Finding Franklin, nailing Harper

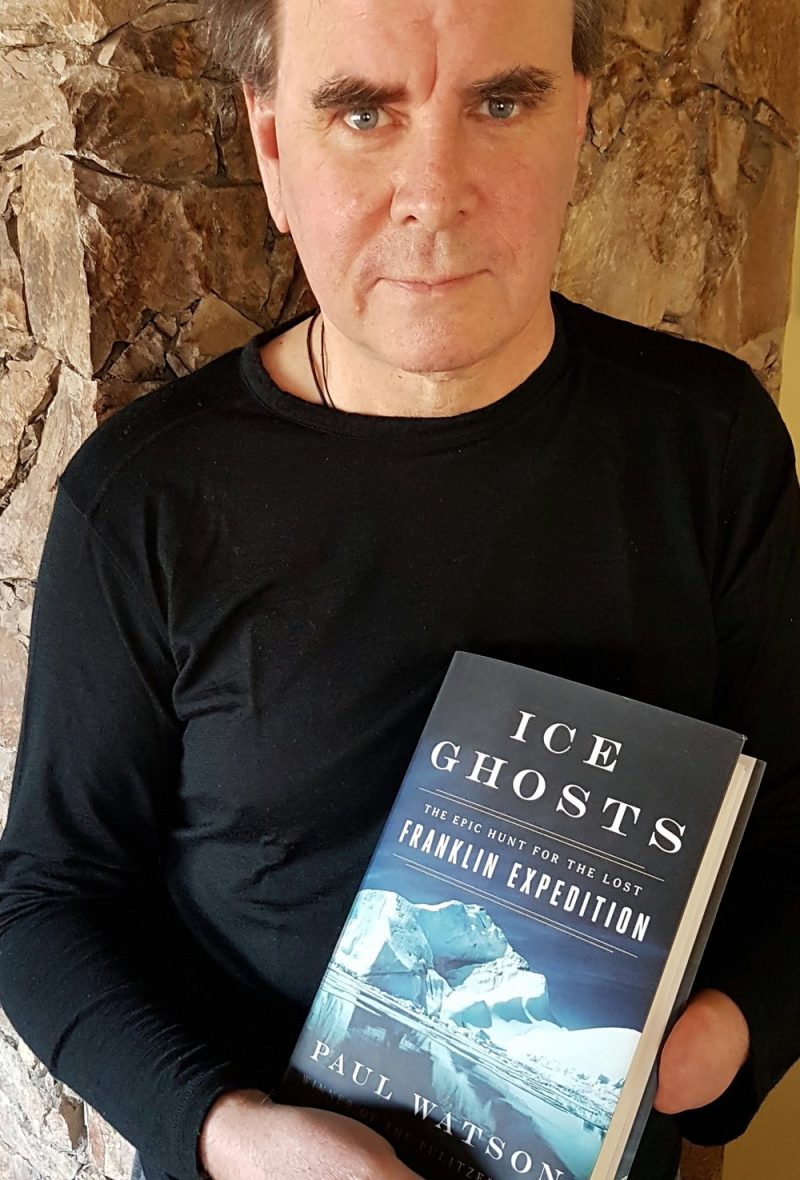

Paul Watson's book on the Franklin Expedition is cited as one of the top six science books of 2017 by The Guardian.

May 17th, 2018

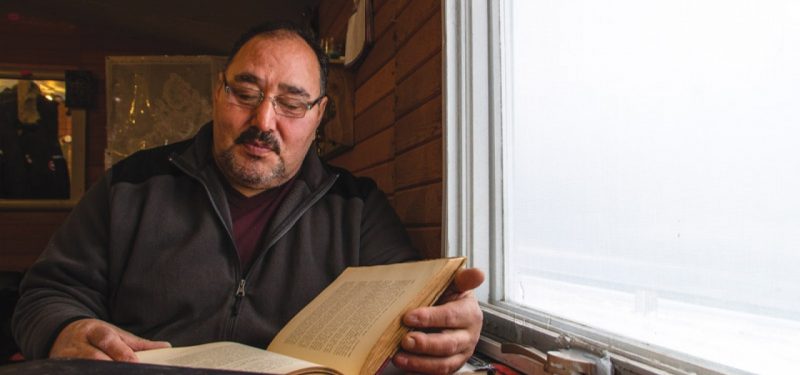

Inuit Sammy Kogvik of Canadian Ranger Patrol Group pinpoints fates of Franklin's ships.

