Emotional time bombs

"Hope floats like so much dandelion fluff and tragedy ensues," writes Caroline Woodward, responding to The Promise of Water by Judy LeBlanc.

April 26th, 2018

Judy LeBlanc, artistic director of the popular Fat Oyster Reading Series.

“This is a terrific debut and a book to reread just to admire the use of the language and to spend more time with some classic Vancouver Island characters.”

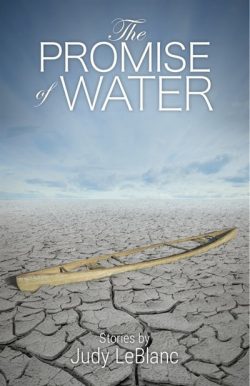

The Promise of Water

by Judy LeBlanc

(Oolichan: 2017)

978-0-88982-320-4 $19.95 tp

Review by Caroline Woodward

*

Judy LeBlanc’s debut collection evokes a tangible sense of place—Vancouver Island—where the sweet fragrance of cedar mingles with the murky odours of damp mould and stale cigarette smoke can be washed away by a clean, cold blast of salt air. It is populated with fully-imagined lives, allowing us to gain insight and even feel compassion for humanity’s blundering ways.

Judy LeBlanc’s debut collection evokes a tangible sense of place—Vancouver Island—where the sweet fragrance of cedar mingles with the murky odours of damp mould and stale cigarette smoke can be washed away by a clean, cold blast of salt air. It is populated with fully-imagined lives, allowing us to gain insight and even feel compassion for humanity’s blundering ways.

Each story has what I call an ‘emotional time bomb’ within it, the kind of tension we all feel when we have to attend to something we have been avoiding, like the dying of a difficult brother who has constantly sneered at your life, your house, your kids, your spouse, et cetera, ad nauseum, or the ending of a romantic relationship with someone who does not have your back and never will because they are much more concerned with the false front they present to everyone else.

There is sadness, yes, because this is a book about vulnerable children and teens and mature, usually, adults who struggle with hard knocks and gain depth and wisdom. These are characters so real they practically stride off the pages or sidle up and try to bum a smoke off you. Harsh and hopeful lives lit up by glimmering flashes of joy and towed along by undercurrents of humour.

In ‘Can’t Go Wrong With an Iris,’ we meet a sixteen-year-old mother, attempting to look after her newborn, who must contend with her own ineffectual, self-absorbed mother dedicated to avoiding responsibility, never mind possessing the grandmotherly gene. The basement suite-dwelling teen must accept the fact her own mother will bail on her yet again. Then she must face the formidable mother of the fifteen-year-old father of her baby, who at least brings two bags of groceries, a cheque and a bouquet of irises before fleeing.

Our teen mother declares, as she heads for the door, that her son has a future, high-stepping through the muck left behind by a recent flood. I cheered on the abandoned young mom, tough, and with a bright and beautiful heart, much like an iris.

The title story, like all the sixteen powerful stories in The Promise of Water, is grounded in place and seemingly tethered there by indelible memories. It’s about one boy’s dream of swimming in the Olympics and his mother’s promise to buy him swimming lessons in a pool year-round, not just Shawnigan Lake across the road in the summer. A reluctant teenage cousin from Nanaimo is pressured by his own mother to spend a week with his younger cousins, so she and his father can spend a week in Vegas. The cousins, including the would-be Olympian, are the kind of brothers who sneer and slap and punch each other non-stop, competing for the attention of their boozehound father, who eggs them on when he returns from his well-worn chair in the local Legion. His aunt copes by playing the perpetual comedian with rose-coloured glasses resolutely attached to her head, and by working three night shifts a week at a retirement home to keep the family fridge stocked with weiners (and flats of Lucky Lager, I surmise, to pacify her seasonally-employed husband).

Hope floats like so much dandelion fluff and tragedy ensues. The writing is so evocative, so pitch-perfect I keep returning to these characters with ‘what if’ scenarios, wanting to bargain on their behalf for better choices and happier outcomes for them all.

LeBlanc deftly shows us what economic and social and educational class differences really look and sound and taste like. Her adult characters work at all kinds of occupations from group home parents to English as a Second Language teachers to loggers and miners and kayak guides. Parenting by men and by women gets its fair share of scrutiny and some of us, as the report cards indicate, have room for improvement and that’s an understatement. But we cannot help but feel empathy for those souls who are truly doing the best they can, too.

Take Darren, in ‘The Confusion Technique,’ who prefers to be called Thesp, for thespian. As an erstwhile co-house parent in a challenging group home, he writes a farewell note to Amy, his girlfriend of several years duration, who is in way over her young, earnest head with the streetwise teens: ‘I’ve been talking to my father again. He’ll set me up if I finish my degree: tuition and an apartment. He says I’ve got to live up to my potential. I know you don’t believe it, but I could be anything I want. It’s been a gas. We had some nice times, you and I, and likely we’ll miss each other now and then. Take care and all the best.’

Thesp has avoided successive house parent meetings with the social worker by wrapping himself in a carpet and getting into method acting while employed by Lug-A-Rug and waving at traffic on Blanshard Street in Victoria. Amy has been dealing with keeping hard-partying young women alive in the age of deadly drugs and morose, towering youths with knives strapped to their boots. She emails the feckless Thesp, after summing up her life to date and their relationship on her own terms, with these overdue words: ‘This is not a gas, you clown.’

‘Exposure’ is a stunningly good story set in the mining town of Cumberland in the first half of the last century. A miner’s widow looks after her father who is dying of Black Lung or silicosis. The prevailing working man’s suspicion of anyone without coal-seamed hands is compounded by racism when a photographer, known locally as ‘The Jap,’ dares to walk the same streets nattily dressed in a suit with a fedora on his head. ‘The Jap’ is very good at what he does. Everyone in the segregated town who can afford to hire him does so to photograph their weddings and family portraits. But he sets tongues wagging when he advertises for a white lady to model for him, for which he will pay cash. The miner’s widow is the only woman who applies and she has a particular grievance to sort out with the photographer, who also has the nerve to call himself an artist.

This is a terrific debut and a book to reread just to admire the use of the language and to spend more time with some classic Vancouver Island characters. I found myself revisiting these characters as they set their sights on freedom and a better way of living and expressing their best qualities in this world.

Judy LeBlanc is a North Island College English and Creative Writing instructor and founding member and artistic director of the popular Fat Oyster Reading Series, yet another good reason to go to the Fanny Bay Community Hall with a pit stop at the Fanny Bay Inn, aka The F.B.I., afterwards.

Caroline Woodward is a lightkeeper on Lenard Island, near Tofino.

Leave a Reply