Inter-generational trauma

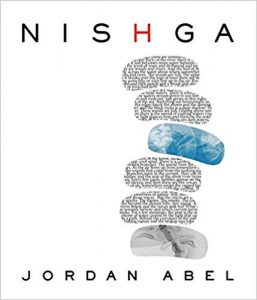

Jordan Abel's new book is a painful confrontation of the devastation his ancestors faced, and that he would eventually too, due to Canada's residential school system.

February 13th, 2020

Jordan Abel recently completed a PhD at SFU and now teaches at the University of Alberta.

“Nishga is not a poem, essay or a letter,” writes reviewer Latash Maurice Nahanee. “It is a documentation of one man’s life journey and it is the journey of thousands of young Indigenous people.”

Review by Latash Maurice Nahanee

Jordan Abel is an Indigenous scholar and poet. His new book, Nishga (McClelland & Stewart $32.95) tells of his life journey and the problematic story of the impact of colonization.

As an Indigenous person I share his position of sometimes having to answer for the atrocious impacts of the federal legislation called the Indian Act. When asked, “What kind of Indian are you?” It is difficult not to become angered. My dad would answer, “I’m a darn good Indian.”

Like most of us, Abel, came into an environment not of his own choosing. If he had a choice, it would have made a great difference. But then, we may not be hearing his voice; that of an urban Aboriginal person who is affected by inter-generational trauma.

Like most of us, Abel, came into an environment not of his own choosing. If he had a choice, it would have made a great difference. But then, we may not be hearing his voice; that of an urban Aboriginal person who is affected by inter-generational trauma.

The first Prime Minister, John A. MacDonald was also the first Minister of Indian Affairs. When Canada became a country in 1867, a wave of destruction was set in motion.

Jordon Abel’s story begins with the founding of Canada and he quotes Sir John A. MacDonald: “It has been strongly pressed on myself as head of the Department, that Indian children be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of white men.”

This was the beginning of the Indian Residential school system. Abel points out that these Indian residential schools offered much more than a liberal education. They were run by men and women who sexually abused children, used corporal punishment as a measure to curb the speaking of their Indigenous languages, and allowed medical starvation experimentation on inmates.

Sir John A. Macdonald (1815-1891). National Archives of Canada.

Abel’s grandparents met at Coqualeetza Residential School in Sardis. They were Nisga’a from the Nass Valley of Northwestern B.C. Their formative years were spent without the love of their parents and extended families. Lacking the nurturing of a loving family, his grandparents began a dysfunctional life. The trauma of their life together was passed onto their son Lawrence Wilson.

Many Nisga’a attended Indian residential schools far from their homeland. And many returned to their extended families where they began to relearn their culture and language. Leaders such as James Gosnell, Frank Calder and Rod Robinson, upon returning to the Nass, became part of a generation of leaders who would win the first modern treaty in BC. They too attended the Coqualeetza institution.

However, Abel’s grandparents did not return to the Nisga’a homeland. They moved to Vancouver. This change of trajectory would prove to be a devastating turning point for the family.

Abel’s parents split apart soon after he was born. This resulted in the family moving to Toronto. He was raised by a single settler mother. The result was that he was cut off from his Indigenous roots.

Coqualeetza Residential School in Sardis, near Chilliwack, B.C.

Nishga is not a poem, essay or a letter. It is a documentation of one man’s life journey and it is the journey of thousands of young Indigenous people. Over 150,000 children were forcibly removed from their homes by RCMP and clergy and placed in institutions called Indian Residential Schools starting in 1867. The federal government began a process of closing these institutions in 1958 and replaced them with Indian day schools. I attended a day school starting in 1962 and left in 1969 to go to St. Thomas Aquinas High School. In my experience, I was forbidden to speak my language at school and at home. I was not taught First Nations history or culture. My parents did not teach me about my language or culture. But I had uncles and aunts who were cultural elders and mentors.

I can imagine what it was like for Jordan Abel being raised so far from his homeland by his mother. Her experience with Indigenous people and culture was limited and negative. In urban centres like Toronto, when you look different from other children the questions arise about what your ethnicity is! When you don’t know, then it is difficult to answer. His schools years were marred by racism.

Jordon Abel at the time of this writing is completing his doctoral degree. He is in the top intellectual percentile of the Canadian population. He is an anomaly in many senses of the word. He identifies as Nisga’a because his father is Nisga’a. Since the Nisga’a are famous for their landmark treaty victory he unwittingly becomes a target of many inquiries.

The Nisga’a are among the few celebrity First Nations in Canada. People are curious about the Nisga’a. Starting in the 1980’s until the signing of the treaty the Nisga’a became big news. I was a journalist during this time and I wrote about their struggle to get a treaty. On TV, the Nisga’a were big news. Closer to home, I married a Nisga’a; her name is Delgamha. Her father is the hereditary chief, Simooegit Hymas. He was one of the main negotiators of the treaty. So I learned first hand about the Nisga’a people and their amazing culture.

MLA Frank Calder is known for his role in the Nisga’a Tribal Council’s Supreme Court case against B.C. which demonstrated that Aboriginal title (i.e., ownership) to traditional lands exists in modern Canadian law.

One troubling aspect of Jordon Abel’s Nishga is the lack of research on available Indigenous sources. In 1993, a book titled Nisga’a was published by Douglas & MacIntyre. It was done with the assistance of hereditary leaders. It is the compelling story of a people determined to live in a distinct society based on the teachings of their ancestors. There is also the Nisga’a court case known as Calder v. British Columbia (Attorney-General) which is available to the public. And there are dozens of news articles, TV documentaries and news reports. I did a Google search and found many interesting facts about the Nisga’a. In short, there are scores of sources for written documents by and about the Nisga’a. And yet we find none of them referenced in Jordan’s book. He does quote Sir John A. MacDonald and anthropologists such as Marius Barbeau (1883-1969). These are not reliable sources.

The pain and suffering of thousands of displaced Canadian Aboriginal people is illuminated in Nishga. Much has been invested in getting rid of the Indian problem in Canada. More funds need to redirected to working collaboratively with Indigenous people to provide the best possible life for everyone. This is not “the Indian problem,” it is everyone’s problem. Canada is a land that is rich in resources. There is wealth that can be more equitably distributed for the benefit of all Canadians.

Injustice for one, is injustice for all.

978-0771007903

*

Latash Maurice Nahanee is the Indigenous Editor for BC BookWorld. He is a member of the Squamish First Nation.

Latash Maurice Nahanee is the Indigenous Editor for BC BookWorld. He is a member of the Squamish First Nation.

Leave a Reply