Empathetic profiles of Kootenay lives

In the West Kootenays, many people have overcome trauma by finding solace in the land.

September 09th, 2018

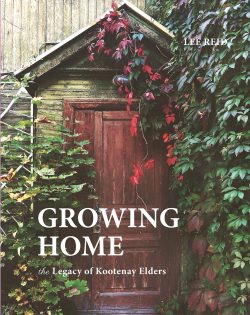

Lee Reid pays tribute to the "artistry of living" in the West Kootenays. Don Bodger photo.

Seventeen people profiled in Lee Reid’s Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders include author Tom Wayman, plus Doukhobors Ellie Lazareff, and Pete and Shirley Relkoff.

Growing Home: the Legacy of Kootenay Elders

by Lee Reid

Nelson: Growing Home Elders Press, 2017.

$26.95 / 9780995816404

Reviewed by Duff Sutherland

*

In Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders, Lee Reid profiles seventeen men and women, born between the 1920s and 1950s, who made their lives in the West Kootenay. Reviewer Duff Sutherland of Selkirk College finds a combination of paid employment and subsistence agriculture running through most of these West Kootenay lives. “Most of Reid’s interviewees report that they share their produce with their neighbours and with the broader community to create a level of food security in the region.” — Ed.

*

Growing up in postwar Canada, Lee Reid “saw nothing good of aging.” Her war veteran father died young and her young, attractive mother moved to Canada where she remarried a veteran who struggled with alcohol. Reid’s childhood and early adult experience of bars, hotel parking lots, and the Legion offered her a harsh view of aging. According to Reid, members of her mother’s generation, who looked sickly by the time they reached their forties and fifties, rarely discussed death.

Growing up in postwar Canada, Lee Reid “saw nothing good of aging.” Her war veteran father died young and her young, attractive mother moved to Canada where she remarried a veteran who struggled with alcohol. Reid’s childhood and early adult experience of bars, hotel parking lots, and the Legion offered her a harsh view of aging. According to Reid, members of her mother’s generation, who looked sickly by the time they reached their forties and fifties, rarely discussed death.

Reid never forgot her experience of the struggles of Canada’s wartime generation. In response, in her retirement, she sought out people whose lives she felt represented a positive response to growing old. In Growing Home: the Legacy of Kootenay Elders, Reid introduces us to seventeen individuals (several make up couples) who have made their lives in the West Kootenay region of British Columbia. While they come from a variety of backgrounds, most of the individuals and couples in Growing Home, grow their own food and work their own land. Reid’s well-written and empathic profiles are beautifully presented with photographs and drawings. In Growing Home, we meet people whose lives suggest ways to live. Their diverse histories and experiences also offer rich material on the social history of the West Kootenay.

Growing Home effectively evokes the longstanding, passionate response of European settlers to the rugged lands and environment of the West Kootenay. Nelson businessman George Coletti, whose family came from central Italy in the early twentieth century, discusses the network of families that dominated the city in its early years while also describing his love for the Kootenay wilderness and for his family property on Kootenay Lake.

Coletti also describes a history of Euro-Canadian racism towards Italians, Chinese, Japanese and indigenous peoples in the region. He concludes: “Some say the Chinese were pushed out of Nelson, same as the Japanese and the native Indian population. A lot of them died here from poor living conditions, or moved to the coast where the Chinese culture welcomed them. I liked and respected them….” (p. 41).

Ellie Lazareff and Pete and Shirley Relkoff, on the other hand, recount their Doukhobor family histories in the West Kootenay that also reach back to the early twentieth century. Ellie Lazareff, a beloved grandmother of a large family, lives on a beautiful property she built with her husband Jim near Castlegar. The Relkoffs farm in the Slocan Valley. Pete Relkoff evokes the Doukhobors’ reverence for the land and the “living spirit” in each person while also describing the troubled history of the religious community in the West Kootenay.

In the early 1950s, the provincial government apprehended eight-year-old Shirley Relkoff along with 200 other Doukhobor children whose families were members of the radical Sons of Freedom community. The government held the children in a residential school in New Denver as part of its policy of forced assimilation. Shirley notes, “We were allowed to see our families for one hour, every two weeks, and only on the other side of a chain link fence. We could reach through with our hands, to touch our parents, but they could not come further for many reasons….” (p. 103). Relkoff only told her story publicly for the first time at a storytelling event in 2012.