While covering the Franklin story, the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist got sacked for blowing the whistle on Prime Minister Harper’s shenanigans.

Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition

by Paul Watson

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2017.

$34.95 / 9780771096525

Reviewed by Walter O. Volovsek

*

Based in Coquitlam, B.C., the remarkable Paul Watson–not to confused with that Sea Shepherd captain also named Paul Watson who regards Greenpeace as too timid–is now South Asia bureau chief for the The Los Angeles Times.

Based in Coquitlam, B.C., the remarkable Paul Watson–not to confused with that Sea Shepherd captain also named Paul Watson who regards Greenpeace as too timid–is now South Asia bureau chief for the The Los Angeles Times.

Previously, Watson won the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for photography. Recently he was shortlisted for the 2017 Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize (BC Book Prizes) for Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition. It was also named one of the top six science books of 2017 by The Guardian,[1] likely a unique achievement for a B.C. author.

Ice Ghosts comes with some controversy attached. In July 2015, Watson quit the Toronto Star when the paper quashed his story of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s attempt to use the discovery of Sir John Franklin’s ship HMS Erebus for political propaganda.

According to The Globe and Mail, (July 8, 2015), “Mr. Watson told The Globe he and others were disturbed by the way the announcement of the Franklin ship’s discovery last September was stage-managed by the Prime Minister’s Office.”

“Ice Ghosts is a fascinating addition to the Franklin Record,” according to Walter Volovsek, who previously reviewed Owen Beattie and John Geiger’s Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2017) for this periodical. – Ed.

*

After I agreed to review Paul Watson’s Ice Ghosts I was expecting to work my way through much of the material I had been exposed to before. When the book arrived, I was pleasantly surprised. Although a repetition of previously published facts is unavoidable, enough new material is injected to capture the attention of even the most seasoned Franklin scholar.

For me the biggest novelty was the introduction of much fascinating material quoted directly from the written record produced by James Fitzjames, captain and later commander of Franklin’s flagship, HMS Erebus. His notes of memorable events and his character sketches of his unfortunate companions almost put us aboard the doomed vessels. Like I did, Paul Watson entered into a discussion with William Battersby, his biographer.

The information Fitzjames left behind survived him as he sent his remarkable record to his adoptive family on the last support ship, which turned homeward off the coast of Greenland as Franklin’s flotilla rushed toward Lancaster Sound. What a record he would have left, had not the remainder of his writing been lost to the elements!

He did of course leave us two more written records, in metal cylinders deposited in two conspicuous cairns on the northwest coast of King William Island. He had prepared these aboard the Erebus in late May 1847 and entrusted them to a small reconnaissance party, headed by Lt. Graham Gore, for placement on the island. The most northerly of these was retrieved eleven months later, so the note could be updated, and placed in a new cairn at Victory Point.

I have scrutinized this record as well as the published analysis of both surviving records by Richard J. Cyriax. I have come to the conclusion that Cyriax missed one important detail, which changes the interpretation of Franklin’s movements. The first letter following the Beechey Island coordinates (with the wrong date), as written by Fitzjames, is a capital A, making what follows a new sentence; that tells us the circumnavigation of Cornwallis Island was the first action accomplished the following fateful year (1846). The grammatical structure used in the Gore Point record makes this more obvious.[2]

Watson is wrong in attributing the entire initial entry to Gore & DesVoeux, as the only writing Cyriax attributes to them are their signatures.

I like Watson’s linkage between Sir John Franklin and his would-be saviour, Sir John Ross. Both had suffered the indignities of character assassination and were driven by the impulse to redeem themselves in the public eye.

Franklin set himself up by his efforts to govern Van Diemen’s Land more humanely; Ross would be ridiculed for the rest of his life for imagining Croker Mountains across Lancaster Sound, the main gateway to the Northwest Passage. Franklin was literally pushed into his last action by his wife, who trembled at the prospect of being socially sidelined. Ross promised to bail the old man out, and he tried to fulfil his promise in spite of continual disinterest from the Admiralty.

