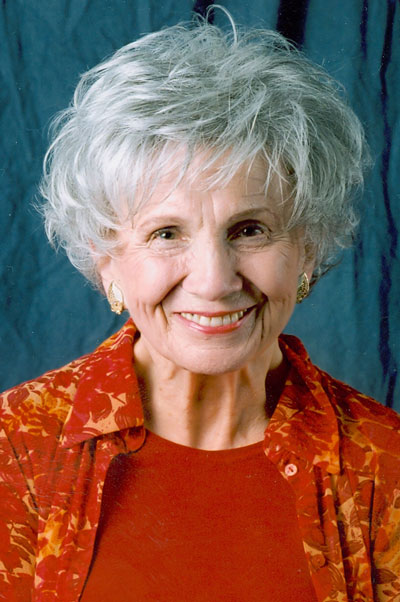

#119 Alice Munro

February 02nd, 2016

LOCATION: Kitsilano Public Library, 2425 MacDonald St., Vancouver

The first Canadian author to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, Alice Munro, first worked in the Vancouver Public Library prior to becoming an acclaimed short story writer and a mother. As outlined in a biography by Robert Thacker, within a month of her arrival in Vancouver in 1952 with her new husband, Jim Munro (who would eventually own and operate Munro’s Books in Victoria), Alice Munro got a part-time job at the Kitsilano branch of the Vancouver Public Library. She worked part-time for VPL until the fall of 1952, then full-time until June of 1953. After her first daughter, Sheila, was born in October of 1953, she worked part-time until her next pregnancy in 1955.

LITERARY LOCATION #2: 2749 Lawson Avenue, West Vancouver. Go over the Lions Gate Bridge from Vancouver, proceed west along Marine Drive to 25th Avenue & Marine, turn right up the hill on 25th, left onto Lawson, proceed one-and-a-half blocks.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro lived here with two young daughters above Dundarave village. She and her husband Jim Munro became friendly with two other couples in the area, Harry and Jessie Webb, who were bohemian artists at 2476 Bellevue Avenue, near the Dundarave pier; and editor/writers Stephen and Elsa Franklin who were planning to open the Pick-a-Pocket Bookshop at 2442 Marine Drive. The Franklins were commissioned to design the bookstore’s interior; the Munros were initially going to be partners. After the bookstore became a fixture on the same side of the street as Libby’s Drugstore, the Franklins moved east to Ontario where Elsa Franklin became the manager of Pierre Berton’s career. Jim Munro received the Order of Canada for operating Munro’s Books in Victoria from 1963 onward, but the initial impulse to operate a bookstore arose from Pick-a-Pocket Books in Dundarave, still a laid-back enclave where Alice Munro once briefly rented an office in order to write.

QUICK ENTRY:

Many would argue Alice Munro is the finest writer Canada has produced. In 2013 she became the first Canadian to be accorded the Nobel Prize for Literature. [Scroll down to the bottom of this entry to find her editor Doug Gibson’s excellent eyewitness account of the ceremony.] It is impossible to select one collection of her short stories as being superior to the rest.

Winner of the 2009 Man Booker International Prize, twice winner of the Giller Prize (Canada’s most glitzy literary prize), three times the recipient of the Governor General’s Award for Fiction (Canada’s most venerable literary prize), Alice Munro is peerless. Her work has gained her the distinction, accorded by the New York Times, of being “the only living writer in the English language to have made a major career out of short fiction alone.” In 2004, that newspaper also produced the oft-repeated compliment, “More than any writer since Chekhov, Munro strives for and achieves, in each of her stories, a gestalt-like completeness in the representation of a life.”

In 2005, Alice Munro accepted the 11th George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award for an Outstanding Literary Career in British Columbia, but most readers assume she is an Ontario writer.

Born as Alice Laidlaw in Ontario in 1931, she married fellow student Jim Munro in 1951 and reluctantly moved to Vancouver in 1952 after her husband had secured a good job in a department store. First they lived across from Kitsilano Beach in a basement suite of a three-storey building at Arbutus and Cornwall among “high wooden houses crammed with people living tight.”

In 1953, they moved briefly to a drab house in North Vancouver before settling in the relative security of upwardly mobile but yet-to-be pretentious West Vancouver. Here her two eldest daughters, Sheila and Jenny, were born. Another died the day she was born. While writing in West Vancouver, she befriended fellow Vancouver homemaker Margaret Laurence and they were both encouraged by Ethel Wilson. It was not all sweetness and light. For a New York Times article in 2006, her daughter Sheila recalled, “When I got home from school my mother would be sitting in that chair in the living room in the dark… She just wanted to be left alone to write.”

Despite being left to her own devices at home in West Vancouver, Alice Munro never learned to drive. In 1963, the Munros moved to Victoria and opened Munro’s Books. (Long considered one of the finest independent bookstores in Canada, Munro’s Books would mark its 50th anniversary in the same year that Alice Munro won the Nobel Prize.)

According to historian Eve Lazarus, at first the Munros lived in a rented house in Victoria at 105 Cook Street. In 1966, Alice Munro gave birth to her youngest daughter, Andrea, and the family bought a Tudor Revival mansion in Rockland, listed for $30,000. An offer of $20,000 was accepted. It had five fireplaces, high ceilings and a nanny’s quarters. The heritage home was reputedly built in 1894 and designed by Francis Rattenbury, but there are no records to verify it. Houseguests would include Margaret Atwood, Dorothy Livesay, Audrey Thomas and P.K. Page.

In all, Alice Munro lived in Vancouver and Victoria for 22 years before her first marriage ended and she moved back to Ontario. After her divorce in 1972, Alice Munro married former university friend, Gerald Fremlin, a geographer/cartographer, in 1976. Jim Munro married textile artist Carole Sabiston in 1977, and they remained in the Rockland house. Fremlin died on April 17, 2013.

For several years, Alice Munro maintained two residences: one in Clinton, Ontario, and another in Comox, on Vancouver Island. She received the news of her Nobel Prize at 4 a.m. while visiting one of her daughters in Victoria. “It just seems impossible,” she told the CBC. “It seems just so splendid a thing to happen, I can’t describe it, it’s more than I can say.”

