#521 The Al Purdy Poets’ Society

March 31st, 2019

Beyond Forgetting: Celebrating 100 Years of Al Purdy

by Howard White and Emma Skagen (editors), with a foreword by Steven Heighton

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018

$22.95 / 9781550178463

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

*

Sheldon Goldfarb reviews an anthology of poems old and new written in tribute to Al Purdy — Ed.

*

A book of poems about a poet. What a notion. But actually poets often write about poets: Milton wrote about Shakespeare, Wordsworth wrote about Milton, Browning wrote (not too flatteringly) about Wordsworth, and most memorably perhaps Auden wrote an elegy to William Butler Yeats: Earth receive an honoured guest/William Yeats is laid to rest, and so on.

A book of poems about a poet. What a notion. But actually poets often write about poets: Milton wrote about Shakespeare, Wordsworth wrote about Milton, Browning wrote (not too flatteringly) about Wordsworth, and most memorably perhaps Auden wrote an elegy to William Butler Yeats: Earth receive an honoured guest/William Yeats is laid to rest, and so on.

A whole book, though: does that happen often? And here brought together in this Harbour Publishing volume is a who’s who of Canadian poetry, from Earle Birney and F.R. Scott to George Bowering and Lorna Crozier. Only Margaret Atwood is missing, but she wrote about him elsewhere. Him being Al Purdy, the last Canadian poet, or the first, or something in between. The people’s poet, the Voice of the Land, the poet even non-poets have heard of — unless they’re in a cafe in Pincher Creek.

The collection gets off with a bang with a poetic recollection by Earle Birney of a visit to Purdy’s A-frame cabin on Roblin Lake at Ameliasburgh, Ontario. It’s not the same Ameliasburgh, Birney’s poem laments. Not the one he read about in Purdy’s poems. Where’s the mill and the mouse? But can the reality ever match the vision? That’s what the poem seems to be saying, but then in a Purdyesque turn at the end (or did Purdy learn it from Birney?), Purdy’s mouse appears (well, a mouse).

Is it all true, then? But professors have taught us that there is no truth, that you can’t go straight from life to art — except, well, maybe you can. A poem by Howard White late in the collection says Eurithe (Purdy’s wife) knows the poetry was formed from life. And Jeanette Lynes, in her contributor’s notes, says what Purdy did is “raise anecdote to art.”

And yet, and yet … Resisting the temptation to see Purdy as presenting or expressing Canadian reality, another contributor, Tom Wayman, says in his poem that though Purdy called it Canada, it was Purdy.

Wayman’s contribution, near the end of the book, seems to be consciously conjuring up Auden’s poem about Yeats, mostly with its title: “In Memory of A.W. Purdy (d. Apr. 2000).” Auden’s poem is called “In Memory of W.B. Yeats (d. Jan. 1939)” and begins, “He disappeared in the dead of winter.” Wayman’s tribute begins, “Death came for him in the spring.” And like Auden, Wayman goes on to discuss the nature of poetry, saying that poets live in words, which are “a damn … constricted … place to live,” and yet those words can endure for centuries. (Just as Auden says that poetry makes nothing happen, and yet time values it, worships it even.)

There is an occasional worshipful note here about Purdy (though there are some deflaters, or at least one, or maybe he is just joking about saying some of Purdy’s poems are nothing but “friendly crap” – but then Purdy himself dismissed some of his own writing, as we learn in the foreword by Steven Heighton and in another poem in the collection about being able to recognize your bad poems).

Purdy was a sort of no-nonsense guy, we learn through this collection, and not averse from a little disrespect even towards Earle Birney. Poets live for competition, the foreword tells us, and they also seem to like to gossip about each other – and they all seem to know each other, perhaps because a lot of them stayed for a while in Purdy’s A-frame house, which eventually became a place to host writers-in-residence.

After a while you begin to think, Is the point of this collection to be a memoir, to teach us about Purdy, or is it to present new (or not-so-new) poems? Are these poems masquerading as memoirs or the other way around?

Some of them do seem to have poetic force, like the Birney piece about reality or Rob Ladouceur’s musings about logs and life or Ian Williams’ hilarious collection of “Ground Rules,” which veers into profundity at the end, like something Purdyesque.

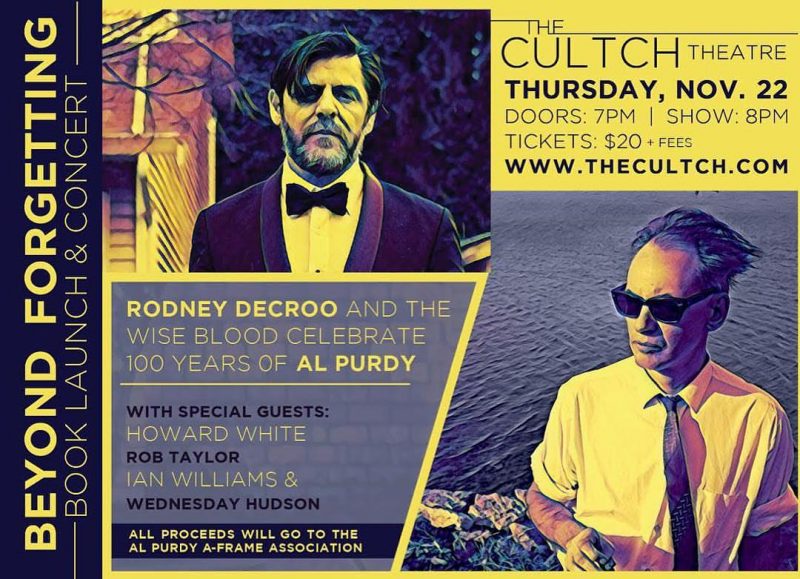

Those would be best, you think, but really the showstopper piece in the whole book is Rodney DeCroo’s account of a poetry reading. Is this poetry? But it’s the best thing in the book, a depiction of the poet as a human being, as an icon to the writer, who can hardly stammer out a word in the presence of his hero, and who is shocked that at one point there’s spittle on Al’s mouth: You’re a literary giant, you can’t have spittle on your mouth.

