#230 A good year and a good man

January 10th, 2018

Green Mackinaw in Europe, 1954-55.

Alfred H. Siemens

Victoria: Friesen Press, 2017.

$25.99 / 9781460295342

Reviewed by Graeme Wynn

Green Mackinaw recalls the “brief shining time” that its author spent in Europe in the 1950s. Alfred Siemens, a UBC student in his early twenties, crossed the Atlantic in the fall of 1954 to study at the University of Hamburg. He returned to Canada in July 1955. In the intervening months he made new friends in Europe and (after two rich and full weeks in England, en route) travelled widely, through Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Greece, Crete, the former Yugoslavia, and Austria.

Green Mackinaw recalls the “brief shining time” that its author spent in Europe in the 1950s. Alfred Siemens, a UBC student in his early twenties, crossed the Atlantic in the fall of 1954 to study at the University of Hamburg. He returned to Canada in July 1955. In the intervening months he made new friends in Europe and (after two rich and full weeks in England, en route) travelled widely, through Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Greece, Crete, the former Yugoslavia, and Austria.

Fascinated by people, the countryside, buildings, and galleries, and an avid photographer as well as a dutiful diarist, he created a detailed record of his time abroad. Fifty-five years later, Siemens dusted off his diary, scanned long-ignored slides and — in an admitted act of self-indulgence — began to compile this account as a gift to family and friends. If this sounds like a recipe for sweet nostalgia, be warned. It is far from that.

Mary Karr, whose bestselling memoir The Liar’s Club, published in 1995, did much to elevate the genre to its current popularity, notes in her more recent The Art of Memoir, that the most effective memoirists “sound on the page like they do in person.” Siemens achieves this. I know because we were colleagues in the UBC department of Geography for twenty years until Siemens retired in 1997; we had broadly similar interests, taught courses jointly, and went on field excursions together.

Clearly I am in contravention of George Orwell’s dictum, that reviewers should have no acquaintance with the authors of books they appraise because personal feelings get in the way of proper critical assessment. Be that as it may, I learned a lot of positive things from this book, about the art of the memoir, about my former colleague, and about that most complex and enduringly fascinating of topics — how lives are lived and understood.

Moments of discovery and delight are common in the pages of Green Mackinaw, but this is no mere collection of sentimental yearnings for the (imagined) golden days of youth. It reflects on the writer’s experience, not simply to recall it but to rediscover, reinterpret, and represent it in ways that hold wider meaning.

Sometimes circumstances suggest connotations: Siemens takes a soon-to-be-scrapped passenger liner across the Atlantic in 1954 and returns by air; old ways are replaced by others that carry “the lustre of newness.” Sometimes the symbolism is evident yet subtle. “Green Mackinaw” refers to the plaid woollen cloth jacket that Siemens acquired in B.C. and left, well-worn, in a “re-use” bin in Hamburg; part, at least, of the identity signalled by this archetypal Canadian piece of attire was sloughed off in Europe — and at least a little of Canada remained in the minds of some Germans when Siemens took his leave.

Prairie-born Alf Siemens grew to adolescence on a farm near Namaka, Alberta, before his family relocated to the Fraser Valley in British Columbia. Raised in an evangelical branch of the Mennonite church, he was the first among his kin to attend university. At UBC he enrolled in Arts courses (among them world political history, settlement geography, and the history of art, that would be important to his European adventure), but as a keen member of the Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship (he was twice President while an undergraduate) he had his “Christian spirituality immensely enhanced,” during his first two (pre-Hamburg) years at UBC.

In England en route, and on arrival in Hamburg, the VCF and the Mennonite church offered immediate points of connection and warm friendships. Before long he was teaching a Mennonite children’s Sunday school on the outskirts of Hamburg. Devout, earnest, even self-righteous, he aspired to be “an effective Christian, one who would finally ‘lead others to Christ’” (p. 69).

In the 1950s, religious belief was generally more profound and pervasive than in our own secular age, but a striking religiosity permeates the diary upon which much of Green Mackinaw rests. Heading south from Hamburg in February 1955: “I am on my way again… alone but not at all dismayed because … He goes with me” (p. 79). After the inevitable trials and tribulations of solo travel on a miniscule budget, a chance meeting, in Greece, with a fellow traveller earlier encountered in Italy yielded the entry: “Prospects are good. How fortunate to have a heavenly Father!” (p. 111).

Yet one of the strengths of this memoir lies in its author’s willingness to reflect on his pious younger self. Some of what he rereads seems to be “embarrassing hocus pocus from my present perspective” (p. 107); some of the entries, he concludes, reflect the gaucherie of youth; some amounted to priggish judgments, “censorious, stand-offish, holier-than-thou” opinions of an uncompromising believer and sanctimonious soul.

In the end it is clear that some of the foundations of this strong belief were shaken in Europe. Mennonite strictures against alcohol were put to the test (and failed – though “boozing” remained beyond the pale of acceptance). Contemptuous of a Hamburg professor’s challenge to the Creation story — it was not logical, wise, or even practical to close one’s mind to the supernatural — Siemens nonetheless admitted to the diary that lessons about the great age of the earth “no longer seemed as ridiculous” (p. 178) as they had a year or two earlier.

A decade or so on, conviction had been further and considerably softened by graduate study (in Wisconsin) and fieldwork in Mexico. “The erosion of faith was not deliberate, it happened with the wind and the rain” (p. 61). Sincere in its day, much of the diary’s “godly talk” appears to its author, sixty years on, as a form of evasion.

Described as about six hundred pages of “scribble,” the diary is quoted often but sparingly here. A few of the entries are of the sort one might expect of “an innocent abroad,” turning on clichés and veering to the banal. Others reveal a certain earnestness, typical perhaps of the colonial confronting the avowed masterworks of his/ her civilization. Thus, of Michelangelo’s statue of Moses, viewed “carefully, from various angles to perceive some of its meaning and significance:” this is a figure “of an elderly man, still very hale and hearty, with a mature and disapproving opinion of what went on around him” (p. 98).

The young Siemens was arguably at his best characterizing town and countryside. Here he is in Creglingen, east of Heidelberg, enjoying “the harmony of the streets, the gossiping of women at doorways, the scamper of fowl and of children, and the very lovely chime of the church bell, a sweet smalltownish chime” (p. 189). Birds in egg. Much of Siemens’ academic career was devoted to the description and interpretation of landscapes.

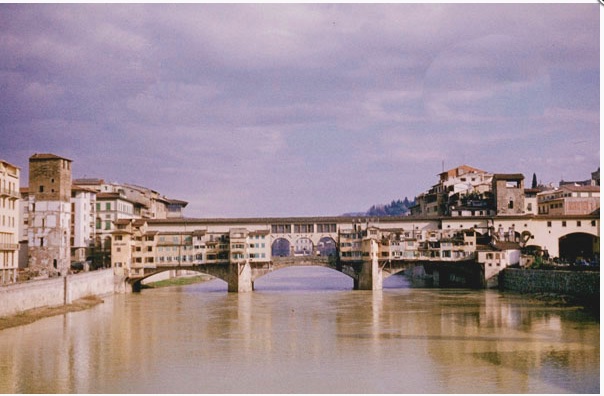

Photographs were essential to this academic practice, and many of the images that abound in this book are themselves small marvels. Made with a simple 35mm camera, they have been groomed and manipulated with modern computer software. Cropped, enhanced, blemishes removed, and colour palettes adjusted, they are testaments to Siemens’ sharp visual sense that offer a striking and valuable record of Europe less than a decade after the Second World War.

Here new views of familiar landmarks (the Acropolis, the Coliseum, the tower and basilica in Pisa) delight, alongside pictures of lesser structures, locals going about their everyday business, and — reflecting the diligent student’s fascination with galleries and museums — renditions of famous works of art, little seen wood carvings, and so on. Text and images work together here to provide what Mary Karr regards as the sine qua non of the successful memoir, “the sheer convincing poetry of a single person trying to make sense of the past.”

The final pages of this book recount Siemens’ homeward journey. High above the Atlantic, passengers on the Icelandic Airlines’ DC4 were served dinner, and then coffee and cognac. “It seemed,” he concludes in the very last sentence of his memoir, “immensely civilized.”

Indeed. After the intellectual challenges (classes in Hamburg were much different from those at UBC), the material hardships (the frequent shortage of funds on the Mediterranean journey foremost among them), and the emotional turmoil (being far from home after his parents were injured in an automobile accident) of his foreshortened year abroad, Siemens surely appreciated this moment to relax and remember.

His German exchange had been brimful with new experiences. It consolidated his early education, expanded his horizons, and clarified his academic interests (helping him to identify a rewarding career path). It is for just such reasons that we encourage young people to embark on similar programs today. That the young Mennonite found an after–dinner brandy “civilized” also reminds us that relocation worked its spell by unsettling easy orthodoxies and putting accepted dogma to the test of experience.

Though he would return to lead UBC’s Varsity Christian Fellowship with distinction, Siemens was changed by his time in Europe. His humble, unpretentious effort to understand how past and future were refracted in that pivotal moment tells us much about a good year in the life of a good man, and offers — as any valuable memoir should — thought for further reflection of the roles of character and circumstance, chance and change in shaping human lives.

*

Seen here preparing to write another piece for The Ormsby Review, Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he is currently President of the American Society for Environmental History, and Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The Ormsby Review and in 2018 he will join the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature|History|Society series published by UBC Press, and 2018 will see the appearance under UBCP’s On Point imprint, of a collection of essays, co-edited with Colin Coates, on The Nature of Canada.

Seen here preparing to write another piece for The Ormsby Review, Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he is currently President of the American Society for Environmental History, and Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The Ormsby Review and in 2018 he will join the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature|History|Society series published by UBC Press, and 2018 will see the appearance under UBCP’s On Point imprint, of a collection of essays, co-edited with Colin Coates, on The Nature of Canada.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply