#57 F.W. Howay

January 21st, 2016

LOCATION: New Westminster Public Library, main branch, 716 6th Avenue, New Westminster,

The most distinguished chairman of the first public library in British Columbia, the New Westminster Public Library, was author and lawyer Frederic William Howay, the most important collector of local literature in the first half of the 20th century. F.W. Howay was a giant of northwest coast history and literature, but few know his name today. Howay co-wrote a standard history of British Columbia that was widely used until the 1950s. The first article in the first issue of the British Columbia Historical Quarterly, in January of 1937, was written by Howay, the primary authority on many facets of B.C. history during his era.

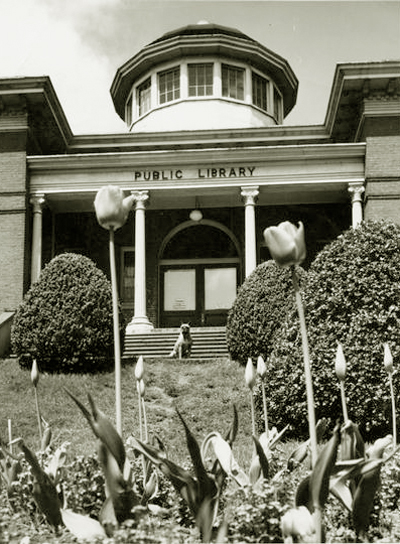

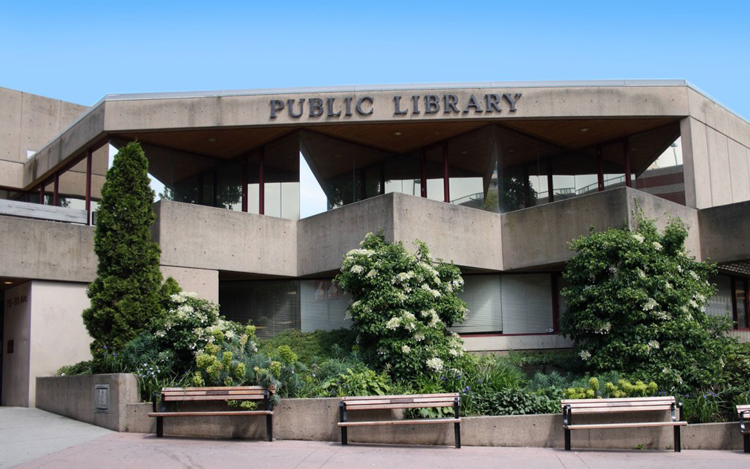

The first library building in New Westmister was built on Columbia Street in 1892 and destroyed by the great fire of 1898. The Carnegie Foundation provided funds for the “Jennings” Old Carnegie Library that operated behind the Court House from 1905 to 1958. To coincide with the 100th birthday of British Columbia, Governor-General Vincent Massey opened a new New Westminster Public Library building in 1958 at 6th Avenue and Ash Street. An extensively renovated version of the library was re-opened in 1978. The NWPL’s first branch library in 148 years was opened in 2013 as part of the revitalized Queensborough Community Centre.

QUICK ENTRY:

Frederic William Howay was born near London, Ontario, in 1867 and brought to B.C. as a child. With his lifelong friend Robie Reid and future B.C. premier Richard McBride, Howay entered Dalhousie University to study law in 1887. He graduated in 1890 along with Richard McBride and another future premier of British Columbia, W.J. Bowser.

Howay returned to B.C. and opened a joint legal practice with Reid in 1893. The first article in the first issue of the British Columbia Historical Quarterly in 1937 is by Howay, a longtime supporter of the publication. Howay co-wrote a four-volume history, British Columbia from the Earliest Times to the Present (1914), with E.O.S. Scholefield, followed by British Columbia: The Making of a Province (1928), effectively replacing Hubert Howe Bancroft’s history for four decades.

Howay was the first president of the B.C. Historical Association, the B.C. representative on the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and a member of the Art, Historical and Scientific Association of Vancouver. He was also a longtime Freemason who hobnobbed with the upper class as a member of both the Terminal City Club in Vancouver and the Pacific Club in Victoria. Howay was narrowly defeated in a 1906 election as a Liberal candidate running against his friend, Premier Richard McBride, and was appointed Judge of the County Court of New Westminster in 1907. He would serve as a county judge for 30 years, severely intolerant of labour unrest, until he retired in 1937.

Howay was continuously engaged as a maritime historian, and as B.C.’s most active regional scholar he was elected as president of the Royal Society of Canada in 1941. He was a UBC Senator from 1915 to 1942, first chairman of the New Westminster Library and a recipient of the King’s Silver Jubilee Medal. He was a good friend and benefactor of William Kaye Lamb who inherited Howay’s mantle as the foremost archivist of British Columbia’s literary culture. He died in New Westminster in 1943. His private collection of literature and papers was donated to UBC where it remains, in conjunction with the valuable collection of Robie Reid.

FULL ENTRY:

The most important collector of local literature in the first half of the 20th century, Frederic William Howay, also co-wrote a standard history of British Columbia that was widely used until the 1950s. Appropriately the first article in the first issue of the British Columbia Historical Quarterly in January of 1937 is by Howay, the primary authority on many facets of B.C. history during his era. He was a longtime supporter of the publication, providing articles such as The Origin of the Chinook Jargon (Vol. VI, No. 4, pages 225-250). He had earlier contributed to the Canadian Historical Review such articles as “Indian Attacks upon Maritime Fur Traders of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1805 (VI, December, 1925). Historian Chad Reimer has estimated in Writing British Columbia History, 1784-1958, that Howay published some 300 books, articles, addresses and reviews on Northwest Coast history.

F.W. Howay was born near London, Ontario November 25, 1867–the year of Confederation–and was brought to B.C. as a child, first to Clinton in 1870, and then to New Westminster in 1874, after his father had first come west in 1869. Familiar with the pioneering exploits of his father-in-law William Ladner as a boy, Frederic Howay (born as Howie) had a penchant for history from an early age. He attended school in New Westminster and wrote his Provincial Teachers’ examinations in Victoria in 1884. He taught school at Canoe Pass near Ladner in 1884, then taught at nearby Boundary Bay. During this period he enrolled in McGill University’s Associate of Arts Program but was unable to complete his studies due to lack of funds. A wealthy uncle intervened. With his lifelong friend Robie Reid and future B.C. premier Richard McBride, Howay was able to enter Dalhousie University to study law in 1887. “Its law program,” notes Chad Reimer, “was the British Empire’s first university-based common law school. Established in 1883 as a departure from the practitioner education then dominant, the program sought to establish law as an academic pursuit, focusing on library research and seminar discussions.” While in Halifax, Howay began writing articles on law, politics, temperance, and noteworthy British Columbians for periodicals in B.C. He graduated in 1890 along with Richard McBride and another future premier of British Columbia, W.J. Bowser.

Howay was admitted to the B.C. bar in 1891 and opened a joint legal practice with Reid in 1893. Also in 1891, he began a fifteen-year term as secretary of the New Westminster school board. Social service went hand-in-hand with his ardent belief in the value of popular history. He was the first president of the BC Historical Association, the B.C. representative on the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and a member of the Art, Historical and Scientific Association of Vancouver. He was also a longtime Freemason who hobnobbed with the upper class as a member of both the Terminal City Club in Vancouver and the Pacific Club in Victoria.

Howie was narrowly defeated in a 1906 election as a Liberal candidate and was appointed Judge of the County Court of New Westminster in 1907, possibly as his reward for having run against his friend, Premier Richard McBride. He would serve as a County Judge for thirty years until he retired in 1937.

In 1914, with E.O.S. Scholefield, Howay published a four-volume history, British Columbia from the Earliest Times to the Present, that effectively replaced H.H. Bancroft’s work as the standard history of the province. The work reflected Howay’s staunch affinities with the “builders” of British Columbia, such as coal baron Robert Dunsmuir, whom Howay praised as a “pioneer of pioneers.” As a judge, he could be severely intolerant of labour unrest but he was not without his progressive viewpoints. “Unlike the Edwardian historians,” writes Chad Reimer, “Howay acknowledged that Natives had been the first occupants of the region, and he pushed Scholefield to include a chapter on Native peoples at the beginning of Volume 1 of British Columbia because ‘they were here first.'” His views on Asiatic labourers (“little yellow men”) were, however, narrowly racist.

Howay was continuously active as an historian and community builder, serving as president of organizations such as the Historic Sites and Monuments Board and the Champlain Society. He received many honours as B.C.’s most active regional scholar, culminating in his election as president of the Royal Society of Canada in 1941. He was also a UBC Senator from 1915 to 1942, first chairman of the New Westminster Library and a recipient of the King’s Silver Jubilee Medal.

Howay’s second history of British Columbia, published in 1928, eclipsed his previous work and remained the standard source until the 1950s. He was a good friend and benefactor of William Kaye Lamb who inherited Howay’s mantle as the foremost archivist of British Columbia’s literary culture. He died in New Westminster on October 4, 1943. Notification of his election as a Fellow of the American Geographical Society was received after his death.

A bronze plaque in his memory was placed at the Clarkson Street entrance to the New Westminster Courthouse on November 26, 1943. His private collection of literature and papers was donated to UBC where it remains in UBC Special Collections, in conjunction with the valuable collection of Robie Reid. F.W. Howay was a giant of B.C. history and literature, but few today know his name.

“Jennings” Old Carnegie Library that operated behind the New Westminster Court House from 1905 to 1958.

BOOKS:

Howay, F.W. & E.O.S. Scholefield. British Columbia from the Earliest Times to the Present (S.J. Publishing, 1914).

Howay, F.W. The Early History of the Frazer River Mines (Archives of British Columbia, Memoir No. VI, printed by Charles F. Banfield, Victoria, 1926).

Howay, F.W. British Columbia: The Making of a Province (Ryerson Press, 1928)

Howay, F.W. Builders of the West: A Book of Heroes (Ryerson Press, 1929)

Howay, F.W. The Dixon-Meares Controversy (Ryerson Press, 1929. Editor.

Zimmerman’s Captain Cook, 1781 (Toronto: Ryerson, 1930). Editor.

Howay, F.W. A List of Trading Vessels in the Maritime Fur Trade, 1820-1825 (Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada, 1934). Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Third Series, Section II. Vol. XXVIII

The Journals of Captain James Colnett Aboard the Argonaut from April 26, 1789 to November 3, 1791 (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1940). Editor. This book includes ‘A translation of the Diary of Estevan José Martínez from July 2 till July 14, 1789’. Editor.

Howay, F.W., ed. Voyages of the Columbia, to the North West Coast, 1787-1790 and 1790-1793 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1941).

Howay, F.W. & W.N. Sage and H.F. Angus. British Columbia and the United States: The North Pacific Slope from Fur Trade to Aviation (Ryerson, Yale University Press & Oxford University Press, 1942).

Howay, F.W. & Richard A. Pierce. A List of Trading Vessels in the Maritime Fur Trade, 1785-1825 (Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press, 1973).

Noel Robinson wrote the following tribute in the January of 1944 to mark the death of Judge William Howay (1867-1943), former president of the BCHF (from British Columbia Historical Quarterly, 1944)

In paying tribute to the memory of my old friend Judge Howay I do so with the feeling that anything I may write will fall short of what I should like to write, for he occupied a unique niche in my esteem and affection for a period of about thirty years.

Widely known though he was in Canada, and particularly British Columbia, as jurist, historian, and lecturer, there will be many, even among the readers of this Quarterly, who did not know him intimately. It is for these, particularly, that I would endeavour to paint a little pen-picture of one who was not only an outstanding Canadian, but a very lovable and intensely interesting and versatile man.

It is as I knew him during the innumerable afternoons and evenings I have spent with him in the delightful study of his home in New Westminster that I shall always remember him best. Many walls of his home in New Westminster were hidden with shelves of books from floor to ceiling, but it was in this sanctum, the windows of which afforded a spacious view of the great Fraser River far below, where he was surrounded by the pick of his priceless collection of British Columbiana, as well as his more intimately prized volumes of prose and poetry, that he always seemed most at home. There, and in his summer home up the North Arm of Burrard Inlet, where he was an equally happy host, and where I was able to appreciate his talent in backwoods lore – yes, and as a cook and very practical skipper of his motor-launch.