And then, DeCroo’s piece continues, there’s a kerfuffle: Al is upset to have to wait to do his reading, and by the way he and his wife Eurithe are there mainly to sell some work, make some money. We see the poet as not a god, but, well, like one of us. But then when he finally gets up to read, then there’s magic; our narrator’s hair stands on end; it is as if, okay, of course he’s human, but when he shows us his art, then that redeems it all, and everyone is just spellbound – except, it turns out, his wife, who has fallen asleep. Ah, well.

Anyway, it is brilliant.

And there are meditations on death and the afterlife (the poem right after DeCroo’s, by David Zieroth, most notably, and it is more what you would expect from a poem, exploring abstract notions, but then if Purdy made poetry safe for anecdote, then DeCroo’s piece is a poem too, and did I say how great it is?)

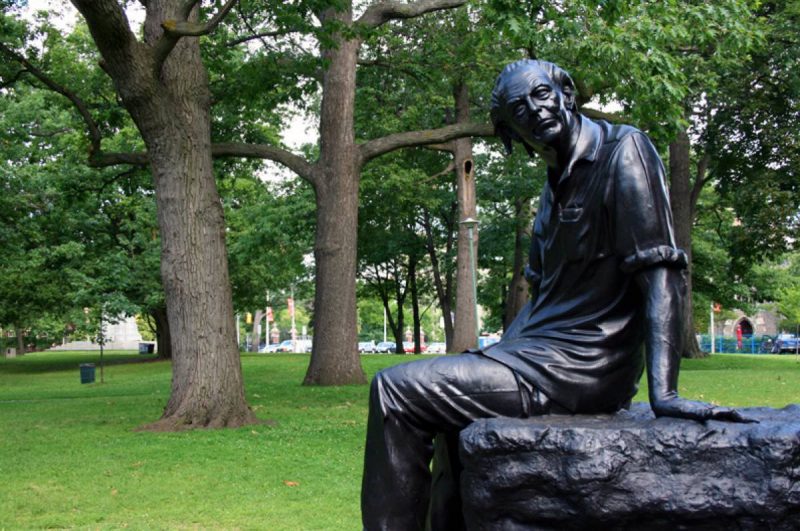

Statue of Purdy at Queen’s Park, Toronto, by Veronica Dam de Nogales, 2008. “No one ever put up a statue to a critic” — Jean Sibelius. Photo by Shaun Merritt

And there are three poems about the Purdy statue in Toronto, one of which quotes his son as saying, yes, I suppose that’s him; I don’t remember the beatific smile, though. And you can look this image up if you like: there are lots of photos of the statue online. Is it a beatific smile? It actually looks more like a frown. Or perhaps it depends on the angle of your view, which of course is everything in poetry.

I scurried online a lot while reading this book. I’d better read some of the poems these poets are alluding to, I thought, and I found some wonderful stuff by Purdy: “Trees at the Arctic Circle,” with its surprising shift at the end, or Gord Downie performing an acting out of “At the Quinte Hotel.” Or Gordon Pinsent making you cry with the account of mother and son in his reading of Purdy’s “On Being Human.”

And there’s Margaret Atwood online too, talking about the time she dumped a bottle of beer over Purdy’s head because he called her a very bad name. They became friends later, though. (The very bad name was “academic.”)

And then back to the book, in the notes, the hilarious anecdote about the poet who quoted three lines from Purdy in a poem of his own, leading Purdy to comment that it was a pretty good poem: “At least it has three good lines.”

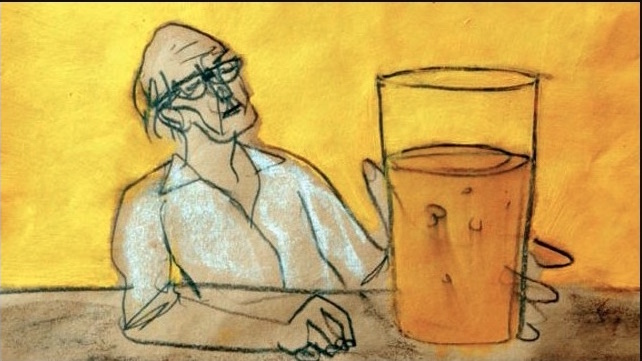

Bruce Cockburn sings “Three Al Purdys.” “I’ll give you three Al Purdys for a twenty-dollar bill.”

And there’s Bruce Cockburn here with what is really a song; it even rhymes; it has a chorus: all about selling three Al Purdys: “The winds of fate blow you where they will/I’ll give you three Al Purdys for a twenty dollar bill.”

And Al becomes a horse or a cat or inspires a poem about a sad butterfly walking on the ground. And his wife was either his muse or the brake on his runaway imagination. And he threw beer bottles out of windows into the snow, which appeared in the spring like crocuses.

He had a mind leaping from place to place, Patrick Lane says in his contribution, and “found love at the end of … complaint.” “Poems go round and round,” Lane adds (“this one too”), “never quite getting there.” Because they are constricted things? Because, as Candace Fertile puts it in her meditation on the Quinte Hotel, poetry is powerless, which is what Purdy’s Quinte Hotel says itself (maybe): it can’t buy you a beer. But it can buy a place in your brain, says a student in Fertile’s poem, and maybe it can.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017). He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember, was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. Originally from Montreal, he has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and two degrees from the University of British Columbia: a PhD in English and a master’s degree in archival studies.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply