Bringing back Chinatown Ghosts

The first slim book by Jim Wong-Chu in 1986 was just the beginning of his formative work leading the way for Asian Canadian literature in British Columbia.

April 15th, 2019

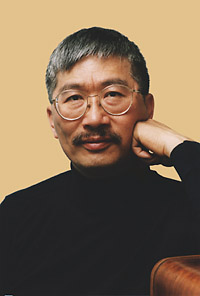

Jim Wong-Chu (1949-2017). Photo by Glenn Deer

“What a force of literature, creativity, and change Jim Wong-Chu helped to unlock,” says reviewer LiLynn Wan.

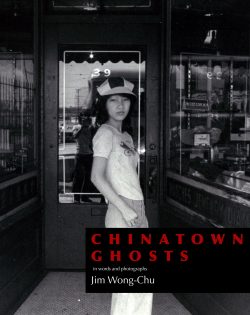

Chinatown Ghosts: The Poems and Photographs of Jim Wong-Chu

by Jim Wong-Chu

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018

$19.95 / 9781551527482

Reviewed by LiLynn Wan

*

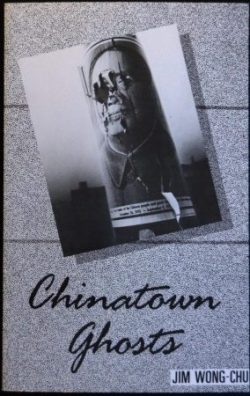

When Chinatown Ghosts was first published in 1986, Jim Wong-Chu broke a silence in Canadian literature. This slim volume of poetry was one of the first English language literary publications by a Chinese Canadian writer about the Chinese Canadian experience. The book was initially denigrated by many in Vancouver’s Chinatown community because of the defaced image of Mao Zedong that graced its cover, and it received little notice outside of that community. It was, as Wong-Chu describes in the opening poem of this collection, a way of “unlocking” to “begin to open.” And what a force of literature, creativity, and change Jim Wong-Chu helped to unlock.

When Chinatown Ghosts was first published in 1986, Jim Wong-Chu broke a silence in Canadian literature. This slim volume of poetry was one of the first English language literary publications by a Chinese Canadian writer about the Chinese Canadian experience. The book was initially denigrated by many in Vancouver’s Chinatown community because of the defaced image of Mao Zedong that graced its cover, and it received little notice outside of that community. It was, as Wong-Chu describes in the opening poem of this collection, a way of “unlocking” to “begin to open.” And what a force of literature, creativity, and change Jim Wong-Chu helped to unlock.

The posthumous republication of Chinatown Ghosts in 2018, scarcely more than three decades later, takes its place as tribute and legacy amidst a flourishing canon of Asian Canadian and Pacific Rim literature that has claimed national and international recognition. Although Wong-Chu published little of his own writing after Chinatown Ghosts, he worked consistently until his passing in 2017 to support and mentor countless emerging Asian Canadian writers and artists. He sought out Asian Canadian writers (in the days before the internet) and published anthologies of Asian Canadian short stories and poetry. He co-founded the Asian Canadian Writers Workshop, Ricepaper Magazine, and the LiterAsian Festival, all of which are thriving today. Wong-Chu’s photographs and poems in Chinatown Ghosts map his early steps in articulating a collective Asian Canadian identity, history, consciousness, and voice that lay at the heart of his lifelong activism.

The impact that Jim Wong-Chu left on the Asian Canadian literary community is made clear in the many tributes and homages which preface this 2018 republication of Chinatown Ghosts. This new edition also includes a selection of his photographs of Vancouver’s Chinatown taken in the 1970s and early 1980s that are thoughtfully arranged in composition with his poetry.

Many of the poems in this collection identify place, culture, and history as central to Chinese Canadian identities. Poems like “tradition,” “the old country,” and “peasants” describe a consciousness and experience that extends beyond the confines of Vancouver’s Chinatown and the borders of British Columbia, across the Pacific Ocean to China. For Wong-Chu, many places are home, and culture exists in those small acts of tradition, and of food, work, and family relations, that remain constant across geographic borders. This diasporic understanding of place and culture is central to the author’s conception of an Asian Canadian identity.

In these poems, temporal borders are also fluid, as history weaves through the author’s present. In “journey to merritt,” we are accompanied by the ghosts of nineteenth-century railway workers. In an “old Chinese cemetery” in Kamloops, we “walk/ on earth/ above the bones/ of a multitude of golden mountain men.” The ghosts of railway and cannery workers, gold miners, and peasant farmers who suffered exploitation, discrimination, and poverty haunt this literary journey of self discovery. Nonetheless, there is at the same time an overarching sense of humour and hope.

This duality is most apparent in layout of the poem, “equal opportunity.” Here, a photograph of the “Iron Chink”[1] in the Royal BC Museum is placed next to the first half of the poem, which describes how the Chinese were once forced to sit in the back, and then the front of the train. In each case, an accident claims the lives of the passengers in the front, and then the back of the train. In each case, “the Chinese erected an altar and thanked buddha.”

On the next page is a photograph of three men in suits and hats, sitting relaxed on a stair railing on a sidewalk somewhere in Chinatown, the man in the centre looking straight at the camera, arms crossed, a quiet and deliberate smirk on his face. Next to this, the poem concludes, “after much debate/ common sense prevailed/ the chinese are now allowed/ to sit anywhere on any train.”

The history of the Chinese in Canada in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is recalled in these poems as a history of discrimination driven by economic necessity. Labour is a central theme in this collection, as it is to the history of the Chinese in Canada, to Vancouver’s Chinatown, and in the author’s own life. Wong-Chu ended his formal education after the tenth grade and worked in restaurants before taking on a career as a carrier for Canada Post. The hilariously wry “Jimmy the waiter” as well as painfully stoic pieces like “eggroll kid” and “the newspaper vending kwan yin,” bring us into the working world of the second half of the twentieth century.

The alternate placement of poems that describe the emotional toll and harsh reality of modern working life in Chinatown, alongside poems that recall historical periods of intense discrimination and racism against the Chinese in British Columbia, highlight connections between past and present that were central to Wong-Chu’s conception of identity.

Poems like “fourth uncle” and “of course there are ghosts” use family to discover what was carried through the generations as well as what was left behind. In “mother,” Wong-Chu explores women’s labour, marriage, and family dynamics. He describes with painful accuracy the loneliness and tedium of being wife and mother in a low-income Chinatown household. The poem begins, “she always wears her silence / in front of father.”

In a similar vein, the poem “how feel I do” explores the shame of being a new immigrant who is not yet able to speak English alongside the corresponding shame of losing one’s own language. Wong-Chu was brought to Canada as a paper son,[2] which means that his own family history was shrouded in silence. The theme of silence lies at the heart of this collection, not as subject but as target. When Jim Wong-Chu published this collection in the 1980s, Asian Canadians were generally silent in mainstream media as a result of institutionalized racism over the community’s 150-year history. His poems and photographs emerged out of a compulsion to say something fundamental, which, in the 1980s, had not yet been said loud enough to be heard: We Are Here.

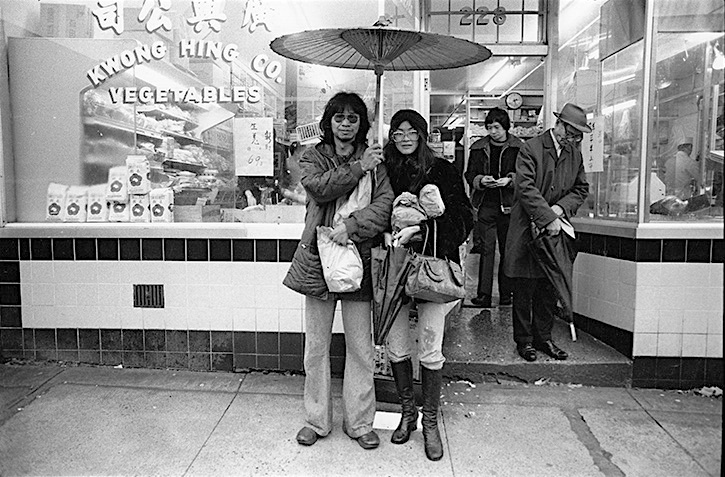

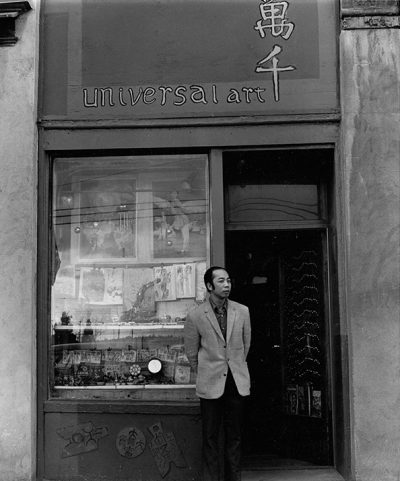

Jim Wong-Chu’s photographs are exceptional, both aesthetically and historically. Most of those included in this volume are portraits of people, working class residents of Chinatown at work and play. They capture a time and place that has disappeared, but whose story of a struggle to find identity and belonging is still relevant in a country where immigration continues to play a significant and controversial role.

Unknown couple at Kwong Hing Co. meat market and vegetables, East Pender Street, circa 1978. Photo by Jim Wong-Chu

When Chinatown Ghosts first appeared, in 1986, I was ten years old. I thought then that Chinatown was a constant, a place that always was and always would be. I realize now that it was home, but the goal was never to stay. For many of us who grew up in that era, assimilation was success, and that meant moving away from Chinatown. Today, Vancouver’s Chinatown continues to face gentrification on one hand, and on the other deterioration where it borders Vancouver’s drug-ridden Downtown Eastside. The Asian population in Vancouver has changed dramatically in the last thirty years, to where Asian Canadians have taken leading roles in economics, politics, and culture. There is a nostalgia to these photographs, but in hindsight they are also a celebration of the many successes of the Asian Canadian community and of the actualization of Jim Wong-Chu’s vision of a vibrant Asian Canadian identity and culture.

Jim Wong-Chu wrote what he knew. His poems and photographs have a humility and authenticity that is enticing, captivating, and endearing. His poetry, like all good poetry, speaks to universal human experiences, but his comes from a distinctly Asian Canadian perspective. The 1980s to 1990s marked the early stage of a period of heightened political consciousness and awareness of a collective social identity for Asian Canadians that was to come to maturity by the first decade of the millennium.[3] Academics focused on the valuable tasks of writing about the politics, legality, geography, social organization, discrimination, racism, and inequality associated with Chinatown.

But grassroots activists like Wong-Chu understood early on that this was not enough. He recognized the importance of encouraging the contemporary production of art and culture, including literature, from within the Asian Canadian community and for the Asian Canadian community.

Chinatown Ghosts captures the essence of the human spirit in a particular time and place. Jim Wong-Chu’s extraordinary legacy is retained in his words and images, a testament to his life’s work in guiding a generation of Asian-Canadians silenced by racism to voice their humanity.

*

LiLynn Wan is a full-time potter currently living in Herring Cove, Nova Scotia. She produces functional dinnerware, kitchenware, and teaware. Her work is inspired by classical Chinese, Korean, and Japanese ceramics, aesthetics, and philosophies of craft. She holds a PhD in Canadian history from Dalhousie University.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Footnotes:

[1] “Iron Chink” was the nickname for the automated industrial machine for butchering and cleaning fish that was invented in 1906. The name denotes the racism that was rampant in British Columbia at the time. In the case of the Royal BC Museum artifact, the name “Iron Chink” is cast in iron on the front of the machine.

[2] “Paper Sons” is a term used to describe individuals who were brought to Canada and the United States from China, often as children, using false documentation. These documents (papers) could be bought, and were often those of a deceased child or individual.

[3] For more on the history of Asian Canadian Activism, see Xiaoping Li, Voices Rising: Asian Canadian Activism (UBC Press, 2011). For more on Wong-Chu’s role in this movement, see Zhen Liu, “”The Generation that Responded to Duty”: An Interview with Jim Wong-Chu” in Ricepaper Magazine (15 June 2017), <https://ricepapermagazine.ca>, accessed (25 March 2019.)

Jim Wong-Chu at exhibition of his photographs at Centre A (Vancouver International Centre of Asian Art), Keefer Street, 2014

Leave a Reply