#128 Roderick Haig-Brown

February 22nd, 2016

LOCATION: Above Tide, 2250 Campbell River Road, Campbell River.

DIRECTIONS: Turn left onto Highway 19A from Highway 19 if proceeding north. It’s only two minutes or so from ‘downtown’ Campbell River.

Situated on the banks of the Campbell River, the former home of Roderick Haig-Brown and his family was known as Above Tide. Now owned by the City of Campbell River and called the Haig-Brown Heritage House, it is managed by the Campbell River Museum and operates as Bed and Breakfast from May to October. As one of the province’s few designated literary landmarks, it hosts a Writer in Residence program, in partnership with Canada Council, from December to April each year. A highlight of public tours, coordinated through the museum, is the extensive private library of Roderick Haig-Brown who credited his wife, Ann Haig-Brown, who typed his manuscripts, as being the family’s superior intellectual.

QUICK ENTRY:

The Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize for best book contributing to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia is named in honour of the Campbell River angler and essayist. His name will also endure for his foresight as a conservationist long before the word “environment” became common. He once wrote, “Can man make a rational response to his knowledge of the environment? Can he become sensitive, generous, and considerate to his world and the other creatures that share it with him, or is his nature immutably rooted in blood, sex and darkness?”

To favour any one of the 26 Haig-Brown titles between Silver: The Life Story of an Atlantic Salmon (1931) to The Salmon (1974), one might well agree with the editors of the anthology Genius of Place (2000) and select his meditations on life and nature near the midway point of his career, Measure of the Year (1950). In an excerpt entitled “Let Them Eat Sawdust,” he writes: “I think there has never been, in any state, a conservationist government, because there has never been a people with sufficient humility to take conservation seriously. . . . Conservation means fair and honest dealing with the future, usually at some cost to the immediate present.” A juvenile novel, Starbuck Valley Winter (1943), has been cited as Haig-Brown’s bestselling title. An angling classic, A River Never Sleeps (1946), guides the reader through the course of a fictional fishing year, visiting different rivers month by month. Adult novels Timber (1942) and On the Highest Hill (1949) concern life in the logging camps.

Roderick Haig-Brown was born in 1908 in Sussex, England. His mother was from a wealthy family in the brewery business. As a teenager, Haig-Brown met Thomas Hardy. A family friend, Major Greenhill, inspired his refined appreciation for hunting and fishing. Expelled from Charterhouse School for drinking and unsanctioned absenteeism, he persuaded his mother to send him to Seattle to visit his uncle, promising to return when he was of an age to apply for entry into the civil service. After working in a lumber camp in Washington State, he came north to avoid visa problems, spending three years in the Nimpkish Lake area of Vancouver Island, variously employed as a logger, guide and fisherman.

In Seattle he had met his future wife Ann Elmore, also born in 1908. They married in 1934 and took up residence on the banks of the Campbell River where they lived until their deaths: Roderick in 1976 and Ann in 1990. Their “Above Tide” residence is preserved as a heritage site. Valerie Haig-Brown edited some of her father’s books; Alan and Celia Haig-Brown are significant authors.

The pipe-smoker with a hyphenated name never attended university, but Haig-Brown served ably as a lay magistrate for northern Vancouver Island from 1941 until 1974. He also served as Chancellor of the University of Victoria from 1970 to 1973. E. Bennett Metcalfe published a controversial but intriguing biography called A Man of Some Importance (1985) “to rescue Haig-Brown from the myth-makers.” It was loathed and fiercely repressed by Haig-Brown’s widow. Anthony Robertson, Valerie Haig-Brown and Robert Cave have produced more laudatory books.

FULL ENTRY:

The Roderick Haig-Brown Book Prize for the best book contributing to the understanding and appreciation of British Columbia is named in honour of the Campbell River lay magistrate and essayist Roderick Haig-Brown who became known around the world for his writing about fishing and the environment.

To favour any one of the 26 Haig-Brown titles between Silver: The Life of an Atlantic Salmon (1931) to The Salmon (1974), one might well agree with the editors of the B.C. non-fiction anthology Genius of Place (2000) and select his meditations on life and nature near the midway point of his career, Measure of the Year (1950). In an except entitled ‘Let Them Eat Sawdust,’ he writes: “I think there has never been, in any state, a conservationist government, because there has never been a people with sufficient humility to take conservation seriously… Conservation means fair and honest dealing with the future, usually at some cost to the immediate present.”

