#350 Naval giants of the Great War

August 23rd, 2018

Churchill and Fisher: The Titans at the Admiralty who fought the First World War

by Barry Gough

Toronto: James Lorimer, 2017 (Seaforth £35)

$39.95 / 9781459411364

Reviewed by James Wood

*

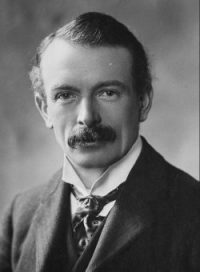

Barry Gough of Victoria continues his torrid pace and high-quality output with the publication of his character study, Churchill and Fisher: The Titans at the Admiralty who Fought the First World War, a 656-page dual biography of the political head of the Royal Navy, Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty), and the professional master of the navy, John Arbuthnot Fisher (First Sea Lord).

Barry Gough of Victoria continues his torrid pace and high-quality output with the publication of his character study, Churchill and Fisher: The Titans at the Admiralty who Fought the First World War, a 656-page dual biography of the political head of the Royal Navy, Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty), and the professional master of the navy, John Arbuthnot Fisher (First Sea Lord).

Writing in the Times Literary Supplement, Jan Morris has declared Barry Gough’s dual biography about the early 20th century relationship between Churchill and Fisher as “enthralling” and “a work of profound scholarship and interpretation.”

As Gough investigates how the two friends clashed over World War One strategies, he delves deeply into the collisions of their temperaments, describing the work as “an inquiry into . . . the role of personality and character in the making of history” chiefly when Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty, the Navy’s political chief, and Fisher was its First Sea Lord, its professional chief. The book chiefly arose from access to Jacky Fisher’s papers.

In June 2018, Churchill and Fisher was announced the co-winner of the Keith Matthews Award of the Canadian Nautical Research Society for best book published in 2017. Ormsby Review readers might recall the other 2018 Matthews Award winner was Michael and Anita Hadley’s Spindrift: A Canadian Book of the Sea (Douglas & McIntyre) that was reviewed by Theo Dombrowski in The Ormsby Review (#196, November 6, 2017).

Reviewer Jim Wood notes that the primary focus of Churchill and Fisher is “the contributions, and failings, of two titans of the British Admiralty whose exceptional strengths were based on the same characteristics that led to their greatest weaknesses.” – Ed.

*

James Wood’s Review: Barry Gough’s Churchill and Fisher features two particularly strong qualities, the first being that it presents a fascinating story of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill and First Sea Lord John Fisher, or as Gough affectionately terms them, “the daemonic duo.” Gough argues that these two exceptionally strong, authoritarian, intelligent, and forward-looking men were the greatest of partners at the time when the Royal Navy needed them most.

James Wood’s Review: Barry Gough’s Churchill and Fisher features two particularly strong qualities, the first being that it presents a fascinating story of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill and First Sea Lord John Fisher, or as Gough affectionately terms them, “the daemonic duo.” Gough argues that these two exceptionally strong, authoritarian, intelligent, and forward-looking men were the greatest of partners at the time when the Royal Navy needed them most.

Secondly, the author himself has unparalleled qualifications. Not only has Gough written several naval and imperial histories, but as resident Archives Fellow at Churchill College, Cambridge, he attained unfettered access to the holdings of the Churchill Archives Centre. Along with several visits to the UK over the past twenty years, he has been able to conduct an extensive evaluation of the comprehensive manuscript papers of both Fisher and Churchill.

A resident of Victoria, Gough has many close ties to the United Kingdom. He is a Fellow of King’s College, London, and of the Caird National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and is closely associated with The National Archives in Kew, Surrey. Churchill and Fisher represents the first full use of the archival collections of the two “naval titans,” with Gough also drawing on the expertise of famed naval and biographical historians, including Arthur J. Marder, Stephen Roskill, Julian Corbett, and Martin Gilbert.

Gough states that this work “is an inquiry into the psychology of military competence and the role of personality and character in the making of history” (p. xvii). As such, he traces the complex interrelationships between politics, expertise, philosophy, alliances, traditions, and moral factors with an eye to determining how these influenced significant decisions during the war. Interwoven into his study of personal factors, however, are intricate details of naval strategy and the impact Fisher and Churchill had on naval technology, particularly with the introduction of dreadnought battlecruisers and battleships, with their 15-inch guns, enhanced armour and speed capabilities, and the impact of the conversion to oil (from coal) and its subsequent effect on imperial relations with oil-producing countries.

Gough states that this work “is an inquiry into the psychology of military competence and the role of personality and character in the making of history” (p. xvii). As such, he traces the complex interrelationships between politics, expertise, philosophy, alliances, traditions, and moral factors with an eye to determining how these influenced significant decisions during the war. Interwoven into his study of personal factors, however, are intricate details of naval strategy and the impact Fisher and Churchill had on naval technology, particularly with the introduction of dreadnought battlecruisers and battleships, with their 15-inch guns, enhanced armour and speed capabilities, and the impact of the conversion to oil (from coal) and its subsequent effect on imperial relations with oil-producing countries.

At the centre of intrigue, naval estimates, loyalty, betrayal, and technological innovation is the relationship between First Lord Churchill and First Sea Lord Fisher. Through a close examination of their rise and fall, Gough creates the history of the British naval war “at home” and its ramifications for the actual battles at sea.

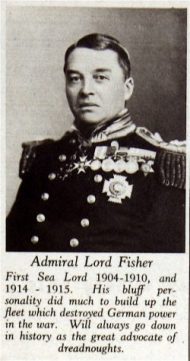

As First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill was the political head, responsible to the sovereign and Parliament. His role was persuasion, one that he carried out forcefully in spite of constant reluctance by fellow Cabinet members to face harsh, unpalatable realities — especially those dealing with rising naval expenditures. Fisher, as First Sea Lord, was the top operational admiral. He was the experienced naval expert, responsible for giving advice to the First Lord on operations, policy, and disposition of the Grand Fleet. Then in his seventies, Fisher had risen through the Navy with a reputation of genius for hard-hitting reform that placed the needs of the dreadnought race as the foremost priority.

The youthful Churchill, about forty years Fisher’s junior — but also his political boss — was noted for his energy, imagination, quick action, and determination. Both saw war coming years before most of their colleagues did, and together they were credited for having the Britain’s Royal Navy ready for war when hostilities broke out in August, 1914. Both were forceful, excitable, and confident of their own unfailing brilliance.

Gough skillfully outlines the bitter complications of their fall from power after the failures of the Dardanelles campaign of 1915. Eventually, Fisher disavowed the campaign and resigned in a disgraceful manner, falsely claiming he had opposed the operation from the start. Standing alone, keeping strategic plans to himself, concludes Gough, “was the essence of the man, and his charm and his danger. Here too, lay his reputation, and in the end, his undoing” (p. 101). Fisher’s startling move brought about a crisis in government, forcing Prime Minister Herbert Asquith to form a coalition with Conservatives dominated by Andrew Bonar Law, who demanded that “Churchill must go” (p. 386). Thus, the “daemonic duo” fell from power in May 1915.

A recently produced documentary presents a theory that “Churchill and Fisher wanted each other’s job” (“Churchill,” pbs.org). Gough’s work, however, reveals that it is more likely that Churchill wanted to do both jobs himself. From the days of the South African War he was noted for being impatient and over-stepping his bounds, both in war and in Parliament. The Agadir Crisis of 1911 had catapulted him to power as First Lord, and from the beginning he had been known to interfere in all levels of the Admiralty — with colleagues and subordinates alike. As Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George complained, “Winston is less and less in politics and more and more absorbed in boilers” (p. 167).

Fisher had also warned Churchill he would resign unless the First Lord interfered less in the work of the Sea Lords — but this fell on deaf ears (p. 344). In 1917, Lloyd George, now prime minister, ignored the protests of Bonar Law and invited Churchill to return to Cabinet as Minister of Munitions. Churchill’s Aunt Cornelia took the opportunity to warn her nephew: “My advice is to stick to munitions and don’t try & run the Govt” (p. 456).

Churchill and Fisher is an impeccably researched, valuable contribution to British naval history and studies of the First World War era. As the title suggests, its primary focus is on the contributions, and failings, of two titans of the British Admiralty whose exceptional strengths were based on the same characteristics that led to their greatest weaknesses. In spite of those failings, the British Navy eventually prevailed in withstanding German unrestricted submarine warfare and underwater mines to enforce a blockade that was significant in bringing the enemy to starvation and surrender.

Surprising in the book are Gough’s revelations of the chaos within the British Cabinet and the Admiralty in struggling to formulate strategy and policy, faced by a war for which they had little experience and even less understanding. Fisher often advocated that “one man” was needed for leadership and insightful decisiveness. Fisher had himself in mind, believing that after Churchill’s dismissal from Cabinet he himself would be invited back as a “superminister” of war (p. 390). However, it was Lloyd George who would ultimately come closest to being that “one man” who could bring order and a coordinated war policy.

Surprising in the book are Gough’s revelations of the chaos within the British Cabinet and the Admiralty in struggling to formulate strategy and policy, faced by a war for which they had little experience and even less understanding. Fisher often advocated that “one man” was needed for leadership and insightful decisiveness. Fisher had himself in mind, believing that after Churchill’s dismissal from Cabinet he himself would be invited back as a “superminister” of war (p. 390). However, it was Lloyd George who would ultimately come closest to being that “one man” who could bring order and a coordinated war policy.

As well, Gough dispels the myth that Churchill alone was to blame for the failure of the Dardanelles campaign. In decisive detail, he outlines roles played by the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, alongside Prime Minister Asquith, several admirals in the Mediterranean theatre, and the changing international circumstances as significant factors in bringing about the closure of the naval campaign just one day before it may have had a war-altering impact (pp. 329-331).

For the titans at the Admiralty there had been no glorious Trafalgar, but with the foundations Churchill and Fisher laid, the Grand Fleet of the British Navy was able to maintain the security of the British Isles, keep the necessary food and war supplies arriving, preserve British trade routes and power, and blockade Germany. “This they did,” Gough effectively shows, “with unremitting zeal in the years of greatest challenge” (p. 493).

*

Dr. James (Jim) Wood has taught history at several post-secondary institutions across Canada, including Trent University, the Royal Military College of Canada, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, UBC Okanagan, and the University of Victoria. In addition to articles published in Canadian Military History, The Journal of Military History, The American Review of Canadian Studies, and BC Studies, his book publications include We Move Only Forward: Canada, the United States, and the First Special Service Force, 1942-44 (Vanwell Publishing, 2006) and Militia Myths: Ideas of the Canadian Citizen Soldier, 1896-1921 (UBC Press, 2010). He teaches history at Okanagan College.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply