#412 Vancouver jazz scene

November 02nd, 2018

Live at the Cellar: Vancouver’s Iconic Jazz Cub and the Canadian Co-operative Jazz Scene in the 1950s and ‘60s

by Marian Jago, foreword by Don Thompson

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018

$29.95 / 9780774837699

Reviewed by Brian Fraser

*

Good books on jazz are filled with intriguing stories about the relationships that generate such an energizing art form. This book is that, and more. The more is a carefully considered framework for making sense of the social dynamics that create a jazz scene. Put the stories into the framework and you’ve got a must-read book.

Good books on jazz are filled with intriguing stories about the relationships that generate such an energizing art form. This book is that, and more. The more is a carefully considered framework for making sense of the social dynamics that create a jazz scene. Put the stories into the framework and you’ve got a must-read book.

Make sure you don’t skip the opening chapter. It’s a bit academic, but in the best sense of that word. Drawing on the work of musicologist Christopher Small and urbanist Alan Blum, Jago poses a description of how her subjects made a scene at the Cellar:

… a scene functions as a lifestyle rather than a pastime — music making is then a socio-cultural experience predicated upon the entwined practices of listening and performing, of seeing and being seen, and of a sociability imposed by the constraints of space and place. Scenes, however, are not necessarily places of universal positivity or inclusion, and the politics of economic class and gender expectations may affect the musical activities of the scene and the behavioural codes that govern it (p. 21).

To put flesh on the theory and let real life refine it, Marian Jago has been doing interviews, digging through archives, listening to recordings, and testing out paradigms for understanding urban places and spaces for almost twenty years. She has drawn together her mature reflections on all this work into this book with all the grace, flow, and surprise of a great jazz suite.

As I read her framework, she pays attention to the interactions of people, purpose, place, and process. Who are so passionate about jazz that they are willing to take entrepreneurial risks to create and sustain places to play and hone their chops in company with appreciative audiences? In the late 50s and the early 60s, they were an intriguing mix of young musicians who felt shut out of the better-paying, more traditional gigs “downtown,” but who were determined to follow their passions and create a space where the newer forms of jazz could be learned and enjoyed.

Ken Hole was one of the enterprising young jazz musicians who dreamed up the idea of creating a cooperative, The Cellar, to nurture a new jazz scene in Vancouver and connect it with the innovations happening elsewhere. Here’s what he saw happening:

… soon we didn’t have enough room there for everybody on a Saturday night or a Friday night…. I mean it was camaraderie, and everybody talked shop, and everybody was learning from these musicians coming up from California. They’d learn a new method of playing jazz, and some phrasing that we’d never heard before, and the next thing you’d know, the local guys would be doing it (p. 88).

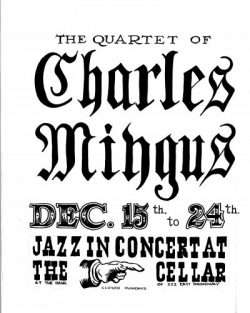

The stories that Jago has woven together provide fascinating details of this process. Among the most intriguing are various versions of bassist and composer Charles Mingus taking a bathroom plunger to a group of BC Lions football players who would rather talk than listen (pp. 172-182).

The Cellar was a basement in a building at 222 East Broadway, between Main and Kingsway. The entrance was off a small parking lot at the back. It was a “private club” to get around Vancouver’s liquor laws, permit process, and insurance requirements. In keeping with the desire to support a broad range of the arts, striking murals were painted on the stairway and one interior wall. Plays and poetry readings happened in the space, along with the jazz.

Advance poster for Charlie Mingus concerts at the Cellar, 1960, designed by Harry Webb. Adrienne Brown Collection

And it had a special feel. Lyvia Brooks, whose family had the shirt shop upstairs, described the special feel of the club this way: “People were definitely there to enjoy the music. …the Cellar was, again, like a sanctuary. There was peace and calm, and you were accepted no matter who you were, and you sat and enjoyed the music, and as long as you respected that you were fine there” (p. 74).

The BC Lions’ players accosted by Mingus, then, were clearly an exception.

Jago takes care to remark on those who are left out of the scene, especially women and people of colour. This is, by and large, a scene of white males. Hopefully, those making today’s jazz scene will find ways of being more inclusive.

Running a co-op is never easy, no matter how noble the purpose. In the late 1950s, a serious division arose between those simply wanting to preserve a place to play and those wanting to expand the business to increase popularity and profitability, resulting in the resignations of some of the founding members. Jago tells this story with fairness to both sides and also ties it in with the challenges of running other jazz locations in Vancouver and across Canada. All in all, the book offers an astute analysis of the ups and downs of operating a jazz club all across the country.

In the August 2018 issue of DownBeat, contemporary jazz pianist Vijay Iyer, who is designing a new jazz program at Harvard, says that jazz is more a community than a style of music. Jago gets that. And her history of the community that was jazz in Vancouver in the late 50s and early 60s is a delightful account of this reality.

*

Brian Fraser is minister with Brentwood Presbyterian Church and a consultant and leadership coach with Jazzthink, a company that uses the wit, wisdom, and workings of jazz to provoke flourishing communities. Brian completed his Ph.D. in history with Ramsay Cook at York University in 1982 and came to B.C. in 1985 to be dean of St. Andrew’s Hall, the Presbyterian college at UBC, and to teach history at Vancouver School of Theology. He has published three academic books, along with academic and popular articles on a wide range of topics related to communal wellbeing. The focus of his historical work is leadership and organizational development in faith-based non-profits. He resides in North Vancouver with his wife, Jill Alexander. Brian also moderates conversations in the SFU Philosophers’ Cafe program.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

L-R: Al Neil, Bob Frogge, Freddie Schreiber, Bill Boyle, and John Dawe at the Cellar, circa 1958. Courtesy Jim Carney

Poster for the Montgomery Brothers Quartet, the Cellar, 1961. Designed by Harry Webb. Courtesy Adrienne Brown

Leave a Reply