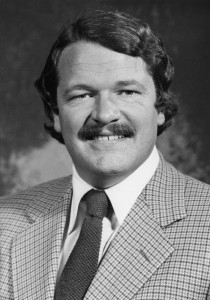

#185 Samuel Bawlf

September 08th, 2016

LOCATION: Sam’s Deli, in the Belmont Building, 805 Government Street, Victoria

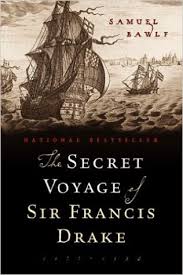

This deli was founded by Sam Bawlf in 1972, the same year he became the youngest-ever alderman on Victoria’s City Council. Born in Winnipeg on June 7, 1944, Samuel Bawlf of Saltspring Island was a former Social Credit cabinet minister who later published a bestselling biography of Francis Drake in 2003. It purported to prove that Francis Drake was the first European mariner to reach the waters of present-day British Columbia (near present-day Comox). Although his arguments were debunked by other Drake experts, this did not prevent the book from gaining traction in a society that largely preferred the ‘discoverer’ of British Columbia to be British.

Robert Samuel Bawlf of Vesuvius Bay on Saltspring Island died of cancer on August 20, 2016, at age 72, after being admitted to Lady Minto Hospital on Saltspring Island about a week-and-a-half prior to his death, having had surgery for bladder and prostate cancer two years before. He was unable to complete an anticipated follow-up book to his B.C. bestseller with sales estimated in the range of 20,000 copies.

Raised in Vancouver, Bawlf studied urban planning at UBC. In his twenties he became active in the restoration of old buildings in Victoria’s Bastion Square. He was a Social Credit MLA from 1975 to 1979 for the constituency of Victoria, earning a place in Premier Bill Bennett’s cabinet as the Minister of Heritage and Conservation and overseeing the province’s first heritage conservation act. His older brother Nicholas was a celebrated architect who died in 2012. The brothers were simultaneously honoured by Heritage Canada in 2007. Their great-grandfather Nicholas Bawlf was a pioneer of western Canada’s grain industry. Bawlf’s papers from his Francis Drake research have been donated to the University of Victoria Library.

Raised in Vancouver, Bawlf studied urban planning at UBC. In his twenties he became active in the restoration of old buildings in Victoria’s Bastion Square. He was a Social Credit MLA from 1975 to 1979 for the constituency of Victoria, earning a place in Premier Bill Bennett’s cabinet as the Minister of Heritage and Conservation and overseeing the province’s first heritage conservation act. His older brother Nicholas was a celebrated architect who died in 2012. The brothers were simultaneously honoured by Heritage Canada in 2007. Their great-grandfather Nicholas Bawlf was a pioneer of western Canada’s grain industry. Bawlf’s papers from his Francis Drake research have been donated to the University of Victoria Library.

*

Certainly the deadly privateer Sir Francis Drake did give the western coastline of the U.S. its first, widely recognized European-based name—Nova Albion, essentially New England—but historians have agreed to disagree about whether or not Drake might have sailed above the 49th parallel prior to any other European.

Details of Drake’s heroic 1577–1580 global voyage to “the very end of the world from us” were mainly recorded by the Cambridge-educated cleric Francis Fletcher who kept a journal on board the Golden Hinde. “Whether Drake reached the coast as far north as the Strait of Juan de Fuca,” according to Derek Hayes, author of Historical Atlas of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest, “is likely to remain a puzzle.”

The site of Drake’s Harbour, called Portus Nova Albion, where Drake took possession of the coast in the name of the Queen of England, is sometimes ascribed to Whale Cove on the Oregon coast or various bays in California.

In 2003, Samuel Bawlf transformed and expanded his self-published Ph.D. thesis on Sir Francis Drake for a controversial biography that alleges Drake was indeed the first European to reach British Columbia in 1579, but there is no conclusive evidence.

In 2003, Samuel Bawlf transformed and expanded his self-published Ph.D. thesis on Sir Francis Drake for a controversial biography that alleges Drake was indeed the first European to reach British Columbia in 1579, but there is no conclusive evidence.

Despite the packaging of Bawlf’s The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake as a revelation, he was not the first historian to propose the Drake-Came-First theory. In 1927, the prolific social reformer A.M. Stephen of Vancouver published his first novel, The Kingdom of the Sun, about a gentleman adventurer named Richard Anson who sailed aboard Drake’s Golden Hinde, only to be cast away among the Haida and fall in love with a Haida princess.

The eldest of twelve brothers, Francis Drake was born in Tavistock, Devon, around 1542. The Drake family had lost property when King Henry VIII founded the Church of England in defiance of Rome. Drake was sent to live with his seafaring kin, the Hawkins family. Leaving Plymouth in 1562, Drake likely accompanied John Hawkins down the Guinea coast to acquire slaves from present-day Sierra Leone. As a Caribbean slave trader in 1568, Drake was at the helm of Judith, two days after entering the principal Mexican port of San Juan d’ Ulúa, when Hawkins’ out-manned flotilla was attacked by the Spanish with terrifying results. Drake fled the harbor, leaving hundreds of desperate English sailors stranded. “The Judith forsooke us in our great myserie,” said one of Hawkins’ men. The romantic ethic of “one for all and all for one” was not for Drake. He was a charming, self-serving man, loathed by many in London and around the world.

The clash with Spain gained Drake his lifelong right to function as a privateer, in essence, a legalized pirate. Drake quickly became famous for his looting of Spanish galleons. He made profitable voyages in 1570 and 1571, trading slaves in the West Indies, then commanded two ships in 1572 to specifically attack the Spanish. Spanish mothers took to frightening their children into good behavior with tales of “El Draque,” the Dragon. Drake was known as a harsh taskmaster. When one of his brothers died at sea, he proceeded to have the body dissected to find the cause of his death. Impressed by his daring, Queen Elizabeth sent him on a secret mission to plunder Spanish settlements on the Pacific Coast of the New World in 1577.

Drake departed on December 13, 1577 and quickly reached Morocco, losing a boy overboard en route from the supply ship Swan, the first of his many casualties. Drake got lucky in early February when he commandeered a Portuguese ship off the Cape Verde Islands, kidnapping its veteran captain Nuño da Silva who had sailed to Brazil many times since his boyhood. In the process, Drake acquired charts for his Atlantic voyage and soundings for the South American coast as far south as Rio de la Plata. He would employ a similar tactic, with equal success, when he reached the Pacific. Drake crossed the equator on February 17, 1578. In South America they met Indians who never cut their hair, knitting it with ostrich feathers to form a quiver for their arrows. Accusing the troublesome investor Thomas Doughty of treachery, Drake had his adversary executed by ax on July 2, 1578. For food, the crew slaughtered sea lions and penguins. They found the bones of a Spanish mutineer named Gaspar Quesada killed by Magellan in 1522. With his crew afflicted by scurvy and cold temperatures, Drake discovered that a stew of mussels and seaweed could be restorative.

Upon entering the perilous Strait of Magellan, Drake changed the name of his heavily armed flagship from the Pelican to the Golden Hinde. The land south of the strait was called Tierra del Fuego (land of fires) because Indians had lit fires as Magellan had sailed past. On one day in August, Drake’s remaining men slaughtered 3,000 penguins, enough food to last 40 days. After only 16 days battling the currents and the foul weather, they reached the Pacific on September 6, 1578. This was new territory for England. Of the five ships sent, two had already been abandoned before reaching the southern tip of the South American continent. Of the remaining three ships, one was destroyed by violent storms and another sailed back to England. Drake was blown far south but travelled back up the coast. Beset by storms, his crew eventually set sail for the Kingdom of Peru with 80 men and boys, sailing 1,200 miles without stopping. On the island of Mocha, at 38º south, initially friendly Indians attacked their landing party, killing several men with a flurry of arrows. Fletcher recorded in his journal that no one escaped being hit. “Drake was hit twice, one penetrating his face under his right eye and another creasing his scalp.” One crewman was punctured by 21 arrows.

The Spanish were aghast that Drake had become the first English sea captain to replicate Magellan’s path. Their build-up of ports from modern-day California to Chile had been accomplished primarily via overland routes through Panama. Their relatively undefended Pacific ports and shipping made for easy pickings. Drake went to work sacking towns and attacking ships to acquire maps and provisions. During his piratical triumphs, Drake took aboard a black slave as his concubine. Maria, as she was named, was “gotten with child between the captain and his men pirates” and she was to be marooned on an Indonesian island to have the child, along with two black slaves for company.

Drake headed north; a few say as far as today’s U.S./Canada border. He named this uncharted coastal realm New Albion. According to memoirs of the voyage, this name was given “for two causes: the one in respect of the white bancks and cliffes, which lie toward the sea: the other that it might haue some affinity, euen in name also, with our owne country, which was sometimes so called.”

