#555 Arthur Erickson’s steel house

May 31st, 2019

Eppich House II: The Story of an Arthur Erickson Masterwork

by Greg Bellerby, with an introduction by Michelangelo Sabatino

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2019

$45.00 / 9781773270470

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

This is the second volume in a series edited by Geoffrey Erickson and authorized by the Erickson family. (The first was Francisco Kirpacz: Interior Design (Figure 1, 2015), written by Arthur Erickson himself). Geoffrey Erickson is also credited with many of the stunning photographs that illustrate this lavishly produced monograph. The design, by Naomi MacDougal, artistically responds to the curvilinear aesthetic of the subject at hand, Arthur Erickson’s house for Hugo Eppich and his wife Brigitte.

This is the second volume in a series edited by Geoffrey Erickson and authorized by the Erickson family. (The first was Francisco Kirpacz: Interior Design (Figure 1, 2015), written by Arthur Erickson himself). Geoffrey Erickson is also credited with many of the stunning photographs that illustrate this lavishly produced monograph. The design, by Naomi MacDougal, artistically responds to the curvilinear aesthetic of the subject at hand, Arthur Erickson’s house for Hugo Eppich and his wife Brigitte.

Prof. Michelangelo Sabatino, a specialist in Canadian Modern architecture and Erickson in particular, provides a brief foreword to the book, noting the significance of this commission within the broader North American context. He mentions for instance Barton Myers’ steel and glass Wolf House (1972-4) in Toronto and Meis’s Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (1945/51) as precedents.

The main text, four chapters, is a compilation of quotes from previously published commentaries and interviews skillfully assembled by author Greg Bellerby to take the reader through the story, from the design history to the finish and furnishing of the house. Sources include published interviews with Erickson himself; comments by Hugo Eppich, the client, and Nick Mlikovich the project architect; and interviews with Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, the landscape architect. Observations by Erickson contemporaries such as Barbara Shapiro, Nick Milkovich, Bruno Feschi, Bing Thom, Cornelia Oberlander, and Hadani Ditmars are drawn from various publications. Together with the illustrations the text reads like an extended conversation.

The Eppich brothers, Helmut and Hugo, immigrated to Canada in the early 1950s from Slovenia. Trained as metalworkers, they built Ebco, one of one of Canada’s largest and most successful machinery fabricators. One of their boring machines excavated the guide tunnel for the English Channel Tunnel. Erickson would provide houses for both families, each a very unique response to similar site conditions.

A summary of Erickson’s domestic design work opens with his West Coast Modern post-and-beam residences (Smith House 1953, Stegman 1954, Baldwin 1963) and takes us through this conceptual evolution of the plan and form as he moved through various approaches to landscape siting (Killam-Massey House 1955, second Smith House (1964) and materials (Grauer pool cabana in plexiglass (1957), Filberg House in exposed rock and filigree metalwork screens (1958).

The first Eppich House, for Helmut and Hildegard in 1972, responded to two requests: permanent materials and a setting for a collection of painting and sculptures. These art works were the legacy of a third brother, the accomplished German artist and critic, Egon Eppich. The nominal budget was $90,000 but the architect had “a free hand.” The location was a steep sloping site in West Vancouver with a creek running through it. It was Erickson’s first concrete house. As the authors demonstrate, for the design solution Erickson reached back not only to his timber post-and-beam West Coast Modern portfolio but to also the more monumental corporate work in glass and concrete. This included the bold geometric forms of the MacMillan Bloedel building and rhythmic trabeated elements of the Museum of Anthropology, also on the desks of Erickson’s firm at this time. The result was a monumental structure that took the modernist tradition of West Coast design principles to a new level of both abstraction and physical presence.

Eppich II, for Hugo and Brigitte, is a different story although the building site, two steep lots with a meandering creek in West Vancouver, was similar to Helmut’s. Designed in 1979, the house was not finished until 1988. In the meantime Ebco had emerged from the brutal early 80s financial recession and was now capable of building advanced technologies such as TRIUMF, the worlds largest cyclotron, at UBC. Unfortunately, Arthur’s practice was on the verge of bankruptcy. The house therefore, on the one hand was a symbol of world-beating success for Hugo’s business, and on the other, proof of Erickson’s mixture of financial vulnerability and creative exceptionalism. And it was exceptional. Again, no hard limit was set on the budget and no design constraints were evident — an architect’s dream.

First, the design concept called for a three-storey layered structure standing proud of the hillside, rather than the recessed terraces of Eppich I. Second, the structure celebrated Ebco’s now renowned steel fabrication expertise in the massive extruded steel beams retaining the expansive glazed envelope. Third, going beyond Eppich II, the house would serve as memento mori to feature a massive new art collection recently inherited from Egon who had died tragically in an accident a few years before. Milled cedar surfaces would soften the interior spaces but the furnishings would be custom designed in a close collaboration between Arthur and his close companion, interior decorator Francisco Kripacz.

A vaguely Bauhaus/Deco machined finish aesthetic combining glass, stainless steel, and red and yellow leathers was carried through all the furnishings including tables, chairs, lighting fixtures, and even table matts. Each item was crafted in collaboration with engineers and trades specialists in Ebco’s Vancouver fabrication facilities. Light and shade, wall textures and furnishings play against the abstract primary-colour field compositions of Egon’s paintings. Exterior forms and interior spaces descend through the landscape resolving in a series of granite-paved terraces and reflecting pools.

Cornelia Oberlander, the well-known West Coast landscape architect and long-time collaborator on Erickson’s projects, provided a garden setting integrating the formal geometry of the house with a cascading naturalized water garden merging into the enveloping coniferous woodland. The book itself, and especially the stunning visuals, are a celebration of these features. And while different in design and approach, Epoch II joins other recent books exploring Modernist residential architecture on Canada’s west coast, in particular the recent series of four volumes from the UBC School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, including one on the Erickson’s 1964 Smith House.

Bellerby’s narrative and the exceptional illustrations point to a larger dialogue around architectural set pieces such as Eppich II. While accommodating a functional program outlined the by the family (kids wanted bedrooms on the ground floor near the pool), the Eppiches expressly wanted a gesamtkunstwerk or total artwork. This Erickson delivered with great success. While clear from the conversations recorded among the discussants in the text, the gesamtkunstwerk is particularly revealed in the photography. People do not appear in the formal images of the building apart from the construction shots featuring the architects and clients. Any evidence of life is carefully expunged — no kitchen paraphernalia, left newspapers, bowls of fruit, or items of clothing mar the sublimity of the photographs that present this art house. It is a perfect and complete aesthetic expression of itself. Indeed, the Globe and Mail (March 17, 2019) reviewer fretted over the ongoing curation of the house under succeeding generations of ownership!

From the earliest time of his architectural practice, Erickson exhibited a remarkable artistic talent, especially a dramatic sense of sculptural form and space. He credits this to a Zen-inspired creative process that sees the essential spirit of place and time driving the architect’s design response. But it also helped that his building provided a compelling fit with the hard-edge/ high contrast aesthetic of modernist photography, especially as this could be exploited by early post-war black-and-white printing technologies applied to up-scale magazine publication formats.

He played to the camera. Erickson’s work quickly found favour and genuine appreciation among the young and educated. That said, this brand of abstract formalism, found likewise in the work of his spiritual mentors (the Austro-German U.S. emigres (Gropius, Mies, Breuer, Neutra and others), has never found much traction in popular culture.

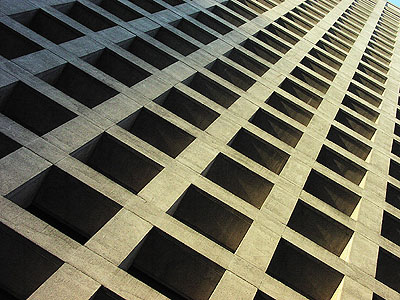

Erickson’s MacMillan Bloedel building, Vancouver (1969). Photo courtesy of Michael Barrick. “A ladder to the sky. Like a tree you almost want to climb it,” writes Barrick

Today the MacMillan Bloedel building, now a diminutive oddity among the soaring mirror- glass towers of the Georgia Street corporate jungle, still powerfully asserts its self-defining monumental scale. Perhaps the intentional subliminal references to the forested tree-scapes of Canada’s west coast (and economic life-blood of its builder) continue to play on the subconscious. But ask a casual man-on-street who walks through its shadow and you are likely to get a not-too-complimentary mumbled reply comparing it to the (oddly enough, Japanese inspired) Matrix of that popular 1999 eponymous dystopian film.

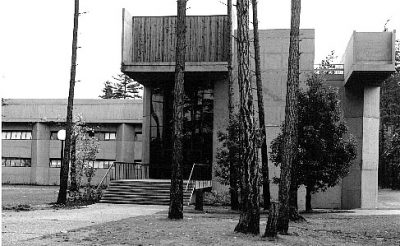

Erickson’s award-winning Lethbridge University was not completed according to his plans or in sympathy with his design intent. The University of Victoria’s brief experience with Erickson as its master-planner was short lived. His recommendation to rationalize the campus plan within a comprehensive design aesthetic was not appreciated and the ponderous expressive concrete forms defining his Biological Sciences building also met with an unsympathetic response.

Eppich II is a bold, if brilliantly crafted, sculptural response to its site. It is certainly photogenic. A Japanese meditative tradition may be behind its conceptual inspiration but the true design legacy goes back to the classical country villas of Britain’s eighteenth-century new-found capitalist Whig aristocracy. Entrepreneurial success celebrated by palatial monuments marks the English countryside. They were intentionally sited to frame views to, and to be seen through, the aesthetically contrived Picturesque landscapes of Capability Brown. New mass production technology in window-pane production and whale-oil candlestick making opened up building envelopes for round-the-clock displays of the elegance and taste — art, furniture collections, sumptuously decorated interiors — of this new class of intellectual and economic change makers. The accompanying rituals required for the daily use of such stages held priority over human comfort and liveability.

This prompts a question seldom asked by architectural reviewers. “But is it liveable?” It seems for the Eppich family that Erickson delivered what both they and Erickson expected and wanted. However there is a hint of something else in the last chapter of Eppich House II, which describes an add-on “studio,” separate from the main house at the end of the small lake that divides the garden from the encroaching woodland. It was designed by Nick Milkovich, Erickson’s project architect of the house, who also provides the commentary.

Under guidance from Hugo Eppich, Milkovich’s studio design evolved from a mere deck to an expansive semi-circular pavilion. Exhibiting authentic West Coast Modern sensibilities, including passive green energy saving technologies, the building almost disappears into its surrounds while at the same time opening up to a view across the pond to create a vista framing the house in its arboreal setting.

Over time the plan gradually morphed to include a den, studio, sitting room, bathroom — in fact the wherewithal, as Hugo admits, for sleepovers and breakfasts. The furniture is casual, familiar, moveable, and functional. It has curtains.

“It’s much more intimate than the big place,” Milkovich notes. From there “you have everything from one spot — the creek, the pond, and the house and the reflections.” Interesting?

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of British Columbia, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on B.C. historic and decorative arts. He currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia, and for Government House, Victoria.

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of British Columbia, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on B.C. historic and decorative arts. He currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia, and for Government House, Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher: The Ormsby Literary Society

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply