Anny of Vancouver Island gables

Heather Graham critiques Anny Scoones' meanderings and gives her blessings despite shortcomings.

September 11th, 2019

A bowling alley in Port Hardy, not Port McNeill. North Island Gazette.

A sixth book from Anny Scoones revives her wandering ways.

Island Home: Out and About on Vancouver Island

by Anny Scoones

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2019

$20.00 / 9781771512589

Reviewed by Heather Graham

*

With five titles already to her credit before the publication of Island Home: Out and About on Vancouver Island, Anny Scoones has established herself as a certain kind of writer with a certain kind of readership.

With five titles already to her credit before the publication of Island Home: Out and About on Vancouver Island, Anny Scoones has established herself as a certain kind of writer with a certain kind of readership.

Her first book, Home: Tales of a Heritage Farm, published in 2004, was followed in 2006 and 2010 by two more collections of stories about her life on Glamorgan Farm on southern Vancouver Island. All three contain illustrations by her artist parents, Bruno Bobak and Molly Lamb Bobak.

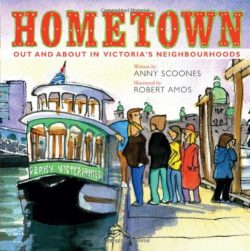

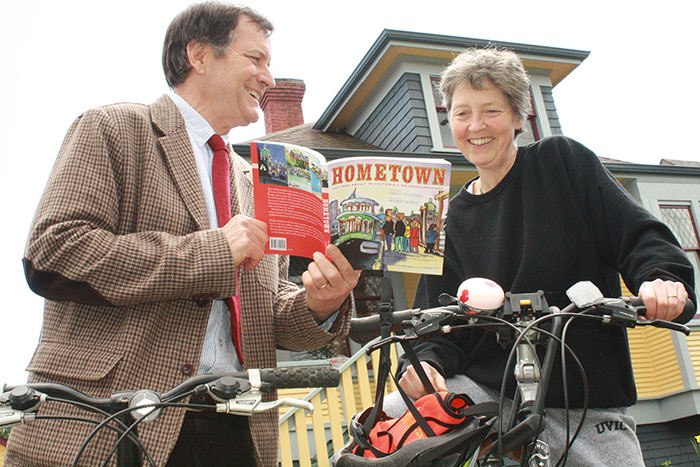

In 2013, Scoones headed in an entirely new direction. Hometown: Out and About in Victoria’s Neighbourhoods, is exactly what its title suggests: a tour through the different parts of Victoria, travelling as far as the Saanich Peninsula and Sidney with Scoones as your guide. She has left the farm behind, literally and literarily (although it will continue to pop up in her writing every now and then), and is living in the historic Victoria neighbourhood of James Bay. As for illustrations, the book includes more than one hundred original watercolours by well-known Victoria artist and writer Robert Amos. Hometown is not so much a book with pictures as it is a perfect blend of words and visuals. Stylistically, Scoones’s writing and Amos’s paintings are made for each other.

Two years after Hometown, Scoones published Last Dance in Shediac, a memoir of her mother, Molly Lamb Bobak, who had died in 2014.

*

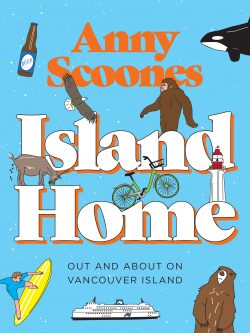

Anny Scoones latest title, Island Home, marks a return to what was so successfully executed in Hometown. In fact, their similarly worded subtitles — Out and About in Victoria’s Neighbourhoods, Out and About on Vancouver Island — seem a clear message that the books are intended as companions of a sort, the only difference being that the geographical area covered in the most recent publication is an entire island and some of the nearby smaller islands, not just one city and its neighbourhoods.

As well as having titles that resemble each other, Hometown and Island Home are similar in their narrative setup. In addition to Scoones’s account of her travels and explorations, both books contain blocks of informative text, typographically distinguishable from the main story because they are in a different font — but positioned within the body of the main story and therefore technically not sidebars — telling readers something interesting related to where she went and what she saw. Hometown used this same method, although rather sparingly, whereas Island Home positively revels in the opportunity to drop in tidbits of information and “fun facts” of various kinds: apple varieties grown on Salt Spring Island, the Pacific herring run, a brief (very brief) history of dairy farming.

Gulls and seine boats compete for herring, Qualicum Beach, March 2013. Photo courtesy of Dave Ingram

These occasional nuggets of information are not the only kind of narrative add-on to be found in Island Home. There is a second category of commentary, a more personal one, what Scoones calls “Little Thinks”: “little pauses, little daydreams, little moments to drift off and experience a gentle, relaxed thought.” Visually, these musings appear on the page in yet a third font and have a small “thought bubble” icon right at the beginning. Little Thinks are always prompted by something Scoones is writing about on her travels, and not surprisingly, they are an eclectic collection: her personal views on modern photography; an anecdote about the sixteen rescued feral cats that she took in and housed in the aptly named Pussy Barn when she was stilling living on her farm in Saanich; memories of a road trip with her mother in New Brunswick.

Not surprisingly, most of the places Scoones writes about in Island Home are south of Campbell River, the most heavily populated part of Vancouver Island; the north island gets just over twenty pages in a book of more than three hundred pages, a mere seven percent of the attention. In fact, Scoones doesn’t make it all the way to Port Hardy, the northern terminus of Vancouver Island’s highway connections: Highway 1 (the Trans-Canada Highway) from Victoria to Nanaimo, Highway 19 from Nanaimo to Port Hardy. Nor does she seem to have had any intention of going right to the end of the road, although you can’t really say you’ve done the entire island if you stop short of Port Hardy. There’s a sense that by the time she leaves Campbell River, the expedition is running out of steam. Plus the suspicion that Scoones may be out of her comfort zone: “I truly felt, with a slight anxiety, that civilization remained behind us.”

Scoones begins her peregrinations in the southern Gulf Islands, covering the usual bases as she works her way up the island – “Local Attractions Not to be Missed,” “Best Places to Eat.” A lot of ground has to be covered, and the result is a sense of clutter; there’s too much filler, especially the kind of not very exciting detail easily found in tourist brochures. It’s clear right from the beginning that objective travel reporting is never the real intention of Island Home. Wherever she goes, it’s the chance encounters, the personal challenges and discoveries, the unexpected pleasures, that Scoones wants to tell you about: her first ever camping trip; ten-year-old bakers Emma and Libby and their “amazing” cake at the annual Cumberland Foggy Mountain Fall Fair; exploring the caves at Horne Lake. A book with travelogue aspirations doesn’t really seem the best vehicle for Scoones, with her miniaturist instincts and love of the closeup. A smaller canvas, a more limited geographic area, is what suits her best: one heritage farm, as in her first three books, one small city, as in Hometown, with its focus on Victoria and environs.

Managing the three different categories of narrative in Island Home — travel reportage, information commentary, Little Thinks — might sound like it should be a fairly straightforward task, given that each one has a particular role to play and a unique appearance on the page, but the boundaries are not just fluid, they’re slippery. For starters, Scoones’s account of her perambulations is never only about what she sees and does as she travels around; for example, a visit to the museum in Cumberland, where she sees antique medical instruments, prompts her to relate, in some detail, the story of her “first alarming medical encounter.” Why is this anecdote part of the travel story and not in a Little Think?

As for the information commentary, Scoones can’t resist inserting herself into much of it, offering an opinion or a memory; the description of a trip to Spectacle Lake for a picnic is followed by some facts about the history of picnics, and right in the middle of it up pops Scoones to say, “I’ll never forget cooking chicken in foil at Cox Bay in Tofino.” One of the information blocks consists entirely of Scoones sharing with the reader her 3-B Vacation Formula (beach, book, and beverage). Yes, it’s information, but hardly what anyone would call objective, or educational (well, maybe), or historically significant.

