#249 Binning House (1941 – ?)

February 19th, 2018

Binning House

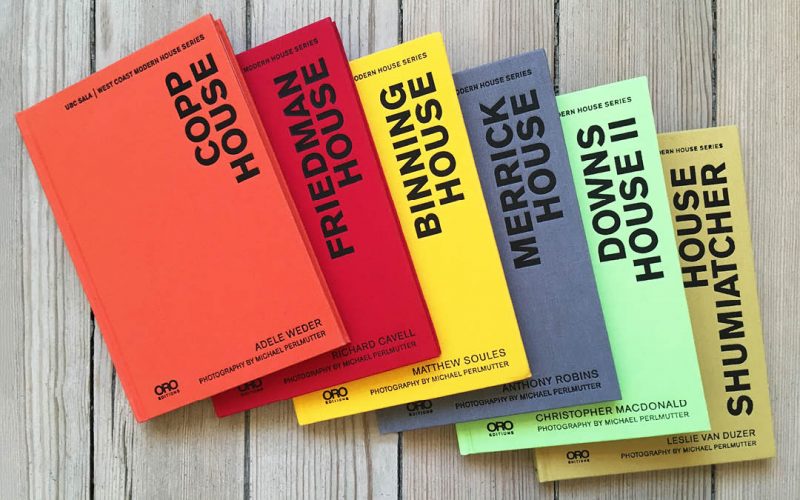

by Matthew Soules (text) and Michael Perlmutter (photography)

Novato, California: ORO Editions, 2017.

$24.95 (U.S.) / 9871939621665

Reviewed by Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe

UBC SALA/West Coast Modern House Series

*

Architecture critic Adele Weder is now trying to preserve the much-admired house that was built and designed by Bert Binning in West Vancouver for his home in 1941. Now deemed a modern classic as the first example of West Coast Modernism, it is currently privately owned. “It’s like the DNA for West Coast Modernism and West Coast cultures,” says Weder, founder of the West Coast Modern League and interim editor of Canadian Architecture magazine.

The Binning house was privately purchased in 2015 by a realtor after an insolvent charity failed to preserve it. There are now plans to sub-divide the lot on Mathers Crescent. Weder claims the heritage value of the house would be lost if a new home was to be built in front of it.

Bert Binning died in 1976. His wife Jessie continued living in the house until she was in her nineties. She died in 2007 at age 101. In her will, Jessie Binning stated she wished the home to be preserved and made available to the public for scholarly research. She succeeded in having the home accorded heritage designation before she died, seemingly making it illegal for the property to be subdivided. The municipality of West Vancouver is now discussing the realtor’s application for subdivision. – Ed.

*

Contemporary reviews sometimes seem, like the constant “breaking news,” to be more about sensation than sense and often seem to run parallel instead of attending to the text in hand. Perhaps this is an aspect of the digital media’s tendency to encourage hyperbole and crunched articulation in place of cogent consideration.

Why this preamble? Because the contents of this handsomely produced and illustrated book tends towards critical myopia and inflated language. And because this reviewer should acknowledge a potential subjectivity proceeding from a long acquaintance with the subject. I initiated the placing the Binning House on the National Register of Historic Buildings, lodged Binning material in the archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, and wrote The New Spirit: Modern Architecture in Vancouver 1938-1963 (1996) – which, oddly, is omitted from this book’s notes.

As noted, Binning House has many commendable attributes and the short text certainly conjures up much of the enduring appeal of this house and, more broadly, the regional legacy of the modern movement in architecture, planning, and design.

The format of the book, its physical form, is both appealing and attuned to the strategy of UBC SALA (School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture) /West Coast Modern House Series of studies of single houses to which it belongs.

Bert and Jessie Binning at Binning House, 1951. Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal.

The buff woven binding nicely sets off the excellent typography of the cover. The vertical printing of the title Binning House recalls the radical rethinking of media design and lettering that accompanied the early development of the modernist ethos, perhaps culminating in the multidisciplinary curriculum and production of the post-1923 Bauhaus.

Incidentally, the implementation of what was, literally, a cleaner aesthetic in print-based communication had occurred in the Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada under the editorship of Eric Arthur.

On faculty at the School of Architecture at the University of Toronto, Arthur taught several of Binning’s colleagues, notably Charles [Ned] Pratt, who had a significant part in the design of the Binning House, and Fred Lasserre, who hired Bert Binning to teach in the School of Architecture and now the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture). That alliance of practising art and architectural practice was core to the middle period (1930s through to the 1960s) of Canadian modernism.

