#30 Susan Musgrave

December 08th, 2015

LOCATION: Copper Beech House, 1590 Delkatla Road, Masset, Haida Gwaii

Susan Musgrave has been the guest house proprietor and owner of the historic Copper Beech House on Haida Gwaii since 2010, leading her to produce, A Taste of Haida Gwaii: Food Gathering and Feasting at the Edge of the World (Whitecap 2015). More than a cookbook, it has 125 photos of nature and island life, as well as her unparalleled wit, as delicious as any recipe. Here the poet, editor, novelist, critic, essayist and humourist takes a typically amusing detour from cuisine to talk about salmon fishing:

“The English poet Ted Hughes, who came often to northern British Columbia to fish for steelhead, had a theory (widely held, it turns out) that salmon are sexually attracted to female anglers. Because the biggest salmon are cock fish (old word for male Atlantic salmon – one I am so glad I have discovered!) they are naturally attracted to a woman’s pheromones, which transmit themselves to the water when she smears them on her bait or lure in the process of handling her fishing tackle. Old Ted told me he frequently went fishing in Ireland with a friend who tied his salmon flies using his girlfriend’s pubic hair.

“I’ve yet to find a fisherman friend who has begged me to rub his flies in my knickers (that sounds complicated) in order to give him an edge, but I experimented once by wiping a lure through my hair (public, not pubic) when Jim Fulton and I went to the place he called the Meat Hole on the Tlell River. He caught a whopping big Coho on his first cast; I don’t know if it was my pheromones, or the Meat Hole living up to its fecund reputation.”

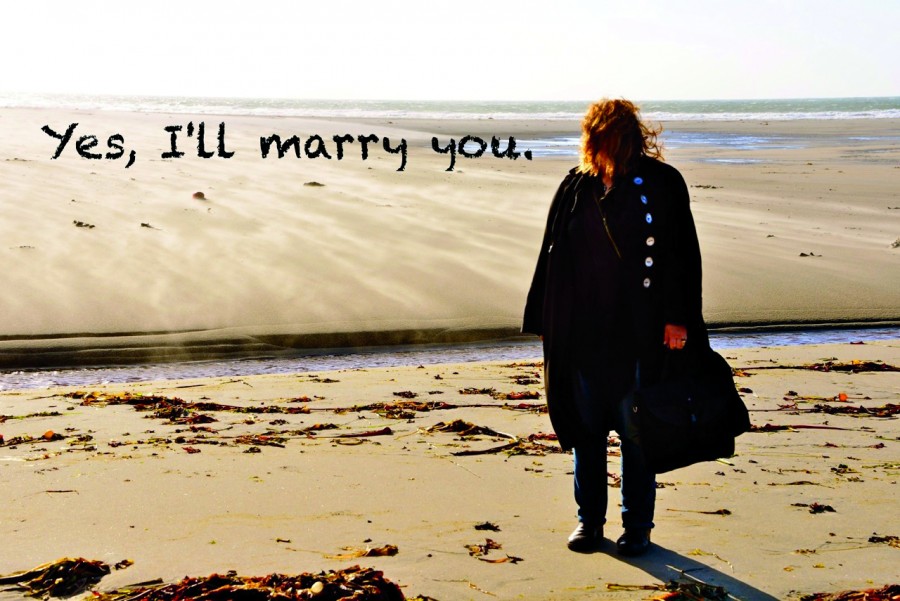

Musgrave has dubbed herself the ‘solemnizer’ since she became an accredited marriage commissioner.

—

by Keven Drews

In her latest literary feast, A Taste of Haida Gwaii: Food Gathering and Feasting at the Edge of the World (Whitecap Books $34.95), readers are able to savour recipes for Shipwrecked Chicken Wings or a famous politician’s Rustled Beef By Gaslight. We can learn how to bake her coveted sourdough or hear the tale of a local fisherman who offered an exotic dancer 50 pounds of shrimp to spend the night with him.

“Our mistakes make the best stories, and that’s why we should not think of them as failures,” says Musgrave.

Musgrave bought the Copper Beech House from her friend, David Phillips in 2010. The building was moved to its current site in the early 1930s.

Inside, heirloom-quality furniture has been replaced with the kinds of things Musgrave says guests can sink into, and a glass curio cabinet displays soapstone geese, an ivory tusk, a rodent skull and a plastic smurf.

Covering the walls are the works of Haida artists, an African penis gourd, antique fishing rods and a sardine can depicting The Last Supper.

Filling the shelves are the books of David Suzuki, Margaret Atwood, Graeme Gibson, Douglas Coupland and William Gibson, all guests of Copper Beech House.

“I can’t say I was cut out to be an innkeeper,” says Musgrave. “I feel uncomfortable most of the time, charging people for a place to lay their head.”

Perhaps, it’s because, as Musgrave says, her father would charge, “you’re so useless you can’t boil an egg,” every time she began to prepare a meal as a child.

“At Copper Beech House breakfast is often a leisurely all-morning-long event,” she writes. “If there are more than four guests we don’t set the table—everyone sits in the living room with a plate on their lap. The informality leads to wonderful stimulating conversations and lets our guests get to know one another without having to worry about which knife or fork to use, or if they spilled stewed rhubarb on the white tablecloth.

“We serve what I have humorously taken to calling an Off-the-Continental Breakfast (Haida Gwaii is about 100 km (60 miles) off the coast of Canada, as Islanders like to say when they refer to mainland British Columbia) which includes many kinds of coffee, every kind of tea, orange juice laced with elderflower cordial, fresh fruits (including local wild berries, when in season), homemade granola, yoghurt and Susan’s 3-day Sourdough Bread… Guests usually go for the bread, partly because it takes me so long to make they would feel guilty if they didn’t eat it, especially after I have reminded them of all the time and effort involved.” 978-1770502161

—

QUICK REFERENCE BIO:

Born in 1951, Susan Musgrave has been one of the most prolific, hard-working and written-about writers of British Columbia. She is a fourth-generation Vancouver Islander who has spent extended periods living in Ireland, England, Haida Gwaii, Panama and Colombia—always outside the mainstream. In one of her brilliant and amusing personal essays, she writes, “In our culture, these days, there is no core, no authenticity to our lives; we have become dangerously preoccupied with safety; have dedicated ourselves to ease. We live without risk, hence without adventure, without discovery of ourselves or others. The moral measure of man is: for what will he risk all, risk his life?”

Susan Musgrave has taken risks. While married to Victoria lawyer Jeff Green, she became involved with one of his clients, an accused drug trader. She later married Stephen Reid, a convicted bank robber, in 1986. After she rescued Reid from prison and gave him a literary life, he reoffended and was incarcerated again. Their story was front page news.

Unfortunately this public side of Musgrave’s risk-taking threatens to obscure her record of excellence as an irresistibly thoughtful, clever and entertaining author of more than 30 titles. It does not help that no particular Musgrave poetry collection or novel stands out as superior to her other works and she has yet to win a major prize for a particular book.

Although Musgrave has been largely out of the public eye in the 21st century, her remarkable range and wit as a poet, editor, novelist, critic, essayist and humorist endures. Along with the experimentalist bill bissett and logging poet Peter Trower, Musgrave has been the embodiment of the maverick, unclassifiable, non-university-coddled B.C. literary tradition that is far more attuned to Haight-Ashbury than Yonge & Bloor. Like Anne Cameron in Tahsis, Musgrave has veered away from urbanity, away from anything “safe.” Meanwhile her novels The Charcoal Burners (1980), The Dancing Chicken (1987) and Cargo of Orchids (2000) and her noteworthy poetry collections, such as Songs of the Sea-Witch (1970), Grave-Dirt and Selected Strawberries (1973) and A Man to Marry, a Man to Bury (1979), will likely be anthologized for many years to come.

In 2014, Susan Musgrave was honoured with the $20,000 Matt Cohen Award from the Writers Trust to mark a writing career that spanned 30 years and produced 27 published works of poetry, fiction, non-fiction and children’s literature.

FULL ENTRY:

Susan Musgrave is easily one of the most humourous writers in Canada, if not the wittiest. Born March 12, 1951 in Santa Cruz, California (of Canadian parents), she is a fourth-generation Vancouver Islander who spent extended periods of time living in Ireland, England, the Queen Charlotte Islands, Panama and Colombia.

The story goes that Musgrave was in a psychiatric ward in Victoria at age sixteen when the eccentric poet and professor Robin Skelton visited her and pronounced that she was not mad, simply a poet. With Skelton’s managerial involvement, her first poetry collection, Songs of the Sea-Witch (1970), was released when she was still a teenager. Skelton’s comrade for his flea market quests, critic and poet Charles Lillard, referred to Musgrave’s second poetry book, Entrance of the Celebrant (1972), as “the first attempt by a woman to merge poetically with the landscape.”

While married to Victoria criminal defence lawyer Jeff Green, she became involved with one of his clients, an accused drug trader, Paul Nelson. When he was acquitted due to Green’s diligence, she and Nelson went to Mexico together, eventually resulting in her second marriage. Her daughter Charlotte Musgrave was born in 1982. After Nelson was incarcerated for a previous smuggling charge and he found God, Musgrave divorced him.

After convicted bank robber Stephen Reid sent her a manuscript from Millhaven Penitentiary in Ontario, where he was serving a 20-year sentence for his career with the Stopwatch Gang–so-named because they relied on efficient planning for their 90-second bank heists-Susan Musgrave became enamoured of Reid while serving as his writing tutor. They were married in Kent Prison in Aggasiz in 1986. With her assistance, Reid was released in 1987.

After the couple was ensconced in her 900-square-foot seaside cottage near Sidney, built by Ernest Fern, a poet, in 1929, her second daughter, Sophie Musgrave Reid, was born in 1989. The Sidney residence has a 190-foot Douglas Fir growing inside. No less unusual was the couple’s shrine to the notorious Colombian drug cartel kingpin, Pablo Escobar, or Musgrave’s overtly conspicuous red car festooned with hundreds of attached figurines. Susan Musgrave and Stephen Reid were the subject of an hour-long CBC (Life & Times) documentary, The Poet and the Bandit, in January or 1999.

After the couple was ensconced in her 900-square-foot seaside cottage near Sidney, built by Ernest Fern, a poet, in 1929, her second daughter, Sophie Musgrave Reid, was born in 1989. The Sidney residence has a 190-foot Douglas Fir growing inside. No less unusual was the couple’s shrine to the notorious Colombian drug cartel kingpin, Pablo Escobar, or Musgrave’s overtly conspicuous red car festooned with hundreds of attached figurines. Susan Musgrave and Stephen Reid were the subject of an hour-long CBC (Life & Times) documentary, The Poet and the Bandit, in January or 1999.

Dressed in a police uniform, Reid, with an accomplice, re-offended with a Cook Street bank robbery in Victoria on June 9, 1999, pointing a loaded shotgun at bank employees and bank patrons. The pair fled with $97,000. Reid reportedly fired at police with a 44-magnum handgun and held civilians at gunpoint after taking refuge in their apartment. On December 21, 1999, he was sentenced to another 18 years in prison. At age 63 in 2014, Reid was granted day parole at a hearing at William Head Institution in Metchosin. He has since revisited Musgrave in Masset.

Musgrave is one of the most prolific, hard working and written-about writers in Canada with a love/hate relationship with publicity. Musgrave has been nominated, and has received awards, in five different categories of writing: poetry, fiction, non-fiction, personal essay, children’s writing and for her work as an editor, but she has yet to win any major prize. The Charcoal Burners was a finalist in the Seal First Novel Competition and was shortlisted for a Governor General’s Award. Things That Keep and Do Not Change was included on The Globe and Mail’s Best 100 Books of the Year List for 1999 and made her a finalist for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize in 2000. A Man To Marry, A Man to Bury was shortlisted for a Governor General’s Award. Grave-Dirt and Selected Strawberries was shortlisted for a Governor General’s Award. Great Musgrave was shortlisted for the 1990 Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour. Nerves out Loud was shortlisted for the Norman Fleck Award. In 1996 she received the Tilden (CBC/Saturday Night) Canadian Literary Award for Poetry and the Vicky Metcalf Short Story Editor’s Award. Her poetry, essays and fiction have appeared in innumberable anthologies. As a columnist, she has appeared bi-monthly in the Toronto Star, Vancouver Sun, STEP Magazine (Vancouver) Cut To: Magazine, Victoria, Sidney Review (1988-1991) and in the Ottawa Citizen (Op-Ed page) September 2001- March 2003. She reviews frequently for the Vancouver Sun and Ottawa Citizen. She has served on dozens of writing juries and performed at hundreds of readings since 1975. Musgrave’s brilliant and amusing personal essays in You’re in Canada Now… are also irresistibly thoughtful. “In our culture, these days, there is no core, no authenticity to our lives; we have become dangerously preoccupied with safety; have dedicated ourselves to ease. We live without risk, hence without adventure, without discovery of ourselves or others. The moral measure of man is: for what will he risk all, risk his life?”

Increasingly at home on the Sangan River, ten miles from Masset, Susan Musgrave lives in a seven-sided house built of logs obtained by local beachcomber Paul Bower. After he died of lung cancer, she produced a modest but intense collection of reflections and “mindful blessings” called Obituary of Light: The Sangan Meditations (Leaf $19.95), mostly recording the natural world around her and her respect for a dying friend. “Some days just listening to him / breathe would be enough to suck / the breath out of sorrow. We all knew / he wasn’t ready to accept / the earth.

BOOKS

Fiction

Given (Thistledown 2014) $19.95 978-1-927068-02-1

Cargo of Orchids (Knopf, 2000, trade paper edition, Vintage, 2001)

The Dancing Chicken (Methuen, 1987)

The Charcoal Burners (McClelland & Stewart. 1980, paperback by Totem in 1981)

Poetry

Origami Dove (McClelland & Stewart, 2011)

Obituary of Light: The Sangan Meditations (Leaf Press 2009) 978-1-926655-01-7

What the Small Day Cannot Hold: Collected Poems 1970-1985 (Beach Holme, 2000)

Things That Keep and Do Not Change (McClelland & Stewart, 1999

Forcing the Narcissus (McClelland & Stewart, 1994)

The Embalmer’s Art: Poems New and Selected (Exile Editions,1991)

Cocktails at the Mausoleum (McClelland & Stewart, 1985; Beach Holme, revised edition, 1992)

Tarts and Muggers: Poems New and Selected (McClelland & Stewart, 1982)

A Man to Marry, a Man to Bury (McClelland & Stewart,1979)

Becky Swan’s Book (Porcupine’s Quill, 1978)

Selected Strawberries and Other Poems (Sono Nis Press, 1977)

Kiskatinaw Songs (Pharos Press, 1977. With Sean Virgo, illustrated by Douglas Tait

The Impstone (McClelland & Stewart, 1976; Omphalos Press, London, 1978)

Grave-Dirt and Selected Strawberries (Macmillan, 1973)

Entrance of the Celebrant (Macmillan, 1972; Fuller d’Arch Smith, London)

Songs of the Sea-Witch (Sono Nis Press, 1970)

For Children

More Blueberries (Orca, 2015) $9.95 9781459807075. Illustrated by Esperança Melo.

Love You More. Illustrated by Esperanca Melo (Orca 2014) $9.95 9781459802407. Board book

Kiss, Tickle, Cuddle, Hug (Orca, 2012) $9.95 9781459801639. Board book

Dreams are More Real than Bathtubs. (Fiction. Illustrated by Marie-Louise Gay. Orca. 1998)

Kestrel and Leonardo (Studio 123. 1990. Poetry. Illustrated by Linda Rogers)

Hag Head (Clarke, Irwin & Co. 1980. Fiction. Illustrated by Carol Evans.)

Gullband (J.J. Douglas, 1974. Poetry. Illustrated by Rikki Ducornet)

Non-fiction

A Taste of Haida Gwaii: Food Gathering and Feasting at the Edge of the World (Whitecap 2015) $34.95 978-1-77050-216-1

You’re in Canada Now, Motherfucker. A Memoir of Sorts (Thistledown, 2005) $18.95. 1-894345-95-9

Musgrave Landing: Musings on the Writing Life (Stoddart, 1994)

Great Musgrave (a collection of essays and columns; Prentice-Hall 1989)

Editor

Editor for Thistledown Press (Saskatoon, Sask) short fiction, poetry and Y/A titles 1994-2003 (ongoing)

Editor for Justice James Clarke (Exile) poetry (1997-2001)

Editor for Gale Garnett’s Visible Worlds (Stoddart) fiction 1999

and Transient Dancing (MacArthur & Co, 2003)

Editor for Harbour Publishing, fiction 2000

Because You Loved Being a Stranger: 55 Poets Celebrate Patrick Lane (Harbour Publishing, 1994)

Clear Cut Words: Writers for Clayoquot, (Hawthorne Society for Reference West, 1993)

Breaking the Surface (Sono Nis, 2000): Winner BC2000 Book Award

Nerves Out Loud: Critical Moments in the Lives of Seven Teen Girls (Annick Press, Fall 2001; series editor)

You Be Me: Friendship in the Lives of Teen Girls (Annick, 2002)

Certain Things About My Mother: Daughters Speak (Annick, 2003)

Perfectly Secret: The Hidden Lives of Seven Teen Girls (Annick, 2004)

Force Field: 77 Women Poets of British Columbia (Mother Tongue 2013). 400 pages 978-1-896949-25-3 $32.95

Chapbook

In the Small Hours of the Rain, poetry published by Reference West (Victoria) 1991 (winner, First Prize, of b.p. Nichol Poetry Chapbook Award, 1991)

Portfolio

The Spiritualization of Cruelty, six poems with drawings by Pavel Skalnik, limited, lettered and numbered edition, 1992

Pamphlets, broadsides

Many pamphlets (limited editions) from the Sceptre Press in England. From Dreadnaught 52-Pickup, #9 (1976): Between Friends. Taboo Man was published by Celia Duthie, 1981, in a limited edition of 50 signed copies. The Plane Put Down in Sacramento and “I do not know if things that happen can be said to come to pass or only happen” as broadsides, by William Hoffer. Desireless: Tom York (1947-1988) published by Slug Press, 1988; The Situation in Which We are both Amateurs published by Lazara Press, 1998.

SOME AWARDS:

National Magazine Award (silver) 1981

R.P. Adams Short Fiction Award (3rd prize) for “The Remains of

Edward’s”, published in Negative Capability, Mobile, Alabama, 1989

B.C. Cultural Fund Grant, 1991, 1994, 1998

b.p. nichol Poetry Chapbook Award (First Prize) 1991

Readers’ Choice Award for poems published in the Winter 1993 edition of Prairie Schooner

CBC/Saturday Night/Tilden Award for Poetry, 1996 (First Prize)

Vicky Metcalf Short Story Editor’s Award, 1996

Panty Lines: First Prize for Ice-Age Lingerie, 1999

National Magazine Award for “Personal Journalism” in Saturday Night, 2000: Honourable Mention

Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize, Honourable Mention, 2000, for Things That Keep and Do Not Change

THEATRE

Gullband (produced and directed by Paully Jardine) was performed by the Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto (Christmas 1976)and by the Touchstone Theatre in Vancouver (Christmas 1977).

“Valentine’s Day in Jail”, adapted from a novel in progress, Cover Girl, was produced by Ruby Slippers in Vancouver, B.C. in their 1995 production of “Herotica”.

WRITER-IN-RESIDENCE

University of Waterloo, 1983-1985

University of New Brunswick, Summer Session 1985

Vancouver Public Library, National Book Week 1986

Festival of the Written Arts, Pender Harbour, B.C. 1987

Ganaraska Writer’s Colony, Fiction Workshop. June 26 – July 9, 1988

Sidney Public Library, Sidney, B.C. Short-term Writer-in-Residence April, 1989

Ganges High School, Short-term-Writer-in-Residence, November 1989, February 1991

George P. Vanier Secondary School, B.C. Short-term Writer-in-Residency, May 1991

Kaslo Summer School of the Arts, Short-term-writer-in-Residence, August 1991

University of Western Ontario, 1992-1993

Festival of the Written Arts, Sechelt, B.C. November 11-14, 1993, May 23-27, 1994

Writer-in-Electronic-Residence, 1991-1999 (ongoing) (writer online and writer/moderator through York University and the Writers’ Development Trust

Banff Centre for the Arts, November 1994

University of Toronto Presidential Writer-in-Residence Fellowship, 1995

Victoria School of Writing, 1996, 1998

The Ralph Gustafson Chair of Poetry, Malaspina College, Fall 2000

TEACHING POSITIONS

Arvon Foundation, Sheepwash, Devon, 1975: Instructor, with Brian Patten

Arvon Foundation, Lumb Bank, Yorkshire, 1980: Instructor, with Liz Lochead

University of Waterloo, 1983-1984: Instructor, English 335 (Creative Writing)

University of Waterloo, 1984-1985: Instructor, English 336 (Advanced Creative Writing)

Kootenay School of Writing, 1986: Instructor, Creative Writing Workshop

Camosun College, Victoria, B.C.: Instructor, Creative Writing, 1988-1999

Mentor, B.C. Festival of the Arts, 2001

University of Northern B.C., Quesnel, B.C. 2001-2003; Five-day summer (credit) courses in Short Fiction and Poetry

RADIO AND TELEVISION and FILM (Selected)

Profiled on BCTV, December 1985 and October 1986.

CTV LIFETIME October 1986. CBC NEWS September 1987.

CTV LIFETIME Fall 1987. THE JOURNAL, Fall 1987.

BCTV, February 1988. CKVU TV, December 1989.

CANADA IN VIEW (CTV, April 1990)

The Shirley Show (CTV January 1992)

Front Page Challenge (February 1993)

Canada AM (March 1994)

CBC Life and Times: “The Poet and the Bandit” (January 1999)

Heroines (Bravo, 2001): Poetic-script for documentary film on Lincoln Clarkes and the heroin-addicted prostitutes of Vancouver’s lower east-side

“Where Did you sleep last night” (teenagers recruited into the sex trade) and “Truth and Betrayal” (the stress teenagers feel about being expected to keep secrets) – two 15-minute film scripts for the National Film Board’s “Teenagers at Risk” series, 1998

“Valentine’s Day in Jail”, a chapter from a recently completed novel, CARGO OF ORCHIDS, published in Fever and Best American Erotica, 1995 has been optioned by Back Alley Films to be adapted for a half-hour film for SHOWCASE: December 1998.

LYRICS/CD:

“Missing”- a song for the 61 Missing Women of Vancouver’s Downtown eastside – music by Brad Prevadoras, vocals by Amber Smith, 2003

MEMBER: Writers’ Union of Canada (Chair, 1997-1998); B.C. Federation of Writers; Canada Council Advisory Committee, September 1992-1993; Stephen Leacock Poetry Awards Advisory Committee; Writers in Electronic Residence Advisory Committee, and Executive Committee; In 2 Print (magazine for creative people ages 12-20 – Advisory Committee (poetry)

ARCHIVES

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

BIBLIOGRAPHY (CHRONOLOGICAL)

Songs of the Sea-Witch. Victoria, B.C.: Sono Nis Press, 1970.

Skuld. Frensham, Surrey: Sceptre Press, 1971.

Birthstone. Frensham, Surrey: Sceptre press, 1972.

Entrance of the Celebrant. Toronto: Macmillan, 1972.

Equinox. Rushden, Northamptonshire: Sceptre Press, 1973.

Kung. Rushden, Northamptonshire: Sceptre Press, 1973.

Grave-Dirt and Selected Strawberries. Toronto: Macmillan, 1973.

Against. Rushden, Northamptonshire: Sceptre Press, 1974.

Two poems. Knotting, Bedfordshire, England : Sceptre Press, 1975.

The Impstone. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1976.

Kiskatinaw Songs, with Sean Virago. Victoria, B.C.: Pharos Press, 1977.

For Charlie Beaulieu in Yellowknife who told me to go back to the south and write

another poem about Indians. Knotting, Bedfordshire, England : Sceptre Press, 1977.

Selected Strawberries and Other Poems. Victoria, B.C.: Sono Nis Press, 1977.

Two poems for the blue moon. Knotting, Bedfordshire, England : Sceptre Press,

1977.

Becky Swan’s Book. Erin, On: Porcupine’s Quill, 1978.

A Man to Marry, a Man to Bury. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1979.

Conversation during the Omelette auz Fines herbes. Knotting, Bedfordshire:

Sceptre press, 1979.

When my Boots Drive off in a Cadillac. Toronto: League of Canadian peots, 1980.

Tarts and Muggers: Poems New and Selected. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982.

The Plane put Down in Sacramento. Vancouver: Hoffer, 1982.

I do not know if things that happen can be said to come to passs or only happen.

Vancouver: Hoffer, 1982.

Cocktails at the Mausoleum. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart,1985.

Desireless: Tom York (1947-1988). Celia Duthie, 1988.

In the small hours of the rain : poems. Victoria, B.C. : Reference West, 1990.

The Embalmer’s Art: Poems New and Selected. Exile Editions, 1991.

Forcing the Narcissus. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1994.

Things that keep and do not change. Toronto : McClelland & Stewart, 1999.

Cargo of Orchids (Knopf, 2000, trade paper edition, Vintage, 2001)

What the Small Day Cannot Hold: Collected Poems 1970-1985 (Beach Holme, 2000)

Origami Drive (M&S 2011). Poetry. 978-0-7710-6522-4 $18.99 Can.

Love You More (Orca). Illustrated by Esperanca Melo. For infants.

Kiss, Tickle, Cuddle, Hug (Orca). Illustrated by Esperanca Melo. For infants.

More Blueberries (Orca 2015). Illustrated by Esperanca Melo. For infants. $9.95 978-1-4598-0707-5

A Taste of Haida Gwaii (Whitecap 2015) $34.95

=======

Set in the near future, when executions are broadcast on television, Cargo of Orchids is wonderful fun; terrifying, unforgettable and sui generis.

On the surface Cargo of Orchids is a conventionally structured story about a nameless woman, condemned on Death Row for ten years, who finally gets permission to write down how she got there. Her life and times and routines and rituals in the death house are as important as the series of disasters that brought the narrator to Heaven Valley State Facility for Women.

By turns blackly funny and numbingly real, Musgrave takes on the task of delineating violence done to women and violence done by women. As settings, she uses male and female prisons, and the drug-based Hell-Heaven of the Caribbean island called Tranquilandia, a place so exploitive and evil that it might have been invented by a multinational shoe or rug company.

The protagonist’s actions are fueled by her vulnerabilities and her needs, but Musgrave’s intent here is not allegorical. Her women are weak for understandable reasons, or they are strong and blithely murderous for equally understandable reasons. Utter disregard for the sanctity of human life when money/power/revenge must be served is the engine of this narrative. The condemned woman’s life before being sentenced to death is searingly done; so is her minute-by-precious-minute existence on Death Row. The reader is taken back and forth between these two lives by a writer who knows precisely what she’s doing and has the skill to do it. The black stand up routines of Rainey and Frenchy and the nameless narrator (made murderers by their rage and despair) are comic relief, but they are also a way of making the reader listen, and perhaps understand, what it is to be condemned to arbitrary deaths.

You may, as I did, find the last 435 words of the novel a bit of a shock. Perhaps Knopf persuaded the author that deus ex machina instead of the logic of the narrative would sell better. The harm, as I see it, is not terminal. You need only give yourself up to the thrust of the rest of the book and go easily into the novel’s intended dark night on your own. 0-676-97285-3

[Robert Harlow / BCBW 2000]

It’s been suggested—by people who don’t know her—that Susan Musgrave must get some of her inspiration from dealings with institutions such as maximum security penitentiaries and public schools.

Perhaps it was Musgrave’s school memories, coupled with the child-accurate expressions of her young daughter Sophie, that have led to Dreams Are More Real Than Bathtubs (Orca $17.95).

The narrator, about to tackle Grade One, recalls her dreams — Mum as a witch, the fear-us tiger, and flying over her new school in a red bathtub as a stuffed Lion pulls the plug.

Morning comes and she eats breakfast with ‘one gone tooth’ and heads to school where bullies say ‘sunnish Lion’ looks ‘bumish-colour’ to them. At recess she sings, “All the kids hate me.”

The day improves at lunch when our plucky heroine meets her new best friend who has a ‘stuffy’ herself named Seal.

Tomorrow’s looking good. She’ll bring Old Mum for Show ‘n’ Tell. She’ll say, “I got her when I was very small.” And she’s not just dreaming.

The little girl bounces over the word trampoline and crawls through the dirt as a worm. Marie-Louise Gay, known for her work on Lizzie’s Lion and Moonbeam on a Cat’s Ear, has wrapped her lively illustrations seamlessly around the text.

The tiger is ‘fear-us’ (fierce). And Old Mom wears the grin of a versatile and gifted writer who just might have been shortlisted for a Governor-General’s Award four times. 1-55143-107-6

[BCBW WINTER 1998]

Things That Keep and Do Not Change (M&S $14.99) is a book with a scary undercurrent. Tapping into fears and subconscious yearnings has been Susan Musgrave’s trademark from her earliest work, Songs of the Sea Witch, where she found inspiration and direction in classical and aboriginal mythology. Now she is able to locate the mythic element anywhere, in a death, a ferry ride, a failed photographic expedition, even in reading someone’s else’s collected poems!

Poetry, for Musgrave, is a survival technique, a healing process, which involves giving not only shape, but also, at times, the finger to our violent and deviant imaginings. The book contains a fine poem about parental fears of harm to a child, as well as various touching elegies and tributes to friends. The title section, which will be recognizable to those familiar with her earlier work, focuses on male aggression, its rationalizations and consequences. This section, which derives much of its power from humour, satire, even whimsy, can cut to the quick, shifting from disembodied voices in pain to hilarious superstitious assertions.

“Praise,” one of her most striking poems, is an ironic monologue by the daughter of a burned witch who sees all too clearly the link between sex and violence. It’s a finely tuned poem, written in a flawlessly colloquial voice, and knitted together by variations on the verb “burn’ which apply not only to the treatment of witches, but also to the extremes of male sexual desire. The burning mother’s lemon-coloured scarf is recalled later in the poem when the speaker refers to the sour taste of a wedge of lemon between her teeth. Musgrave uses a figure of speech here—”as her voice carried high into the star-pitched sky”. It’s not a felicitous choice, but is redeemed, more or less, by the deliberate internal rhyme and the highly charged context of the poem. 0-7710-6676-7;

[BCBW SUMMER 1999]

SUSAN MUSGRAVE was born in California of Canadian parents in 1951. She grew up in Victoria. In her earlier work she is not unlike the foreign correspondent on the evening news who reassures us that the rest of the world is indeed in chaos, Subjective poems as precious and desperate as notes in bottles have brought notoriety in Canada and abroad. Her books of poetry include Songs of the Sea- Witch (1970), Entrance of the Celebrant (1972), Grave Dirt and Selected Strawberries (1973), Gull-band (1974, children), The Imp stone (1976), Becky Swann’s Book (1977), Selected Strawberries and Other Poems (1977), Kiskatinaw Songs (1978, with Sean Virgo) and A Man to Marry, A Man to Bury (1979), The Charcoal Burners (1980) was her first novel, a dream-like vision of rituals in a primeval society, It was followed by a comedy of manners, The Dancing Chicken (1987), Susan Musgrave lives in Victoria, She was interviewed in 1980.

T: What are the types of poems that get the most response from people?

MUSGRAVE: The love poems. I met a woman recently who had carried around one of my love poems for six months.

T: Yet you can still question writing as a profession for yourself.

MUSGRAVE: Well, it’s hard for me to get any vicarious enjoyment out of what I’ve written. Once I’ve written it, that’s it. It’s just there to be found for someone else. It doesn’t have much to do with me any more. My problem, being the creator, is that if a poem is really strong, it doesn’t need me any more. It’s like giving birth constantly, and constantly weaning.

That’s not to say I’m only some sort of medium. But I don’t feel I can take the credit very long for something that I have written. People quote great lines of poetry without even knowing who the poet was. That’s how poetry works.

T: Does that mean you would write to create those special lines as much as special poems?

MUSGRAVE: I think so. It’s the line. Individual lines stick in my head. Every poem usually has a couple of lines in it that are better than the rest. Once, around New Year’s, I wrote a poem about looking back at what had happened in the last ten years. Ten years before, I had been in hospital on New Year’s Eve. “My father rocked in his chair, unable to share his last breath with anyone. That was years ago when we didn’t think he would live much longer. He still drives down the highway to see me.” When I showed the poem to a friend, what stuck out for her was the line about my father driving down the highway to see me. For me, that is the whole poem. But I can’t figure out why. That is what is so great and so tricky about poetry. To get that to happen. You can’t really try. It just has to fall into place.

T: When you publish a book, do you wonder what people are going to say about it because you’re wondering yourself about it?

MUSGRAVE: Oh yes, I never really know. I put a book together but I don’t have much idea what I’m attempting it to be. One of my problems has always been this approach. If it works, then it’s great. If it doesn’t work, it’s not so great.

T: But art requires form. My E.M. Forster guide to novel writing says so, so it must be true.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. I’m sure that’s right. I can see there’s a lot more for me to learn about prose than poetry. These days I’m thinking more and more in terms of prose. Even the poems I’m writing are becoming more narrative. I want to be accessible, at least to myself. I figure if I am accessible to myself, then I will be accessible to other people. I admire writers who are accessible.

T: Would you agree much of your poetry functions basically on the level of dream?

MUSGRAVE: Yes. A lot of poems come right out of dreams. Lately I’ve been especially interested in how being in love with someone is very much like being on a dream level. It attacks the same areas of my head as a poem. It’s a kind of vague hit of something, of adrenalin, of psychic energy. I just don’t know what it is. But it’s all connected. In my work I use dreams and being in love the same way. I get the same kind of inspiration from it. It’s quite unconscious.

T: The talent of your poetry then is trusting your instincts to such a pure extent that whatever you write cannot be dishonest.

MUSGRAVE: A lot of my early poems I don’t even understand any more. I get quite embarrassed when people come up to me and ask what’s this poem all about. I just haven’t a clue. In fact, I end up thinking that they’re badly written and I obviously missed the point. I trusted the vision, the spirit and the mood and all those things, but I missed what I was really trying to communicate.

T: Maybe you didn’t know enough about how to properly shape a poem.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. Eliot, when he was older, said he didn’t understand The Wasteland any more. He thought it was a case of having had too much to say and the not the understanding of how to say it. I think that really applies to me when I was nineteen or twenty. I had an amazing amount in me to write about but I wasn’t ever sure really how to do it.

T: Nevertheless, the level of maturity of your first book is really quite exceptional. If you hadn’t gone through that exceptional experience of spending time in a psychiatric ward, would that maturity have come so quickly?

MUSGRAVE: I don’t know. I feel that I was more mature then than I am now. I had some sort of wisdom but I couldn’t cope with it very well. Obviously- because I kept going mad all the time. Which may have meant I was very wise but I wasn’t quite sure how to handle that!

T: Do you get hostile reactions from people because of your witch persona?

MUSGRAVE: Oh, I think so. Yes. People try to make it hokey. They try to make it nonsense. More blood and darkness. More preoccupation with morbidity and death. They try to attach words to it that lessen the impact of what I’m trying to talk about. They don’t tackle the essential ideas of, I suppose, spirituality.

T: Because we have so little training for that.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. Even people who respond positively cannot articulate why they like my poems. It’s like the pioneer mentality, all hard work, make money and get ourselves set. We don’t want anybody saying there’s more to it than just that. Maybe you should just sit and look at the mountains for a day. People can’t be told that. It upsets what they’ve come here to do. So people walk out of a bill bissett poetry reading shaking their heads.

T: Yes. There ought to be a book analyzing Canadian literature from a spiritual poverty angle.

MUSGRAVE: Canadian Literature: A Christian Interpretation.

The theory I’m developing now is that the writer should be slightly afraid of what he’s writing about. When the writer is in too much control, that excess will get communicated. For instance, I think Atwood was too much in control in Life Before Man. I actually liked the book. It was extremely well written. But people couldn’t like the characters because of her control over them. Whereas in Surfacing, I felt the author was afraid. Perhaps a really successful book will have both elements. It will have fear and control.

T: You’re talking about fishing into the subconscious.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. Writing can be likened to fishing. Except I hate fishing. Things never surface for me. I’ve never once caught a fish that carne to the top. The rod bends double. Something’s down there that never comes up. I think how can people go out there and idly catch fish? As if they’re not doing some mystical thing? People always think I’m crazy, but that’s how I feel. You hook the darkness.

T: A novel gives you another world to go into.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. Where The Charcoal Burners fails is that I didn’t come to grips with my fear. The fear overcame me in the end. I didn’t have enough control. I was so anxious to get it over with because I was so frightened. It could have been a novel of nine hundred pages. But I was too terrified. Next time I’d like to get more balance between control and fear.

T: Maybe if you learn more control in your writing, you’ll eventually learn more control over your life. You won’t get possessed by people and things.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. When I’m writing, I’m very calm and happy. I don’t need a quarter as much from the world as when I’m not writing. When I feel those outside attractions happening, I’m not nearly as strong.

T: When you feel that state of being possessed coming on, are you frightened? Or are you expectant? Or do you merely find it intriguing?

MUSGRAVE: A bit of all those things. I get incredibly energetic and ecstatic. That usually is accompanied by a total loss of appetite. And I don’t sleep very much. There’s some sort of overload going on. It’s usually a person I feel I’m possessed by, but it’s very hard to tell somebody, “I am possessed by something in you that you mayor may not recognize or see or know.”

T: So that attraction can be highly impersonal.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. Of course a lot of people are confused by that. Not many people are going to be interested in return. I mean, if somebody does that to me, I don’t think I’m going to be impressed! Matt Cohen, who has known me for a long time, says I don’t fall in love with personalities, I fall in love with what is invisible.

T: That fits, because your poetry is trying to come in contact with what is unrealized, too.

MUSGRAVE: But maybe I’m just projecting onto someone else something that is mine. I attach it to someone else in order to lose it. If I project it hard enough, it can become real. Then when I see that, actually, that special quality in someone else isn’t really there, that I’ve invented it, it’s very disappointing. The magic wears off.

I’m at the stage of wondering what it is I’m doing, what it is I need, why do I keep doing this to people? I was reading something by Jung about poets; he said when poets aren’t writing, they regress. They become children. They become criminals. That describes a lot of my behaviour pretty well.

T: Certainly our image of a poet is someone who is outside society in some way. The falling-down-drunk poet is outside society because society expects self-control. Maybe poets are people who are willing to relinquish control more easily.

MUSGRAVE: I don’t think it’s a case of willingness, though.

T: That shows you how [look at behaviour.

MUSGRAVE: Yes, I don’t believe in words like willingness. I don’t believe, to use your analogy, that people set out to get drunk. I believe that drunkenness happens by accident. Suddenly there you are, drunk. There are men I know who will say, “Let’s go out and get drunk tonight.” I don’t know how to do that. I don’t set out to behave any certain way. Behaviour creeps up and takes over.

T: You get psychologically drunk by accident.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. I don’t like giving up control. My reaction to finding myself in a position of having given up control is usually an extreme one. That reaction causes huge difficulties in my life, and the lives of people around me. I don’t like things to be utterly mysterious to me. Yet at the same time, I suspect there are whole areas of our lives that should remain mysterious. There’s a line in Fowles’ Daniel Martin where he is talking

about his wife and he says that his wife didn’t appeal to the unconscious in him enough to make the relationship work.

T: That’s a heavy one.

MUSGRAVE: Right. You can’t live with someone day after day and have that happen. It has to be a mysterious process. “You can’t catch the glory on a hook and hold onto it.”

T: That has rather depressing implications.

MUSGRAVE: It does. I always want to know, I want to own, I want to keep. Yet there’s that line, “Every time a thing is owned, every time a thing is possessed, every time a thing is loved, it vanishes.” Knowing that, I still want to do those things. I still want to own and possess and control. That’s killing something but it’s also a way of getting on top of something and not being dragged down. Not becoming its victim.

T: Is this why you collect talismans? To get power on your side and have control?

MUSGRAVE: I don’t know. I’ve always had huge collections of things. I found a dried-out lizard on Pender Island just the other day. For years I’ve been collecting these objects, but lately I’m beginning to see that I should trust them more. I’m believing again in power objects.

T: Why do you think people collect things?

MUSGRAVE: To build a little net around themselves. To make external something that is internal. Collected objects reassure people that there is something tangible about life. What’s odd about me is that I collect things that are pieces of bodies that once had life, bones and dried-out things. The reassurance there is that it’s all ephemeral.

T: If you don’t have a body, you can’t be hurt. You might simply be seeking the sanctity of spirituality. Have you ever been religious? Or does that word mean anything to you?

MUSGRAVE: I suppose I am religious. Yes, it does. I went through a phase of being a born-again Christian. I was converted through Bob Dylan! People got incredibly upset. They thought I was a write-off. They thought I was going to start handing them pamphlets. They didn’t understand what it means to be born again. When the light shines on you, it shines on you. It can also stop shining on you.

I used to think of religious people as weak people. I thought it was a weakness to believe in anything. But it doesn’t mean you’re a fanatic to be religious. For instance, Catholicism makes sense to me. One day maybe I’ll become a born-again Catholic for a while. It’s a very powerful force. I don’t believe there are answers. I don’t believe that Christ is the answer. But I believe in all gods. How can I believe in the power of a bone or a lizard skin without believing in Christ?

T: When you were a teenager, did you have any career ambitions to be a writer?

MUSGRAVE: No.

T: Did you have any ambitions at all?

MUSGRAVE: There are two things I’ve always wanted to be. A ventriloquist and a tap dancer. I remember Shirley Temple did some great tap dancing in a film I saw once.

T: Aha. Now this interview is finally getting somewhere.

MUSGRAVE: Yes, I want to die in my ruby red tap shoes! Also I remember I once wanted to be a spy.

T: This is all highly significant. Now tell me, what is common to all these professions?

MUSGRAVE: They’re all disguises, I guess.

T: So being a poet allows you to do all three things at once.

MUSGRAVE: Yes. Projecting the voice, performing, spying. I never thought of that. Here I am, everything I ever wanted to be. I’ve made it.

[STRONG VOICES by Alan Twigg (Harbour 1988)] “Interview”

Susan Musgrave’s amusing and irresistibly thoughtful personal essays in You’re in Canada Now… (Thistledown $18.95) are provocative in style and content: “In our culture, these days, there is no core, no authenticity to our lives; we have become dangerously preoccupied with safety; have dedicated ourselves to ease. We live without risk, hence without adventure, without discovery of ourselves or others. The moral measure of man is: for what will he risk all, risk his life?” 1-894345-95-9

[BCBW 2006]

Two precursors were Women’s Eye, 12 B.C. Women Poets (AIR Press 1974), edited by Dorothy Livesay, and D’Sonoqua: An Anthology of Women Poets of British Columbia (Intermedia Press, 1979), 2 volumes, edited by Ingrid Klassen, including Carolyn Borsman, Marilyn Bowering, Judy Copithorne, G.V Downes, Mona Fertig, Marya Flamengo, Cathy Ford, Maxine Gadd, Leona Gom, Elizabeth Gourlay, Rosemary Hollingshead, Carole Itter, Beth Jankola, Stephanie Judy, Pat Lowther, Nellie McClung, Myra MacFarlane, Floris McLaren, Florence McNeil, Dorothy Manning, Daphne Marlatt, Anne Marriott, Judi Morton, Rona Murray, Susan Musgrave, Marguerite Pinney, Helene Rosenthal, Rolsyn Smythe, Dona Sturmanis, Lorraine Vernon, Phyllis Webb, Carolyn Zonailo.

