Another Peace offering

The 16 contributors to Damming the Peace: The Hidden Costs of the Site C Dam try to make sense of John Horgan’s decision to damn the river.

August 31st, 2018

In 2016, John Horgan donated to the Stakes in the Peace campaign to support resistance to Site C.

Peace River farmer Arlene Boon reminds us that “We have until the water rises to stop the dam.”

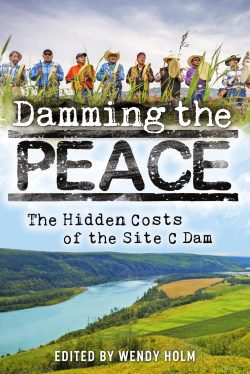

Damming the Peace: The Hidden Costs of the Site C Dam

by Wendy Holm (editor)

Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, 2018

$22.95 / 9781459413160

Reviewed by John Gellard

*

Damming the Peace is an anthology of articles that covers every possible argument against Site C. The authors — renowned scientists, economists, journalists, politicians, geographers, environmentalists — are unanimous in damning the project.

Damming the Peace is an anthology of articles that covers every possible argument against Site C. The authors — renowned scientists, economists, journalists, politicians, geographers, environmentalists — are unanimous in damning the project.

The Council of Canadians recently sponsored a book tour featuring author-editor Wendy Holm with stops in Victoria, Comox, Powell River, Nelson, Kelowna, and Kamloops.

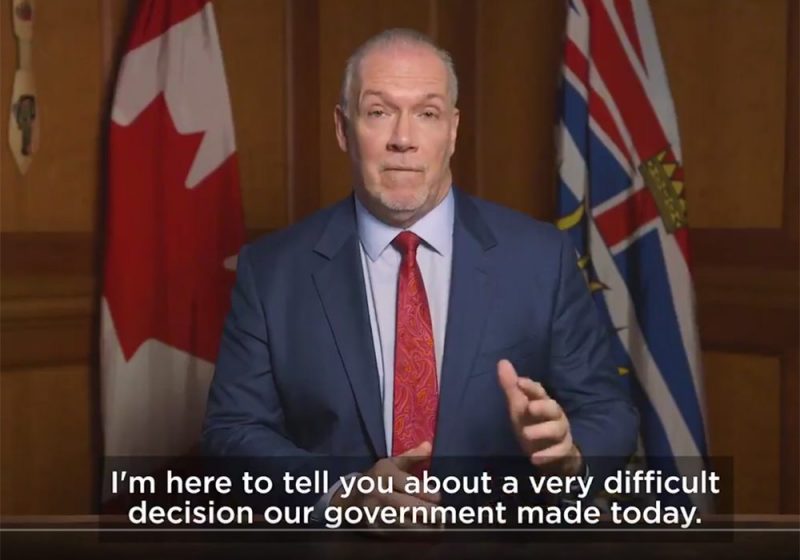

What on earth is it, then, this force that drives the project forward? Why hasn’t Site C been stopped cold? Why did the new NDP government announce on that fateful day, December 11, 2017, that it would proceed even though it was a bad idea? There is an “elephant in the room” — not the huge white elephant that you see at No-Site C rallies. This elephant is dark and invisible. The government does not talk about it.

It’s not the atavistic destructive mockery of nature that you might encounter on the canvassing circuit. You know: “We’ve got lots of land. They’re just flooding a little valley.” “Site C will create another Okanagan Lake! I’ll build a lakeside cabin.” “Oh, the fishing will be good and there’s lots of work in the clearing.” “We can always sell the power.”

No. This elephant is rather more sinister. Wendy Holm confronts it and exposes it. It’s about exporting water.

No. This elephant is rather more sinister. Wendy Holm confronts it and exposes it. It’s about exporting water.

I’ll review Damming the Peace by highlighting the sixteen essays and allow readers to plunge into the details on their own later. Each essay can be read separately.

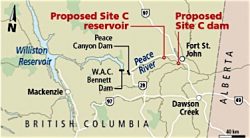

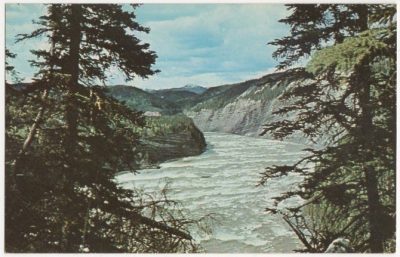

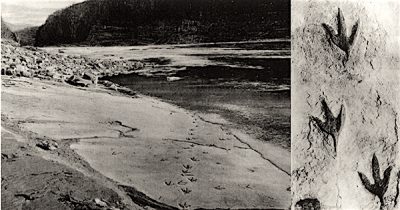

But first, where is the Peace River? For most of its course the Peace is – or was — a British Columbian River. The source is west of the Rockies, at 58 degrees north latitude where the Finlay River flows south, finds a gap in the Rockies, and turns east, to be joined by the Parsnip River from the south.

Now the Peace flows east through the canyon, emerges at Hudson’s Hope, and meanders through a wide alluvial valley 90 km to Fort St John, past Site C. Then it enters Alberta and turns north to the Athabasca Delta and the Mackenzie River, to flow into the Arctic Ocean.

That was then. In 1968, the W.A.C. Bennett Dam near Hudson’s Hope flooded a watershed the size of Ireland. That event is described in the book. Let’s move on and look at the authors and their essays.

Alex Harris, aged 24, already an accomplished videographer with Little River Productions, provides the preface and gives an apt metaphor for the structure of the book: “Framing the Shot. Focusing in. Widening the shot.” Harris provides links to several poignant videos of her interviews with people she sought out on her trips to the Valley.

Do we need the power? The short answer is “Yes,” says Guy Dauncey, eco-futurist. He gives us a thorough grounding in electric terminology. Did you know that B.C. might need 75,000 Gigawatt-hours per year by 2030, or that the 1,100 megawatt Site C Dam will generate 5,100 GWh per year?

But we don’t need this kind of power. Dauncey shows in detail how the demand can be met by renewables: solar, wind, geothermal, and intelligent Demand Side Management.

David Schindler, expert on dams and their impact on the environment, explodes the myth that hydro dams produce clean green energy. They can produce as much GHG as burning coal. They poison fish and obstruct fish migration. Other kinds of devastation are discussed elsewhere in the book.

Andrew MacLeod, award-winning journalist, considers Indigenous resistance. He presents the experience of Helen Knott, a young leader of the Prophet River First Nation. Her reserve is a whopping 3.8 sq. km. (that’s 940 acres for any geezers out there), while Dene Zaa territory is 25,000 sq. km.

Treaty 8 gives First Nations the right to pursue traditional vocations “except where the land may be taken up for settlement or other purposes,” which might include the flooding of the Peace River Valley and the resulting devastating harm.

In Chapter 4, Brian Churchill, professional biologist, identifies the Peace Valley an “ecosystem junction” and a “biodiversity hotspot.” The uniquely benign microclimate brings species from several eco-regions together with species not found outside the Valley. Churchill quotes from Alexander Mackenzie’s 1793 journal: “[T]his country is so crowded with animals as to [look like] a stall yard.” Here, Churchill says, “Governments have forsaken their traditional monitoring [of this] island of nature in a sea of human disturbance.”

Wendy Holm, in “The Rape of the Commons,” writes that “The rich alluvial soils of the Peace River Valley are part of our foodland commons. There to protect and enhance, not drown and destroy.” Loss of the commons has never been included in economic evaluations. It’s a so-called “externality.” Holm shows that 6,469 hectares will be submerged, and we will lose the capacity to feed at least a million people, per year, in perpetuity.

Former N.D.P environment minister Joan Sawicki exposes “The Big Lie” in the twisted logic behind Hydro’s failure to include the miraculously benign microclimate in its analyses. The suppression of this information is a “fatal flaw” in Hydro’s plans.

Andrew Nikiforuk, acclaimed science writer, contributes two essays in Damming the Peace. The first describes the dangers of fracking: the risk of earthquakes, the huge consumption of water, the discharge of toxins. A later chapter addresses the significant effect on the Athabasca Delta — a UNESCO World Heritage Centre — of the W.A.C. Bennett Dam. The added drying out caused by Site C would be “history repeating itself as a rotten farce.”

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem, to continue until there is not a single Indian who has not been absorbed into the body politic,” proposed Duncan Campbell Scott, distinguished poet and deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, in 1910. In “Broken Spirit,” Warren Bell, physician, shows why Site C is “simply the culmination of a sustained process of exploitation while simultaneously eliminating Indigenous human rights.” The health of a population depends on the health of the ecosystem. Bell looks forward to “a time of global healing.”

Journalist Silver Donald Cameron shows how we can use the power of the law to get there. He tells the story of lawyer Antonio Oposa, who used the law to stop destruction of forests (the commons) in the Philippines. Cameron reveals that “Canada is one of the dozen laggard nations that refuse to recognize the human right to a healthy environment.”

Which brings us to the question of “social licence.” Reg Whiten, professional agrologist, captures the meaning of this concept, which might be defined as ongoing popular acceptance or approval by a community of the business practises that affect them. Whiten shows that in December 2017 there was a clear indication that the B.C. public never did grant the Site C Dam a social licence. He might have mentioned Justin Trudeau’s apt but empty dictum, “Governments give permits but communities give permission.”

Zoë Ducklow, in “Is Site C Really Past The Point Of No Return?” looks for meaning in Christy Clark’s well-known vow and in Premier John Horgan’s capitulation to accounting trickery that compels him to proceed with this boondoggle. The answer, of course, is No. Arlene Boon is right: “We have until the water rises to stop the dam.”

In “Broken Country,” Briony Penn discusses the cumulative impact of Site C. Environmental assessments tend to evaluate projects in isolation, neglecting connections between projects. “There is a threshold beyond which the system will lose the capacity to recover,” she asserts. Clarence Apsassin of Blueberry River agrees. “Our earth is dying. It is gradually being destroyed” — a central idea in Dr. Penn’s detailed illustrated discussion.

Now, what about that dark elephant in the room: water export? Donald Trump, high intellect of the Twittersphere, has opined that “It is so ridiculous where they are taking the water and shoving it out to sea.” Rex Tillerson, ex-CEO of Exxon-Mobil, says of the USA drought, “There is plenty of water. It’s just not all in the right places.”

The NAWAPA (North American Water and Power Alliance) scheme shows how water from west of the Rockies can be diverted eastward to quench the thirst of the American south. In Joyce Nelson’s view, the Site C reservoir becomes the last essential link in this process. According to NAFTA, impounded water is a commodity to be exported. Nelson draws on Wendy Holm’s detailed analysis to support the “diabolical thesis” that North American water is a “shared resource.”

Let’s give the last word to contributor, the late Rafe Mair (1931-2017), ex-B.C. Social Credit cabinet minister and passionate supporter of democracy, which he thinks has been violated by the corporate stranglehold on government. “The answer, I fear, for both Site C and Kinder Morgan is massive nonviolent civil disobedience.”

Read Mair’s persuasive arguments in Chapter 15 and decide what you’re going to do. Mair puts it like this:

An evil like the Site C Dam — that will flood vital food lands … trample the rights of First Nations, destroy habitat … threaten the Athabasca Delta, [and permit ] fracking — is supported by… governments and those who stand to profit from its construction.

And for some light inspiration we can perhaps recall Frank Sinatra’s “High Hopes” (1959):

Oops! There goes a million kilowatt dam![1]

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and the Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005.

*

Further reading suggestions:

Sarah Cox, Breaching the Peace (UBC Press, 2018).

Eileen Delehanty Pearkes, A River Captured (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016).

Christopher Pollon and Ben Nelms, The Peace in Peril (Harbour Publishing, 2016).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] Sinatra’s optimistic “High Hopes,” written by Sammy Cahn and James Van Heusen. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eWR3IkfHdLE

Leave a Reply