#441 Poems of journeys and change

December 06th, 2018

The Small Way

by Onjana Yawnghwe

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2018

$18.00 / 9781987915778

Reviewed by Renée Saklikar

*

We were speaking then of necessary journeys, of the way the reading of a book might become a crossing-over into other people’s territory, for instance into those migrations that are within the smallest interiors, such as the beginning and then the end of a marriage, or of any relationship, real or imagined, and into a journey that brings us to memory, a closing-shut-open door that leads to explorations of the nature of loss.

We were speaking then of necessary journeys, of the way the reading of a book might become a crossing-over into other people’s territory, for instance into those migrations that are within the smallest interiors, such as the beginning and then the end of a marriage, or of any relationship, real or imagined, and into a journey that brings us to memory, a closing-shut-open door that leads to explorations of the nature of loss.

A new and specific kind of loss is the subject of this haunting book of poem-vignettes, The Small Way, by a Vancouver writer who is also a nurse: Onjana Yawnghwe.

As a long poem writer, I tend to read all poetry as though each poem encountered is part of some greater design, and with The Small Way, concerning Yawnghwe’s marriage to a man who eventually becomes a woman, each poem appears as part of a series of inter-connected elegies that weave back and forth into a beginning: love, infatuation; middle: marriage and the realization of a profound change; and end: perhaps pre-ordained and yes, endlessly sad, and also liberating.

Once, when travelling by train in a far away country, I overheard two passengers deep in conversation. They were seated side by side: the man, tall, broad shouldered, with an angular jaw and auburn hair; his companion, her dark shiny hair in a large top bun, rather stout, or so she seemed to me.

I sat ahead of them, with my back to their voices, so that, in order to better overhear them, which I very much wanted to continue doing, I would get up to visit the train’s toilet, being sure to turn into the compartment bearing the graphic depicting a stylized female, concerned lest I find myself in the men’s, where a young sports team, one by one, entered for lightning quick moments and then trailed out — and I’d smile, engrossed by my desire to return to the man and the woman, to well, yes, “check them out,” and then settle back into my seat ahead of them, or behind, depending on which direction on the train I might be heading.

I sat ahead of them, with my back to their voices, so that, in order to better overhear them, which I very much wanted to continue doing, I would get up to visit the train’s toilet, being sure to turn into the compartment bearing the graphic depicting a stylized female, concerned lest I find myself in the men’s, where a young sports team, one by one, entered for lightning quick moments and then trailed out — and I’d smile, engrossed by my desire to return to the man and the woman, to well, yes, “check them out,” and then settle back into my seat ahead of them, or behind, depending on which direction on the train I might be heading.

The man and the woman spoke about childhood memories and they, too, commented on the sports team (the parade of young men were rugby players), and about memories of televised sporting events, chiefly the Olympics, and both almost at the same time said, “Oh remember Bruce/ Caitlyn Jenner,” and the man then said, “well my parents had the T.V. on all the time, when he/they won the Decathlon and then after — ”

And at that pause, the tall man rose, stretched, took out his iPad from the overhead bin, sat down again, click, click, click, and the woman and he spoke at length about the journey, the crossing-over of Bruce to Caitlyn, with much discussion of the reality TV show, Keeping Up with the Kardashians.

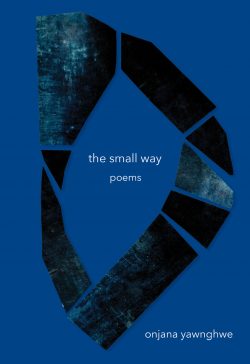

And this memory of a train conversation of strangers, and of my unease at entering an interior place designated as Male and also occupied by men, held itself fixed in my mind as I opened the pages of Yawnghwe’s book, with its dark blue cover and photograph of a darkly green wood, barely any light — a reference, surely, to Dante — the graphic, splintered into fragments, arranged in an oval circle in the shape, perhaps, of a symbol indicating both male and female, and inside, starkly white pages.

And this memory of a train conversation of strangers, and of my unease at entering an interior place designated as Male and also occupied by men, held itself fixed in my mind as I opened the pages of Yawnghwe’s book, with its dark blue cover and photograph of a darkly green wood, barely any light — a reference, surely, to Dante — the graphic, splintered into fragments, arranged in an oval circle in the shape, perhaps, of a symbol indicating both male and female, and inside, starkly white pages.

Each poem-vignette in The Small Way reads to my eye, and sounds to my ear, as a bit of story, linked by this journey of beginning, middle, end, and crossing-over. And each of these poem-vignettes, imbued with the complexities of that transition, emanates a delicate courage: here is a poet who is prepared not only to speak about her pain, but to endeavour to speak for another.

Among the artistic demands a writer might encounter in trying to write about trauma, this attempt to speak and represent another always looms as terrifying, tricky, and ultimately admirable.

Yawnghwe constructs her journey poem with her poet’s gaze fixed on this Other, her husband, who, as a woman, abandons both the male gender and their marriage. The Small Way begins with a Prologue, ends with an Epilogue, and the poem-vignettes are placed in sequences that perhaps are designed to be read as a novel.

Each poem-vignette might be read as “Scenes from a Marriage” and often, a poem’s first part, blocked in little columnar stanzas, then gives way to a second part of Kaon-like observations with a kind of psychic space between the parts. The poem “Skin, Memory,” employs the extended metaphor of astrophysics:

How we unzipped ourselves

and collided in the most joyful way.

We watch each other

from either side of the pole now,

your demeanour equatorial,

neither north or south.

The Big Bang happened, there’s that.

Worlds pressed and formed

from anguish and wanting.

Explosions and compressions of asteroid

and hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon

are uninhabitable for me.

I limp in and out of orbit around you

My gait like an aged butler who topples

From too much polishing of silver.

The use of this extended metaphor of astrophysics occurs throughout Yawnghwe’s book, with words such as planet, moon, sun, stars, gravity, universe, black holes, subatomic, space travel, and voyage; and each occurrence serves to deepen and amplify the sensation of both travel and of otherness, of two objects in orbit whose trajectory is disrupted by a cataclysmic change, which the poet calls “The Big Bang.”

The use of this extended metaphor of astrophysics occurs throughout Yawnghwe’s book, with words such as planet, moon, sun, stars, gravity, universe, black holes, subatomic, space travel, and voyage; and each occurrence serves to deepen and amplify the sensation of both travel and of otherness, of two objects in orbit whose trajectory is disrupted by a cataclysmic change, which the poet calls “The Big Bang.”

In several sequences of poems, Yawnghwe’s husband’s decision to become the woman they’ve always meant to be, and then their further trans-journey as a queer-trans woman falling in love with another woman, while still living with the poet, is described in vignettes that risk missteps, where the “telling” seems perhaps too “on the nose,” such as in the poem “Of Pure and Informed Chances:”

You seem so happy it hurts.

You two drink from each other’s mouths

never full and constantly wanting.

Her long blond hair curls over you

as you wrap your long arms around hers…

Repetition of such memes helps hold the book in narrative place, although at times the poems that are, in effect, laments for the man who once was, as seen by his former wife, perhaps veer into the arena of self-confession and thus begin to leach energy from the page. In “Of Pure and Informed Chances,” representative of such poems, we read poetic content expressed in irregular boxed stanzas with indeterminate pronouns that weaken the brave loveliness of the journey: “I have drunk deeply from the river,/ It washes over me in currents./ The heart always declares itself.”

Repetition of such memes helps hold the book in narrative place, although at times the poems that are, in effect, laments for the man who once was, as seen by his former wife, perhaps veer into the arena of self-confession and thus begin to leach energy from the page. In “Of Pure and Informed Chances,” representative of such poems, we read poetic content expressed in irregular boxed stanzas with indeterminate pronouns that weaken the brave loveliness of the journey: “I have drunk deeply from the river,/ It washes over me in currents./ The heart always declares itself.”

Perhaps, however, to make such criticisms falls prey to a practice of close reading that misses the point: this is the courageous witness of a most intimate journey: one of searing pain for the narrator and of liberation, and of becoming, for The Other.

In the middle of the book, we are given a revelation of the book’s title, The Small Way, in a three-part poem with the same name, itself eponymous with a painting by Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser, in which the poet speaks of a chapbook she and her then-husband made, and thus the Prologue, “Chapbook (2004),” is made more clear in a way that leads us back to the beginning of the book and then forward into the remaining poem-vignettes and the ultimate disintegration of the evoked relationship:

The Small Way

2.

We create a chapbook together,

Your poems and mine, back to back.

Dos-á-dos. Back to front. Left and right.

For hours we hand-stitch the pages

together with waxed thread.

We call it “The Small Way.”

The index finger separates one page from the other,

but the time between poems is immense.

All around the world,

Windows open.

Everything about this section of this poem entices and represents the best of Yawnghwe’s book: the way the subject matter is delicately threaded into layers, the way the line-breaks encourage the eye back and forth so that content and form create a satisfying whole, the disruption of space between the first eight lines and the remaining two, as if the first part of the poem might have been a sonnet; and at the place traditionally reserved for the “turn,” we encounter absence, that beautiful final couplet, leading to contemplation as if it, too, was once part of this larger and more elaborate structure; and yet it floats beautifully with its gesture to that Austrian saying, “I keep passing the open windows,” where one finds oneself on “the way:” surviving and possibly healing despite tragedy and loss —

Everything about this section of this poem entices and represents the best of Yawnghwe’s book: the way the subject matter is delicately threaded into layers, the way the line-breaks encourage the eye back and forth so that content and form create a satisfying whole, the disruption of space between the first eight lines and the remaining two, as if the first part of the poem might have been a sonnet; and at the place traditionally reserved for the “turn,” we encounter absence, that beautiful final couplet, leading to contemplation as if it, too, was once part of this larger and more elaborate structure; and yet it floats beautifully with its gesture to that Austrian saying, “I keep passing the open windows,” where one finds oneself on “the way:” surviving and possibly healing despite tragedy and loss —

*

References

Various internet journeys: Bruce/Caitlyn Jenner: google and Wikipedia and a few hours (nay, about twenty minutes) watching Kim Kardashian’s show and then more time, on google, trying to keep straight details about the Jenner-Kardashian saga.

Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook and The Grandmothers and, from memory, bits from an essay she prepared that once appeared online upon her acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize for Literature. And from memory, real/imagined, of her voice from a long-ago CBC Ideas program.

Email Correspondence (from some time ago): with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, about ideas in Can the SubAltern Speak; and with Dr. Angela Failler, Associate Professor of Women’s & Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Culture and Public Memory at the University of Winnipeg.

On the Bus, in Paris: with Sarah Ahmed, about her manuscript for what would become the essay, A Willfulness Archive, and a conversation about a talk Ms. Ahmed gave at an ACS conference, 2012 (http://www.crossroads2012.org/)

*

Renée Saklikar, 2017. Photo by Sandra Vander Schaaf

Renée Sarojini Saklikar recently completed her term as the first Poet Laureate for the City of Surrey, British Columbia. Her latest book is a B.C. bestseller: Listening to the Bees (Nightwood Editions, 2018). Renée’s first book, children of air india, (Nightwood Editions, 2013) won the 2014 Canadian Authors Association Award for poetry. Renée co-edited The Revolving City: 51 Poems and the Stories Behind Them (Anvil Press/SFU Public Square, 2015), a City of Vancouver book award finalist. Renée’s chapbook, After the Battle of Kingsway, the bees, (above/ground press, 2016), was a finalist for the 2017 bpNichol award. Her poetry has been made into musical and visual installations, including the opera, air india [redacted]. Renée was called to the BC Bar as a Barrister and Solicitor, served as a director for youth employment programs in the BC public service, and now teaches law and ethics for Simon Fraser University in addition to teaching creative writing at both SFU and Vancouver Community College. She curates the popular poetry reading series, Lunch Poems at SFU and serves on the boards of Event magazine and The Capilano Review and is a director for the board of the Surrey International Writers Conference. Renée is currently working on an epic-length sci-fic poem that appears in journals, anthologies, and chapbooks.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply