#196 Batten down the anthology

November 06th, 2017

REVIEW: Spindrift: A Canadian Book of the Sea

by Michael L. Hadley and Anita Hadley (editors)

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2017.

$36.95

978-1-77162-173-1

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

In this review of Spindrift: A Canadian Book of the Sea, edited by Michael and Anita Hadley of Victoria, Theo Dombrowski finds that, despite its unavoidable reliance on white male perspectives, the anthology provides an effective combination of sail and ballast. – Ed.

*

This is an anthology with something like a mission. In “Waypoints,” his foreword to this anthology, historian and editor Michael L. Hadley says that this Canadian Book of the Sea “presents a new kind of Canadian mosaic. The metaphor of the mosaic is, of course, usually applied to Canada’s cultural diversity to suggest that out of varied fragments there emerges a coherent whole, what Hadley describes as a “striking unity.”

Arguably, and putting aside the question of unity for a moment, it is the variety in sources of the “mosaic” that is one of the book’s chief attractions. It is the kind of book that has something for everyone. Or almost everyone.

In fact, as joint editor Anita Hadley points out in “Beginnings,” her own foreword, the original idea of making a book of exclusively literary pieces “soon moved beyond this rich source to include non-fictional writing: journals, histories, biographies, memoirs, even articles.”

The overwhelming task of researching so many and such diverse materials, let alone getting copyright permissions, makes this book in these terms alone an impressive achievement.

Anthologies vary widely in principle and purpose, of course. Robin Skelton’s Poetry of the Thirties (Penguin, 1964) is celebrated for the way it selects and groups materials to illuminate patterns in otherwise overwhelming variety.

Some anthologies, in contrast, make a virtue of their role as a kind of pot pourri or sampler. Interestingly, the cover blurb of Spindrift uses the term “treasury;” Hadley himself frequently calls this a “collection.”

Some anthologies, in contrast, make a virtue of their role as a kind of pot pourri or sampler. Interestingly, the cover blurb of Spindrift uses the term “treasury;” Hadley himself frequently calls this a “collection.”

How much the sense of a “Canadian mosaic” does emerge will obviously depend on individual readers. At least two questions might, for many readers, stand in the way of their feeling more unity than diversity — first, they might wonder what makes a perspective Canadian, and second they might wonder about the vast separation between writing about the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific.

As for the first question, it is tempting to turn to Margaret Atwood. In her seminal book Survival (Anansi, 1972), Margaret Atwood raised a lot of eyebrows for her claims about the essential mentality of Canadians eyeball to eyeball with nature. For one thing, it seems we are not the same as Europeans or Americans. Europeans rhapsodize about nature or mythologize it. Americans give it mystic properties — or conquer it. Not so Canadians. For us, apparently, nature is a purely physical force and not a very pretty one. We experience it physically. And, maybe, we survive it. If we’re lucky.

So does this book reinforce Atwood’s claim? Does the Canadianness of the book emerge from what we have in common as, primarily, just survivors? Yes and no. What Michael Hadley calls “hazard and daunting challenge” is indeed a dominant theme. It is, however, not universal. Encounters with the sea take place in all kinds of moods and weathers, many of them benign or even, as Hadley says, “sublime.” Thus, whether the theme of survival or whether something else, unspecified, is enough to make the book “Canadian” is, many readers will feel, questionable.

Readers may also find questionable how much the Pacific and Atlantic kinds of writing merge. (The editors go out of their way to write about the third — Arctic — ocean and to include writings from and about the north, but, for obvious reasons, the book reads fundamentally as a set of book-ended perspectives.)

And it is hard not to feel that readers from B.C. will read the book very differently from those readers from “back east.” The sense of connection or recognition with Barry Gough’s piece on ships in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, for example, is very probably different for a British Columbian than for a reader from the Atlantic provinces. Likewise Harold Horwood’s description from White Eskimo of the spring ice break up in Labrador will be familiar to many from the east coast. To those from the west coast it will seem strange.

As for the vast majority of Canadians who never go anywhere near anything salty, we can only speculate. In her forward, Anita Hadley writes, “Whether we live close to the sea, or far from its shores, it is the oceans that bind our destiny and inform who and what we are as a nation.” Possibly.

As for the vast majority of Canadians who never go anywhere near anything salty, we can only speculate. In her forward, Anita Hadley writes, “Whether we live close to the sea, or far from its shores, it is the oceans that bind our destiny and inform who and what we are as a nation.” Possibly.

But possibly not. Louis Dudek’s poem, “Coming Suddenly to the Sea,” perhaps the best poem in the book, gives a tightly-worked insight into the experience of someone who breaks out of the landlocked constraints of the vast majority of Canadians. He ends his “long blind years” at the age of twenty-eight by standing on the shores of an Atlantic beach and returning with “a fistful of blood-red weed.” His is the only insight in the book into the perspective of a landlubber, but at least for him it was necessary to stand on the shores of the sea to have his eyes opened.

So, back to the question of unity. The very title – Spindrift — evokes, as the Hadleys remind us, flung bits of spray. And flung these bits are — though carefully selected. We are told that passages were chosen from a long list of potential entries if they were “brief, representative and engaging.” In the end, readers will probably enjoy the book most if they respond to the passages because they are brief, representative, and engaging — “flung bits of spray.”

Doing so is made all the easier by two of the Hadleys’ editorial decisions. One is to group passages under headings. Instead of arranging the entries by chronology, by location, by genre, or by occupation, for example, the editors have chosen to put their selections into clusters of similar subject matter. This method of organization has the great advantage of allowing browsers to zero in on chapters like “Vessels,” “A Noise of War,” “Migration and Exile” (three of the most focused of the ten chapters).

Likewise, the Hadleys provide each segment with a title (though denotative titles like “The Halifax Explosion” or “Log Salvage — West Coast Style” are more useful for browsers than connotative titles like “A Sovereign State of Mind” or “Sparks”.) In addition, the short editorial introductions to each passage are tailored for readers who are dipping and diving: basic information — about, for example, the history of the St. Roch — is repeated from segment to segment.

Other organizational approaches make selective reading less easy. First, the names of the sources appear at the end of each segment — a structure that, for some thorough readers, will mean a lot of flipping back and forth. Second, introductions to each passage can only do so much. Though immensely knowledgeable and helpful, the introductions focus primarily on background circumstances and history. Those who are curious about the author or the work from which a passage is drawn, and even whether, for example, it is a novel or an autobiography, will be busy googling.

Still, the introductions are often fascinating. The ones on war brides, for example, and on the Newfoundland sealing disaster of 1914, are virtually as interesting as the selections that follow from Janet McGill Zarn’s “My War-Bride’s Trip to Canada” and Michael Crummey’s poem from Hard Light. Other equally fascinating examples are the introductions to the excerpts from Donald MacGillivray’s “Cape Bretoners in the Victoria Sealing Fleet, and Beyond” and from Peter C. Newman’s “Company of Adventurers.”

Not all these introductory passages are parallel in approach or substance. Poems in particular are often left to speak for themselves. At the other extreme are the often affecting introductions, which make heartfelt comments on abuses or injustices, especially in the chapters on immigration and collapsing fisheries.

Comparatively few, but often stimulating, are those introductions that give an analytical or interpretative slant. George Whalley’s poem “Finale” is, the editors write, “marked by its realism and mythic dimension.” Of Joshua Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World they say, “His memoir … is a classic: vivid, fast-paced and reflective, always delightfully understated, and frequently opinionated.”

A perhaps unintended advantage of grouping passages under separate headings is that they can, as clusters, appeal not just to different interests but also to different tastes. Readers who like emotive writing about the sea and share a gusto for the “sublime” will be well pleased to find lots of elevated writing in the first two chapters, “The Face of the Deep” and “At the Edge.”

In the passage from Tom Koppel’s Ebb and Flow: Tides and Life on Our Once and Future Planet, for example, we read, “Seagulls wheeled and swooped over the tumult and foam, hunting for fish that had been injured in the natural cataclysm or simply thrust to the surface by the powerful upwellings.”

In the passage from Tom Koppel’s Ebb and Flow: Tides and Life on Our Once and Future Planet, for example, we read, “Seagulls wheeled and swooped over the tumult and foam, hunting for fish that had been injured in the natural cataclysm or simply thrust to the surface by the powerful upwellings.”

Similarly, from Greg Chochkanoff and Bob Chaulk’s SS Atlantic: The White Star Line’s First Disaster at Sea comes the following: “During these wild events, waves well over fifty feet high explode against the unyielding granite, sending millions of tons of water surging over the rocks and carrying away anything movable, even huge boulders….”

On the other hand, the chapters on “Vessels” and “A Noise of War,” both with a strong (stereotypically) “male” tone, are largely fact-based. To be fact-based is not, however, to be matter of fact: the passages on boats, mostly nostalgic, are often coloured with language praising this boat because it is “valiant” or that boat because “she lifts her bows with the sauciness of a young girl.”

Joseph Schull in The Far Distant Ships tells us that “The men of the merchant ships wrote an epic which will not be forgotten while the nation remembers its past….” Likewise, the passages on war, though freighted with lots of information on equipment, boats, munitions, and tactics, are also charged with lots of hair-raising disasters and brutal misery. Though only in fragments, the rhetoric of courage and glory does crop up, as, for example, in Archibald MacMechan’s selection from Songs of the Maritimes: “… they fought their guns and kept the Old Flag flying to the last/ but they died to shield the Right….”

At almost the other extreme, though, is the antidotal excerpt from Earle Birney’s (semi) comic novel describing the anti-hero’s uneventfully anti-heroic crossing of the Atlantic: “there was far too much and all the same.”

In fact, the whole collection has, arguably, a predominantly “male” ethos and a general drift towards well-worn tropes surrounding matters nautical. As Michael Hadley writes in his part of the introduction, “The written record projects ‘the sea’ as a predominantly male domain: visceral, aggressive, challenging and subject to mastery by commanding figures.” Likewise, if there are character traits that occur most often, they are courage and grit.

In fact, the whole collection has, arguably, a predominantly “male” ethos and a general drift towards well-worn tropes surrounding matters nautical. As Michael Hadley writes in his part of the introduction, “The written record projects ‘the sea’ as a predominantly male domain: visceral, aggressive, challenging and subject to mastery by commanding figures.” Likewise, if there are character traits that occur most often, they are courage and grit.

Additionally, of course, the whole world of storms, ships, conflicts, and disasters will appeal more to certain sensibilities than others. The chapter of “Portraits” tends, unsurprisingly, to be dominated by Old Salts (though there are refreshing exceptions). Pierre Berton’s piece from My Country: The Remarkable Past about “Old Slocum” is but the most colourful — and salty — of many others like it.

The predominant culture is not just male but white European male. The editors can select only from what materials exist, and, to their credit, they have attempted to include at least a few pieces that touch on some Indigenous perspectives. The selection about Whalers from Northern Voices by Aksaajuuq Etooangat is a memorable example.

Likewise, and in spite of limited sources, the editors include several passages by women, selections which are consistently remarkable for startling perspectives or little known insights. Still, those picking up the book should know that what they will find, though well worth exploring, is largely the white male experience.

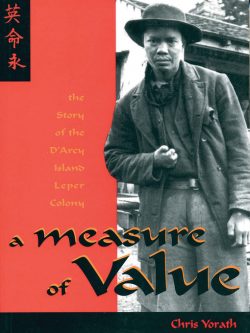

Arguably, the book achieves its greatest impact for the refreshing insights and powerful writing of some individual passages, for example the extract from Chris Yorath’s A Measure of Value about the leper colony near Victoria, and the extract from Audrey Thomas’s richly-detailed and emotionally complex account of a fishing haul in “Kill Day on the Government Wharf.”

Arguably, the book achieves its greatest impact for the refreshing insights and powerful writing of some individual passages, for example the extract from Chris Yorath’s A Measure of Value about the leper colony near Victoria, and the extract from Audrey Thomas’s richly-detailed and emotionally complex account of a fishing haul in “Kill Day on the Government Wharf.”

A Newfoundland fisherman’s reaction to the impact of industrialized trawlers from Donna Morrissey’s Sylvanus Now, and a thoughtful first person account of a little-known operation during the Second World War by Gordon W. Stead in A Leaf upon the Sea are likewise memorable. Wayne Johnston’s piece from Baltimore’s Mansion creates a sense of vivid authenticity in its depiction of the swarming run of tiny “capelin.”

Emily Carr is always worth reading for her unpretentious and clear-eyed handling of detail. Her passage from Klee Wyck is an exquisite example. Though nothing more than an account of an uneventful boat trip with two Indigenous people in what is now called Haida Gwaii, it epitomizes the thoughtful honesty of good writing.

Emily Carr is always worth reading for her unpretentious and clear-eyed handling of detail. Her passage from Klee Wyck is an exquisite example. Though nothing more than an account of an uneventful boat trip with two Indigenous people in what is now called Haida Gwaii, it epitomizes the thoughtful honesty of good writing.

For such passages, and others like them, this book is well worth reading, sequentially or randomly. Browse through the passages, read and reread those that stand out, and, perhaps, use them as starting points for further reading.

At its most useful the book will act as an incentive to read more — whether a novel like Donna Morrissey’s Sylvanus Now, or a history like Chris Yorath’s A Measure of Value: The Story of the D’Arcy Island Leper Colony.

Above all other pleasures, Spindrift will stimulate interest in a range of rich and sometimes forgotten examples of good writing created by Canadians responding to experiences with the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic Oceans.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and UVic. He is the author and illustrator of popular guide, travel, and hiking books including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island: Streams, Lakes, and Hills from Victoria to Nanaimo (Rocky Mountain Books, forthcoming 2018). Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply