Interview with Bud Osborn

May 08th, 2014

Bud Osborn’s voice changed lives in DTES

INTERVIEW WITH BUD OSBORNE (1999) BY BC BOOKWORLD

BW: When did you start writing?

OSBORN: In high school. I had a lot of trouble growing up, many kinds of destructive situations. I began writing on my own. Later on I found out there were poets whose lives were as messed up as mine. They seemed to understand me better than anyone in my life.

BW: Who?

OSBORN: [Arthur] Rimbaud, [Charles] Baudelaire. And I had an anthology of Beat poets. [Allen] Ginsberg’s Howl and Kaddish. Reading poems helped me get through another hour, another night, another day. I had been very suicidal until then.

BW: How close to death were you?

OSBORN: The first time I was laying, bleeding to death in a park. It was late at night, three or four in the morning, in Ohio. I was very drunk. I had fallen on my head and burst an artery. A police car went by and never even noticed me laying there. I was in the shadows, in the mud, and the blood was just pumping out of an artery in the back of my head. I figured, ‘Well, this is it.’ I remember the grass being wet, and the earth.

All of a sudden, this white Cadillac pulled to the curb, and these strong arms were lifting me to my feet. I was bleeding and muddy and drunk and they put me in this clean back seat and pressed a towel to my head and took me to the hospital. To this day I have no idea who those people were.

BW: Have there been other times when you were ‘saved’?

OSBORN: Yeah. Several.

BW: What happened to turn things around?

OSBORN: I was written off by psychologists, by cops, by judges. I was even written off by myself. I thought, “I’m not going to have a life.” It seemed foreclosed. And then something new happened in my life. One day I emerged, 45 years old, broke, homeless, in a detox centre, with nothing, and I thought, “Well, what am I going to do from here?” I decided I didn’t want to be so self-absorbed. Since then I’ve been able to contribute, to work with other people, and to passionately advocate for others. I’m still kind of stunned, going from one place to another.

BW: Where did you find the will to start working for other people?

OSBORN: I’ve thought about that. It must be somewhere in my background. My uncle organized unions in Toledo where I grew up. I remember him as being a very intense man. He fought the U.S. Army in the streets of Ohio. Strikers were killed. And my grandfather had been a coal miner. He was working in a coal mine in southern Illinois and there was a strike. Scabs were brought in from Chicago, and the miners surrounded them with rifles and opened fire. The scabs gave up, they surrendered, and the coal miners murdered 17 of them. When the coal miners were brought to trial, they were all acquitted. It would have been impossible to convict a miner in southern Illinois for the murder of a Scab.

Growing up, every kind of curse word was common currency except for the word Scab. If you said that, you were saying something really negative about somebody. That was the worst thing you could call somebody, the worst thing you could be.

BW: What about your mother and father?

OSBORN: My mother was a manic depressive and in one of her later manic phases she decided to run for president of the United States – seriously. She happened to be in a psych ward at the time. She had been in the U.S. Army. She would always end up on this ward with Vietnam vets. So one day she announced that she was going to run, and called a press conference. My mother said she was going to run on behalf of all the mental patients, all the alcoholics, the addicts, all the poor people, the Vietnam vets that were so stressed out and troubled.

BW: All the people who were right at the bottom.

OSBORN: Yes, exactly. An irony in the Downtown Eastside is that there are two hotels within a block of each other on East Hastings Street. One is the Walton; the other is the Patricia. Those are the first names of my parents; Walton and Patricia. I think about that sometimes. It’s as if there’s a family connection in terms of trying to defend people who are being assaulted down there.

BW: Do you believe in destiny? Do you have a faith?

OSBORN: I don’t know how to define theology very much, but I realize now that I don’t have the last word. Human beings don’t. We would like to, but it isn’t that way. Other factors are involved. There’s another hand involved, otherwise I wouldn’t be here. The hope of bringing possibilities out of impossibilities, that sustains me. And it sustains some of the people that I’ve met who have said, “Don’t stop. Whatever you’re doing now, just don’t stop. Don’t stop fighting.”

For instance, there has been an intense and relentless police attack on the 100-block Hastings area without taking into consideration that there are other ways to solve the problems around illicit drug use. Those are the sort of things that concern me on a day-to-day basis. That’s why it’s really exciting for me to work with musicians. It’s a way to expand the discussions beyond grinding political meetings or making speeches.

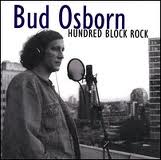

BW: Did you actually record your CD on the roof of the tall building, or is that just a promo thing?

OSBORN: No, we recorded in a studio on the roof of a building.

BW: It’s ironic to be making music on a skyscraper about life down on the street.

OSBORN: What can I say? I guess music can be celestial and down-to-earth at the same time.

BW: What happens if you get hugely successful and you wind up with tons of dough?

OSBORN: I’d buy Woodwards and develop it for the needs of the people of the Downtown Eastside.

May 07th, 2014

Vancouver poet and Downtown Eastside activist Bud Osborn, the unofficial archivist of Canada’s poorest neighbourhood and its most eloquent and forceful author and spokesman, has died after recently being diagnosed with a heart problem. He was hospitalized for five weeks, came home for one day, and died, according to Ann Livingston, a former partner and co-founder of VANDU (Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users). Tweeted tributes began early on May 7, 2014 when the news first aired on CBC Radio.

NDP MP for Vancouver East, Libby Davies, a longtime friend, says Osborn’s passing is an enormous loss to the community and that he was a hero to the people of the DTES and the City of Vancouver overall. She adds that Bud Osborn understood harm reduction and safe injection sites as important health measures and a fundamental human right. “I credit him with being able to change the way people perceive drug users,” Davies says.

Osborn’s poetry worked in tandem with his activism for people living on the street and poverty issues. “His words captured the raw horror of being abandoned, poor, cold and lonely,” says Livingston. His first publisher, Brian Kaufman of Anvil Press, recalls: “In 1994, Bud delivered his typewritten manuscript, Lonesome Monsters, to the Anvil offices on the second floor of the Lee Building at Main and Broadway. And what I saw in Bud’s work then was the same thing I see now when I open one of his books: raw, brave, human, unadorned depictions of people caught in the meat-grinder life of poverty, homelessness, addiction, and violence. He gave voice to the many that could not put it down in words, to the many who are never listened to. The epigraph he gave me for the book was this: ‘the primary intention of my writing has been fidelity to my experience and those of the people about whom I write.’ And in that, he never wavered.” A chapbook by Bud Osborn called Keys to the Kingdom (Get To The Point) received the City of Vancouver Book Award.

Bud Osborn was born in Battle Creek, Michigan and raised in Toledo, Ohio. His father, a reporter for the Toledo Blade, was a shot-down bomber pilot and former prisoner of war. He received his father’s exact name, Walton Homer Osborn. His father committed suicide in jail, as a traumatized alcoholic, when Bud Osborn was three. Osborn himself tried to commit suicide with 200 Aspirins when he was 15. “Amid our peregrinations through poverty neighborhoods, I was so afraid of my name that when a tough alley urchin gang leader in another new location asked my name, I said my name was Raymond or something, but this raggedy kid replied, ‘No, it isn’t. It’s Bud!’ And I have insisted on being called ‘Bud’ ever since.” Osborn began to consider himself as a perpetual bud on a tree, never to bloom or come to life. He briefly attended Ohio Northern University and took a job with VISTA in Harlem as a counselor. He became a drug addict, married and had a son. His family accompanied him to Toronto, but then his wife and son left him to go to Oregon. He lived on the mean streets of Toronto, Toledo and New York until he moved to the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver where he eventually entered Detox. “I stopped running and tried to face myself,” he says.

Osborn’s former life as a lost soul on the mean streets of Vancouver has been dramatized in an award-winning film called Keys to Kingdoms, made by Nathaniel Geary. A former addict who was ‘seven years clean’, Osborn became a board member of the Vancouver/Richmond Health Board, the Carnegie Centre Association Board and VANDU (Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users). In the process he began working closely with MP Libby Davies and advocating for the introduction of free injection sites. “I realize there are not many people who can advocate from the bottom, who have lived at the bottom,” he said. As a City Council candidate for COPE, Osborn became a fierce adversary of Mayor Philip Owen and met with federal Health Minister Allan Rock. He did remarkably well at the polls for someone who could have been dismissed as a former alcholic and drug addict. Although Osborn didn’t win election, Mayor Owen reversed his stance and accepted most of the policies that Osborn and Davies had been advocating. A reunion with his son ensued after 30 years of separation. Osborn has described it as “the single most powerful experience of my life.”

In his poetry Osborn has portrayed the ‘scorned and scapegoated’ of his neighborhood as brave souls fighting for their dignity. His collection of poetry from Arsenal Pulp and a CD of songs produced by Alan Twigg, both called Hundred Block Rock, were released to coincide with his performance at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival with bassist Wendy Atkinson and guitarist David Lester. “The title Hundred Block Rock refers to the 100 block of East Hastings,” he said, “It’s the epicentre of several pandemics. Probably the only comparable conditions are some of the worst places in the so-called Third World.”

In his second poetry collection, Oppenheimer Park (1998), with prints by Richard Tetrault, Osborn offers a plea for compassion in ‘A Thousand Crosses for Oppenheimer Park’. The long poem was spoken at a memorial service to mourn and protest the needless deaths by drug overdose of more than one thousand residents of Vancouver’s downtown eastside. “Any one of these thousand crosses could easily represent my own death,” he says. Oppenheimer Park was privately printed for subscribers. His first book was Lonesome Monsters (Anvil 1995). See Interview.

For more than twenty years Bud Osborn was also an unofficial archivist of the Downtown Eastside [DTES], Canada’s poorest neighborhood.

“We have become a community of prophets,” he wrote, “rebuking the system and speaking hope and possibility into situations of apparent impossibility.”

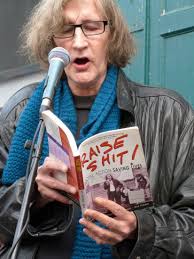

Along with Donald MacPherson, the City of Vancouver’s Drug Policy Coordinator since 2000, and UVic academic Susan Boyd—who lost her sister Diana to a drug overdose—Osborn, who ran for City Council in 1999, has documented the social justice movement in the DTES that culminated in the opening of North America’s first supervised drug injection site.

As a landmark celebration of collective activism and resistance, Raise Shit! Social Action Saving Lives (Fernwood 2009) is a sophisticated history of despair and courage, commitment and hope. It is also an important contribution to the serious literature on drug prohibition and inspiring story of how marginalized citizens have refused to let their friends’ deaths be rendered invisible.

“Our story is unique,” wrote the trio of authors. “It is told from the vantage point of drug users, those most affected by drug policy.”

The DTES made headlines around the world in 1977 when a public health emergency was declared in response to the growing rates of HIV, hepatitis C and overdose deaths among drug users in the area. At its outset, this montage of photos, news stories, Osborn poems, MP Libby Davies letters, journal entries and records of early Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users [VANDU] meetings does not fail to note: “From the early 1980s, poor women, many Aboriginal, associated with the DTES, went missing. Twenty years passed before one man was charged with the murders of 26 of the missing women; however, later he was convicted of six counts of second degree murder. The investigation is ongoing, and poor women remain vulnerable to male violence.”

[For other authors pertaining to the Downtown Eastsideprior to 2011, see abcbookworld entries for Atkin, John; Ballantyne, Bob; Baxter, Sheila; Brodie, Steve; Cameron, Sandy; Cameron, Stevie; Campbell, Bart; Canning-Dew, Jo-Ann; Clarkes, Lincoln; Craig, Wallace Gilby; Cran, Brad; Daniel, Barb; Douglas, Stan; Fetherling, George; Gadd, Maxine; Gilbert, Lara; Greene, Trevor; Herron, Noel; Itter, Carole; Knight, Rolf; Lukyn, Justin; Mac, Carrie; Maté, Gabor; Murakami, Sachiko; Murphy, Lorraine; Reeve, Phyllis; Robertson, Leslie A.; Robinson, Eden; Roddan, Andrew; Swanson, Jean; Taylor, Paul; Tetrault, Richard; Vries, Maggie de; With, Cathleen.]

BOOKS BY BUD OSBORN

Lonesome Monsters (Anvil 1995). $10.95 1-895636-08-6.

Oppenheimer Park (1998), with prints by Richard Tetrault. 0-9683337-0-2.

Keys to the Kingdom (Vancouver: Get to the Point, 1998).

Hundred Block Rock (Arsenal Pulp).

Signs of the Times (Anvil Press, Signs of the Times, 2005). with prints by Richard Tetrault.

Raise Shit! Social Action Saving Lives (Fernwood 2009), with Donald MacPherson and Susan Boyd. 978-1-5526-6327-1

Leave a Reply