B.C.’s mighty sea otter

After being wiped off B.C.'s west coast between 1929 - 1930, otters from Alaska were successfully re-introduced in the 1960s, as told in Isabelle Groc's new book.

February 03rd, 2020

Sea otters are often seen in kelp forests, which protect them from strong ocean waves.

Being a “keystone species” otters have the power to hold an ecosystem together and their return to B.C. started a chain reaction that boosted kelp forests and other species.

Review by Beverly Cramp

While out walking by Vancouver’s seashore one day, Isabelle Groc spotted in the distance what she thought were masses of floating kelp bobbing up and down. But the movement was odd so she reached for her binoculars.

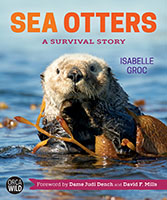

“What I saw was unexpected and magical,” she says. “About 120 sea otters holding on to each other, floating gently on the water and resting.” The incident inspired Groc to find out about these marine animals, the smallest in North America, and write Sea Otters: A Survival Story (Orca $24.95), a book for children aged 9 to 12.

“What I saw was unexpected and magical,” she says. “About 120 sea otters holding on to each other, floating gently on the water and resting.” The incident inspired Groc to find out about these marine animals, the smallest in North America, and write Sea Otters: A Survival Story (Orca $24.95), a book for children aged 9 to 12.

Sea otters have made a remarkable comeback after nearly being hunted to extinction for their fur coats in the 18th and 19th centuries. A few small communities of otters in remote places managed to survive and in the early 20th century laws were passed to protect the animals. Today, sea otters are widely studied but their existence is still threatened and classified as “endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened species.

In the 1960s, a number of sea otters were reintroduced to areas where they had been wiped out, including B.C. where the last original sea otters near the village of Kyuquot on Vancouver Island were killed between 1929 and 1931.

Sea otters from Alaska were brought to the west coast of Vancouver Island from 1969 to 1972 and an ecological reserve created to protect the colony in the Checleset Bay. They survived well and sea otters from Vancouver Island to B.C.’s central coast now number close to 7,000.

Kelp forests are vital for otters’ well-being. Many feed and rest around kelp forests, which provide them protection from strong waves. To sleep, sea otters often wrap themselves in pieces of kelp to keep from drifting away. And kelp forests are also safe places for females to nurse and raise their pups.

Otters like to eat while floating on their backs, using their bellies as a “picnic table.” Here, the meal is a geoduck.

Having a high metabolic rate, sea otters eat a lot – up to 25 percent of their weight every day. Their favourite food is sea urchins but they also feed on clams, abalone, crabs, mussels, sea cucumbers and even fish and seabirds. Once they catch their prey, sea otters float face-up and usually lay it on their stomachs, like a picnic table, and begin eating with their two front paws.

Importantly, sea otters are known as a “keystone species,” meaning they have the power to hold an ecosystem together. Otters keep sea urchin numbers down as urchins are their go-to chow. Alternatively, where there are no sea otters, there tends to be lots of sea urchins, creating a landscape that looks like a clear-cut with hardly any kelp or the animals that flourish upon kelp.

“The sea otters were the starting point of an unbelievable chain reaction that transformed the ecosystem around them,” says Groc. “This process is an example of a ‘trophic cascade,’ a domino effect whereby a predator at the top of the food chain can change an ecosystem through its impacts on prey.”

The reason we should care about kelp forests, says Groc is that they are among the most productive ecosystems in the world. They are active nurseries for many young fish. Larger marine mammals like sea lions and orcas use the kelp forests as hunting grounds. Plus, when kelp dies, it falls to the seafloor where other organisms such as abalone, snail and urchins eat them. All this richness is underpinned by the sea otter, the key to a rich, complex and connected ecosystem as illustrated by Isabelle Groc. 978-1-45981-737-1

*

Writer, wildlife photographer and filmmaker Isabelle Groc’s last book was Gone is Gone: Wildlife Under Threat (Orca 2019).

Leave a Reply