In that room, less than two weeks before he died – he played me two games of chess upon the old chess board that showed signs of its immersion when, upon one occasion, his launch shipped a sea which poured into the cabin while he /p. 16/ was playing a game. That afternoon we “boxed the compass” in conversation for the last time upon those literary matters that were so dear to him. His mentality was unimpaired, but we were both aware that he had, in all human probability, received an intimation of the approaching end. It was characteristic of him that this knowledge made no difference to the zest with which he engaged in those games – both of which he won – or in the discussion that followed. He may be said to have died, as he would have wished, almost with his boots on.

He was at that time preparing a programme for the New Westminster Fellowship of Arts, of which he had been the moving spirit for a quarter of a century, and the interests of which, together with those of the Vancouver Dickens Fellowship, of which he was life Honorary President as well as a Vice-President of the parent Fellowship in England, were very close to his heart. This winter the subject of study of the Fellowship of Arts is the Scandinavian countries, their peoples and history, and the Judge had saturated himself in the lore of the Vikings and the prose and poetry of their descendants.

He had an almost phenomenal memory for prose and verse, and this was never more apparent than upon that afternoon, when he quoted to me from memory stanza after stanza of ballad poetry dealing with early Viking history and feats of arms. In the midst of one of these quotations he was reminded of Napoleon’s connection with Scandinavia (Bernadotte). He had a whole shelf of his library devoted to Napoleon, and a picture of the Little Corporal stood upon his mantelshelf. Apropos of this digression he recited a rolling Napoleonic balled.

Judge Howay, as his friends well knew, and as befitted an historian, had a passion for accuracy. There was hardly one among his historical books dealing with British Columbia and Northwest America that was not profusely annotated. His mind was so well stored, too, with general historical data that, no matter what knotty problem came up for discussion, he would get up from his chair, remove his pipe from between his lips, with the remark: “I think we can find something on that,” and, walking to his shelves, would take down a book, turn the pages, and with: “Yes, here it is,” read an extract bearing upon the point at issue.

Though a man of less than medium height, Judge Howay was possessed of a cast of countenance, a dignity, and a mode of expression that, in some indefinable way, seemed to add to his stature and impressiveness upon occasion. At other times his fresh complexion, the snow-white curl upon his head, his keen, sometimes quizzical eyes, and the pipe between his teeth, would give him quite a Dickensian air. I can see him now at the annual Twelfth Night revels of the Fellowship of Arts (which are always in the costume of the period being studied), made up as Mr. Pickwick, or dancing Sir Roger de Coverley, his ermine robe flying, his crown awry, when he had impersonated King Henry the Eighth.

In my mind’s eye I can see him, too, very vividly, in tail silk hat and frock coat year after year among the worthies of New Westminster at the historic crowning of the May Queen of the Royal City, a ceremony that has taken place for seventy years. For years he wrote the addresses to be spoken by the May Queen and the May Queen – elect– right down to the last year of his life, when he happened to be away in Eastern Canada, and delegated that pleasurable duty to me.

He was so saturated in the literature and lore of England, from Chaucer, through the Elizabethan ear, the prolific age of Anne and onwards; so familiar with the atmosphere of the countryside there, its castles, cathedrals, abbeys, and manorhouses, that it was sometimes difficult to realize that, though he had travelled widely upon the American continent and in Hawaii, he had never visited the Old Country. His intimate acquaintance, through reading, with all the places Dickens has made familiar to his readers and peopled with his characters was encyclopedic, and he was heard at his best in those little cameo-like talks, so full of acute judgement and wit, which he delivered annually to the members of the Vancouver Dickens Fellowship.

Many years ago, as a youth, I found myself reporting a case in court at Worcester, on the Oxford Circuit, when Sir Henry Fielding Dickens, notable son of Charles Dickens, was either counsel for the prosecution or the /p. 17/ defence. If I remember correctly he, too, was a comparatively small man, and his mode of expression and witticisms were recalled to me many years later by similar characteristics in Judge Howay.

Upon this occasion a dinner was given by the mayor and aldermen of Rocky Mountain House in Judge Howay’s honour, and it was preceded by a cocktail party at the mayor’s home. At that party the Judge was greatly attracted by a small statuette of a Kentucky colonel. The mayor pressed him to accept it as a memento of his visit, but the Judge demurred. There upon His Worship whipped off the head of the “colonel” and took from the interior a bottle of whiskey, with the remark: “Well, Judge, if you won’t accept the gentleman as a whole you shall certainly sample part of him.” But Judge Howay was a teetotaller!

His love of the sea and ships, and his knowledge of the latter, their construction, and their rigging in the days of sail, was particularly intimate for a landsman. I like to remember how he revelled in recalling the days of Drake and the Spanish Main, and the voyages and explorations of Captains Cook and Vancouver. In connection with the two latter, much valuable material was published from his pen as a result of his researches. For many years he visited Boston annually to dig into the archives of the Massachusetts Historical Society for data regarding the early fur-trading on the North American coast.

This is a reminder that he was as well known in historical circles of the Northwest on the other side of the border as he was in Canada, and that he was the recipient of several honours from historical bodies there. In a recent issue of this Quarterly he paid tribute to the memory of a distinguished historian on the American side of the line, Mr. T. C. Elliot, one of his oldest and closest friends, whose work he admired greatly.

Let me carry the reader back half a century or more in the life of Judge Howay. I have before me as I write a paragraph, yellow with age, which was found among his newspaper cuttings. It is from the columns of the British Columbian of New Westminster of about 1890 and was written when the Judge, as a very young man, was about to enter upon his professional career in the Royal City. It is worth printing in full:

Mr. F.W. Howay, a graduate of Dalhousie Law School, who has recently returned home after making a very credible record in his examinations, has opened a law office in McKenzie St. No. 17, near to Mr. Whiteside’s office, and intends to practice his profession in the city, upon which, in common with Ruskin and Dockrill, he has reflected an appreciable honor in his college career. Mr. Howay is only a boy in appearance, but he has shown that there is the right sort of material there. He is on the first round of the legal ladder but hopes to climb to fame through perseverance. And he will probably do it.

How right the author of that paragraph proved to be in his forecast.

In closing this tribute may I add I have never known a man who possessed in quite so marked a degree the judicial capacity combined with so strong a vein of sentiment—his emotions were very near the surface, especially in later years—pronounced sense of humour, and genius for friendship as Judge Howay. To quote his favourite author, Charles Dickens—it will be easy to keep his memory green.

— Noel Robinson, born 1879, was a Vancouver Columnist for newspapers that included the Vancouver World, Star and Province. He contributed historical articles and received a Good Citizen award in Vancouver for his work with organizations that included the museum society, Little Theatre and the B.C. Historical Society. He co-wrote Blazing the Trail Through the Rockies, the Story of Walter Moberly and His Share in the Making of Vancouver. Robinson died in 1966.

British Columbia Historical Quarterly, January 1944

We are Brogdingnag: Rear View Mirror #1

“And if you will take the trouble to follow carefully the course of the good ship “Adventure” as recorded by the voracious, if not veracious, traveller, Captain Lemuel Gulliver, you will find that his land of Brobdingnag was in this very latitude, and if you examine the map which is to be found in the early editions you will conclude that it could have been none other than our own Island of Vancouver. “– F.W. Howay

—————–

INTRO BY ALAN TWIGG

ONCE UPON A TIME our province was in dire need of a journal that would present its burgeoning history on a literary plane. So the most important collector of local literature in the first half of the 20th century, Judge Frederic William Howay co-created the British Columbia Historical Quarterly in 1937. Here is the first article in the first issue, written by Howay, who co-wrote a four-volume history, British Columbia from the Earliest Times to the Present (1914), followed by British Columbia: The Making of a Province (1928). It’s Howay’s presidential address at the first annual meeting of the B.C. Historical Association on October 12, 1923.

—

I wish on this occasion to trace in a general way and as interestingly as possible the earliest clays of our Province, to Strive to show that we had a story before the advent of the Canadian Pacific Railway, that we had a story before the days of Caribou and its wondrous gold wealth—yes, that we had a story before the foot of Hudson’s Bay trader or Nor’ West trader ever trod our soil. Not only so, but also that this story of our birth and infancy is just as interesting and romantic as that of our adolescence. I desire in this connection to stress the great influence exerted upon our story by the search for two things——the search for the North-west Passage and the search for the sea-otter.

The clouds of doubt and darkness that from the beginning of time had rested upon the western coast of North America found their last abode within the confines of the Province of British Columbia. The search for the North-west Passage lifted these clouds for an instant; the search for the sea-otter dispelled them altogether.

Long before the days of Columbus many dreamed of a navigable water communication between Europe and China after 1493 this became a fundamental tenet of geography. With the increase of geographical knowledge the great island-studded ocean, which in the early maps occupied the space where is now the Continent of North America, gradually dwindled down into a mere strait, the Strait of Anian, or the North-west Passage, as it was commonly called. But as a strait it persisted. And the mere fact that it did not exist in any particular latitude in which the geographers had placed it was held to be no proof of its non-existence; but only proof of its non-existence in that place. In fact, it was a kind of peripatetic waterway whose location depended, as Sam Weller would have said, “upon the taste and fancy” of the geographer. Finally, the poor strait was driven clear off the map of the Atlantic Coast, but that did not dispose of it. It must exist; and if it did not reach the Atlantic Ocean, it must enter into Hudson or Baffin’s Bay.

We turn now to the Pacific Ocean side. In 1579, Sir Francis Drake. the freebooter, had ravaged and pillaged the coast from Chili [sic] to Mexico. With the hold of the “Golden Hind” filled with treasure, he feared to return to England by way either of Cape Horn or of the Cape of Good Hope, lest he should he captured by the Spaniards. He determined to sail home through the North-west Passage. Of course, the effort was unsuccessful. Drake reached, in this search, perhaps 48°, certainly 43°. Ink enough to float the “ Golden Hind” has been spilled in the discussions as to his extreme point.

The only spot left for this poor hunted strait, then, was north of Drake’s limit; so it, like a hunted hare, found refuge for years right within our boundaries. Some of the early maps of the 1600’s and 1700’s show this region as vast sea; others show it as a collection of islands; others again show it as a wide strait; while others show it as containing two or even three straits. Naturally, the spot became a favourite with romancers. Bacon, that wisest and that meanest man. selected it as the location of his ideal land of Atlantis. And if you will take the trouble to follow carefully the course of the good ship “Adventure” as recorded by the voracious, if not veracious, traveller, Captain Lemuel Gulliver, you will find that his land of Brobdingnag was in this very latitude, and if you examine the map which is to be found in the early editions you will conclude that it could have been none other than our own Island of Vancouver. In this neighbourhood, also, three persons at least claimed that they had found and sailed through a North-west Passage—Maldonado, de Fonte, and de Fuca. It is not my purpose to enter into any details of these alleged voyages. Maldonado’s was always regarded as a false tale; de Fonte won belief for a few years. but later he also was found to be false; but de Fuca, for some unaccountable reason, has had believers in his story up to the present clay. He was a more fortunate liar than either of the others, that was all. Either the geography of our country has changed wonderfully since he sailed across and through time great barrier range of the Rocky Mountains and the vast prairies, or else the voyage was never made and is naught but the baseless fabric of a dream. And his supporters may take whichever horn of the dilemma they may think the more softly cushioned.

Aside from Drake’s voyage, two nations only, until 1778, gave any attention to the coast-line of the Pacific—Spain and Russia. Vastly different reasons were operating in their respective cases. Spain’s only interest was in obtaining information of the existence of harbours that might furnish refuge to the treasure-ships from the

Philippines. Beyond that, she neither wished to know nor to have any other nation discover what lay hidden under the mists of the North….

—

This article is part of an ongoing series of looks into the Rear View Mirror of the past that is presented by our colleagues at British Columbia History, the province’s most venerable literary periodical, dating back to 1937. As the journal of the B.C. Historical Federation, BCH is published quarterly in March, June, September and December. It provides feature-length articles as well as documentary selections, essays, pictorial essays, memoirs, and reviews relating to the social, economic, political, intellectual, and cultural history of British Columbia. British Columbia History began in 1923 as the Annual Report and Proceedings of the British Columbia Historical Association (now the British Columbia Historical Federation). From 1937-58 it was published as the British Columbia Historical Quarterly. From 1965-2005, it was called the BC Historical News. The BCHF is fortunate to have the support of the UBC Library in digitizing the back issues of its publications and supporting the stewardship of these important links to the past. To access the material directly, click on http://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/pdfs/bchf/1st_bcha.pdf

Leave a Reply