Having a baby

May 27th, 2021

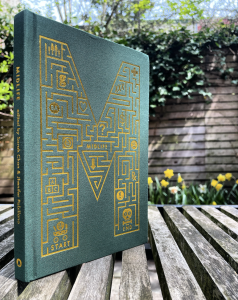

With extra time on their hands during the pandemic, Jhenifer Pabillano and her friend Sarah Chan reconnected (remotely) with 27 friends and colleagues who had all met while all working at a university student newspaper. They wanted a writing project to work on and within three months, the group had produced a 140-page book of sharp, funny reflections on their life experiences after university, Midlife (Chan-Pabillano Initiative, $40).

The following excerpt is Jhenifer Pabillano’s contribution to the collection, Illusions.

*

When we first got pregnant, it was an intellectual decision. It was on our five-year plan, after my husband and I had finished grad school, had our wedding, and been in full-time jobs for a while. I thought we should try for kids before I turned 30, since it was supposed to be the least difficult time to get pregnant. The effort was put in, and the pregnancy ensued.

I had not been the kind of girl who dreamed of being a mother, so I had no expectations going into it. A strange reality dawned as the pregnancy progressed. Pregnancy, for me, was a benign version of Alien, not the soft-focused Nancy Meyers movie I subconsciously expected. You are a normal person whose body rapidly becomes a host for another, and there’s nothing to do but endure the pregnancy as it changes you—sometimes with grace, sometimes not. Blood volume doubled, nausea descended, hormones ran high, ligaments loosened, acne bloomed. My feet smelled terrible, and my belly grew like Violet Beauregarde, swelling up into a round balloon on the Wonka factory floor.

The pregnant belly was particularly different from what I had imagined. I had assumed the belly would feel nurturing, warm, and soft in some way, but as it emerged, it felt like a tight, heavy basketball pressing itself out under my skin—taut and hard, a defensive shell to protect the organism within. It stretched my belly, not caring if the skin cracked or hurt or grew scars. I was rudely awakened to the fact that my life, which I had previously thought deeply under my control, was actually subject to the limitations and programming prescribed by my body. It is a myth that the conscious mind, however it feels itself the master of all it surveys, is ever truly the sole architect of our lives.

The day of the birth loomed. One thing you don’t fully realize when you initiate a pregnancy on a voluntary basis (and if it progresses reasonably well, touch wood) is that there really is no getting out of it. No take-backs, no return policy. Thirty-nine to 40 weeks after conception comes a baby, whether you’re ready for it or not.

In our case, we were as ready as you could be as first-time parents. We took a seven-week (!) prenatal class where we saw videos of births, created a birth plan, learned techniques to manage pain through the stages of a days-long labour. But when birth started for me, it took just three hours to enter active labour after the first light contractions started. Active labour is the stage when the baby is ready to be born, and three hours is an instant in pregnancy time.

The birth plan fell away. Instead, I went with the ad hoc tactic of kneeling on the bathroom floor and screaming with every contraction. Each cramp felt like being stabbed in the abdomen from the inside, or perhaps being tasered internally for a full minute before a short pause, then repeating. Calls to our midwife failed—she was meant to answer within 10 minutes after receiving a page but didn’t respond until an hour later. By that time, we had followed the escalation instructions given to us and were in an ambulance to the hospital. Our daughter was born shortly after, delivered by two exasperated emergency room doctors who slapped a gun of nitrous oxide into my hand and told me to breathe in liberally whenever I felt the pain. It was miraculous and amazing—the nitrous oxide, I mean. The baby itself, which the doctors had dumped on my chest, looked like a complete alien—red and squishy, its weird mushy face and coal-black eyes moving in slow strange ways.

Another reality was dawning. My only true experience of seeing pregnancy and birth was in movies or TV, where labour involved pain and effort, but a transformation took place for the mother at the end when the child was brought to their arms. The mother’s eyes welled with tears, she blubbered, she was enamoured with the baby. I waited for this transformation when my daughter emerged—for motherhood to wash over me in a tsunami of feeling.

It didn’t happen. Despite my body’s processes, my mind as I had always known it was still there. The same mind that I had lived with my entire life felt secure and wholly intact, quietly whirring away, processing everything as it always had. Having a child did not mean I had lost myself. A sense of pure freedom from expectation descended and has not left me since. I looked down at my newborn child, whom I would grow to love deeply over the coming year, took in its misshapen body slathered in blood and tissue, and said exactly what I thought, in a voice slurred and stretched out by great inhalations of nitrous oxide: “What is it?”

After the baby was born, another “birth” of sorts occurred. Out came the placenta, a dark and fleshy pile of guts shaped like a hot water bottle, which my body had created to nourish and protect the baby this entire time. It sloshed around in a metal basin like a murky, blood-red jellyfish. Its presence slid another lens over my view of the world, driving home the animal reality of human bodies in full HD.

I looked up then at all the humans working busily around me and saw with stinging clarity that I was not the first, not even close, to have ever gone through this experience. A person standing before me meant that someone had given birth to this person, and someone had given birth to her, and so on and so forth. It was obvious but also the first time I had truly understood this. Those of us who bear children, all through time, have always endured an almost total metamorphosis of the body to create our whole species, every single human around us. My whole primal birth experience was that of women throughout history: since forever we had all been flooded with strange musks, torrents of blood, and the actual tearing of flesh.

It occurred to me then that I had been a tremendous snob about pregnancy and childbirth. I had never had any real discussion beyond social pleasantries with people who were pregnant, and to be honest, I had consciously avoided any interest in them or their eventual offspring. I wasn’t the person who went to play with the kids at a party, or cooed over someone’s pregnancy announcement. It had seemed to me that showing interest in pregnancy and babies demonstrated some kind of weakness of character. They were a deliberate act of a particular type of femininity, or a cliché topic to be avoided and stepped around.

I was in my 20s, and it was important to me to seem knowing and cosmopolitan. I had not realized that in doing so, I had entirely absorbed society’s messages that women and their lives were inferior—something to be dismissed rather than seen and recognized, something not worthy of engaging my full attention. It was unbelievable that I had not questioned my assumptions and tried to look closer, to find a smidgen of interest in the foundational event of human life. How ridiculous it was that I thought there was nothing to see, nothing to learn from, when women—half our world!—were experiencing such an extraordinary transformation, and navigating all the philosophical and identity issues that came along with creating life while steering your own.

At prenatal class before, I had avoided engaging with the other parents, doing that thing where you try to seem cool by rationing out your attention, like a precious gift. After having a child, this fell away. One of the women in our class became a close friend during maternity leave. I saw her clearly now—a sister who had been through the war with me, and, like returning soldiers, we had come through changed. Sometimes these are the only people you can talk to when so many around you are caught up in illusions of the world.

Since then, I try to come to the world with humility and a desire to witness and to question. I want to engage with life as it is actually lived and not the tricks that my mind plays. Any time I want to skip over somebody’s experience in my head, any time I see a blank spot or feel derisive about somebody’s life events, I think carefully about why, and I try to look closer.

There is also more patience and grace in the mix. Before, I would look at those who act knowing and in control, and I would think they seemed so superior and intimidating—something I should aspire to. I don’t think that anymore, and I don’t think, as I might have in the past, that it’s my place to tear away their blinkers or shout my revelations at them.

Mostly, I just want to give them a hug. And, if they were interested in hearing me, I would tell them that appearing blasé and detached about life doesn’t actually show you’re cool or somehow above the rest of us. I would tell them that for me, it just meant that I was asleep to the fact that extraordinary things happen around us all the time. These things may look ordinary—parts of patterns that occur and recur all around us. It’s so human not to notice, I would say. If only we all could see. 978-1-7775473-0-1

*

Jhenifer Pabillano is a project manager with the City of Vancouver. Previously, she was the Communications Manager for the City’s 2018 municipal election, and spent five years as the City’s first ever Social Media Strategist. She holds a Master of Journalism from UBC and a BA from the U of A.

Leave a Reply