Alice Munro’s dual status as a British Columbian and an Ontario resident is often overlooked. “I like the West Coast attitudes,” she said in 2004. “Winters [in B.C.] to me are sort of like a holiday. People are thinking about themselves. The way I grew up, people were thinking about duty.” One can suggest the dichotomy between duty and exploration is a fundamental friction in her stories; and the geographical disparity between unruly British Columbia and hidebound Ontario matches her character.

Alice Munro made her critically acclaimed debut with Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), written mostly on Cook Street. Her second book, Lives of Girls and Women (1971), was the basis for a Canadian movie. In addition, Sarah Polley adapted the story “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” for the film Away from Her (2006), starring Julie Christie and Gordon Pinsent. Most of Alice Munro’s books have been edited by Douglas Gibson, also her publisher, at Douglas Gibson Books, an imprint of McClelland & Stewart, formerly Canada’s leading publishing house for literature. Gibson lives in Toronto.

With her mother’s encouragement and consent, Sheila Munro, while living in Powell River, published an astute study of their family dynamics and her mother’s books, Lives of Mothers and Daughters (2001).

ENTRY:

Winner of the 2009 Man Booker International Prize, twice winner of the Giller Prize; three times the recipient of the Governor General’s Award for Fiction, Alice Munro is peerless. In 2013 she became the first Canadian and only the thirteenth woman to be accorded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Her work has gained her the distinction accorded by the New York Times as “the only living writer in the English language to have made a major career out of short fiction alone.” She is also the recipient of the 11th George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award for an Outstanding Literary Career in British Columbia. “Alice Munro has devoted her career to the short story,” wrote a reviewer for The Times (U.K.), “and when reading her work it is difficult to remember why the novel was ever invented.”

Alice Munro was born Alice Ann Laidlaw in Wingham, Ontario on July 10, 1931. She was raised on a farm with a sister and a brother. Before he turned his hand to farming, her father, Robert Eric Laidlaw, had raised foxes and minks and worked as a watch-man. Her mother, Anne Clarke Laidlaw, was a former teacher who developed Parkinson’s disease and died in 1959. While she undertook a large share of the domestic duties, Alice Laidlaw nursed her improbable ambitions to become a writer. “I think choosing to be a writer was a very reckless thing to do,” she told CBC’s Shelagh Rogers in 2004, “although I didn’t realize it. I was planning an historical novel in grade seven. It gave way to a Wuthering Heights novel I was writing all the way through high school.” Alice Munro has also said, “My oddity just shone out of me.”

At age eighteen, Munro won a scholarship to the University of Western Ontario where she studied for two years; published her first short story, ‘The Dimensions of a Shadow’, in 1950, in Folio, an undergraduate literary magazine; and she met fellow student Jim Munro. They married in December of 1951 and moved to Vancouver where their two eldest daughters were born. Another daughter died of kidney failure on the day she was born.

In Vancouver Alice Munro befriended Margaret Laurence, another housewife who was learning to write, and she was inspired by the success of local novelist Ethel Wilson, who she also met. Encouraged by her first husband to pursue her writing when they resided in West Vancouver, Alice Munro once rented a small office for herself in Dundarave, which became the basis of a story about a female writer being unable to escape the role of caring for others. As a mother, Munro has been described by one of her daughters as more of a watcher than a nurturer.

In Victoria, where a fourth daughter was born, she helped establish Munro’s Books, opened in 1963, now generally considered one of the finest independent bookstores in Canada, and she gave birth to her youngest daughter in 1966. She resided in Vancouver and Victoria for 22 years before her first marriage ended and she moved back to Ontario.

After separating from her husband in 1973, Alice Munro became writer-in-residence at the University of Western Ontario in 1974. In 1975, she moved to Clinton, Ontario, in Huron County, with a former university friend, Gerald Fremlin, a geographer, partially in order to help look after his mother. Clinton is located approximately 35 kilometres from Wingham where she grew up. (The issue of Folio in which she had first published a short story also contained a story by Fremlin, who is slightly older than her.)

Alice Munro married Fremlin after she was divorced in 1976, the year she received her first honorary doctorate (having been unable to finish university due to lack of funds). For many years Alice Munro divided her time between residences in Clinton in Ontario and Comox on Vancouver Island.

***

Encouraged by CBC’s Radio’s Robert Weaver since 1951, Alice Munro sold her first short story to Mayfair magazine in 1953. “I never intended to be a short-story writer,” Munro once said. She has suggested she might have opted for the short story approach to fiction because she was balancing her duties as the mother of three children, but she also spent many of her formative years as writer trying to write a novel without success. Alice Munro’s first short story collection, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), received the Governor General’s Award for Fiction.

Her follow-up, Lives of Girls and Women (1971), was marketed as a novel and received the Canadian Booksellers Award. Her reputation began spreading to the United States. “The short story is alive and well in Canada,” wrote Martin Levin in The New York Times (September 23, 1973), reviewing Dance of the Happy Shades, “where most of the 15 tales originate like a fresh winds from the North.”

A frequent contributor to the New Yorker magazine since 1976, Alice Munro has firmly established her reputation as Canada’s most consistent writer with her impeccable style and exacting perceptions. All her books have been well-received and feature heroines who seek some measure of control over their lives through understanding, while flirting with recklessness. “The complexity of things — the things within things — just seems to be endless,” Munro has said. “I mean nothing is easy, nothing is simple.”

Munro’s work has received many literary prizes, including three Governor General’s Awards, the Giller Prize, a Canada Council Molson’s Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Prize, the first Canada-Australia Literary Prize and the first Marian Engel Award. She is the first Canadian to receive the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in Short Fiction and the Rea Award for lifetime achievement in short stories.

Alice Munro’s Runaway (2004) has eight stories that reflect her dual hometowns of Comox and Clinton. More than one reviewer has suggested it’s impossible to characterize the subject matter of Runaway because Munro’s beguiling stories are so multi-layered and diverse, but she has herself noted, “what I wanted to do in this book was take these sharp turns in people’s lives.” Three linked tales follow Juliet, a young teacher who visits her fisherman lover’s home the day after his wife’s funeral. In the title story, Munro keeps the reader guessing as to how a white goat’s disappearances relates to a couple’s unraveling relationship. The final story covers almost a lifetime in its 65 pages. The collection earned Munro her second Giller Prize and numerous other awards.

In the early 1990s Alice Munro began spending her winters in Comox, on Vancouver Island, keeping a low profile. Her daughter Sheila Munro published an astute and revealing autobiographical and critical study of their family relationship and her mother’s books, Lives of Mothers and Daughters (2001), with Alice Munro’s encouragement and consent. [See Sheila Munro entry] An authorized and respectful biography by Robert Thacker appeared four years later.

Lives of Girls and Women was the basis for a Canadian movie that featured Munro’s daughter Jenny as the heroine Del Jordan. A short film adaptation of her story ‘Boys and Girls’ won an Oscar in 1984. Sarah Polley’s superb cinematic adaptation of Alice Munro’s story ‘The Bear Came Over the Mountain,’ renamed Away from Her and starring Julie Christie and Gordon Pinsent, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Alice Munro became only the third recipient of the new Man Booker International Prize in June of 2009. Certainly part of her appeal is that her work is distinctly Canadian in a classic ‘Who Do You Think You Are’ mold: It is imperative not to get uppity, to eschew arrogance, or at least feign humility. Typically, she told her Man Booker audience at Trinity College in Ireland that writing, for her, has always amounted to “always fooling around with what you find. … This is what you want to do with your time—and people give you a prize for it.”

In one of the more believable stories in Too Much Happiness, entitled ‘Fiction,’ a graduate of UBC Creative Writing department has published her first collection of stories called How Are We To Live. The protagonist, Joyce, is an older woman who once gave this girl music lessons as a child. She has realized this up’-n’-coming writer is the daughter of the woman to whom she lost her first husband when they were all living at place called Rough River, decades before.

Curiosity sends Joyce to the author’s book launch at a North Vancouver bookstore. From her classically Canadian perspective, Munro writes, “Joyce has never understood this business of lining up to get a glimpse of the author and then going away with a stranger’s name written in your book.” The self-confident young author has written a story that completely documents the domestic complications that were witnessed as a child, the various intrigues that led to Joyce’s divorce, and yet she does not recognize her former music teacher in the flesh. She is very busy taking herself seriously as an author. There is a poster of her wearing a little black jacket, tailored, severe, very low in the neck, and Munro adds, “Though she has practically nothing there to show off.”

This is about as scathing as Alice Munro gets. The self-satisfied young author has simply reiterated reality without going to trouble of fictionalizing it, adding nuances of her own. This writer “sits there and writes her name as if that is all the writing she could be responsible for in this world.” Then there is a line break. An open space on the page. A reprieve. The once-jilted Joyce, since remarried to a 65-year-old neuropsychologist, has left the book signing. And Alice Munro adds a final paragraph.

“Walking up Lonsdale Avenue, walking uphill, she gradually regains her composure. This might even turn into a funny story that she would tell some day. She wouldn’t be surprised.”

SELECTED AWARDS: International Man Booker Prize, Governor General’s Award (3), PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in Short Fiction, Giller Prize (2), The Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, W.H. Smith Prize in the U.K., National Book Circle Critics Award in the U.S., Trillium Prize, Molson’s Prize, Libris Award, Rea Award for Lifetime Achievement, Terasen Lifetime Achievement Award (renamed George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award). Harbourfront Prize, 2013. Nobel Prize for Literature, 2013.

BOOKS:

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

LIVES OF GIRLS AND WOMEN (1971)

SOMETHING I’VE BEEN MEANING TO TELL YOU (1974)

WHO DO YOU THINK YOU ARE? (1978). Published as THE BEGGAR MAID: STORIES OF FLO AND ROSE in the United States and U.K. (1978)

THE MOONS OF JUPITER (1983)

THE PROGRESS OF LOVE (1986)

FRIEND OF MY YOUTH (1990)

OPEN SECRETS (1994)

SELECTED STORIES (1996)

THE LOVE OF A GOOD WOMAN (1998)

HATESHIP, FRIENDSHIP, COURTSHIP, LOVESHIP, MARRIAGE (2001)

RUNAWAY (2004)

THE VIEW FROM CASTLE ROCK (2006)

ALICE MUNRO’S BEST: SELECTED STORIES (2008)

TOO MUCH HAPPINESS (2009)

DEAR LIFE (2012)

Also:

Munro, Sheila. Lives of Mothers and Daughters (M&S, 2001).

Thacker, Robert. Alice Munro: Writing her Lives (M&S, 2005).

Short Story Compilations

Selected Stories – 1996

No Love Lost – 2003

Vintage Munro – 2004

Carried Away: A Selection of Stories – 2006

New Selected Stories – 2011

Plus:

Probable Fictions: Alice Munro’s Narrative Acts, ed. by Louis K. Mackendrick (1981); Controlling the Uncontrollable: The Fiction of Alice Munro by Ildiko De Papp Carrington (1989); Dance of the Sexes: Art and Gender in the Fiction of Alice Munro by Beverly Rasporich (1990); Alice Munro: A Double Life by Catherine Ross (1992); The Tumble of Reason: Alice Munro’s Discourse of Absence by Ajay Heble (1994); The Influence of Painting on Five Canadian Writers by John Cooke (1996); Alice Munro by Coral Ann Howells (1998); The Rest of the Story: Critical Essays on Alice Munro, ed. by Robert Thacker (1999); Reading in: Alice Munro’s Archives by Joann McCaig (2002). Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013 by Robert Thacker (University of Calgary Press 2015).

ALICE MUNRO INTERVIEW (1978) by Alan Twigg

When Alice Munro resided in Clinton, Ontario, she was interviewed by Alice Munro in 1978. This interview was first published in For Openers: Conversations with 24 Canadian Writers (Harbour 1981). It was reprinted in Strong Voices: Conversations with 50 Canadian Writers (Harbour 1988).

T: Your writing is like the perfect literary equivalent of a documentary movie.

MUNRO: That is the way I see it. That’s the way I want it to be.

T: So it’s especially alarming when Lives of Girls and Women gets removed from a reading list in an Ontario high school. Essentially all they’re objecting to is the truth.

MUNRO: This has been happening in Huron County, where I live. They wanted The Diviners, Of Mice and Men and Catcher in the Rye taken off, too. They succeeded in getting The Diviners taken off. It doesn’t particularly bother me about my book because my book is going to be around in the bookstores. But the impulse behind what they are doing bothers me a great deal. There is such a total lack of appreciation of what literature is about! They feel literature is there to teach some great moral lesson. They always see literature as an influence, not as an opener of live. The lessons they want taught are those of fundamentalist Christianity and if literature doesn’t do this, it’s a harmful influence.

They talk about protecting their children from these books. The whole concept of protecting eighteen-year old children from sexuality is pretty scary and pretty sad. Nobody’s being forced to read these books anyway. The news stories never mention that these books are only options. So they’re not just protecting their own children. What they’re doing is removing the books from other people’s children.

T: Removing your books seems especially absurd because there’s so little preaching for any particular morality or politics.

MUNRO: None at all. I couldn’t write that way if I tried. I back off my party line, even those with which I have a great deal of sympathy, once it gets hardened and insisted upon. I say to myself that’s not true all the time. That’s why I couldn’t write a straight women’s lib book to expose injustices. Everything’s so much more complicated than that.

T: Which brings us to why you write. Atwood’s theory on Del Jordan in Girls and Women is that she writes as an act of redemption. How much do you think your own writing is a compensation for loss of the past?

MUNRO: Redemption is a pretty strong word. My writing has become a way of dealing with life, hanging onto it by re-creation. That’s important. But it’s also a way of getting on top of experience. We all have life rushing in on us. A writer pretends, by writing about it, to have control Of course a writer actually has no more control than anybody else.

T: Do you think you’ve chosen the short story form because that requires the most discipline and you come from a very restrictive background?

MUNRO: That’s interesting. Nobody has suggested that before. I’ve never known why I’ve chosen the short story form. I guess in a short story you impose discipline rather soon. Things don’t get away from you. Perhaps I’m afraid of other forms where things just flow out. I have a friend who writes novels. She never touches what she’s written on the day she’s written it. She could consider it fake to go aback and rework the material. It has to be how the work flows out of her. Something about that makes me very uneasy. I could never do it.

T: You’re suspicious of spontaneity?

MUNRO: I suppose so. I’m not afraid spontaneity would betray me because I’ve done some fairly self exposing things. But I’m afraid it would be repetitious and boring if I wrote that way. It’s as if I must take great care over everything. Instead of splashing the colours of and trusting they will all come together, I have to know the design.

T: Do ideas ever evolve into something too big for a short story?

MUNRO: Yes

T: I thought the title story of Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You was a good example of that. It didn’t work because you were dealing with the lifetimes of four different characters.

MUNRO: You know I really wanted to write a novel of that story. Then it just sort of boiled down like maple syrup. All I had left was that story. For me it would have been daring to stretch that material out into a full novel. I wouldn’t be sure of it. I wouldn’t be sure it had the strength. So I don’t take that chance.

T: Do you write your stories primarily for magazines now, or for eventual inclusion in a book?

MUNRO: Writing for magazines is a very sideline thing. It’s what enables me to survive financially, but it isn’t important to me artistically. Right now I’m working on some stories and I might not be able to sell any of them. This has happened to very established writers. Markets are always changing. They say to begin writers study the market. That’s no use at all. The only thing you can do is write what you want.

T: You once said that the emotional realism of your work is solidly autobiographical. Is that how your stories get started? When something triggers you back to an emotional experience?

MUNRO: Yes. Some incident that might have happened to me or to somebody else. It doesn’t matter which. As long as it’s getting at some kind of emotional core that I want to investigate.

T: Do ever worry that goldmine of your past will dry up?

MUNRO: I never know. I never know. I thought I had used it all up before I started this book. Now I’m writing out of a different period. I’m very interested in my young adulthood.

T: Has there been a lot of correlation between your writing and raising your daughters?

MUNRO: Tremendously. When I was writing Lives of Girls and Women, some of the things in there came from things my daughters did when they were ten or eleven. It’s a really crazy age. they used to go to the park and hang down from their knees and scare people, pretending to be monkeys. I saw this wild, ferocious thing in them which gets dampened for most girls with puberty. Now my two older girls are twenty-five and twenty-one and they’re making me remember new things. Though they live lives so different from any life possible to me, there’s still similarities.

T: Do you feel a great weight has been lifted now your kids are older?

MUNRO: Yes. I’m definitely freer. But not to be looking after somebody is a strange feeling. All my life I’ve been doing it. Now I feel enormous guilt that I’m not responsible for anybody.

T: Maybe guilt is the great Canadian theme. Marian Engel wrote Canada is “a country that cannot be modern without guilt.” And Margaret Laurence said she came from “people who feel guilty at the drop of a hat, for whom virtue only arises from work.” Since intellectual work is not regarded by many people as real work, did you face any guilt about wanting to write?

MUNRO: Oh, yes. But it wasn’t guilt so much as embarrassment. I was doing something I couldn’t explain or justify. Then after a while I got used to being in that position. That’s maybe the reason I don’t want to go on living in Huron County. I notice when I move out and go to Toronto, I feel like an ordinary person.

T: Do you know where you got your ambition to write?

MUNRO: It was the only thing I ever wanted to do. I just kept on trying. I guess what happens when you’re young has a great deal to do with it. Isolation, feelings of power that don’t get out in a normal way, and maybe coping with unusual situations…most writers seem to have backgrounds like that.

T: When the kids play I Spy in your stories, they have a hard time finding colours. Was your upbringing really that bleak?

MUNRO: Fairly. I was a small child in the Depression. What happens at the school in the book you’re referring to is true. Nothing is invented.

T: So you really did take a temperance pledge in the seventh grade?

MUNRO: Yes, I did.

T: Sounds pretty bleak to me!

MUNRO: I thought my life was interesting! There was always a great sense of adventure, mainly because there were so many fights. Life was fairly dangerous. I lived in an area like West Hanratty in Who Do You Think You Are? We lived outside the whole social structure because we didn’t live in the town and we didn’t live in the country. We lived in this kind of little ghetto where all the bootleggers and prostitutes and hangers-on lived. Those were the people I knew. It was a community of outcasts. I had that feeling about myself.

When I was about twelve, my mother got Parkinson’s disease. It’s an incurable, slowly deteriorating illness which probably gave me a great sense of fatality. Of things not going well. But I wouldn’t say I was unhappy. I didn’t belong to any nice middle class so I got to know more types of kids. It didn’t seem bleak to me at the time. It seemed full of interest.

T: As Del Jordan says, “For what I wanted was every last thing, every layer of speech and thought, stroke of light on bark or walls, every small, pothole, pain-cracked illusion…”

MUNRO: That’s the getting everything-down compulsion.

T: Yet your work never reads like it’s therapy writing.

MUNRO: No, I don’t write just out of problems. I wrote even before I had problems!

T: I understand you’ve married again. And that it’s quite successful.

MUNRO: It’s a very happy relationship. I haven’t really dealt much with happy relationships. Writers don’t. They tell you about their tragedies. Happiness is a very hard thing to write about. You deal with it more often as a bubble that’s about to burst.

T: You have a quote about Rose in Who Do You Think You Are.?, “She thought how love removes the world.” With your writing you’re trying to get in touch with the world as much as possible, so does this mean that love and writing are adversaries?

MUNRO: Wordsworth said, “Poetry is emotion recollected in tranquillity.” You can follow from this that a constant state of emotion would be hostile to the writing state.

T: If you’re a writer, that could have some pretty heavy implications.

MUNRO: Very heavy. If you’re a writer, probably there’s something in you that makes you value your self, your own objectivity, so much that you can’t stand to be under the sway of another person. But then some people might say that writing is an escape, too. I think we all make choices about whether we want to spend our lives in emotional states.

T: That’s interesting. My wife’s comment on Who Do You Think You Are? was that your character Rose is never allowed to get anything. She’s always unfulfilled. Maybe she’s just wary of emotion.

MUNRO: She gets something. She gets herself. She doesn’t get the obvious things, the things she thinks she wants. Like in “Mischief,” which is about middle-aged infidelity, Rose really doesn’t want that love affair. What she does get is a way out of her marriage. She gets a knowledge of herself.

T: But only after a male decides the outcome of the relationship.

MUNRO: I see that as true in relations between men and women. Men seem to have more initiative to decide whether things happen or don’t happen. In this specific area women have had a lack of power, although it’s slowly changing.

T: When you write, “outrageous writers may bounce from one blessing to another nowadays, bewildered, as permissively raised children are said to be, by excess of approval,” I get the feeling you could just as easily substitute the word male for outrageous.

MUNRO: I think it’s still possible for men in public to be outrageous in ways that it’s not possible for women to be. It still seems to be true that no matter what a man does, there are women who will be in love with him. It’s not true the other way round. I think achievement and ability are positively attractive qualities in men that will overcome all kinds of behaviour and looks, but I don’t think the same is true for women.

A falling-down-drunk poet may have great power because he has talent. But I don’t think men are attracted to women for these reasons. If they are attracted to talent, it has to be combined with the traditionally attractive female qualities. If a woman comes on shouting and drinking and carrying on, she won’t be forgiven.

T: Whenever I ask writers about growing older, they not only answer the question, they respond to the question. I suspect you’re enjoying getting older, too.

MUNRO: Yes. Yes. I think it’s great. You just stop worrying about a lot of things you used to worry about. You get things in perspective. Since I turned forty I’ve been happier than ever before. I feel so much freer.

Alice Munro briefly rented an office to write in at the the Pick-a-Pocket Bookshop, 1962. Photo by Jessie Webb.

Runaway (2004): Review/Endorsement (NYT)

[There is such a wide concensus that Alice Munro is simply a ‘better’ writer than most, at the risk of infringing upon moral and legal rights of Jonathan Franzen, here is an excellent and representative review that appeared in the New York Times. This site does not, as a rule, use other people’s materials without permission, but for the sake of posterity, it seems necessary to validate the prevailing notion that Alice Munro is a British Columbia author unlike any other–consistently esteemed beyond Canada for most of her career.]

Runaway’: Alice’s Wonderland (2004)

By JONATHAN FRANZEN

Alice Munro has a strong claim to being the best fiction writer now working in North America, but outside of Canada, where her books are No. 1 best sellers, she has never had a large readership. At the risk of sounding like a pleader on behalf of yet another underappreciated writer — and maybe you’ve learned to recognize and evade these pleas? The same way you’ve learned not to open bulk mail from certain charities? Please give generously to Dawn Powell? Your contribution of just 15 minutes a week can help assure Joseph Roth of his rightful place in the modern canon? — I want to circle around Munro’s latest marvel of a book, ”Runaway,” by taking some guesses at why her excellence so dismayingly exceeds her fame.

1. Munro’s work is all about storytelling pleasure. The problem here being that many buyers of serious fiction seem rather ardently to prefer lyrical, tremblingly earnest, faux-literary stuff.

2. As long as you’re reading Munro, you’re failing to multitask by absorbing civics lessons or historical data. Her subject is people. People people people. If you read fiction about some enriching subject like Renaissance art or an important chapter in our nation’s history, you can be assured of feeling productive. But if the story is set in the modern world, and if the characters’ concerns are familiar to you, and if you become so involved with a book that you can’t put it down at bedtime, there exists a risk that you’re merely being entertained.

3. She doesn’t give her books grand titles like ”Canadian Pastoral,” ”Canadian Psycho,” ”Purple Canada,” ”In Canada” or ”The Plot Against Canada.” Also, she refuses to render vital dramatic moments in convenient discursive summary. Also, her rhetorical restraint and her excellent ear for dialogue and her almost pathological empathy for her characters have the costly effect of obscuring her authorial ego for many pages at a stretch. Also, her jacket photos show her smiling pleasantly, as if the reader were a friend, rather than wearing the kind of woeful scowl that signifies really serious literary intent.

4. The Swedish Royal Academy is taking a firm stand. Evidently, the feeling in Stockholm is that too many Canadians and too many pure short-story writers have already been given the Nobel. Enough is enough!

5. Munro writes fiction, and fiction is harder to review than nonfiction. Here’s Bill Clinton, he’s written a book about himself, and how interesting. How interesting. The author himself is interesting — can there be a better qualification for writing a book about Bill Clinton than actually being Bill Clinton? — and then, too, everybody has an opinion about Bill Clinton and wonders what Bill Clinton says and doesn’t say in his new book about himself, and how Bill Clinton spins this and refutes that, and before you know it the review has practically written itself.

But who is Alice Munro? She is the remote provider of intensely pleasurable private experiences. And since I’m not interested in reviewing her new book’s marketing campaign or in being entertainingly snarky at her expense, and since I’m reluctant to talk about the concrete meaning of her new work, because this is difficult to do without revealing too much plot, I’m probably better off just serving up a nice quote for Alfred A. Knopf to pull — ”Munro has a strong claim to being the best fiction writer now working in North America. ‘Runaway’ is a marvel” — and suggesting to the Book Review’s editors that they run the biggest possible photograph of Munro in the most prominent of places, plus a few smaller photos of mildly prurient interest (her kitchen? her children?) and maybe a quote from one of her rare interviews — ”Because there is this kind of exhaustion and bewilderment when you look at your work. . . . All you really have left is the thing you’re working on now. And so you’re much more thinly clothed. You’re like somebody out in a little shirt or something, which is just the work you’re doing now and the strange identification with everything you’ve done before. And this probably is why I don’t take any public role as a writer. Because I can’t see myself doing that except as a gigantic fraud” — and just leave it at that.

6. Because, worse yet, Munro is a pure short-story writer. And with short stories the challenge to reviewers is even more extreme. Is there a story in all of world literature whose appeal can survive the typical synopsis? (A chance meeting on a boardwalk in Yalta brings together a bored husband and a lady with a little dog. . . . A small town’s annual lottery is revealed to serve a rather surprising purpose. . . . A middle-aged Dubliner leaves a party and reflects on life and love. . . .) Oprah Winfrey will not touch story collections. Discussing them is so challenging, indeed, that one can almost forgive this Book Review’s former editor, Charles McGrath, for his recent comparison of young short-story writers to ”people who learn golf by never venturing onto a golf course but instead practicing at a driving range.” The real game being, by this analogy, the novel.

McGrath’s prejudice is shared by nearly all commercial publishers, for whom a story collection is, most frequently, the distasteful front-end write-off in a two-book deal whose back end is contractually forbidden to be another story collection. And yet, despite the short story’s Cinderella status, or maybe because of it, a high percentage of the most exciting fiction written in the last 25 years — the stuff I immediately mention if somebody asks me what’s terrific — has been short fiction. There’s the Great One herself, naturally. There’s also Lydia Davis, David Means, George Saunders, Lorrie Moore, Amy Hempel and the late Raymond Carver — all of them pure or nearly pure short-story writers — and then a larger group of writers who have achievements in multiple genres (John Updike, Joy Williams, David Foster Wallace, Joyce Carol Oates, Denis Johnson, Ann Beattie, William T. Vollmann, Tobias Wolff, Annie Proulx, Michael Chabon, Tom Drury, the late Andre Dubus) but who seem to me most at home, most undilutedly themselves, in their shorter work. There are also, to be sure, some very fine pure novelists. But when I close my eyes and think about literature in recent decades, I see a twilight landscape in which many of the most inviting lights, the sites that beckon me to return for a visit, are shed by particular short stories I’ve read.

I like stories because they leave the writer no place to hide. There’s no yakking your way out of trouble; I’m going to be reaching the last page in a matter of minutes, and if you’ve got nothing to say I’m going to know it. I like stories because they’re usually set in the present or in living memory; the genre seems to resist the historical impulse that makes so many contemporary novels feel fugitive or cadaverous. I like stories because it takes the best kind of talent to invent fresh characters and situations while telling the same story over and over. All fiction writers suffer from the condition of having nothing new to say, but story writers are the ones most abjectly prone to this condition. There is, again, no hiding. The craftiest old dogs, like Munro and William Trevor, don’t even try.

HERE’S the story that Munro keeps telling: A bright, sexually avid girl grows up in rural Ontario without much money, her mother is sickly or dead, her father is a schoolteacher whose second wife is problematic, and the girl, as soon as she can, escapes from the hinterland by way of a scholarship or some decisive self-interested act. She marries young, moves to British Columbia, raises kids, and is far from blameless in the breakup of her marriage. She may have success as an actress or a writer or a TV personality; she has romantic adventures. When, inevitably, she returns to Ontario, she finds the landscape of her youth unsettlingly altered. Although she was the one who abandoned the place, it’s a great blow to her narcissism that she isn’t warmly welcomed back — that the world of her youth, with its older-fashioned manners and mores, now sits in judgment on the modern choices she has made. Simply by trying to survive as a whole and independent person, she has incurred painful losses and dislocations; she has caused harm.

And that’s pretty much it. That’s the little stream that’s been feeding Munro’s work for better than 50 years. The same elements recur and recur like Clare Quilty. What makes Munro’s growth as an artist so crisply and breathtakingly visible — throughout the ”Selected Stories” and even more so in her three latest books — is precisely the familiarity of her materials. Look what she can do with nothing but her own small story; the more she returns to it, the more she finds.

This is not a golfer on a practice tee. This is a gymnast in a plain black leotard, alone on a bare floor, outperforming all the novelists with their flashy costumes and whips and elephants and tigers.

”The complexity of things — the things within things — just seems to be endless,” Munro told her interviewer. ”I mean nothing is easy, nothing is simple.”

SHE was stating the fundamental axiom of literature, the core of its appeal. And, for whatever reason — the fragmentation of my reading time, the distractions and atomizations of contemporary life or, perhaps, a genuine paucity of compelling novels — I find that when I’m in need of a hit of real writing, a good stiff drink of paradox and complexity, I’m likeliest to encounter it in short fiction. Besides ”Runaway,” the most compelling contemporary fiction I’ve read in recent months has been Wallace’s stories in ”Oblivion” and a stunner of a collection by the British writer Helen Simpson. Simpson’s book, a series of comic shrieks on the subject of modern motherhood, was published originally as ”Hey Yeah Right Get a Life” — a title you would think needed no improvement. But the book’s American packagers set to work improving it, and what did they come up with? ”Getting a Life.” Consider this dismal gerund the next time you hear an American publisher insisting that story collections never sell.

