Fighting for the right to read books

The struggle for civil rights in 1960's America included the right to read books as many public libraries in the South barred African Americans, even though it was illegal.

November 28th, 2019

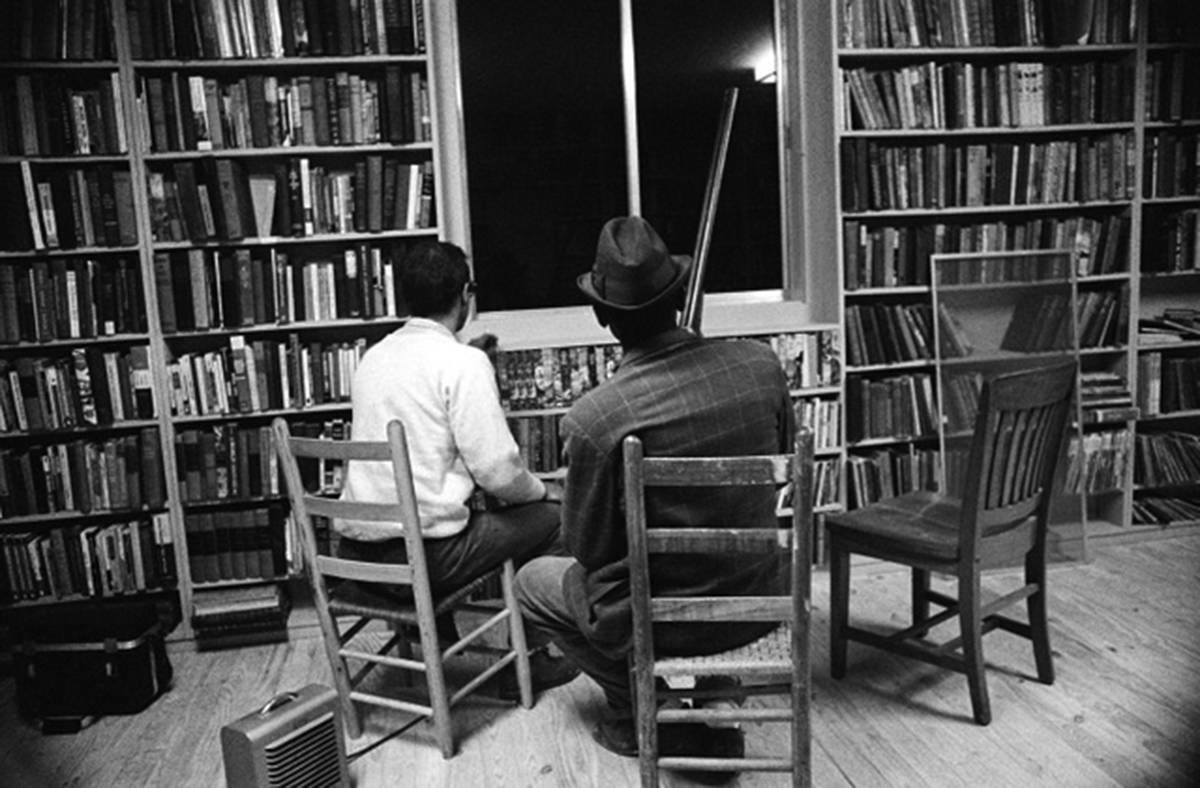

Albemarle, NC Regional Library Bookmobile, often referred to as a fugitive library. Circa 1960s

In response, African Americans began creating “Freedom Libraries” and over 80 appeared in the deep south as documented by B.C. librarian and author, Mike Selby.