Having said all this about “loose” categories, here’s the only question that probably matters: will most readers care if Scoones stays inside Island Home’s narrative boundaries? Will anyone fault the book for its wandering ways? Very unlikely. In a 2015 Times-Colonist review of Scoones’s fifth book, Last Dance in Shediac, Robert Amos nailed it when he identified Scoones’s “meandering” style, and her “unique and quirky voice.” Scoones excels at meandering; it’s her modus operandi. She goes where the moment leads her. The idea of adding depth to the basic travel account by including blocks of informative text was a good one in theory, and it worked fairly well in Hometown because there was a limited number of them (nineteen to Island Home’s sixty-two), but given Scoones’s penchant for straying, it probably shouldn’t surprise anyone that it didn’t turn out as planned.

As for what Amos calls Scoones’s “unique and quirky voice,” not every writer could pull off Scoones’s particular storytelling style; in other hands it would seem like an affectation, an attempt to be cute or clever. As well, there’s a certain intimate quality to the way she writes that draws the reader in, as if you’re the only person she’s telling this to, confident you’ll find it just as interesting or thrilling in the hearing as she did the actual experience itself.

Given the similarities between Hometown and Island Home, it seems clear that the publisher hopes to reproduce, in Scoones’s latest literary outing, the appeal of the earlier book, and comparisons are sure to be made. As no doubt they are meant to be. But creating expectations is always a risky strategy, because everything depends on the follow-through. A promise made but not kept won’t win you many fans.

Hometown was an unpretentious publication, but physically attractive: an uncommon 8” x 8” format softcover, full-colour covers with french flaps (also called a gatefold), always a sign that a publisher is putting money behind a title. Then there were all those wonderful watercolour illustrations by Robert Amos. Island Home is also a softcover, but of the standard 6” x 8” size used for most trade paperbacks. Its blue covers are decorated on the front with a few colour sketches rendered in a decidedly simple, even crude, style; the back cover contains just text. The only illustrations are a few black-and-white line drawings; there’s not even a photo of the author. Plus there’s no index, although that’s perhaps expecting too much in these days of diminished publishing budgets. Still, other recent titles from the same publisher have fabulous indexes. Even Hometown has an index; not a fabulous one, mind you, but definitely serviceable. At least you could find something without having to search through the entire book.

Scoones’s latest clearly falls short when compared to Hometown, but these differences are not faults, just disappointments. On the other hand, Island Home is marred by some of the most minor errors imaginable, such as the contraction “it’s” instead of the possessive “its,” or “being” instead of “been.” Small mistakes they may be, but noticeable ones all the same. An example of something missed in the process of finalizing the text involves the use of acronyms: the convention is to spell out the full name of something the first time it appears — in this case Capital Regional District — followed by the acronym in parentheses — (CRD) — and then to use only the acronym thereafter. Despite the accepted style, the full name, plus its acronym, appears three times within two pages. Island Home’s table of contents says the book contains an introduction and ten chapters, when in fact there are eleven chapters: tucked between “Ladysmith and the Road North to Nanaimo” and “Driving Up-Island” is “Nanaimo to Nanoose.” What could possibly explain such an omission from the table of contents? As for accuracy, Port McNeill will be very surprised to learn that it has a bowling alley (it’s actually in Port Hardy) and a Canadian Tire store (no such shopping opportunity north of Campbell River).

The publisher obviously had its own reasons for not wanting to invest time and money in Island Home — perhaps other titles had more sales potential or were a more prestigious addition to its list — but surely every book, no matter how humble, deserves basic scrutiny before being sent on its way. Or is this apparent lack of interest an indication of something more significant at play, such as the end of the Scoones franchise? Hopefully not. Like every good teller of tales, Scoones knows that the world is full of stories, and there will always be an audience for the kind of tale she tells, with its rambling ways and quirky charms. “Quirky” is not a technique you can learn in creative writing classes; it’s a gift, and she has it.

So don’t stop now, Anny Scoones. Break a trail, and readers will follow.

*

Heather Graham worked as an editor for nearly thirty years, and during that same time made more than one foray into the seductive but fraught business of bookselling. Now officially retired, she indulges her bookish inclinations by taking on the occasional editing project, as well as trying her hand at the storytelling process itself and doing some of her own writing. She lives on Malcolm Island in Queen Charlotte Strait.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply