#351 Essays from the north

August 24th, 2018

Where it Hurts: Essays

by Sarah de Leeuw

Edmonton: NeWest Press, 2017

$19.95 / 9781926455846

Reviewed by Heidi Greco

*

Heidi Greco reviews Sarah de Leeuw’s Where it Hurts: Essays, a collection that has been much-praised and shortlisted for national and regional non-fiction prizes. “These aren’t the essays your high school teacher sought,” writes Greco. “These twist and turn, unfolding on their own trails, leading the reader into unexpected and often dark places. — Ed.

*

As our high school teachers cajoled us, the word “essay” comes to us from the French word, essayer, meaning “to try.” While school essays may well have been more trial than try, the essays in this book demonstrate how far the form can be taken.

As our high school teachers cajoled us, the word “essay” comes to us from the French word, essayer, meaning “to try.” While school essays may well have been more trial than try, the essays in this book demonstrate how far the form can be taken.

Just as it did in Geographies of a Lover, de Leeuw’s 2012 poetry collection (which won the Dorothy Livesay Award in the BC Book Prizes), form plays a key role in the writing. These aren’t the essays your high school teacher sought; these twist and turn, unfolding on their own trails, leading the reader into unexpected and often dark places.

The first piece opens playfully, teasing us to join in — to enter an old game, “Spot the Lie.” But trying to figure out which part of what she says is false pulls us into the next section, which is anything but a game. As she leads us through the various parts of the piece, we begin to see just how much is afoot. She writes, almost slyly, “You have begun to understand things you never dreamed of knowing.” The essay goes on through several other seemingly disparate sections, a what-would-you-wish-for exercise that left me broken-hearted, and ends with her writing about a subject she knows all too well, the story of a marginalized woman who’s been murdered.

Marginalized. Such a safe word. Like cutesy squiggles drawn in at the side of the page, maybe in neon-green felt pen. But safe isn’t the tack de Leeuw chooses to take. That’s just me, needing to feel safe, backing away from the harsh truths that lie within the pages of this thin book.

Authentic would be a better word for de Leeuw’s kind of writing. Hers is a voice that rings true, at least partly for the fact that she has worked with people we gingerly call “marginalized” — in safe houses and prisons, or with outreach societies. She’s lived in the north, where so many of us Lower Mainlanders have never made the time to even visit. She knows, from the inside, the small towns where too many people have nothing to hope for. Such authenticity of voice generates power for the things she has to say.

And “has to say” is what I mean — not “has” as in “possesses” or “owns” but “has” as in “must.” This is writing that bears witness to so many of the ills of our world, especially here in the world of British Columbia, which not long ago our brazen leaders dared to try calling the “Best Place on Earth.”

One of the methods she uses to achieve the role of witness is through the device of two parallel stories, each often innocent-seeming enough, like rails that might take us to some wonderful place. In “Seven in 1980” we are given glimpses of a happy-sounding childhood, filled with holiday trips and the excitement of sleepovers. Beside this runs an account of small scientific queries, with questions about topics ranging from moths and what they eat (and the discovery that they feel furry) to wondering about Neapolitan ice cream and how “…all the flavours get into one container together.”

You could almost imagine this essay like a Science Fair project with its accounts of Pompeii (right down to the image of the little dog and his master, frozen in lava for the ages) leading, as we know it will, to the eruption of Mount Saint Helens. But volcanoes (and even the shudders of earthquakes) aren’t the catastrophe the essay brings us to.

When the news reports that a twelve-year-old girl has been abducted — twelve, an age she as a seven-year-old has longed for — everything shifts. Fears rock her world to the point where she decides growing up may not be the magic carpet ride she’s imagined it to be. “…I suddenly longed to not be growing up. I thought about before being seven, about lakes and spectrums of heat and light and my father and my mother and everything a seven-year-old wants never to lose.” Innocence. A word that never lasts quite long enough.

Poet that she is, de Leeuw knows how to use the sounds of words to her advantage. This is especially evident in the essay “Quick-quick. Slow. Slow.” Purportedly about the city of Prince George, it could apply as a lament for any once-booming town with a resource-based economy. The piece is built on the rhythms of the two-step, a structured dance one needs to know (as I learned, the hard way, through a veil of embarrassment) if you venture nearly anyplace beyond our mega-urban centres.

One-two, one-two. Quick-quick with a slow, slow, right-angled slide around the corner, close your eyes and trust your man.

Slow. Slow. These are the steps of a city going soft with middle age. Slow now the dams are in place, slow now the trees are second and third growth and the natural gas is lessening and the fish are disappearing and grasses and cattails are filling in the railway tracks.

It’s not surprising this collection was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for Non-fiction in 2017. The only part that surprises me is that it didn’t win. Maybe it was the occasional typo that did it in. Maybe it was deemed too “regional” to win a national prize.

As for why it didn’t win the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize in this year’s BC Book Award, I don’t have any particular theories. Maybe, maybe, maybe. The world is full of maybes.

Yet one thing I am sure of is that the world needs more writers who are unafraid to write in ways that help us see as much and as clearly as Sarah de Leeuw does. I want more books and essays that will help us see those things we too often try to pretend aren’t there — all those big and small lies we choose to ignore.

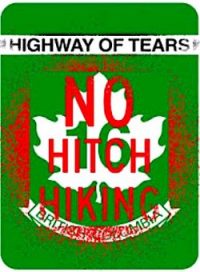

This collection is a book that’s built on memories — of the author’s hard-working Oma, of a family dog gone astray, of people for whom home is a tiny room in a hotel where the bathroom is down the hall. It’s a journey along the Highway of Tears, a trip to the land of growing up best friends with a person you love into adulthood. Memories, many sad ones, ones that will remind you of memories of your own — and, I suspect, of exactly “where it hurts.”

*

Heidi Greco is a writer, editor, sometimes-instructor and a volunteer who works with incarcerated men at Surrey Pre-Trial Centre. In 2017, Caitlin Press published Flightpaths: The Lost Journals of Amelia Earhart – a collection of journal entries, poems, and letters presented as if they’d been written by the famous pilot. In spring 2018, she edited From the Heart of It All: Ten Years of Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Otter Press). This fall, a new collection of poems, Practical Anxiety, is forthcoming from Toronto’s Inanna Publications.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

Leave a Reply