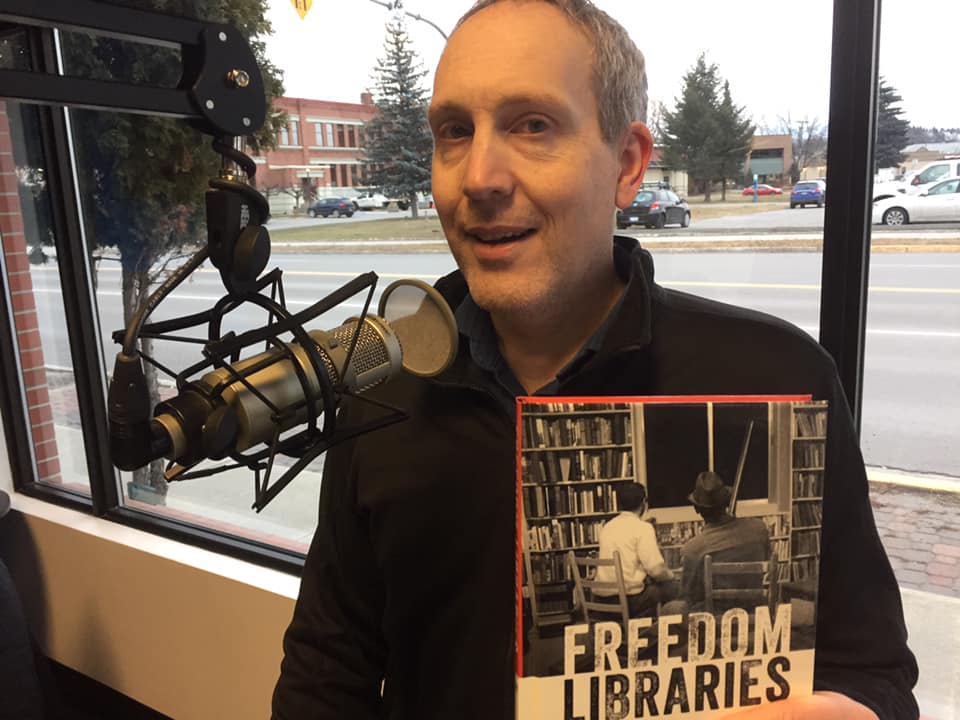

Freedom Libraries: The Untold Story of Libraries for African Americans in the South (Rowman & Littlefield $36)

Librarians not only help readers find books, some also write them. Cranbrook Public Library’s community development librarian is the latter. He has written Freedom Libraries: The Untold Story of Libraries for African Americans in the South about the period in the mid-20th century when public libraries were not immune to racial segregation practices in the U.S., even though it was illegal.

Many libraries were desegregated on paper only: there would be no cards given to African Americans, no books for African Americans to read, and no furniture for them to use. Under these conditions, ‘Freedom Libraries’ began to evolve, installed by civil rights movement people who also called for book donations, which came from all over the country.

These parallel libraries appeared in the deep South, staffed by civil rights voter registration workers. They varied in size and quality but all of them created the first encounter many African-Americans had with a library. Terror, bombings, and eventually murder would be visited on freedom libraries – with people giving up their lives so others could read a library book. -Ed.

*

Mileston, MS summer volunteer carpenter, Jim Boebel and a local resident post a shotgun watch at the community center against a fire bomb threat by local whites. Threats were common that summer and local men took turns guarding the Freedom Library every night.

When he was ten, Mike Selby’s father took him to see Star Wars at his hometown’s local cinema. He remembers so many townspeople turned out that the police had to barricade traffic from the street. But everyone got in to see the movie and, with his father, Selby felt safe and warm and that he belonged. He also recalls feeling an “absolute sense of wonder” that night.

He wouldn’t feel that way again until 35 years later when he stood outside the University of Alabama’s Foster Auditorium on his first day of library school. As fortunate as he was, Selby was all too aware of the completely different experience another student had fifty years before. He recounts that episode and how it changed him in his preface to Freedom Libraries, reprinted below with permission of the author.

“My feet were on sacred ground, as fifty years earlier before me another student stood here on her first day of library school. Her name was Autherine Lucy, and – due to a variance of pigmentation in her skin – her presence ignited one of the worst race riots in the history of the state. The same scenario played out seven years later, when two more students – Vivian Malone and James Hood – were refused entry by Alabama’s governor at the time and a wall of state troopers. Standing there in the oppressive August heat (the massive willow oak trees gave no shade), I took in the names of all three, now etched in the memorial that bears their name. For the second time in my life, the profound sense of sheer wonder rushed through me. Reaching out for Lucy’s name reproduced the feelings I had so exactly when I was ten that I almost turned looking for my father’s hand.

The night he took me to Star Wars, there was simply no chance of either of us being turned away at the ticket booth. There were no back entrances, special seating, or separate washrooms to degrade us. No one would beat my father with a bat or chain, and no policeman would use a cattle-prod on me. My sisters would not be tormented at their school. My mother would not lose her job. No one would shoot at our cars, dynamite our home, or run us out of town. In fact, no one in the community had any fear of being beaten within an inch of their life, or branded, or lynched, or castrated.

This was not the reality for millions of African Americans. Change the theater to anything – grocery store, diner, school, playground, beach, or even a library – and the complete lack of human empathy is as staggering as the unimaginable levels of courage displayed by those who sought to change it.

Autherine Lucy never became a librarian, but a New York Post reporter who saw her try wrote, ‘What is this extraordinary resource of this otherwise unhappy country that it breeds such dignity in its victims.’ He ‘watched in awe’ as she barely left the campus alive that day. I felt that same awe decades later, standing where she stood.

This book is dedicated to Autherine Lucy, who was denied her life’s promise. At great personal cost, she opened the doors for so many others. I think of her often in my career and try to honor her as I practice librarianship.”

*

B.C.-born and raised Selby is also a newspaper columnist in addition to being a librarian and author. He received his MLIS from the University of Alabama, which is where he first unearthed the story of the Freedom Libraries.

Leave a Reply