Roderick Haig-Brown was born on February 21, 1908, in Lancing, Sussex, England, the grandson of a Charterhouse School headmaster and the son of a teacher and writer, Alan Haig-Brown. His father Alan was killed as a World War II soldier in 1918, but Roderick retained lasting veneration for him as “an Edwardian: one of the young, the strong, the brave and the fair who had faith in their nation, their world and themselves.” His mother Violet Mary Pope was from a wealthy family in the brewery business. As a teenager, Roderick Haig-Brown met Thomas Hardy and later regretted not getting to know him better. A family friend, Major Greenhill, was his main influence for developing his refined appreciation for hunting and fishing. Expelled from Charterhouse School for drinking and unsanctioned absenteeism, he persuaded his mother to send him to Seattle to visit his uncle, promising to return when he was of an age to apply for entry into the civil service. After working in a lumber camp in Washington state, he came north to Canada to avoid visa problems, spending three years in the Nimpkish Lake area of Vancouver Island variously employed as a logger, guide and fisherman. He returned to live in London, England in 1931, the same year he published his first book, Silver: The Life of an Atlantic Salmon.

In Seattle he had met his future wife Ann Elmore, born on May 3, 1908 and raised in Seattle. They married in 1934 and took up residence on the banks of the Campbell River where they both lived until their deaths (Roderick October, 19, 1976; Ann 1990). Their ‘Above Tide’ residence has been preserved as a heritage site. Roderick Haig-Brown and Ann were devoted to the protection of B.C. rivers, particularly those on which wild salmon are dependent for their survival. He was a trustee of the Nature Conservancy of Canada, an advisor to the BC Wildlife Federation, a senior advisor to Trout Unlimited and the Federation of Flyfishers and a member of Federal Fisheries Development Council and the International Pacific Salmon Commission. In addition, Roderick Haig-Brown served as a lay magistrate for the northern Vancouver Island region from 1941 until 1974 even though the pipe-smoking Englishman with a hyphenated name had never attended university. He had friendships with influential members of the UBC English department, who sometimes visited on fishing trips, but for many years he was partially reliant on cheques from his family in England. In addition, Haig-Brown served as Chancellor of the University of Victoria from 1970 to 1973.

Roderick Haig-Brown wrote many natural history and conservation books as well as several novels and collections of essays. His adult novels Timber and On the Highest Hill concern life in the logging camps and wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. In the former, based on his own experiences in the woods, Haig-Brown writes of the friendship between two loggers and their involvement in the union movement. In the latter, Colin Ensley, a shy and solitary young man, is deeply in love with a woman and with the northwest woods, leading to a tragic conclusion. In his attempt to write a novel of social criticism, Haig-Brown, the conservationist, can be viewed as a post-D.H. Lawrence philosopher, protesting what Laurie Ricou has called ‘the machine in the garden’. Haig-Brown’s work continues to be reprinted, particularly titles pertaining to fishing.

E. Bennett (Ben) Metcalfe published a controversial but intriguing biography called A Man of Some Importance “to rescue Haig-Brown from the myth-makers.” It was loathed and repressed by Haig-Brown’s widow, a fierce protector of his reputation. Campbell River publisher Neil Cameron and fishing expert Van Egan, a long-time friend of Haig-Brown, are preparing a new memoir by Van Egan about Haig-Brown, whose best known titles, according to family historian Valerie Haig-Brown, are A River Never Sleeps and Measure of the Year. Revered as an angling classic, A River Never Sleeps guides the reader through the course of a fictional fishing year, visiting different rivers month by month, starting with steelhead fishing, gradually leading down to the sea and the spawning of salmon. Reprinted many times, it is concurrently an almanac of his fishing life from English chalkstreams of his youth to the unspoiled rivers of streams of the Pacific Northwest.

According to bibliographer Robert Bruce Cave, the biggest selling single edition of any book he wrote was the second American edition of Starbuck Valley Winter which reputedly sold 80,000 copies between 1949 and 1956. In 2000, Cave privately published an exhaustive inventory of Haig-Brown’s literary work entitled Roderick Haig-Brown: A Descriptive Bibliography.

According to researcher Andrew Irvine, who extensively researched an article for Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada entitled Bibliographical Errata Regarding the Cumulative List of Winners of the Governor General’s Literary Awards, Roderick Haig-Brown received the first and only Governor General’s Citation for Juvenile Literature for his 1948 book, Saltwater Summer, rather than the traditional medal that was accorded thereafter. His name has subsequently been omitted from the official list of winners that is maintained by the Canada Council for the Arts. Since 1936, the venerable Governor General’s Awards long remained the foremost literary prizes in Canada until the onset of the glitzy, lucrative Giller Prize stole the spotlight.

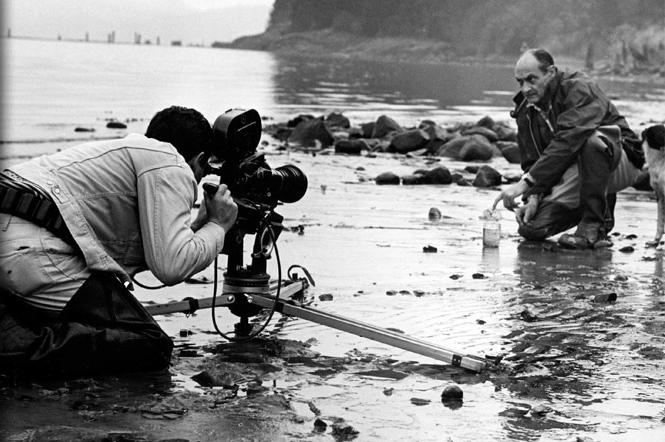

At the Campbell River Museum visitors can watch a documentary film on the life of Roderick Haig-Brown, Fisherman’s Fall, in the 30-seat Van Isle Theatre.

Two of his four children, Alan and Celia Haig-Brown, have become significant authors of books pertaining to British Columbia.

Review of the author’s work by BC Studies:

On the Highest Hill

Measure of the Year: Reflections on Home, Family, and a Life Fully Lived

Starbuck Valley Winter

Silver: The Story of an Atlantic Salmon (London: A & C Black, 1931)

Pool and Rapid (London: Jonathan Cape, 1932)

Panther (1934) or Kiyu: A Story of Panthers (1934). Reprinted by Harbour Publishing, 2007.

The Western Angler (New York: Derrydale Press, 1939)

Return to the River: A Story of the Chinook Run (1941; McClelland & Stewart, 1946)

Timber (Morrow, 1942; William Collins, 1946)

Starbuck Valley Winter (1943)

A River Never Sleeps (New York: William Morrow; Lyons & Burford, 1946; UK edition, London: Collins, 1948)

Saltwater Summer (1948)

On the Highest Hill (Toronto: Collins, 1949)

Measure of the Year (1950)

Fisherman’s Spring (1951)

Canada’s Pacific Salmon (1952)

Divine Discontent (1953)

Fisherman’s Winter (1953)

Mounted Police Patrol (1954)

The Case for the Preservation of Strathcona Park (1955)

Captain of the Discovery: The Story of George Vancouver (Toronto: Macmillan, 1956; Toronto: Macmillan, 1972).

Sport Fish Resources of British Columbia. Part IV: A General Evaluation (1956)

Fisherman’s Summer (1959)

The Farthest Shores (Toronto: Longmans, 1960)

The Living Land: An Account of the Natural Resources of British Columbia (Toronto: Macmillan, 1961)

Fur and Gold (Toronto: Longmans, 1962)

The Whale People (Collins, 1962) – juvenile novel

A Primer of Fly Fishing (1964)

Fisherman’s Fall (1964)

Sport Fisheries: General Evaluation (1964)

The Fraser Watershed & The Moran Proposal (1972)

The Salmon (Ottawa: Environment Canada, 1974)

Bright Waters, Bright Fish: An Examination of Angling in Canada (Douglas & McIntyre, 1980)

De Poissons vifs sur Champ d’Ecume (1980)

Alison’s Fishing Birds (Vancouver: Colophon Books, 1980)

Woods and River Tales (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1980)

The Master and His Fish (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1981)

Writings and Reflections (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1982)

The Diaries of Roderick Haig-Brown: 1927-1929 and 1932-1933 (1994)

To Know a River: A Haig-Brown Reader (1996)

On Making A Library [Alcuin Society Keepsake for Haig-Brown Book Fair, Campbell River, 2004] (Vancouver: Alcuin Society, 2004).

BOOKS AND BOOKLETS ABOUT HAIG-BROWN

Cave, Robert Bruce. Roderick Haig-Brown: A Descriptive Bibliography. Citrus Heights, CA: Privately published, 2000

Egan, Van. For the Love of the River. Campbell River: Campbell River Arts Council/Haig-Brown Institute/Museum at Campbell River, 2009

Haig-Brown Family: Mary, Valerie, Alan, Celia. What We Learned. Campbell River: Campbell River Arts Council/Haig-Brown Institute/Museum at Campbell River, 2012

Haig-Brown, Valerie. Deep Currents: Roderick and Ann Haig-Brown. Victoria: Orca Book Publishers, 1997

Metcalfe, Bennett. A Man of Some Importance: The Life of Roderick Langmere Haig-Brown. Seattle & Vancouver: James W. Wood Publishers, 1985

Purdy, Al. Cougar Hunter: A Memoir of Roderick Haig-Brown. Vancouver: The Phoenix Press, 1992

Robertson, Anthony. Above Tide: Reflections on Roderick Haig-Brown. Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 1984

Leave a Reply