It fell to Lady Franklin to keep agitating for a rescue. In desperation, she turned to the occult, and obtained some surprising results. The location of the stranded ships and the deserting crews was pinpointed quite accurately by a ghost toddler (Weesy Coppin) as well as an abused boy who grew to a scarred manhood with supernatural powers (W.P. Snow). But unfortunately the searches that did come were focused north of Lancaster Sound, in the belief Franklin had come to grief in his search for the Open Polar Sea.

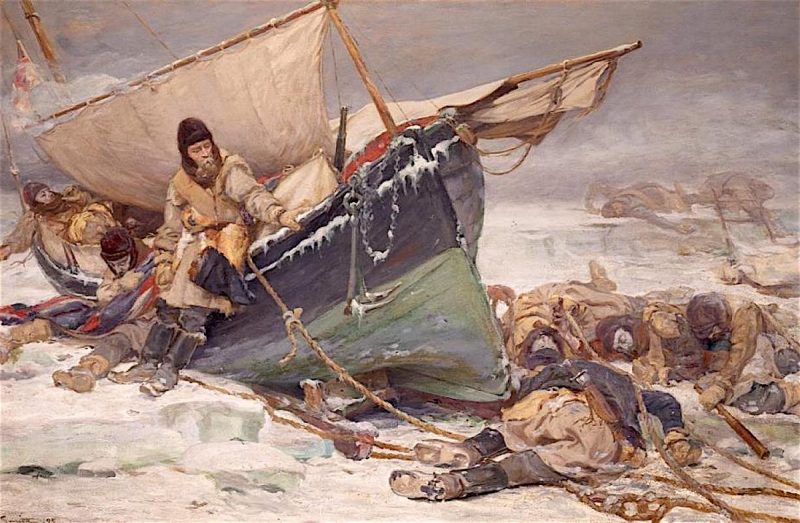

When news finally arrived from Dr. John Rae in the form of salvaged relics and stories obtained from the Inuit, the information was shattering to Victorian sensibilities. A suggestion of cannibalism drew forth the ire of Charles Dickens, who painted an image of lying and mean-spirited natives.

Rae was criticized for not following up on the Inuit stories and checking out the area himself. The season was wrong, he pointed out, as snow covered any evidence; but there was a more disturbing reason that he failed to fathom. The Inuit considered the area cursed by evil ghosts, which would be merciless with trespassers into the forbidden zone. Stories of later intruders who came to grief for not respecting the curse are sprinkled throughout the book.

The work is graced by many other tidbits of fascinating information. The operation of Stephen Goldner’s meat canning operation is exposed. Set in backward Moldavia, where underpaid workers could be bullied and beaten and raw supplies were cheap, the business made a good profit, especially as it also specialized in tallow and hides.

Employee resentment led to poor quality control and probably some outright sabotage. Complaints about spoilage and inclusion of waste products were frequent, but Goldner’s price was attractive. Tainted canned food was a major contributing factor to the disaster.

Other intriguing features include excellent descriptions of Franklin’s ships and details of items like desalinators, light shafts, the modified steam locomotives and their retractable propulsion gear. The intriguing semaphore communication system between Admiralty headquarters and coastal points is explained. The collapsible Halkett boat, which converted to a packsack, was described by Inuit eyewitnesses precisely, giving credence to their testimony. A lot of emphasis is placed on the Navy clothing that was totally unsuited to the Arctic.

The hard life of the Inuit is presented, and we learn to respect the difficult choices they had to make and the spiritual beliefs that grew out of that harsh lifestyle. The most memorable statement that sums those up is: “If you must see to know, you will miss many things that are real.” New revelations are presented about interpreting native maps and their terms of reference to the landscape they are describing. Watson’s vivid lyrical description of an Arctic winter brought me back to Cassiar, where I sampled –40 degree temperatures as a child.

In the final section the author shifts his attention to previously written-off Inuit testimony, which led to the discovery of the ships. Key personalities in establishing a database that was to prove so fruitful were an Inuit who could remember stories his great grandmother had told him, and a retired BC Ferries captain. Louie Kamookak devoted his life to searching out elders to mine and interpret the Inuit oral memory.

A key contribution came from David Woodman, who devoted himself to seeking out and analyzing the published record of Inuit recollections, as recorded by the various searchers who had come in contact with eyewitnesses to the tragedy. His published work refocused the attention of many.[3]

Fittingly enough, HMS Erebus was located on September 2, 2014 in 36 feet of water exactly where the collective Inuit memory had placed it prior to sinking: a couple of miles from the small island the Inuit had named Kivevok, translated as Where it Sank.

The discovery of HMS Terror was even more amazing. Sammy Kogvik was taken on as the final crewmember for the R/V Martin Bergmann, a vessel funded by Research in Motion cofounder Jim Balsillie. On their journey along the coast of King William Island on September 2, 2016, Kogvik confided to the crew his snowmobiling experience nearly a decade earlier. He and a friend were astonished by the sight of what appeared to be a mast in the ice of Terror Bay.

That story was intriguing enough for the crew to immediately divert their attention to the now open water of the bay. Before the day was over, they located the wreck in 79 feet of water. Unlike Erebus, the smaller ship was almost perfectly preserved.

It seems fitting that the second discovery was funded by private enterprise, as many scientists had been ticked off by the former Harper Government for muzzling them. Martin Bergmann, who was in charge of operations at Resolute, was uncomfortable with the government taking all the credit for the work being done in the Franklin searches. He got Peter Mansbridge involved in documenting the search effort, and Peter drew in Balsillie. The ship now honoured Bergmann’s memory. He was killed on August 20, 2011 as First Air flight 6560 crashed on its approach to Resolute.

The Terror discovery makes a new scenario much more plausible. As Woodman pointed out, it would not have been possible for the ship to enter Terror Bay by drift alone, as the prevailing current was southward. It is highly likely both ships were manned by returning parties, and moved southward with the assistance of opening waters and natural forces. Inuit testimony confirms that scenario.

There is more than Inuit history to support the contention the abandoned ships were reoccupied during the summer of 1848. The best evidence is provided by the well-organized grave of Lt. John Irving, who was involved in demolishing the northern cairn in search of the document deposited by Gore, as the party was leaving on their southward trek. Lt. Hobson later found his broken pickaxe and a discarded canister at the site. Irving was very much alive then, and must have succumbed after his return to the ships. His remains made it home to Edinburgh.

Also, the boat with the skeletons was found considerably south of Collinson Inlet, and must have been turned around for a return journey to the ships by the dissenting group. Inuit memory has the boat being dragged southward near Terror Bay, and its final resting place was well to the north of that spot.

With all its new tidbits of information and the insertion of new personalities into the Franklin saga, Ice Ghosts is a fascinating addition to the Franklin Record. Its faults are few. I mentioned the problem with the Victory Point Record. The only other complaint I can offer is that the maps, which are otherwise excellent, are a bit annoying as they could have named many other geographical features that the text refers to. But those are small blemishes in a valiant literary effort by a seasoned journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner.

*

After studying medicine and managing the biology labs at Selkirk College for 24 years, Walter O. Volovsek retired to a second voluntary career: developing walking and ski touring trails for the Castlegar community. Most of these are also presented to the user as conduits into the past by means of interpretive signage and related essays on his website www.trailsintime.org. This led to connections with descendants of important Castlegar pioneers, and in 2012 Walter self-published his biography of Castlegar founder Edward Mahon, The Green Necklace: The Vision Quest of Edward Mahon (Otmar Publishing, 2012). Mahon was also known for his legacy of parks and greenways in North Vancouver. Walter has also written a book on his trail-building efforts, Trails in Time: Reflections (Otmar, 2012), and has been commissioned to develop signs in key locations including Castlegar Millennium Park, Castlegar Spirit Square, and Brilliant Bridge Regional Park. Walter currently writes a history column for the Castlegar News.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/dec/03/robin-mckie-best-science-books-of-2017-caesar-last-breath-vaccine-race-dava-sobel-glass-universe

[2] See my detailed comments on this and my explanation of the puzzling entry on the cairns in my review of Owen Beattie and John Geiger, Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2017): https://bcbooklook.com/2017/12/18/starvation-cove-terror-bay/

[3] See David Woodman, Unravelling the Franklin Mystery: Inuit Testimony (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1991).

Leave a Reply