The refined amalgam of visual, tactile, and cognitive composition continues inside the covers of Binning House. The endpapers recall Binning’s fascination with lyrical geometries and pattern – particularly evident in the mosaic murals he devised for the former B.C. Electric Building, again working chiefly with Pratt.

The paper and font match the mis en page of original renderings and art works by Binning, historic and contemporary photographs (the latter taken by Michael Perlmutter), and a commendable sequence of line drawings showing the site, floor plans, and elevations, which transpose Binning’s more exploratory linear abstraction of natural scene and scenery into elegant precision.

Following brief foreword and acknowledgements, Soules’s commentary is divided into three sections: Introduction; Insides and Outsides; and Monument, Geometry, and Optics. Each contains interesting insights about the potential intellectual and sensory stimulation attainable through the composition of structure and related manipulation of space – both perceived within and beyond its immediate dimensions – and through the choice of materials.

There can be no doubt of the particular delight of the setting of the Binning House. Once open to the vista across English Bay from the steeper, lower slope of West Vancouver, foliage gradually obtruded upon views of the shore and sea so beloved to Bert Binning and his wife Jesse.

Since its construction in 1941, Binning House has been increasingly beleaguered by the furious pace of real estate in the Vancouver region and by the melancholy absence of binding heritage legislation, governmental funding, or tax-relief provision.

This rather dire situation has partly prompted SALA’s studies of individual buildings. It perhaps also explains the sometimes heavily laden language of the commentary on what might be termed the contemporary experience of being at and in the Binning House.

Soules takes us on a tour of the house exterior and interior and reveals many intriguing features, such as the angling of the river rock living room wall and the effective integration of inside and outside space through folding, fully-glazed, wooden doors.

Soules also introduces wider historical analysis. One example is his recognition of natural landscape for modernist design formulation in which irregular topography or plant growth complemented the geometrical and functional principles underlying modernist architecture.

Other colleagues of Binning — such as architect-planner Peter Oberlander and landscape architect Cornelia Oberlander, both with direct links to European and United Modernism — exemplified the realization of essential differences between artificial and natural form, and in company with Binning eschewed the picturesque or associative domains.

While welcoming the updated genre of art-architecture appreciation, Soules’ articulation of design effect and affect can be cloying, especially in light of the original purpose pursued by Binning and Pratt. Take the sentence printed on the back cover:

Conjuring intellectually expansive sensorial experiences, the Binning House generates its own unique spatial world – a gentle super-reality – in which architecture traverses elemental conditions of building and life, and does so with ingenious modesty.

This house and another nearby, built for the Keay family in 1947, were designed as models for low-cost accessible housing as part of modernism’s powerful social project to redress the deep deficiencies in society disclosed by the First World War. The Binnings, with limited resources, intended this house to serve several functions, including display of Bert Binning’s art work.

This house and another nearby, built for the Keay family in 1947, were designed as models for low-cost accessible housing as part of modernism’s powerful social project to redress the deep deficiencies in society disclosed by the First World War. The Binnings, with limited resources, intended this house to serve several functions, including display of Bert Binning’s art work.

Thus it was not regarded as special but as part of the broad redirection of culture toward social reform. John Russell, for example, head of the School of Architecture at the University of Manitoba, enjoined the profession in a series of articles in the late 1940s and early 1950s to exchange traditional association with power for service to the wider community.

The Binning House, and indeed the other houses in SALA’s series, needs to be comprehended in context much as the West Coast iteration of modernism actually gains value when measured against the rich patrimony of modernist design across Canada.

*

Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe headed the department (Fine Arts, now Art History Visual Art and Theory) established by Binning at UBC, and the Individual Interdisciplinary Programme before serving as Associate Dean of Graduate Studies at UBC. A Guggenheim Fellow and recipient of the Margot Fulton Award, his many publications on architectural history include Francis Rattenbury and British Columbia: Architecture and Challenge in the Imperial Age (UBC Press, 1983, with Anthony Barrett); The New Spirit: Modern Architecture in Vancouver, 1938-1963 (Douglas & McIntyre, 1996); Architecture and the Canadian Fabric (editor) (UBC Press, 2011); and Canada: Modern Architectures in History (Reaction Books, 2016, with Michelangelo Sabatino). As Rhodri Jones he wrote on the re-membering of memory in Edges of Empire: A Documentary (Rarebit Press, 2017).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply