#440 A Settler-Witsuwit’en example

December 05th, 2018

Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973

by Tyler McCreary

Smithers: Creekstone Press, 2018

$24.95 / 9781928195047

Reviewed by Keith D. Smith

*

In Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973, historical geographer Tyler McCreary, who grew up at Smithers in the Bulkley Valley, shows that relations between settlers and Witsuwit’en people were not always characterized by distance or acrimony. McCreary, according to reviewer Keith Smith, provides “numerous examples where the Witsuwit’en and the settler community in Smithers were brought together at a personal level, for example through sports, paid work, and schooling.” — Ed.

*

Long before the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015, many observers struggled to figure out how we got to a place in Canada where an investigation like that conducted by the TRC was necessary, let alone what “reconciliation” might mean to future relations between Indigenous peoples and those of us of settler descent.

Long before the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015, many observers struggled to figure out how we got to a place in Canada where an investigation like that conducted by the TRC was necessary, let alone what “reconciliation” might mean to future relations between Indigenous peoples and those of us of settler descent.

A similar impetus to the conditions that drove Canada to investigate past injustices has resulted in a growing body of literature exploring the history of Indigenous-settler relations — writing that seeks to reverse the erasure of Indigenous peoples in the stories Canadians tell each other about our collective past, and which considers how the lessons we learn might be helpful in providing a path to a much more equitable future. Shared Histories: Witsuwit’en-Settler Relations in Smithers, British Columbia, 1913-1973, by historical geographer Tyler McCreary, is a valuable, nuanced, and richly local addition to this corpus of study.

McCreary is open about his authorial position as a descendant of settlers. As someone who grew up in Smithers, he is uniquely positioned to write the stories included here. An ambitious research project from the outset, this book will appeal to academic and popular audiences alike.

Wos Tyee Lake David Francis (far left) and his brother Jean Baptiste, far right, with their families in the early 1920s on their properties near Smithers. Baptiste’s property is now a reserve and David Francis’s land is still owned by the family. Telkwa Museum photo

As the title implies, McCreary’s goal is to explore the creation of Smithers, a small town in the Bulkley Valley in west-central British Columbia, as an “inclusive community where Witsuwit’en and settlers both participate in determining their collective future” (p. 209). Shared Histories, then, is a local history and an important contribution to that genre, but it also has national and even global implications. This book demonstrates an inclusive way of writing history and implicitly encourages us to decolonize ourselves and reconsider how we think about our shared future.

Margaret and Minnie Joseph on their father’s trapline on McDonell Lake, 1940s. Courtesy of George Joseph

McCreary breaks his study into ten relatively short and easily digestible thematic chapters. In each, he combines archival research, academic and popular histories, newspaper sources, and oral interviews, which together underpin an ambitious, thoughtfully conceived, compellingly argued, and beautifully presented book. Laced with photographs collected from archival sources and personal collections, McCreary includes portions of interviews in separate text boxes throughout the book. Readers will also find helpful historical and modern maps and plans, a glossary, and guides to Witsuwit’en place names and pronunciation.

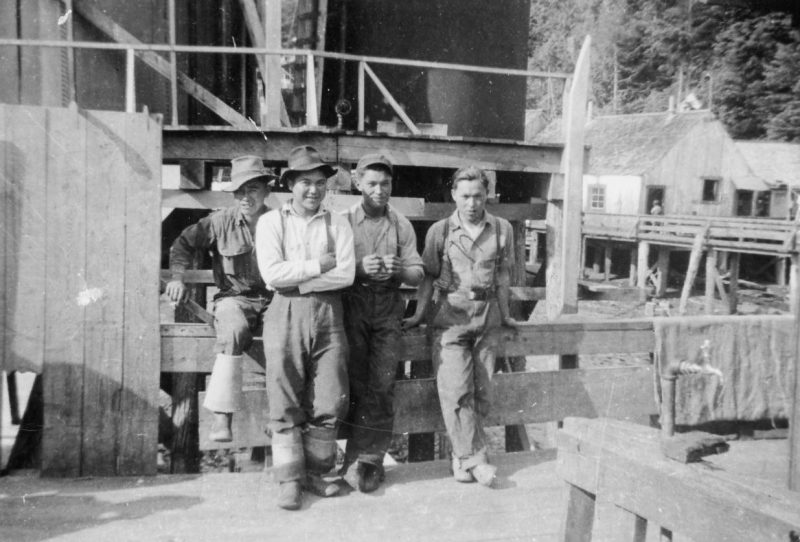

L-R: Frank, Alex, Louie, and John Joseph at the cannery in Port Essington at the mouth of the Skeena River, circa 1950. Many Witsuwit’en men fished and logged seasonally. Courtesy of George Joseph

While Shared Histories illustrates Witsuwit’en and settler communities working together at times in the interest of their collective well-being, McCreary does not shy away from demonstrating the discrimination that the Witsuwit’en faced from local settlers and more distant governments and agencies. He casts a wide net to explore sub-standard treatment encountered in access to health care, education, municipal services, as well as in wage work and other economic activity.

L-R: Kathleen Tom and Violet Bazil (Gellenbeck) (Kilisït), who attended school in Smithers in the 1950s. Courtesy of George Joseph

McCreary details how the Witsuwit’en were indispensable to the early capitalist economy, particularly in resource extraction industries; and how, after reshaping their own economic structures, they were systematically excluded from these economic opportunities. They also witnessed the growth of industrial capitalism and the attendant construction of infrastructure, such as road and railway building and hydroelectric development, which opened up long-established Witsuwit’en resource sites to non-Indigenous hunters and fishers.

At the same time, structural changes and a skewed regulatory regime reduced Witsuwit’en flexibility to shift between subsistence activities and wage work, just as growing levels of state surveillance operated in concert with increased governmental intervention and restriction into the lives of Witsuwit’en families. McCreary also recognizes the importance of what scholars have recently defined as intersectional analysis.[1] He effectively demonstrates settler society’s penchant for presenting Indigenous women as biologically inclined toward wanton sexuality, which also required enhanced state discipline, surveillance, and restrictions on freedom of movement. This, he points out, served to further normalize violence against Indigenous women and reduce their agency as independent actors.

McCreary outlines sex discrimination in the Indian Act and its effects on women who married non-Witsuwit’en men, and he provides an important explication of the normalization and imposition of middle-class settler values on Indigenous women and their families. While he details Canada’s efforts in support of industrial capital at the expense of the Witsuwit’en community, he could have been a little more attentive to intersectionality as it is connected to issues of class.

Louie Joseph and his son George at Indiantown, a Witsuwit’en settlement on the edge of Smithers created soon after the town’s establishment in 1913. Courtesy of George Joseph

McCreary also seeks to overturn stereotypes that continue to find their way into settler discourse about Indigenous peoples. In the 21st century, such explications should not be necessary, but Shared Histories illustrates the Witsuwit’en as comprised of generous, hard-working, law-abiding people facing their changing situations across time in intelligent and open-hearted ways. While the Witsuwit’en struggled in their relationships with their settler neighbours and in their efforts to walk in two worlds, McCreary demonstrates that “respecting settler law did not require abandoning their rights or respect for Witsuwit’en law” (p. 120). As was the case with other Indigenous communities, attempts to erase the Witsuwit’en by policy, legislation, and simple acts of racism were ultimately unsuccessful.

Shared Histories is not an overly romantic account. It does, however, make abundantly clear that — despite the array of structures and understandings mitigating against cultural resilience and despite the obvious imbalance in relations of power — the Witsuwit’en have demonstrated a remarkable degree of resilience.

Through the maintenance of kinship networks, the Witsuwit’en effectively resisted or at least reduced the impact of the colonial onslaught to maintain and sustain cultural identity and community cohesion, even though at times “kin networks were being overwhelmed as large numbers of people struggled to overcome the legacies of oppressive schooling, criminalization, work-place discrimination, and enduring poverty” (p. 184). McCreary illustrates Witsuwit’en agency in their ability, at times, to moderate the worst of child apprehension policies and the most discriminatory and ethnocentric aspects of welfare and health regimes, gender discrimination, and unfair labour practices.

Despite the often-acrimonious relations between Indigenous peoples and settler society, McCreary provides numerous examples where the Witsuwit’en and the settler community in Smithers were brought together at a personal level, for example through sports, paid work, and schooling. It is at this personal level that McCreary believes historical wounds can be healed. This is perhaps a lesson that can be helpful well beyond the context of central and northern British Columbia.

Shared Histories has a lot going for it. McCreary has gone to some effort to make this a collaborative project and to include a variety of voices in his narrative. But no work is perfect. Some academic readers might expect a clearer indication of the author’s methodology. He identifies an advisory committee in his acknowledgements, but nowhere provides anything definitive on how the interviews were structured or his criteria for interview selection. I also felt that short biographies of the most significant players in the narrative might have been helpful to those unfamiliar with the context.

And while McCreary brings together a diverse array of sources, he also seems to have missed major collections of potentially productive records. The Department of Indian Affairs Annual Reports might have provided an additional gateway into the thinking of Canadian authorities and local officials.

Equally, McCreary cites newspaper accounts of police activity, but does not seem to have consulted the records of policing bodies themselves. And while he writes about the Native Brotherhood in several places, he seems to have missed the organization’s official publication, The Native Voice, which is readily available digitally for at least some of the period under discussion.

These quibbles, which might be overly technical for many readers, do not alter the fact that this book deserves a wide readership.

Shared Histories belongs on every British Columbian’s bookshelf as a resource for those interested in the roots of Indigenous-settler relations, as an example for future authors, and as a template of how we might work together toward a more equitable future.

*

Keith Smith is a professor of Indigenous/ Xwulmuxw Studies and History at Vancouver Island University. His research interests focus on the relationships between Indigenous peoples and settler societies and his published works include Liberalism, Surveillance, and Resistance: Indigenous Communities in Western Canada, 1877-1927 (Athabasca University Press, 2009), Strange Visitors: Documents in Documents in Indigenous-Settler Relations in Canada from 1876 (University of Toronto Press, 2014), and most recently Talking Back to the Indian Act: Critical Readings in Settler Colonial Histories (University of Toronto Press, 2018), co-edited with Mary-Ellen Kelm. Keith lives in Victoria on the traditional territory of the Lekwungen and Esquimalt peoples with his wife Leanne, son Clayton, two dogs, and a very patient cat. He fills his summers with road trips, camping, and trying to avoid home improvement projects.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] Intersectional analysis is an “analytical tool,” according to Wikipedia, “for understanding and responding to the ways gender identity intersects with and is constituted by other social factors such as race, age, ethnicity and sexual orientation.” Intersectionality “attempts to identify how interlocking systems of power impact those who are most marginalized in society.” — Ed.

Leave a Reply