—

from BCBookLook

Unheralded Joseph Planta has been conducting interviews for his website The Commentary for ten years. Here follows his conversation with Victoria-born, Haida Gwaii resident Susan Musgrave, editor of Force Field: 77 Women Poets of British Columbia (Mother Tongue Publishing) during which Planta exhibits one of the most important skills for any interviewer: knowing how to listen.

Although she lives in a seven-sided house near Masset, Susan Musgrave now teaches in the University of British Columbia’s optional-residency MFA program in Creative Writing. Her most recent poetry collection, Origami Dove, was shortlisted for the Governor-General’s Award. Her most recent novel is Alone. Visit www.susanmusgrave.com. This conversation primarily concerns her landmark anthology that exclusively pertains to living female poets of B.C.

________________________________________

“I was worried,” Planta recalls, “because Musgrave knew little of me, and I’d only read this one recent collection before phoning her up. Prior to the interview, Shelagh Rogers kindly reassured me I’d enjoy talking to Musgrave, that I’d have fun. She was right. We talked about poetry, the women poets of British Columbia, her life and career, her views on education, and more. I told her we’d speak for about twenty minutes, and she said that was just fine; her sourdough bread needed to bake for just that amount of time. When we got to the twenty-minute-mark, she had to put the phone down and turn her baking pans around.”

Susan Musgrave: Good morning.

Joseph Planta: Good morning. Are you at the bed and breakfast you own?

S.M.: No, I’m out at my house out in the Sangam Rive. I’m making sourdough bread, which is like a 36-hour production. It’s a great bartering place up here. People have chickens and they want a loaf of bread. So I’ll trade eggs for bread. I’m getting more famous for my bread than I am for my writing.

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: In a small place, you’re always more famous for what you can do. You know, the jam you make, or the relish you make or the bread you make. I like it that way.

J.P.: How long does it take to get up there?

S.M.: To Masset? Well, you can fly from Vancouver on Pacific Coastal. It’s two hours from the South Terminal to Masset. Or take Air Canada to Sandspit. If you take the ferry, it’s two days and two nights, so that gives you an idea of how far it is. If you go over land, it’s an amazing trip from Port Hardy to Rupert to Skidegate. It’s a long, long trip, which I love doing, because you’ve got the Inside Passage.

J.P.: Do you remember the first time you went to Haida Gwaii?

S.M.: Oh, I do! I was living in Cambridge, in England. We’d moved from the west of Ireland and we weren’t very happy in Cambridge. My publisher, Michael Yates—who had Sono Nis Press, who published my first book—was working in Port Clements as a logger. I had spent a lot of time feeling homesick for the coast, visiting the Ethnology Museum in Cambridge. It was full of stolen artefacts like totem poles from Tanu, and I felt so at home in this museum. I kind of lived there. A lot of the things there made me really want to come here. So when I found out that Mike Yates was here, I came up. It was when I came home for Christmas o on sort of a holiday. As people do, they either fall in love with this place and they want to live here, or they don’t like it. Mostly people say, you know, “There’s something mystical about this place,’”and “It’s a very healing place.” And now my guests at Copper Beech House will say, “It’s changed my life.” I hear that over and over again, which is a pretty amazing thing. I still don’t know, after 40 years of being here, what it is about the place that changes your life.

It takes me about two weeks to decompress after I’ve been down south. When I lived here in the ’70s, it was really like having a love affair. When I would go back down to Victoria, I would go through withdrawal—I would just be wretched. It has that effect; it has as much of a pull as a person you’re in love with. So, if you came here for just four days, you would just get the tip of the affair [laughter]. You’d get…‘Oh, I need more of this!’ And then you’d be back I would guess. Four days. That’s how long Shelagh Rogers was here. They were up here for the Peter Gzowski Golf Tournament. And Linda Cullen and Bob Robertson.

J.P.: It makes me want to go there now.

S.M.: If you only have three or four days, it’s still better than never having been here, right?

J.P: How did you get involved with editing Force Field?

S.M.: Mona Fertig and her husband Peter were guests at Copper Beech House the year I took over. It was a pretty rough year. My daughter was sort of running the place before she got back into her addictive cycle, and so, there were a lot of things going wrong. Anyway, I survived the worst six months of my life, and during that time Peter and Mona came. And Mona proposed this anthology and said, “How would you like to edit it?” I’ll say yes to everything at first until I step back, and then what have I done? So at some point, I said, “No, Mona, I just can’t do this; I think it should be ten poets. I can’t do a hundred and fifty, or seventy, I’d have to leave people out and I don’t want to leave people out. But if we do 75, there’s going to be another 75.” And sure enough, the poet who won the BC Book Award this year, Sarah de Leeuw—she wasn’t in the book. We just had to drop so many people. I thought, whatever you do, somebody will be missed and it’s unfortunate. I want to do a second volume—but I don’t think Mona does. She’s worn out from all the good work she does.

J.P.: And how did you arrive at number 77?

S.M.: [laughter] Well, I really like the number seven. My house is seven-sided. I have three seven-sided modules, and a seven-sided table. I don’t know. We had 75 and then we found three more that we’d forgotten that we needed to include. It was really tricky and that’s the part I don’t like. I don’t like having to say to people, we can’t include you. That’s why I chickened out and said, “I don’t think I want to do this.” She [Mona] said, “Well, you can put me down as an editor.” She has not done that yet [laughter]. I’m going to blame all the omissions on her—”It was Mona! She’s so mean! She can just cut people out!” I would have had 157! Or 177. [laughter]

J.P.: Did you know all of the poets that are in this book?

S.M.: No.

J.P.: But did you know of their work?

S.M.: Yeah, it’s hard not to. I think there may be one or two who are really new who I didn’t teach. I teach now at UBC. I say to my friends Patrick Lane and Lorna Crozier, “When we were starting out, there were no writing workshops.” I think there was one out at UBC. Earl Birney used to teach creative writing [when he was in the UBC English Department]. But now we’re teaching all these people how to write, all our trade secrets, and they’re all winning prizes, and getting published and it’s hard as you get older. People want the new voices. And it’s like, “What are you doing? Maybe we should just shut up and not be teaching people.” But there are always amazing writers coming along.

J.P.: Poets of the past like Page, Lowther, Livesey, they’re not in this collection.

S.M.: Right. If you die, you don’t get to be in this anthology. If you just had 77 dead women poets in B.C., there’d be a whole other anthology.

J.P.: Do you find that you run into people that are surprised that there are this many women poets in the province?

S.M.: I haven’t had that reaction. But I was really shocked that there were that many. There’s that old saying if you throw a stone…oh no…that’s different. Well, if you throw a stone in any mental hospital, you hit a poet.

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: But that doesn’t apply here. [laughter] All the poets here have pretty good reputations, that’s what’s really astounding. I wonder if it would be the same in Alberta and all the other provinces, if you could come up with 77? Maybe that’s another project for Mona. She could do 77 Manitoba women poets; spend the rest of her life doing this.

J.P.: What do you think this collection says about British Columbia?

S.M.: I don’t think that way. I mean, I don’t know what anything says about anything quite honestly. I read individual poems and lines of poems, and they either affect me or they don’t. I don’t look in the general way. It’s too hard. It’s like being in the forest and trying to see the trees—I suppose I’m trying to use some pathetic analogy. But when there’s that much poetry it becomes overwhelming. I’m on a lot of juries and I find that this is the worst way to read poetry, when you have 100 books of poems because, well, pretty well everything starts kind of blending into one. It’s very hard to come up with something that stands out. So there’s a risk of that when I had ten poems from each poet to read, that how am I going to see what really jumps out at me. There was something quite difficult to do; how to pick the best. So I ended up asking the poets to please list your top four—what you would like to see represent you. Some said they didn’t want to do that, they wanted me to choose, and others did. And then we had some longer poems. I think Anne Cameron has a longer poem. I wanted a balance. I wanted different kinds of poetry, what they call language poetry, which is more sort of conceptual. And I wanted some concrete poetry, Judith Copithorne and a couple of other people. So I wanted to show that there are many different kinds of voices and form being written here. I think poetry’s individual—it’s a collection. It’s overwhelming. I look at the book, I pick it up: It’s such an amazing object. And then I dip into it, but I don’t read it from cover to cover. I read bits. I read bits of poems and sometimes I read them backwards. I may not be the ideal reader [laughter].

J.P.: Do you think there’s anything that can be done to make people more poetry savvy?

S.M.: I think having poets in schools has changed a lot. It’s true that school ruins you for poetry. Well, we were taught the romantics when I was 14, and I was worried about the atom bomb falling on me, we would have ‘Daffodils,’ and I would think, who is this person? ‘Daffodils’ is taught in more countries that are colonies of Britain in places like Africa where nobody’s seen a daffodil, and they still have to memorize that poem. It’s done a lot of damage in the world. [laughter] So you get people learning things or studying things that doesn’t have any bearing on their life. What you need to do in schools is be teaching rap lyrics, or just expose people to poetry and say, “If this appeals to you, great. Go and listen to more of this, or read more of this.” In any anthology, you might find one or two poets you like, and then you go and look for more of their work.

What I always say to people who want to write, “Start with an anthology like this one, read through it, find what appeals to you, and then read more of that. But a lot of it’s not going to appeal to you.” Quite honestly, that’s how poetry works. You can show your best friend your favourite poem and they’ll go, “Oh that’s great.” But they don’t have that same emotional reaction you do because it’s triggering all sorts of things from your life in you. They may show you their favourite poem and you’re… “oh, whatever!” [laughter]. The problem with poetry is that you don’t get the same poem appealing to lots of people. You get the odd poem that does and that’s pretty much a miracle when that happens. There are probably lots of poems in history that have affected people but school is where it starts being ruined because we feel self-conscious, we feel that we don’t get it; it’s too lofty for us. It’s a language we don’t speak. I prefer plain language in poetry. Lew Welch, an American poet says, “Rinse your ear, language is speech.’” I love Tom Wayman’s poetry because he wrote about work and people’s jobs. He’s not in this, of course, he’s not transgendered or a woman.

J.P.: [laughter] Who else is like that?

S.M.: Kate Braid writes poems about her work as a carpenter. So, I like poems that speak directly. I like Lorna Crozier’s poetry a lot. Tons of poems in this anthology. But there’s something for everybody and I think that’s the thing. I tried not to just inflict my taste on the world here. The job as an editor is not just to say that these are my favourite poems. These are the poems that, you know, in this book, you might find something that appeal to you. That was my attitude.

J.P.: Elizabeth Bachinsky is in this collection. In her latest collection she has a transcript of an instant message conversation she had with someone. I asked her if there can be poetry in a Tweet or a Facebook update. And if if that’s the case, anybody can be a poet.

S.M.: Well, there’s poetry in it, but it doesn’t mean everybody’s a poet. I find poetry everywhere. I teach my students about rhyme and repetition. I say, just look around your community. Like, “Be wise, immunize.” There’s signs everywhere that use poetry. Rhyming poetry because it catches your attention. If it said, “Be wise, get your inoculation,” it wouldn’t have the same ring, right?

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: So there is poetry everywhere, which is perhaps why people think it is easy to write. I certainly think there is poetry in Tweets. I just got my first cell phone on Saturday so I’m quite new to this, but I do Twitter. Margaret Atwood told me I had to be on Twitter. After two years, I am just kind of getting it. You get your news through Twitter. You find out that Osama Bin Laden’s dead before anybody else does.

J.P.: Right.

S.M.: He’s allegedly dead.

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: And there are some wonderful mistakes and malapropisms that can be like poetry. One of my guests asked for an ensuite bath, and it came out ‘Einstein’s bath.’

BOTH: [laughter]

Susan Musgrave decompresses

S.M.: Oh yes, we definitely have a room with Einstein’s bath! So who knows what poetry is? I think there’s a quotation that says something like, “The world is made so very much poetry but not so very many poets.” It’s hard not to be elitist about it. I think it’s great that anybody writes whatever they want to write if it makes them feel better. But it’s difficult when people come to me saying, “Why am I not getting this published?” I can tell by the first two lines why they’re not. If you try to explain to them, “Have you read any contemporary poetry?”, they’ll say, “‘Well no, I don’t want to be influenced.” I hear that a lot. Well, you need to be influenced because if you’re not influenced you don’t know the market, you don’t know what’s trendy. Gerard Manley Hopkins: if you wrote like him now, you wouldn’t get published. So, that’s the problem. That was a phase in time where people wrote poetry that illuminated…

My theory is that you need beautiful language with ugly subject matter so there’s a friction. The romantics had beautiful subject matter with beautiful language, like ‘Ode to the Nightingale,’ and we just don’t go for that. We know that’s sort of being fairly, you know, head in the clouds. But you can write about something that’s like you know, rape and murder and war, but your language is elevating it. What is it Nietzsche says? “Everything we call higher culture is a spiritualization of cruelty.” I don’t like the word ‘higher culture.’ I think everything we call art could be seen as a spiritualization of cruelty. So if you can make cruelty and unpleasantness palatable to people through poetry, or make them feel something about a situation that they may have become immune to, I mean, we hear so much about war and violence, who feels anything? We go: Yeah, another 50 people dead in Syria today. Oh well… Gotta take my bread out of the oven.

J.P.: Do you want to check your bread? And we can pause.

S.M.: 16, 15, 14… I just need to take the lids off and let it cook for another 20 minutes.

J.P.: We can pause.

S.M.: Sure. Let’s just pause. I’m just going to put the phone down.

J.P.: Sure, sure.

[rattling of pans; timer beeping]

S.M.: There! Okay!

J.P.: I once interviewed Robert Bateman and he was painting while we were chatting.

S.M.: Did you get the sound effects? [laughter] The little beeper going off, and yeah. It’s amazing bread. The recipe is from a bakery in San Francisco; the method: Tartine Bakery. You don’t knead it. You turn it. So, for four hours, every half hour, you have to get up and turn this bread. And it’s great when I’m writing or teaching because it makes me get up. Otherwise I would just be sedentary.

J.P.: I read somewhere that someone had read a poem of yours and kept it with them for six months because they were so moved by it. Yet you told Shelagh Rogers in an interview recently that process excites you rather than the final product. You obviously have a different relationship to your writing than readers do.

S.M.: Well, I hope so. I mean, if I was absolutely moved by all my poems, I’d be a quivering mass of protoplasm [laughter] weeping over my poems. I think you’re struggling with lines and where to break the line and you get the first draft and hope to retain whatever the emotional thing going on there was, but then you start rewriting. The rewriting is where the craft enters it. And so you become a little bit detached. I can read some older poems and go back to the place I was in my head when I wrote them…but the poems I wrote for my daughter were still really raw. When I read them I have to pinch myself. Like when I’m at the dentist I don’t want to show that I’m terrified, so I pinch myself. I come out of the dentist with these marks, like claw-marks all over my arms.

I read a couple of the poems for my daughter when I was in London and did that to stop crying. So they’re still pretty raw. I suspect that that will diminish, but I’m afraid to read them really because they have that effect on me still. But they’re a year old. The situation is one of her being on the street so I’m still always worried about her. It doesn’t go away. And I know that there are an awful lot of people who are experiencing the same thing which is, I think, what made me decide to write the poems. People come up afterwards and sort of whisper their story about their daughter or their son and it’s so much pain in people that they’re ashamed. They don’t know who to talk to about it. And I want people to know they’re not alone.

That’s what poetry does too, it makes me feel not so alone when I read a poem that speaks to me in some way. And that makes me say, “Oh, other people feel the same grief and the same loss.” And so, I think it’s all about connecting, writing poetry. But I kind of like it when the emotion dissipates, if the poem has a life of its own. Poets talk about that. It’s born and then you’re just the person giving birth to it. I mean it sounds really hokey, just like a child. It goes out into the world and has its own life and other people, as you say, carry it around and it means a lot to them. There are poems I’ve carried around with me. There are some on the wall in front of me that really mean a lot, and if I were to meet the poet, it doesn’t really matter. It’s the poem that matters.

J.P.: Do you find solace or wisdom in what you’ve written yourself?

S.M.: Sometimes I find wisdom. It certainly seems beyond me. Poems always seem to know more than I do and to be wiser than I am, as far as I can see. That’s also what’s magical about writing. Where do these things come from? Because I don’t feel like I’m all that. I’m definitely wiser than I was, but I don’t feel like an oracle, that people come and sit at my feet and expect me to say wise things. I don’t feel like that, I feel like just a lost, I don’t know…I dream about being lost…I dreamt I was lost on the BC Ferry and couldn’t find my cabin…My life is a series of being lost. Everybody I know who’s in the arts and maybe every human being at some level feels unworthy. And where does that come from?

J.P.: I think that’s what people relate to.

S.M.: But people are afraid to say it. You’re not supposed to say it. You’re supposed to say, “Oh, everything’s great! I feel wonderful! I’m on top of the world!” I look at people like that and then I’m envious of them. How can they be so happy? But then, it turns out, scratch the surface…

J.P.: And they’re lying to you.

S.M.: They are lying. They’re lying because people will like you better if you lie. Who wants to really hear the truth about when you say, “How are you?” I love the Irish: “It’s never better.” I say that all the time now. “How are you doing” “Never better!”

BOTH: [laughter]

S.M.: The ultimate lie! I saw this wonderful psychiatrist who I call Shabby the Rasby, who’s a Buddhist and he’s Persian. He says, “Well, Susan, just small talk when people say, ‘How’s your day going so far?”’ But, like, my dad just died, and you know my husband’s just gone to prison. My daughter’s just got addicted. How can I just say, “Great!” [laughter] If you tell them the truth, people just look stunned. So I haven’t mastered small talk. I’m better at it, but I still take those questions really seriously. “How are you?”

J.P.: laughter] But people do sit at your feet and view you as some sort of oracle, don’t they?

S.M.: Right now I’m looking down and there’s cat hair all over the carpet. My cat certainly does. It’s nice in this community because Wendy Riley and me are sort of the older women. Like, we’re in our Sixties. And it’s not a sort of ageist community, people of all ages mix here. And so people do come, not for advice, but just to come and talk. I don’t think they’re looking for anything. They don’t come to me as a poet, they come to me as a person, which again, is why I like it here. I don’t know how Margaret Atwood feels, but when you become an icon—that’s something made of wood, isn’t it? It’s not living anymore. David Phillips, who had Copper Beech House before I did said, “Masset forces you to be honest.” There’s not a lot of pretence here. It’s pretty real. You need other people in order to survive because the weather gets stormy, and it’s small. Nine hundred people. Another nine hundred in the village of Old Masset. So, I don’t think they come and sit at my feet at all. They come and drink my wine [laughs]. I tend to order cases of wine because my brother in Victoria knows about good wine. I have good wine. The liquor store here, you can just buy Yellow Tail, that’s about it.

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: So they come and sit at my table and drink wine. Last night, we processed all the sea spinach… I volunteer at the thrift shop here, that’s a big deal in Masset. There’s nowhere else to donate anything, so it’s one of the best thrift shops in the world. A friend of mine across the road, who’s just been hired as an archaeologist, donated her Blackberry by mistake, or her iPad thing. It was in an basket full of clothes. So we found it, and she came over to get it and I was processing sea spinach. So we ended up eating all the sea spinach and drinking a bottle of wine. That’s kind of how life is here. It unfolds, and I like that. People drop in a lot. They don’t do that in the city because you don’t dare, right?

J.P.: Are there used bookstores in Masset?

S.M.: Nope. Just the thrift shop. And everything’s fifty cents. I was at Value Village last week in Victoria and I was appalled that used books were $4.95. I’m going, “What?’” In Masset we pay less and they’re really good books because people up here read like crazy. Just so many readers. I think there’s may be a bookstore in Charlotte, on Queen Charlotte. There is, Isabel Creek, it’s a health food store downstairs and a bookstore upstairs.

J.P.: When you were starting out as a writer, you got to know people like Al Purdy. What did that mean to you as a writer?

S.M.: No, I didn’t many meet writers. I didn’t really know what I was doing. When I was about 18, I’d read The White Goddess, because the man I was living with, Sean Virgo, was a great fan of Robert Graves. I think he’d gone back to his wife and I had to do something in Europe, and that was my first trip to Europe, so I went to Mallorca. And I went to lost luggage because I was lost again and a young man called Rodrigo—he was a stamp collector and offered to be my guide of the island, and he drove me to Deyá and I took a pensionné, which was like a dollar a day. And I just went to Robert Graves’ house and knocked on the door! [laughs] I can’t believe I did that! And he sort of took me under his wing for about a week while I was there and that was interesting. And I met Al Purdy in Mexico.

I was down there seeing as my house had burned down up here. So I sort of fled to Mexico and met another poet in Mexico City. And then we went up to Mérida and met Al [Purdy] and Eurithe. So I knew them as people, and as people first rather than writers. Al loved talking about poetry, he was bored talking about anything else. But we had some great adventures down in Mexico together and then I stayed in touch with him up here. The poets I liked best are the people I know as friends. And I do like their work, but they don’t sort of sit down and talk to me about my poetry or anything. I was quite a young poet and I think Al didn’t really take women poets very seriously. He’d edited a book called Fifteen Winds, it had two female poets, and forty-nine male. And at one point, just before he died, he gave me this huge anthology called 500 Women Poets, like from 10 B.C. to the present day. And he said, ‘Here.’ And I think it was his way of saying he accepted me as a poet. A poetess rather.

J.P.: A poetess.

S.M.: He was pretty old school. It was sweet. And the fact that he would even talk to me about poetry was, I suppose, a compliment.

J.P.: Now reflecting on this life and career of yours. You know, there have been good times, great critical success over the years, and there’s some less than pleasant times. Are there regrets at all?

S.M.: About what?

J.P.: About life in general, about the career, or anything like that.

S.M.: Well, like regretting being born? That kind of thing? Because, yeah.

J.P.: Or the choices that you made…

S.M.: No. What’s the point? School put me off being interested in everything. I thought everything was boring. Learning was boring because I was at school. And it wasn’t till about forty that I thought, “I want to learn something every day.” And if I learned something, that makes life not so depressing. And then I’m interested in linguistics; I’m interested in criminology. I’m interested in all these things, and what if I’d gone to university and, you know, maybe studied those things. Even archaeology. Lots of things. I just didn’t. And maybe I wasn’t meant to. I’m pretty fatalistic about things. I don’t regret my life. I wish I had not been discouraged at school. Like I used to win medals for coming first in elementary school. You know three times, top of my class. And then I got bored. So my marks dropped, and then I dropped out and that’s the story of a lot of people’s lives actually. Patrick Lane just got an honorary doctorate in Kelowna this weekend and he said, “Goodbye the high school diploma I didn’t get!”

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: I wish somebody would give me an honorary doctorate so I could be Dr. Musgrave. I could say to my mum, “See! It didn’t matter that I didn’t finish grade twelve [laughter] Because there’s still that parental: “Finish grade twelve and the world is your oyster,” as my dad used to say. I’m allergic to oysters though.

J.P.: Are you?

S.M.: Well, I think I am.

J.P.: In terms of your view on education, id your children have the same experience that you did?

S.M.: Yeah, it turns out that people unfortunately do follow their parents—like Charlotte, I think, went and finished grade twelve on her own, when she was working at a little coffee shop in Sydney. She got everything but one credit. Sophie was sort of involved in racial tension things so she would always side with the Native people, and then she got kicked out for intimidating a girl. You know, long story, but I just couldn’t send her back. I was just so pissed off at the school system. I was not one to force my kids to go to school because I knew how damaging it had been to me.

I’m told it’s a different world now and they need this and they need that, unless they’re musical or artistic in some way and can make it, you pretty well have to do something. I see my brother has both his kids at university and that’s because every day he made them get up, and he made them go to school, and they did. But I would just sort of give up and think, “Ugh. Why would I be sending them to this place?” And it’s really hard for me to be positive to anybody about high school and middle school. I try to, like I see people’s parents. But I see kids suffering. There’s an amazing book by Grace Llewellyn called A Teenage Liberation Handbook: How to Quit School, and Get a Real Life, and an Education. She talks about how education is so important, but schooling is absolutely not. And this school system began in Prussia and it was to make factory workers, and people who could work nine to five. Not for people who want to think outside that kind of life. And now especially, you can’t just get a job and work at that one job until you die. Now people don’t do that. They change careers all the time.

Teachers are part of the whole thing. They start out being really positive, like prison guards, and then they get jaded because they’re up against so much that they can’t do. There’s a system there in place. And maybe it’s changed. Maybe it’s not quite as bad as when I was at school. At least poetry isn’t taught as punishment as it was when I was at school. We had to memorize poems for punishment, for detention.

J.P.: And now what do you when you’re the teacher?

S.M.: I rail against the system. I tell them, if you want to write, I don’t know what you’re doing in university. Well, I know what they’re doing, they’re getting another degree so they can get paid more. And some of them want to learn to write, I shouldn’t malign everybody. Everybody I’ve taught poetry to at UBC, they’re really great, and they’re good writers. But I don’t know why they want an MFA? I guess I shouldn’t be saying that as somebody who teaches in the program.

J.P.: [laughter]

S.M.: I think more people should have MFAs! The real writers are going to write no matter what, and they do. I see my job as helping people overcome their fear of poetry and, not only that, but liking it. One of my best reviews was a student who said, “Susan Musgrave has made me hate poetry a little less.” So, if I can do that, I think I’ve succeeded. What I get over and over again is, “Oh, thank you for taking away my fear of poetry and making me actually love it, and be a better reader of it.” But I have students who already have two Ph.Ds, who’ve published 13 books, this kind of thing. So one wonders what it is they have to learn from me, probably nothing. But they get something from the whole group; you know, it’s pretty stimulating. And to have feedback for your work is really excellent, too, because that’s hard to find in the community. People who will be honest and also incredibly sensitive.

I’m amazed at the kind of feedback these kids give each other. So that’s what you do get in this program at UBC and generally in workshops. But these people have really learned how to be good critics and editors and they’ve learned to be even better in the program. I love it actually, but I still feel that within the system—those of us who teach in the optional residency–we’re still rebels you know. There’s Brian Brett, who teaches in the program, Terry Glavin, Wayne Grady, a bunch of us who, not all of us have degrees. In fact, a lot of us don’t. We were hired because we were kind of hands-on writers. And who worked in the field… [laughs] So…

J.P.: I really appreciate your time. It’s been such a pleasure talking to you.

S.M.: You too! This has been great. You ask great questions. I’m usually quite reticent, as you know [laughter]. My bread’s about to come out of the oven and I’ve got to go to the thrift shop…

AFTERWORD