“At the time of my own choosing.”

As Parliament considers Bill C-14, Gary Bauslaugh’s poignant stories make us ask: How do I want to die?

July 21st, 2016

Review by Mark Forsythe

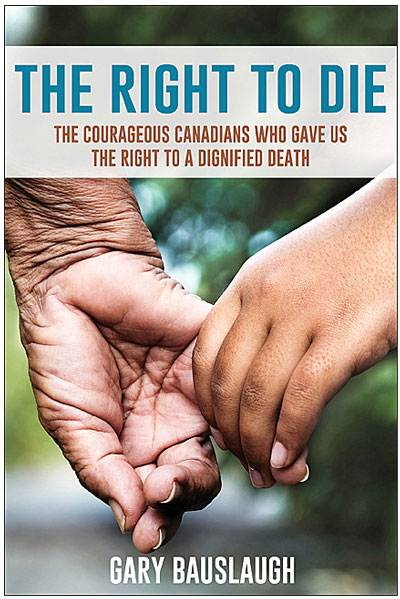

The heart-wrenching stories that Gary Bauslaugh tells in The Right to Die: The Courageous Canadians Who Gave Us The Right To A Dignified Death (Lorimer $29.95), begin with the Ramberg case in 1941.

That was when parents of a toddler living with a painful, incurable tumour “connected the exhaust pipe from their vehicle into the bedroom where the child’s crib was and turned on the ignition.” The boy died and his parents stood trial for murder, facing a possible death sentence.

The jury took ten minutes to find them both not guilty, nullifying the existing law and sending a powerful message about the limitations of the law around mercy killing.

This reluctance to find defendants guilty of murder has occurred in numerous instances.

The high profile case of farmer John Latimer, who killed his severely disabled daughter Tracy with carbon monoxide, is more complicated. Involuntary euthanasia is murder in the eyes of prosecutors and advocates for people with disabilities, who argue such killings devalue the lives of the disabled and are open to abuse. Latimer was convicted of second degree murder, served ten years in prison and became the subject of a book by Bauslaugh. (The author also helped Latimer get a job as an electrician.)

Bauslaugh thinks the Latimer case and ruling set back the cause for “compassionate assistance in ending of life.” Many Canadians were conflicted by this case, at a time when countries like the Netherlands and Belgium were opening up new options for assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Overall, Gary Bauslaugh examines 40 cases of assisted dying—many of which involve right-to-die advocates in B.C.

In 2015, the Supreme Court unanimously struck down the ban on medically assisted dying, ruling that the law was unconstitutional and breached the Charter. This was the provision Sue Rodriguez challenged. According to polls, the highest court got it right. A majority of Canadians now support death with dignity.

The new federal government was given an extra six months to craft a law that balances civil rights and the need to protect the most vulnerable. Bill C14 will now provide support to consenting adults with “grievous and irremediable” medical conditions that are incurable and intolerable.

Lee Carter, whose mother Kay Carter was central to the groundbreaking assisted dying litigation launched by the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, believes the new law will be too narrow and restrictive. Lee Carter’s mother travelled to Switzerland to legally end her life but she would not have qualified for medical assistance in Canada under the proposed new law.

Lee Carter, whose mother Kay Carter was central to the groundbreaking assisted dying litigation launched by the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, believes the new law will be too narrow and restrictive. Lee Carter’s mother travelled to Switzerland to legally end her life but she would not have qualified for medical assistance in Canada under the proposed new law.

The Canadian Medical Association believes the bill strikes the proper balance, restricting access for minors, people with mental disabilities and those whose deaths are not imminent.

Gary Bauslaugh, a former Humanist Association of Canada president, ably recalls the stark, painful circumstances people have faced in the fight for assisted dying—from Sue Rodriguez to Kay Carter and Gloria Taylor. The book inevitably includes lawyers Chris Considine and Joe Arvay, civil liberties advocate John Dixon and ethicist/philosopher Eike Henner Kluge.

Bauslaugh also details the efforts of B.C. activist John Hofsess and his Right to Die Society. Hofsess began thinking about a more dignified death when his filmmaker friend Claude Jutras jumped from the Jacques Cartier Bridge in Montreal after facing early onset Alzheimer’s.

“Hofsess felt guilty for not doing more to help his friend,” Bauslaugh writes, “backing away from helping him die partly because it was difficult to let go of his friend, and partly because he feared prosecution. Never again, he vowed, would he let that happen again.”

When Hofsess moved to Victoria and learned of an elderly couple who jumped from their balcony, he thought there must be a better way to end lives. Hofsess created an underground railroad to assist people with the decision to take their own lives by providing information, so called “Exit Bags” and, on occasion, direct assistance.

This continued until one of his colleagues, Evelyn Martens, began to operate on her own and went to trial. Bauslaugh documents the twists and turns of Martens’ trial, which he attended in 2004, at the end of which she was found not guilty.

It was the Gloria Taylor/Lee Carter B.C. Civil Liberties challenge that ultimately changed the law. Suffering from ALS, lead plaintiff Taylor wrote: “I do not want my life to end violently. I do not want my mode of death to be traumatic for family members. I want the legal right to die peacefully, at the time of my own choosing, in the embrace of family and friends.”

Taylor was granted an exemption to seek doctor-assisted suicide by the B.C. courts, but didn’t use the exemption as she died from a sudden, serious infection at the age of 64.

9781459411166

Mark Forsythe is a former CBC radio host and has written four books.

We need this conversation because the majority of Canadians want self-determination about the end of their lives. And I agree. I don’t think the state has any right to interfere in my personal and private decisions. They should abide by the SCC decision and back away from introducing it in the House.

As it is we all dread winding up in “The Home” where they, too, can and do interfere as with the poor soul they tease into eating. Hard to imagine the kind of pain this place has caused and how management, etc, can live with itself.