Park, Big Bend country and the bulk — 98 percent — of Hamber Park were sacrificed to the demands of loggers and hydro engineers.

Lastly, Bradley examines the Fraser Canyon Highway and the development of historical resources in the Cariboo, chiefly Barkerville Historic Town. The road through the canyon follows the route pioneered by the famed Cariboo Wagon Road, completed in 1865 to provide access to the gold camps of the Cariboo Mountains. The original road was later degraded by railway construction but it was resurrected for motorists in the 1920s. “With its intermingling of sublime scenery, intimidating terrain, and remnants from the past, the Canyon Highway became British Columbia’s premier drive,” writes Bradley (122), and it remains so today.

With the road in place all the way to Prince George, entrepreneurs stepped in to establish a variety of roadside accommodations and attractions for the motoring public. When the centennial of the foundation of the colony of B.C. rolled around in 1958 it proved a perfect excuse to ramp up historical activities along the highway, including a new set of plaques designating “Stops of Interest” and the restoration of the old townsite of Barkerville as an historic park.

By 1970, Bradley observes, “the highways of the BC Interior seemed to be increasingly awash with old-timey ghost town parks, outdoor museums, living museums, and local museums” (229). Not all were as successful as Barkerville, but all played a role in shaping the public’s understanding of the province’s history.

Every bit as much as the classroom, the highway was where British Columbians obtained their history education. Bradley suggests that roadside attractions, from kitschy souvenir shops and bogus ghost towns like Three-Valley Gap, to state-sponsored parks like Barkerville, play a crucial role in building historical awareness.

For all the freedom of the open road, it is the state that chooses what motorists see and experience along the way. Especially after 1958, “the view from the road” was carefully curated to represent a benign, uncontentious version of provincial history. “It was important,” writes Bradley, “that history be eye catching, lively and accessible but not that it be necessarily accurate or profound” (241).

For an academic book, British Columbia by the Road is refreshingly free of jargon and smoothly written; it also presents a thought-provoking new perspective on the history of B.C.’s interior.

*

Historian Daniel Francis, arguably the province’s hardest-working and prolific popular historian, edited the most essential book about the province, the Encyclopedia of British Columbia (Harbour, 2000), having previously worked as an editor for Mel Hurtig’s Encyclopedia of Canada. Francis has also written the definitive biography of Louis Denison Taylor, which received the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2004. For more information about Francis and his twenty-six books, see his entry on ABCBookWorld.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply