#124 Grappling with Indian apples

April 25th, 2017

Chief Tetlenitsa’s Apples: Commercializing Indigenous Horticulture in British Columbia, 1907-1916

By Michael Sasges

*

John Tetlenitsa, chief of the Nlaka’pamux nation, was a collaborator with ethnographers Marius Barbeau and James Teit. Michael Sasges revisits Tetlenitsa’s challenges to officialdom after Merritt City Council prevented him from selling 40 boxes of apples from his orchard in 1916.

*

We are pleased to present another Nicola Valley article by Michael Sasges.

On November 7, 2016, The Ormsby Review (No. 39) presented his story “From Quilchena Creek to Flanders,” concerning the life of John Nash, an English-born rancher who died in battle at Belgium in April 1916.

Now Sasges tells the story, also from 1916, of orchardist Chief John Tetlenitsa of Spences Bridge who took a wagon load of 40 boxes of apples into Merritt, the new town in the Nicola Valley, only to have the Chief Constable seize the apples and fine him $25 for selling his apples door-to-door without a “pedlar’s licence.”

Much recent historical scholarship in B.C. has concerned the impact of residential schools on Indigenous people, starting with Elizabeth Furniss, Victims of Benevolence: The Dark Legacy of the Williams Lake Residential School (Arsenal Pulp Press, 1995), and the process of Indigenous dispossession and reserve creation, most notably Cole Harris, Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia (UBC Press, 2002).

Now Mike Sasges opens a new and equally troubling window into how Indigenous people were discouraged from doing business in small towns like Merritt by a range of municipal bylaws, fines, and permits.

Sasges shows how the Kamloops Indian Agent, John Fremont Smith, and his bosses at the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa were unable to protect the enterprising Chief Tetlenitsa from the punitive measures of the newly-formed Merritt City Council. — Ed.

*

Malus sylvestris . . . (Cultivated Apple) … /qw?ép-s e /séme? (lit. “whiteman’s crab apple”– see Malus fusca). — Nancy Turner, 1990[1]

In late summer 1916, Chief John Tetlenitsa, a Nlaka’pamux (Thompson) farmer and orchardist took his apples into the City of Merritt and sold them door to door, by the box, from the back of his wagon. The city’s chief constable charged him with retailing without a business licence issued by the city, seized and impounded forty boxes of Tetlenitsa’s apples, and forced him to pay $25 for their return.

The Kamloops Indian Agent, John Smith, was aghast when he received Tetlenitsa’s telegraphed request for assistance. He considered the impoundment and fine unprecedented and unjustified. The public purse of this five-year-old municipality had benefited by outlawing what Smith considered legitimate Indigenous economic behaviour. “The Town of Merritt is the first in this province to my knowledge that has attempt[ed] to extort money from an Indian for selling his produce within their limits.”[2]

Smith also informed his superiors in the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA) of his own contribution to Tetlenitsa’s excursion from Cook’s Ferry (Spence’s Bridge) to Merritt. Smith revealed that under his auspices, the Kamloops Indian Agency had invested money in Tetlenitsa’s visit:

Chief Titlanetza found himself unable to secure boxes in which to pack his fruits when they were ready for the market, and applied to me for assistance. I bought him 300 apple boxes and 50 plumb (sic) boxes … [and] I prepaid freight to the [railway] siding within a short distance from his Orchard.[3]

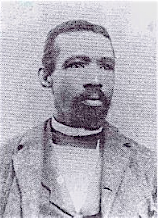

John Fremont Smith was a veteran of small town B.C. politics. When he wrote to DIA headquarters in November 1916 that the Merritt fruit seizure was unprecedented, his was an informed opinion: between 1902 and 1912 he had been, at various times, a Kamloops alderman and city assessor. “The City of Kamloops,” he noted in November 1916, “is the largest in the Interior, and with stringent Bylaws governing trade…. The Indians sell their produce with impunity to any one.”[4]

Born in 1850 in the Danish West Indies (now the United States Virgin Islands), Smith was the Kamloops Indian Agent from 1912 to 1923. He had arrived in Victoria in 1872, and between 1877 and 1911, his occupations were listed as boot and shoemaker, journalist, and Kamloops real estate agent.[5]

The seizure of the apples and the fine would humble these two Thompson countryside notables, Tetlenitsa and Smith, and the impoundment was also a humiliation for the DIA. It showed the primacy of the municipal level of settler government over the federal level, which was intended to protect and promote Indigenous horticultural interests.

In fact, Chief Tetlenitsa’s apples had received the stamp of approval of another branch of the federal government. Since 1907, DIA and the Dominion Agriculture Department had received a parliamentary appropriation to conduct an agriculture-extension and fruit-hygiene campaign among the Indigenous peoples of British Columbia.[6] The DIA had hired an “Inspector of Indian Orchards for British Columbia,” a Scottish immigrant named Tom Wilson, whose job included the “cleansing” and “cleaning” of reserve orchards with a combination of tools including arsenate of lead, fire, and steel.[7]

Allegations had been made about unhygienic conditions on reserve orchards, resulting in a horticultural hygiene regime that led to Wilson’s appointment. Complaints by settler orchardists and local authorities justified “Indian Orchards” work. In 1905, members of the B.C. Fruit Growers’ Association directed their secretary to ask the Dominion government to find money “for the purpose of cleaning the orchards of the Indians in this Province.” A Chilliwack orchardist stated that “another source of disease was the Indian orchards,” and he hoped that “some means would be found of keeping them clean.”[8]

In 1910, Wilson noted that “white people” and “provincial authorities” had complained to him about the condition of reserve orchards in the Fraser Canyon, while the City of Victoria complained “that … tent caterpillars [from] Indian reserves were invading the city.” A similar situation prevailed on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Wilson “supplied the Indians with kerosene oil and torches, and burnt the nests.”

Chief Tetlenitsa’s venture was precisely the kind of project, based on clean, hygienic, and regulated orchards, that federal agencies had hoped to encourage.

In a broad sense, the record presented here of the activities of Chief Tetlenitsa, Indian Agent Smith, and farm inspector Wilson reveals the food-production practices of the province’s Indigenous peoples on their remnant territories almost a hundred years after mariners and fur traders started to grow fruit, grains, and vegetables in the western Cordillera.[9] This article aims to fill a gap in the literature. Thanks to the remarkable ethnobotanical insights generated by the University of Victoria’s Nancy Turner, based on her collaboration with Indigenous informants, elders, and collaborators, today we probably know more about the food-production practices of the Indigenous peoples of what would become British Columbia a thousand years ago than about food-production practices in 1910.[10]

The activities of Tetlenitsa, Smith, and Wilson also offer a glimpse of the Dominion government’s mission civilisatrice in B.C. That civilizing purpose is probably better known for its pedagogic expression in the residential schools than its agricultural expression both on Indian Reserves and on the grounds of residential schools. Its purpose was the imposition of a household and commercial settler-agriculture sensibility on the Indigenous farmers whose orchards and gardens were located in the vicinity of urban markets or the railways that connected urban markets and their hinterlands.

The underlying irony and incongruity is that Tetlenisa’s strong agriculturalism was a basic part of the ideology of reserve creation in B.C., as Cole Harris has shown. A settled and sedentary life was considered superior to one based on hunting and fishing over what was, by the 1860s, Crown land. Yet a generation later, a high-ranking entrepreneurial Indigenous farmer was successfully barred from participating in the market economy of settler B.C.[11]

*

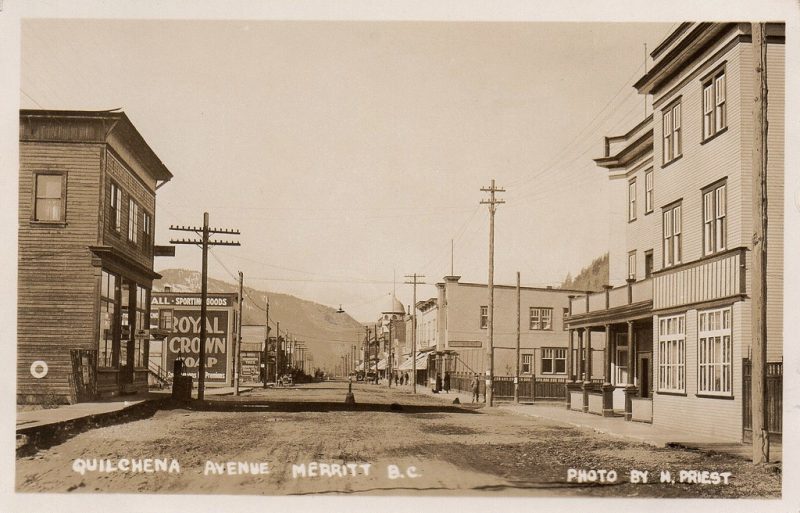

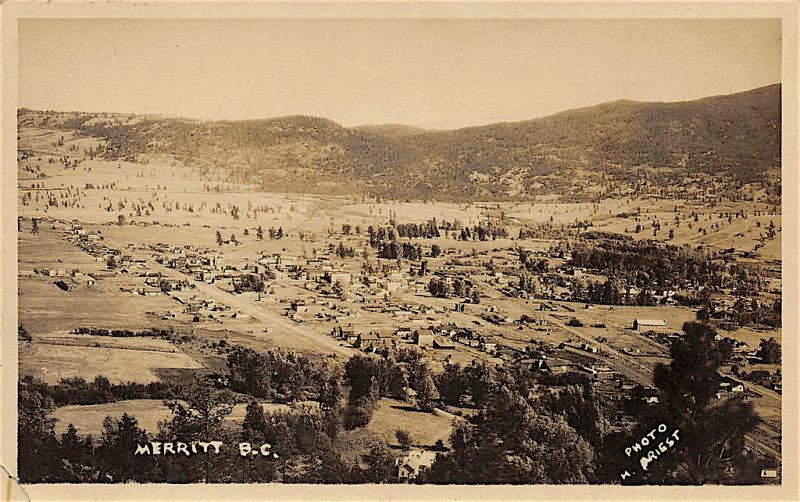

When John Tetlenitsa made his business trip to Merritt in late summer 1916, he was doing what DIA had been encouraging Indigenous horticulturalists to do for some years: selling his produce to buyers in communities like Merritt. The Nicola Valley was recently industrialized and urbanized. A short line, completed in 1907, connected the CPR mainline at Spences Bridge to the Merritt Coalfield at the confluence of the Coldwater and Nicola rivers.[12] Between 1901 and 1911, the settler population in the vicinity of “the Forks” had increased almost six-fold. Merritt boasted a city council, city clerk, a city constable or two, jail, volunteer fire department, firehall, two weekly newspapers, three hotels, four churches, and an armoury.[13]

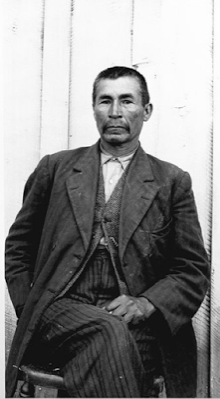

An important Nlaka’pamux collaborator of ethnographers Marius Barbeau and James Teit, John Tetlenitsa, as a chief of the Nlaka’pamux nation, helped organize Indigenous challenges to government policies relating to land, life, and resources. And he had support: two other leaders of Indigenous land-and-rights agitations lived in or near the Nicola valley: Teit, a resident of Spences Bridge, across the Thompson from Tetlenitsa and his Cook’s Ferry people, and John Chelahitsa, a Syilx leader and resident of the upper valley.[14]

Tetlenitsa’s portraits, songs, and stories are housed at the Canadian Museum of Civilization. His political activities were also notable. In the summer of 1910, he had joined the famous memorial presented by “the Chiefs of the Shuswap, Okanagan and Couteau Tribes of British Columbia” to Prime Minister Laurier at Kamloops. In November 1913, he had given testimony at the (McKenna-McBride) Royal Commission on Indian Affairs for the Province of British Columbia at Spences Bridge, and just months before facing the wrath of the Merritt town council, had taken part in the “Deputation of Indian Representatives [of the] Tribes in British Columbia, upon Sir Wilfred Laurier, Parliament House, Ottawa, April 27, 1916.”[15]

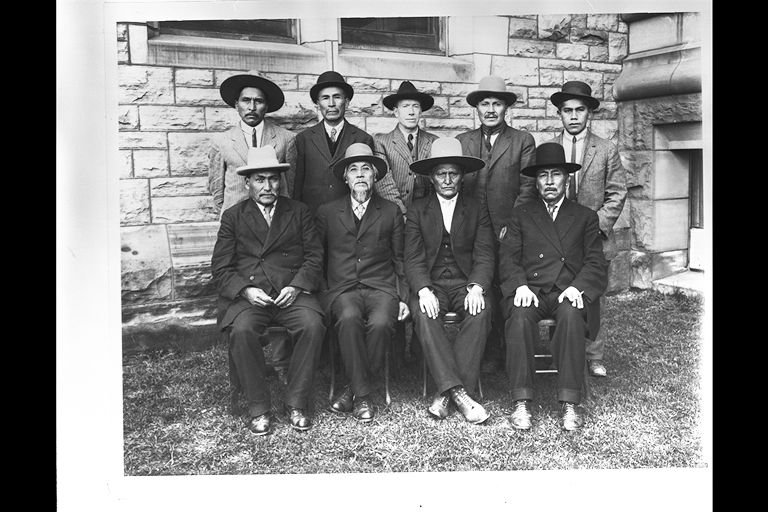

Edward Sapir’s photo of the “Delegation of Indian Chiefs from Western Canada sent to Ottawa, 1916” shows John Tetlenitsa four months before his fruit was seized in Merritt and, further, that three Indigenous leaders of the land-and-rights agitations in the first years of the previous century lived in, or in the vicinity of, the Nicola Valley. Tetllenitsa is standing second from left, James Teit to his left. John Chelahitsa, a Syilx leader from Douglas Lake country, is seated immediately below Tetlenitsa.

On his Ottawa trip, Tetlenitsa and other Indigenous leaders shared, with anybody who would listen, their aspirations for their people. Tetlenitsa’s Ottawa visit occurred five months before the burghers of Merritt impounded his fruit.

By 1910, Tetlenitsa had farmed in the vicinity of the confluence of the Nicola and Thompson rivers, near Spences Bridge, for three decades. In the 1881 census “Teetliheetsa, John” was of “full age” and his occupation was farmer. Seven other people resided with him; two men of full age, also farmers; two women of full age, one of whom, Susan, was his wife; and three toddlers, one of them John and Susan’s child. In the 1891 census, “Tilaheetsa” (occupation, farmer) and Susan were husband and wife and the parents of eleven-year-old Lena.

In 1910, gardening and orcharding were the principle livelihood of Chief Tetlenitsa and some of his people. They demonstrated a high degree of horticultural mastery. “We very nearly make all our living off the land, but when times are hard, that is when water is scarce, we go out to work,” he told the members of the McKenna-McBride Commission in November 1913 during their visit to the Cook’s Ferry reserves. Seven households raised “hay and clover, potatoes, turnips, beans, peas, apples, oats, wheat, pears, cherries — all kinds of fruit, grain, and vegetables,” Tetlenitsa reported, on seventy acres on two reserves.[16] In the same month, Agent Smith reported that seven Cook’s Ferry households cultivated 500 acres, that Tetlenitsa cultivated sixty of those acres, and that “he is preparing forty acres more.”[17]

In his presentation to the McKenna-McBride Commission, Tetlenitsa complained that no road connected their gardens and vegetables with potential customers, near or far. They used packhorses to move their harvest to the Nicola wagon road. “Often times when we get to the end of our journey,” he said, “the apples are all bruised and we cannot get the price for them which we otherwise would get.” That is, his harvests lost value because of a farm-to-market deficiency.

The McKenna-McBride Commission members then asked:

Q: Do you know whether any proposal was ever made by the Indian Department to build a wagon road from your reserve?

- Years ago I spoke to Mr. Irwin, [the previous Kamloops agent], and I told him that he should build us a road, because we were still packing on horseback, the same as we did over 100 years ago, and now we have trains going by almost every minute, and we are still packing our goods to market on horse back.

Q: Did Mr. Irwin not do anything?

A: Mr. Irwin said “Very well, I shall help you, but the only way I can do it, is that I will give you 400 dollars to build five miles of road with. When you have done that, I shall get the Victoria Government to help you further on.” They have not done anything since.[18]

Agent Smith, however, reported that the DIA had welched. They had not supported Irwin’s promise. “They informed me they had no funds to apply for that purpose,” Smith said during his examination by members of the royal commission. And the provincial government declined to contribute to the construction of the road “because no one would be using it but the Indians.” Yes, he agreed with a commissioner, he “would construe that to mean that they had rescinded their previous offer.”

Smith thought the situation ironic: he had a received a letter from the provincial agriculture department praising the quality of the Cook’s Ferry produce included in a recent provincial exhibit at an exhibition in Chicago. “ … and yet they cannot get a road to take that stuff out.”

*

The Cook’s Ferry households were not the only Indigenous farmers raising fruit, as can be gauged by the work of Tom Wilson, the Inspector of Indian Orchards in B.C.

Wilson was a Firth of Forth Scot, born in 1854 in Musselburgh, an ancient settlement on the great estuary’s south shore. He may have trained as a horticulturist at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh and worked there as a foreman. He then passed six years in India and Burma supervising tea plantations. He arrived in Canada in 1885 and reached B.C. a year later on a CPR construction crew. He liked to say that owing to his work on the CPR mainline, he had “walked into British Columbia.” He was joined in 1887 by his wife, Alice, also from Edinburgh.[19]

Wilson passed 1895 and 1896 in the Okanagan, managing the tree-fruit operations of Lord and Lady Aberdeen’s Coldstream Ranch, near Vernon. The 25,000 fruit trees the couple planted in 1892 were one start on the Okanagan’s tree-fruit future. Wilson’s two years at the ranch probably coincided with the first harvests. He was appointed a provincial government fruit inspector in 1896, the Dominion government’s first supervisor of plant fumigation for B.C. in 1900, followed by Inspector of Indian Orchards in 1907.[20]

By then, Tom Wilson had farmed and worked for agriculture departments of government in B.C. for twenty years. He contributed to the start and acceleration of the transformation of the Okanagan countryside into one of five tree-fruit-growing geographies in Canada, and one of six in the North American Cordillera,[21] and he was a confidante of the Dominion agriculture executive who helped to craft the “Indian Orchards” partnership.[22]

Wilson’s duties after 1907 varied. Money was available to purchase spraying equipment and to instruct Indigenous orchardists in their operation and maintenance, and to ensure the safe carriage and application of poisons. Those expenditures were a response to complaints from settler orchardists and provincial and municipal governments. Money was also available to purchase replacements for Indigenous people’s diseased trees destroyed at Wilson’s own orders. These expenditures were a response to complaints from Indigenous farmers about the loss of productive trees. But there was little money for reclamation and farm-to-market projects, and the DIA was disinclined to pay for irrigation to connect water with Indigenous land.

Wilson also kept an eye on the growing settler orchards of the larger Edwardian “fruit mania” in B.C.[23] He complained that some the older settler-orchardists were small farmers who produced bad fruit and possessed rudimentary knowledge of orchard care, fungicide, and pesticide, and that their knowledge of grading and packing techniques was minimal.[24]

*

Many other Indigenous communities had substantial “reserve orchards,” from Alberni and Bella Coola to the Kootenays. In 1909, in the Fraser Valley Tom Wilson reported 2,000 trees at Katz Landing and Ohamil, 1,000 at Matsqui, 500 at Tzeachten, and 400 at Skulkahyn. At Scowlitz, Wilson wrote, “The orchards are nearly all young, having been planted since 1896. Most of the old orchards were killed in 1894, during the flood of that year. The trees are very healthy and have been well planted.”[25] Wilson also noted that fruit grown by “the Penticton Indians” in 1910 “found a ready market at good prices,” and in 1912, “an Indian of my acquaintance sold 400 boxes of apples in Merritt.” The seller may have been Chief Tetlenitsa.[26]

Reports by Wilson and Smith, and by the McKenna-McBride commission, also show considerable Indigenous activity with vegetables and feed crops for commercial use. For example, in 1912, the 1,600 acres of the Kamloops Reserve generated 710 tons of hay, 105 tons of oats, and pease, 280 tons of potatoes, 80 tons of carrots, 15 tons of turnips, 6 tons of beans, and about 30 tons of other vegetables. With water, Smith reported, a total of 2,800 acres could be cultivated by the almost 100 households on the reserve.[27]

The Indigenous orchardists, farmers, and gardeners noted by Wilson and Smith complement and affirm Nancy Turner’s research: they exercised the right to use reserve land for agriculture and benefit personally in the process, they forbad people from using their gardens and orchards, and they passed on their rights of usage to successors.[28]

*

In Merritt in 1916 Tetlenitsa first offered his fruit “to the Stores.” Not getting the prices he wanted, he started to sell his fruit residence by residence. His store visits alerted the city’s merchants – and civic officials — to the presence of competition. As the city’s lawyer told Smith: “[Tetlenitsa] was interfering with the legitimate trade of the Merchants by selling his fruits to the Citizens of the Town; and in doing so he came under the head of Peddler.”[29]

Smith wrote for a “formal demand for a refund of … $25 extorted … from John Titlanatza….” He argued that both seizure and fine were illegal because Tetlenitsa as “a ward of the Federal Government is not subject to such a licence.”

The city clerk, Henry Priest, responded that council would keep the $25 until Smith showed city council the section of the Indian Act that released Indigenous persons from observing a municipal bylaw instituted by a provincial statute like the Municipal Act. The clerk encouraged Smith to consult Ottawa headquarters, “and let us know as early as possible the substance of their reply.”

Smith wrote Ottawa with copies of this correspondence. He also reported the opinion of the Merritt city solicitor that under the Municipal Act, Merritt could licence commercial activities that occurred within city limits and prohibit Tetlenitsa’s door-to-door activities.

Smith informed his superiors that the impoundment, if allowed to set a precedent, would “practically debar the Indians from disposing of their produce, whether it be hay, grain, vegetables or fruits in any of the Incorporated Cities in this Province.” He added that, “If every Indian has to pay a license to sell his produce in Incorporated Cities they will surely starve.”

A week later, the DIA’s secretary responded that, in the department’s opinion, the department’s Indigenous “wards” were indeed “…amenable to the by-laws of a municipality.” He encouraged Smith to ask city council to return the $25 “as an act of grace,” and he promised to write to the Merritt council. While thus throwing Tetlenitsa and Smith to the wolves, the secretary also sidestepped the issue of privation and starvation resulting from the potential need to purchase multiple municipal licences.

The DIA’s deputy superintendent general, Duncan Campbell Scott,[30] entered the fray and wrote directly to the Merritt council. He accepted that the DIA’s “Indian” wards were not exempt from provincial statute, but he added that:

[L]eniency has almost invariably been shown to the Indians by assistance being given them to secure their livelihood by their own industry. By reason of this leniency the Indians have … come to the conclusion that they are entitled to special privileges in regard to these matters. This being the case Titlanetza would no doubt conclude that he was within his rights in peddling the fruit grown by him.

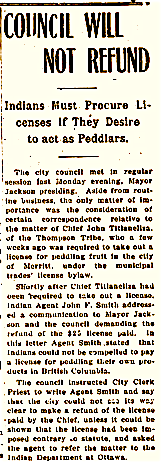

The Merritt Herald, on October 6, published the contents of Scott’s letter to council under the headline “COUNCIL WILL NOT REFUND: Indians must procure licences if they desire to act as pedlars.”

Indigenous residents of the Nicola Valley responded to publication of Scott’s letter by holding “an indignation meeting” on October 9 in Spences Bridge. They wanted the DIA to amend the (federal) Indian Act to release them from the municipal fees imposed under provincial legislation.

Scott wrote again to Merritt council on October 31, again requesting leniency. Henry Priest, the city clerk, responded that council would not refund the $25, and indeed had decided to double the cost of a licence. Priest added, somewhat vindictively, that:

The Indian in question is not in need of a refund and would simply laugh at the City and snap his fingers if he got it — his operations are by the car load and seriously interfere with the Merchants here. The Merchants are paying high taxes and are in legitimate business to make a living …. if [this] were a case of a poor ignorant native [council] would rather give than take away…, but Chief Titlanetza is not by any means in need of charity.

Agent Smith, on receipt of a copy of Priest’s letter, told Ottawa that Tetlenitsa had not distributed a boxcar load of fruit. He had taken seventy boxes of apples and twenty of plums by wagon to Merritt.

And then he made an astute observation about the political economy of Merritt: “[T]he overhead maintenance charges of the City of Merritt are very considerably maintained from money extorted from Indians in fines and other methods.” He argued that fines imposed for minor offences on Indigenous people in Merritt by city police court magistrates became city money. Fines paid by the owners of Native horses impounded by city authorities because they were running loose also benefited the city coffers. Smith argued, in effect, that a variety of fines on Indigenous people helped subsidize the town’s infrastructure.

Tetlenitsa’s troubles with the chief constable at Merritt in 1916 are a startling example of the unforeseen practical consequences of local bureaucratic decisions on Indigenous people, who were technically governed by federal laws. Tetlenitsa’s travails at Merritt also demonstrate three British Columbia political continuities. The first is the intimate relationship between farmers and government agencies. The second is the ability and propensity of a subordinate and derivative level of authority to trouble the work and deny the ambitions of a principal authority. The third is the contested quality of residence between Indigenous people and settlers in the human geography of the place we call British Columbia.

Chief Tetlenitsa’s experience with Merritt town council in 1916 shows an individual doing what a federal authority wanted and encouraged, while incurring the legal action of a municipal authority to stop him from filling those wishes. John Tetlenitsa and John Smith did poorly by DIA headquarters; Merritt’s city council and merchants did well.

Posterity has been kinder to Tetlenitsa than the officious penny-pinching burghers of Merritt. The Chief Tetlenitsa Memorial Outdoor Theatre at the confluence of the Nicola and Thompson rivers is one pointer to John Tetlenitsa’s consequential life.

Opening of Tetlenitsa Memorial Theatre at Cooks Ferry Reserve at confluence of Thompson and Nicola Rivers, 2010

*

[1] Nancy Turner et al., Thompson Ethnobotany: Knowledge and Usage of Plants by the Thompson Indians of British Columbia (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 1990), 262.

[2] John F. Smith to The Asst. Deputy and Secretary, Department of Indian Affairs, Ottawa, 13 Sept’ember 1916, Library and Archives Canada, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs central registry folder, “Kamloops [Agency] — Pedlar’s Licence for Indians Selling Their Produce.” ONLINE. This episode has hitherto not been the subject of scholarly analysis.

[3] Smith to the Asst. Deputy, 22 November 1916, in “Pedlar’s Licence for Indians Selling Their Produce.”

[4] John F. Smith to The Asst. Deputy and Secretary, Department of Indian Affairs, Ottawa, 13 September 1916.

[5] In the fullness of his years John Fremont (or Freemont) Smith was a raconteur. He died in 1934, on the same day he filed, with the Kamloops Sentinel newspaper, a report on the early settlement of the Thompson countryside. The Kamloops Museum and Archives has published, on the city’s webpage, a two-page, typewritten biography, “John Fremont Smith.” Trefor Smith, “John Freemont Smith and Indian administration in the Kamloops Agency, 1912-1923,“ Native Studies Review 10: 2 (1995), is a scholarly account of Smith’s administration. Both are online.

[6] “Cleansing Indian orchards” was the originating purpose of the campaign: Library and Archives Canada, Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended March 31 1907, II, “Appropriation Accounts,” 175. ONLINE.

[7] “Annual and Quarterly Meetings of the British Columbia Fruit Growers’ Association,” January 1905- February 1906, G13. ONLINE.

[8] Ibid.

[9] HBC horticulture west of the Rockies started in the 1820s. See James R. Gibson, Farming the Frontier: The Agriculture Opening of the Oregon Country 1786-1846 (UBC Press, 1985). For an even earlier horticultural tradition, see William Dunmire, Gardens of New Spain: How Mediterranean Plants and Foods Changed America, 2004. ONLINE.

[10] Turner’s two-volume Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America, 2014, is a monument to more than forty years of inquiry and summary in the field and the archives. Scholarship on historic Indigenous farmers includes Rolf Knight, Indians at Work: An Informal History of Native Labour in British Columbia 1858-1930 (1978); James Burrows, “ ‘A Much-Needed Class of Labour:’ The Economy and Income of the Southern Interior Plateau Indians, 1897-1910,” BC Studies, August 1986; John Lutz, “After the Fur Trade: The Aboriginal Labouring Class of British Columbia, 1849-1890,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 1992; and Duane Thomson, “The Response of Okanagan Indians to European Settlement,” BC Studies (Spring 1994). See also Amber Kostuchenko, “The Unique experiences of Stó:lō farmers: An Investigation into Native Agriculture in British Columbia, 1875-1916,” 2000. All are online.

[11] See Cole Harris, Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance and Reserves in British Columbia (UBC Press, 2002).

[12] The Merritt Coalfield surrendered up 2.4 million tonnes of coal between 1906 and 1963, mostly through underground mining. See British Columbia Ministry of Mines and Energy, “Merritt Coalfield,” 2004. ONLINE.

[13] The Merritt Drill Hall opened in February 1915. The Adelphi, Coldwater, and Grand hotels were all built in the years immediately before the Great War. Wesley Methodist, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian, St. Michael’s Anglican, and Sacred Heart Catholic were the churches. The newspapers were today’s Merritt Herald predecessor and The Nicola Valley News. The latter ceased publication in 1916: UBC, British Columbia Historical Newspapers website.

[14] On Teit, see Wendy Wickwire, “TEIT, JAMES ALEXANDER,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 18, 2017:

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/teit_james_alexander_1884_15E.html.

[15] LAC has published its “petitions” folder of Kamloops and Kamloops-Okanagan Indian Agency correspondence on its website. The deliberations and decisions of the Indian Affairs royal commission, and transcripts of the 1910 memorial and the 1916 deputation, are available on the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs website.

[16] Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, Our Hearts are Bleeding, Royal Commission on Indians Affairs for the Province of British Columbia, “November 3 1913, Meeting with the Indians of the Cook’s Ferry Tribe….” ONLINE.

[17] Royal Commission on Indian Affairs, “Evidence given [at Victoria] by Mr. J.F. Smith, Indian agent, Kamloops, B.C. … November 19th and 20th, 1913.” ONLINE.

[18] “Meeting with the Indians of the Cook’s Ferry Tribe….”

[19] R.C. Treherne, “In Memoriam Tom Wilson,” Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia 10, 1918, 30-31. ONLINE.

[20] David Dendy, “Tom Wilson President, 1899/1900,” A Fruitful Century, 1989. ONLINE.

[21] The other tree-fruit geographies on this continent are in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Washington state (two), Oregon state (two), and California.

[22] Wilson’s entomological work is memorialized in a chapter in Paul Riegert, From Arsenic to DDT: A History of Entomology in Western Canada (1980), and in an entry in Entomologists of British Columbia (1991).

[23] See, for example, See, for example, David Mitchell and Dennis Duffy, eds, Bright Sunshine and a Brand New Country: Recollections of the Okanagan Valley 1890-1914 (Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Archives, 1979).

[24] See, for example, UBC Library Open Collections, BC Sessional Papers, “Annual and Quarterly Meetings of the British Columbia Fruit Growers’ Association,” January, 1905 to February, 1906. ONLINE.

[25] Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended March 31 1910, I, 255-256.

[26] . . . Year Ended March 31 1916, 114; . . . March 31 1915, 116; . . . March 31 1914, 106; . . . March 31 1913, 289; . . . March 31 1910, 258, and . . . March 31 1911, 276.

[27] . . . Year Ended March 31 1913, 289.

[28] Usufructory conventions existed among the Indigenous peoples of the west coast since time out of mind. See Nancy Turner, Robin Smith, James Jones, “A Fine Line between Two Nations: Ownership Patterns for Plant Resources among Northwest Coast Indigenous Peoples,” in Douglas Deur and Nancy Turner, Keeping It Living, 2006.

[29] The following discussion is based on John F. Smith to The Asst. Deputy and Secretary, Department of Indian Affairs, Ottawa, 13 September 1916 and 22 November 1916, Library and Archives Canada, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs central registry folder, “Kamloops [Agency] — Pedlar’s Licence for Indians Selling Their Produce.” ONLINE.

[30] On Scott, see Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1986).

*

Michael Sasges is a retired Vancouver newspaper editor and reporter, and grandfather. He first came across the story of John Tetlenitsa and John Fremont Smith while preparing “Colliers and Cowboys: Imagining the Industrialization of British Columbia’s Nicola Valley,” a research project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies at Simon Fraser University, in 2013. He acknowledges, with thanks, the “your newsroom days are over” observations of two anonymous readers asked by BC Studies to read an earlier version of this story.

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Leave a Reply