Many of Reid’s other subjects survived traumatic personal experiences in their lives. Like Ellie Lazareff and Pete and Shirley Relkoff, they find solace in their connection to their land, and in family and community. It is striking that those groups that lost most or all of their land in the region such as Indigenous people, the Chinese market gardeners, and the Japanese-Canadian internees, are almost entirely absent from Reid’s book and from much of West Kootenay history.

The lives of Reid’s subjects, who are mostly in their sixties and seventies, also reveal the effects of the postwar economic boom on the region. Capital’s intensive exploitation of resources along with the state’s expansion of infrastructure and services led to a boom that had a profound effect on the people and the land. May Hori describes her family’s experience of being interned by the government. Her family lost its Maple Ridge farm and spent the war in an internment camp at Lemon Creek in the Slocan Valley. Her father made the difficult choice after the war to take his family to Japan, a country that May did not know. Hori eventually returned to the West Kootenay in the early 1950s where she found long-term work as a cook and married Masao Hori who had a building business in New Denver.

Ron McIntyre of Blueberry, a dedicated beekeeper, had a long, distinguished career as a skilled worker at the booming smelter in Trail. The famous Kaslo bakers, Fred and Liane Rudolph, came to the region in response to the Canadian government’s postwar campaign to recruit skilled European labour. Others like Helen Jameson, Anna Thyer, and Milt and Donna Goddard arrived from elsewhere to purchase land in the 1960s. They all worked hard on their properties to raise their families while often relying on income from careers as professionals and government service workers.

By the 1960s and 1970s, improved infrastructure, expanding services, and public awareness in other parts of North America of the beauty of the remote valleys of region brought more people who sought lives close to the land. Pat Morrison, a midwife, nurse, and teacher, and, Moonbow (aka Jim Rutkowsky), a Vietnam War era conscientious objector and now an organic farmer, came as part of the wave of American migration to the West Kootenay that began after the mid-1960s. More recently, the writer Tom Wayman and Victoria and Steven Mounteer made homes and developed land in the Slocan Valley.

Reid’s profiles of these recent arrivals describe individuals and a couple who made important contributions while developing knowledge of the land and environment of the region. At the same time, their experiences reflect a broader pattern that since the 1930s very few people have made their living entirely from the land in the West Kootenay. As in other of Canada’s regional resource economies, in the West Kootenay, economic and social factors have long led people to combine subsistence agriculture with paid employment. However, most of Reid’s interviewees report that they share their produce with their neighbours and with the broader community to create a level of food security in the region.

The current focus on living with “intention” and being “present” suggest the limits to the control we have over our lives in an era of accelerating globalisation. The members of Reid’s mother’s generation may have experienced a similar lack of control over their lives during the war and its aftermath. In the profiles in Growing Home, we encounter people who have made considerable achievements while suffering the hardships and losses of poverty, internment, the death of spouses and of children, and the breakdown of marriages. They also reflect on other challenges that come with growing old such as loneliness and illness.

We meet thoughtful people who are grateful for their lives, families, and communities. In Reid’s terms, they have “grown” homes, and have learned, over the long haul, the “artistry of living” (p. 175). Reid suggests that we see some of this artistry in their approaches to life; we see other evidence of it in the photographs of their homes and gardens and, at the end of each chapter, in their advice and recipes. In Growing Home, Lee Reid nicely presents the life stories of these interesting people that reveal some of the social history of the West Kootenay. We are lucky to have met them.

*

Duff Sutherland has just, in September 2018, begun his 25th year of teaching undergraduate history courses. For the past eighteen of those years, he has taught at Selkirk College at Castlegar. One of the courses he teaches is “A History of the West Kootenay.” As well as many book reviews, Duff has published articles on Newfoundland labour history and the relations between settlers and Indigenous peoples in the West Kootenay. He is currently writing about loggers and their unions in the East Kootenay during the 1920s.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.

Leave a Reply