Unable to find a passage home via the imagined Strait of Anian, Drake headed westward across the Pacific, through the islands of Indonesia and finally around the Cape of Good Hope at the bottom of Africa. Drake made it back to England by September of 1580, bearing an enormous cache of spices and Spanish booty. Queen Elizabeth knighted Drake aboard the Golden Hinde for his efforts. Drake was the first sea captain to fully circumnavigate the world. Magellan had died en route, and his crew had completed the voyage.

Naval charts were precious and kept secret during the Elizabethan era. This was especially so with Drake’s round-the-world trip. His charts and rough maps could not be publicized for fear of Spanish competition and reprisals. The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake was eventually published by Drake’s nephew, also named Francis Drake, in 1628. Published in 2003, Samuel Bawlf’s Sir Francis Drake and his Secret Voyage 1577-1580 outlines why Drake’s voyage up the “backside of Canada” has long remained mysterious and controversial.

Bawlf writes, “In time, Drake began giving hand-drawn maps depicting his route around the world to important friends. In an early rendition, drawn with pen and ink on the world map of Abraham Ortelius, his route extended northward along the coast of North America to latitude 57º—the latitude of Southern Alaska—before returning south and homeward via the East Indies. Then, with the help of a young Flemish artist named Jodocus Hondius, Drake produced several more maps. On these maps his track northward terminated at a lower latitude, where an inscription read ‘turned back on account of the ice,’ and then returned southward to a place called Nova Albion.”

Although a bestseller, Samuel Bawlf’s favourable portrait of Drake has proved to be a source of consternation for serious Drake scholars because it crafts some conjectures into implied truths.

Testimony that Drake had ventured up the Pacific Coast, past California, was gained by the Spanish by March 24, 1584 when John Drake, Drake’s brother, was formally brought before the Inquisition during his captivity in Argentina. John Drake was interrogated again in Lima, Peru on January 8, 9 and 10, 1587. The gist of John Drake’s confessions about his role in Francis Drake’s secret voyage, reliable or not, was published by Antonio de Herrera, the Historian General of New Spain, in 1606. John Drake’s testimony is stored in the Spanish archives of Seville.

Emerging Protestant attitudes stressed individual achievement—in essence, if you could make money, this meant God favoured you. Drake won God’s favour as a privateer. He was the harbinger of a new age, essentially a self-made man. The once lowly seaman became mayor of Plymouth in 1581 and a Member of Parliament in 1584. In 1585 Drake led a large fleet to the Caribbean to terrorize the ports of Spanish America. Sir Francis Drake’s plundering was so successful in the Caribbean that he ruined Spanish credit, nearly breaking the Bank of Venice to which Spain was heavily indebted.

Drake gained permanent heroic status in the annals of English history by playing a major role in the defeat of the once all-powerful Spanish Armada in 1588. But the Spanish navy wasn’t completely destroyed. Four Spanish ships made a daring raid on Penzance in Cornwall, destroying the village of Mousehole, in July of 1595. Drake continued stalking the Spanish. He suggested a raid on Panama and the Queen agreed. During this fruitless mission, he contracted dysentery (“the bloody flux”) at Panama and died on January 29, 1596. Officially, Francis Drake “dyed without Issue” and was buried at sea.

Review of the author’s work by BC Studies:

The Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake, 1577-1580

BOOKS:

Fletcher, Francis. The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (London: Nicholas Bourne, 1628).

W. S. W. Vaux, ed., The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake (London: Hakluyt Society, 1856)

ALSO:

Julian S. Corbett, Drake and the Tudor Navy (London, 1898)

G. Davidson, Francis Drake on the Northwest Coast of America in the Year 1579 (San Francisco: Geographical Society of the Pacific, 1908)

N. M. Penzer, ed., The World Encompassed and Analogous Contemporary Documents Concerning Sir Francis Drake’s Circumnavigation of the World (New York, 1926)

John Robertson, Francis Drake and Other Early Explorers Along the Pacific Coast (San Francisco, 1927)

R.P. Bishop. Drake’s Course in the North Pacific. (British Columbia Historical Quarterly 3, 1939)

Herbert E. Bolton, et al, The Plate of Brass: Evidence of the Visit of Francis Drake to California in the Year 1579 (San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1953)

Andrews, Kenneth R. Drake’s Voyages: A Re-assessment of their Place in Elizabethan Maritime Expansion (New York: Scribner, 1967)

Raymond Aker, Report of Findings Relating to Identification of Sir Francis Drake’s Encampment at Point Reyes National Seashore Point Reyes, California (Drake Navigators Guild, 1970)

Helen Wallis, The Voyage of Sir Francis Drake Mapped in Silver and Gold (Berkeley: Friends of the Bancroft Library, 1974)

J. D. Hart, The Plate of Brass Reexamined: A Report Issued by The Bancroft Library 1977 (Berkeley: Bancroft Library, 1977)

J. D. Hart, The Plate of Brass Reexamined: A Supplementary Report Issued by The Bancroft Library 1979 (Berkeley: Bancroft Library, 1979)

R. C. Thomas, Drake at Olomp-ali (San Francisco: A-Pala Press, 1979)

Thrower, Norman J.W. (editor). Francis Drake and the Famous Voyage, 1577-1580 (University of California Press, 1984)

Bawlf, Samuel Sir Francis Drake and his Secret Voyage 1577-1580 (Douglas & McIntyre, 2003) 1-55054-977-4

[Alan Twigg / BCBW 2016] “1500-1700” “English” “Biography”

edit article delete article

from Warren Stevenson

Generating some discussion about renaming British Columbia is an excellent idea. I happen to think that the name “British Columbia,” which Queen Victoria chose a century-and-a-half ago, has served us well, all things considered, but agree that it now sounds ‘veddy colonial’ and old hat.

It’s all very well for the provincial capital, Victoria, to have a newspaper quaintly called The Colonist, but let’s remember that Vancouver, besides being the only Canadian city mentioned in James Joyce’s still futuristic Finnegan’s Wake, is also the westernmost metropolis in the Western Hemisphere, hence a pivotal point in the greater scheme of things.

With these thoughts in mind I do have a suggestion for a new name. We could do a lot worse than go back to the first recorded name possibly applied by a European to this territory (or, rather, its southwestern corner)—New Albion.

After spend some six weeks during the summer of 1579 careening his ship, the Golden Hinde (which had itself undergone a name-change upon entering the Pacific) preparatory to continuing on his epic voyage around the world, which, unlike his predecessor Magellan, he was able to complete in person, mastermariner Francis Drake bestowed the name New Albion on Pacific coastal territory.

Exactly where Drake applied the name remains open to dispute, but we know from the Diary of the Golden Hinde’s chaplain, Francis Fletcher, that Drake chose the name New Albion for two reasons: “the one in respect of the white bancks and cliffs which lie towards the sea; the other, that it might haue some affinity even in name also with or owne country, which was sometimes so called.”

Drake’s men nailed a brass plate onto a wooden post with an inscription mentioning New Albion incised thereon and a round hole with an English sixpence showing through from the other side, to which it was soldered. (Albion, the eponymous name of a giant in ancient British mythology, comes from the Latin albus, meaning white.)

Following two recent books—the second an augmentation of the first—by Sam Bawlf concerning Drake’s “secret voyage,” I am one of those who choose to believe that New Albion was, in all probability, hereabouts. The Drake-Hondius map of New Albion, in my opinion, matches Boundary Bay better than anywhere else along the Northwest Coast, and (to cite a less well-known piece of evidence that has recently come my way) since the palisaded fort “at the foot of a hill” which Fletcher avers Drake and his men built upon their arrival would have to have been near freshwater, it was probably in the region of what is now Crescent Beach at the mouth of the Nicomeki River.

The exact site might have impinged on native fishing rights, and nearby hilly Ocean Park has a street named Old Indian Fort Road to commemorate the location of a palisaded Indian fort, in itself unusual, perhaps a structural descendant of Drake’s fort, and leaving ruins known to have been there within living memory.

Albion eventually became a poetical name for England found in the works of (among others) Spenser, Shakespeare and William Blake. There is an ancillary Scottish legend about a giant named ‘Albyn’ which may go back to the Albanians, who seem to have shared with their Celtic counterparts a love of rugged mountains, kilts and bagpipes, if not of oatmeal. Myth tends to be timeless as well as inclusive, at least this one does, and in Blake’s illuminated epic poem Jerusalem, Albion symbolized the fall and regeneration of mankind.

Of course my new name suggestion, if adopted, would entail other changes. BC BookWorld would have to become NA BookWorld. And ICBC would become ICNA—short for “I see New Albion,” another way of saying, “I see the Promised Land.”

[Warren Stevenson wrote this commentary from White Rock in 2007 at the invitation of BC BookWorld publisher Alan Twigg.]

Leave a Reply