7. Munro’s short stories are even harder to review than other people’s short stories.

More than any writer since Chekhov, Munro strives for and achieves, in each of her stories, a gestaltlike completeness in the representation of a life. She always had a genius for developing and unpacking moments of epiphany. But it’s in the three collections since ”Selected Stories” (1996) that she’s taken the really big, world-class leap and become a master of suspense. The moments she’s pursuing now aren’t moments of realization; they’re moments of fateful, irrevocable, dramatic action. And what this means for the reader is you can’t even begin to guess at a story’s meaning until you’ve followed every twist; it’s always the last page or two that switches all lights on.

Meanwhile, as her narrative ambitions have grown, she’s become ever less interested in showing off. Her early work was full of big rhetoric, eccentric detail, arresting phrases. (Check out her 1977 story ”Royal Beatings.”) But as her stories have come to resemble classical tragedies in prose form, it’s not only as if she no longer has room for inessentials, it’s as if it would be actively jarring, mood-puncturing — an aesthetic and moral betrayal — for her writerly ego to intrude on the pure story.

Reading Munro puts me in that state of quiet reflection in which I think about my own life: about the decisions I’ve made, the things I’ve done and haven’t done, the kind of person I am, the prospect of death. She is one of the handful of writers, some living, most dead, whom I have in mind when I say that fiction is my religion. For as long as I’m immersed in a Munro story, I am according to an entirely make-believe character the kind of solemn respect and quiet rooting interest that I accord myself in my better moments as a human being.

But suspense and purity, which are a gift to the reader, present problems for the reviewer. Basically, ”Runaway” is so good that I don’t want to talk about it here. Quotation can’t do the book justice, and neither can synopsis. The way to do it justice is to read it.

In fulfillment of my reviewerly duties, I would like to offer, instead, this one-sentence teaser for the last story in Munro’s previous collection, ”Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage” (2001): A woman with early Alzheimer’s enters a care facility, and by the time her husband is allowed to visit her, after a 30-day adjustment period, she has found a ”boyfriend” among the other patients and shows no interest in the husband.

This is not a bad premise for a story. But what begins to make it distinctively Munrovian is that, years ago, back in the 1960’s and 1970’s, the husband, Grant, had affair after affair with other women. It’s only now, for the first time, that the old betrayer is being betrayed. And does Grant finally come to regret those affairs? Well, no, not at all. Indeed, what he remembers from that phase of his life is ”mainly a gigantic increase in well-being.” He never felt more alive than when he was cheating on the wife, Fiona. It tears him up, of course, to visit the facility now and to see Fiona and her ”boyfriend” so openly tender with each other and so indifferent to him. But he’s even more torn up when the boyfriend’s wife removes him from the facility and takes him home. Fiona is devastated, and Grant is devastated on her behalf.

And here is the trouble with a capsule summary of a Munro story. The trouble is I want to tell you what happens next. Which is that Grant goes to see the boyfriend’s wife to ask if she might take the boyfriend back to visit Fiona at the facility. And that it’s here that you realize that what you thought the story was about — all the pregnant stuff about Alzheimer’s and infidelity and late-blooming love — was actually just the setup: that the story’s great scene is between Grant and the boyfriend’s wife. And that the wife, in this scene, refuses to let her husband see Fiona. That her reasons are ostensibly practical but subterraneanly moral and spiteful.

And here my attempt at capsule summary breaks down altogether, because I can’t begin to suggest the greatness of the scene if you don’t have a particular, vivid sense of the two characters and how they speak and think. The wife, Marian, is narrower-minded than Grant. She has a perfect, spotless suburban house that she won’t be able to afford if her husband returns to the facility. This house, not romance, is what matters to her. She hasn’t had the same advantages, either economic or emotional, that Grant has had, and her obvious lack of privilege occasions a passage of classic Munrovian introspection as Grant drives back to his own house.

Their conversation had ”reminded him of conversations he’d had with people in his own family. His uncles, his relatives, probably even his mother, had thought the way Marian thought. They had believed that when other people did not think that way it was because they were kidding themselves — they had got too airy-fairy, or stupid, on account of their easy and protected lives or their education. They had lost touch with reality. Educated people, literary people, some rich people like Grant’s socialist in-laws had lost touch with reality. Due to an unmerited good fortune or an innate silliness. . . .

”What a jerk, she would be thinking now.

”Being up against a person like that made him feel hopeless, exasperated, finally almost desolate. Why? Because he couldn’t be sure of holding on to himself against that person? Because he was afraid that in the end they’d be right?”

I end this quotation unwillingly. I want to keep quoting, and not just little bits but whole passages, because it turns out that what my capsule summary requires, at a minimum, in order to do justice to the story — the ”things within things,” the interplay of class and morality, of desire and fidelity, of character and fate — is exactly what Munro herself has already written on the page. The only adequate summary of the text is the text itself.

Which leaves me with the simple instruction that I began with: Read Munro! Read Munro! Except that I must tell you — cannot not tell you, now that I’ve started — that when Grant arrives home after his unsuccessful appeal to Marian, there’s a message from Marian on his answering machine, inviting him to a dance at the Legion hall.

Also: that Grant has already been checking out Marian’s breasts and her skin and likening her, in his imagination, to a less than satisfying litchi: ”The flesh with its oddly artificial allure, its chemical taste and perfume, shallow over the extensive seed, the stone.”

Also: that, some hours later, while Grant is still reassessing Marian’s attractions, his telephone rings again and his machine picks up: ”Grant. This is Marian. I was down in the basement putting the wash in the dryer and I heard the phone and when I got upstairs whoever it was had hung up. So I just thought I ought to say I was here. If it was you and if you are even home.”

And this still isn’t the ending. The story is 49 pages long — the size of a whole life, in Munro’s hands — and another turn is coming. But look how many ”things within things” the author already has uncovered: Grant the loving husband, Grant the cheater, Grant the husband so loyal that he’s willing, in effect, to pimp for his wife, Grant the despiser of proper housewives, Grant the self-doubter who grants that proper housewives may be right to despise him. It’s Marian’s second phone call, however, that provides the true measure of Munro’s writerly character. To imagine this call, you can’t be too enraged with Marian’s moral strictures. Nor can you be too ashamed of Grant’s laxity. You have to forgive everybody and damn no one. Otherwise you’ll overlook the low probabilities, the odd chances, that crack a life wide open: the possibility, for example, that Marian in her loneliness might be attracted to a silly liberal man.

And this is just one story. There are stories in ”Runaway” that are even better than this one — bolder, bloodier, deeper, broader — and that I’ll be happy to synopsize as soon as Munro’s next book is published.

Or, but, wait, one tiny glimpse into ”Runaway”: What if the person offended by Grant’s liberality — by his godlessness, his self-indulgence, his vanity, his silliness — weren’t some unhappy stranger but Grant’s own child? A child whose judgment feels like the judgment of a whole culture, a whole country, that has lately taken to embracing absolutes?

What if the great gift you’ve given your child is personal freedom, and what if the child, when she turns 21, uses this gift to turn around and say to you: your freedom makes me sick, and so do you?

8. Hatred is entertaining. The great insight of media-age extremists. How else to explain the election of so many repellent zealots, the disintegration of political civility, the ascendancy of Fox News? First the fundamentalist bin Laden gives George Bush an enormous gift of hatred, then Bush compounds that hatred through his own fanaticism, and now one half of the country believes that Bush is crusading against the Evil One while the other half (and most of the world) believes that Bush is the Evil One. There’s hardly anybody who doesn’t hate somebody now, and nobody at all whom somebody doesn’t hate. Whenever I think about politics, my pulse rate jumps as if I’m reading the last chapter of an airport thriller, as if I’m watching Game Seven of a Sox-Yankees series. It’s like entertainment-as-nightmare-as-everyday-life.

Can a better kind of fiction save the world? There’s always some tiny hope (strange things do happen), but the answer is almost certainly no, it can’t. There is some reasonable chance, however, that it could save your soul. If you’re unhappy about the hatred that’s been unleashed in your heart, you might try imagining what it’s like to be the person who hates you; you might consider the possibility that you are, in fact, the Evil One yourself; and, if this is difficult to imagine, then you might try spending a few evenings with the most dubious of Canadians. Who, at the end of her classic story ”The Beggar Maid,” in which the heroine, Rose, catches sight of her ex-husband in an airport concourse, and the ex-husband makes a childish, hideous face at her, and Rose wonders ”How could anybody hate Rose so much, at the very moment when she was ready to come forward with her good will, her smiling confession of exhaustion, her air of diffident faith in civilized overtures?”

She is speaking to you and to me right here, right now.

Jonathan Franzen is the author of “The Corrections.”

Lifetime Achievement Award (2005)

A short story about Alice

Once upon a long time ago, before Time magazine called her one of the most influential people on the planet, Alice Munro, born in Ontario, worked as a clerk in the Vancouver Public Library. She wasn’t permitted to help library patrons find their books. A mother of three daughters, Munro occasionally found spare hours to scribble stories in the Kitsilano Library branch.

Then, in 1968, the same year Joni Mitchell released her first album, Alice Munro released her first book, Dance of the Happy Shades. Munro has been publishing her short stories in New Yorker ever since. Twice winner of the Giller Prize; three times the recipient of the Governor General’s Award for Fiction, Alice Munro is peerless as “the only living writer in the English language to have made a major career out of short fiction alone.” A reviewer for The Times (U.K.) has added, “reading her work it is difficult to remember why the novel was ever invented.”

Amid camera crews, dignitaries and well-wishers, Munro returned to the VPL in May to receive yet another award—the 11th annual Terasen Lifetime Achievement Award for an Outstanding Literary Career in British Columbia. “I guess I’ve come full circle,” she said. A new biography by Robert Thacker entitled Alice Munro: Writing her Lives (M&S $39.99) will be released in the fall. Meanwhile a plaque in Munro’s honour has been added to the Library’s Writers Walk. 0-7710-8514-1

[BCBW 2005]

Critical Responses

The 2001 Rea Award jurors Maureen Howard, James Salter and Edmund White wrote: “For many years the Canadian writer Alice Munro has astonished her readers with stories that are magical and wise. The magic is in her art as a storyteller, in her exquisitely modulated prose — lyrical, exacting, at time comical — which captures the lives of her charatcers, both women and men, attempting to understand their personal histories in the larger sweep of history. Munro’s configuration of time is Chekovian, supple in its bright flashes of insight, connection; shadowed in its strokes of disappointment, separation and loss. Long honored as a master of short fiction, Munro’s searching narrators often draw the reader to contemplate the devices of storytelling itself, the mysterious ways in which we distort reality, reconfigure the past to avoid or embrace revelation. Munro’s wisdom lies in her ability to portray the close-up, the self-dramatizing moment or limited vision then draw back for the complex and informing view. As one of her most endearing characters discovers, you can ‘look up from your life of the moment and feel the world crackling beyond the walls.’ In her art of the story, Alice Munro encourages us to reflect, to see our own time and place and perhaps to redeem, if not ourselves, at least our own stories in the larger setting of the world.”

Jonathan Franzen has described Alice Munro as, “the best fiction writer now working in North America.”

Cynthia Ozick has described Alice Munro as, “our Chekhov.”

Mona Simpson has described Alice Munro as, “the living writer most likely to be read in a hundred years.”

2009 Man Booker Prize: Press Release: Canadian short story writer is third writer to win prize

Alice Munro is today, 27 May 2009, announced as the winner of the third Man Booker International Prize.

The Man Booker International Prize, worth £60,000 to the winner, is awarded once every two years to a living author for a body of work that has contributed to an achievement in fiction on the world stage. It was first awarded to Ismail Kadaré in 2005 and then to Chinua Achebe in 2007.

Best known for her short stories, Munro is one of Canada’s most celebrated writers. On receiving the news of her win, she said, ‘I am totally amazed and delighted.’

The judging panel for the Man Booker International Prize 2009 is: Jane Smiley, writer; Amit Chaudhuri, writer, academic and musician; and writer, film script writer and essayist, Andrey Kurkov. The panel made the following comment on the winner:

‘Alice Munro is mostly known as a short story writer and yet she brings as much depth, wisdom and precision to every story as most novelists bring to a lifetime of novels. To read Alice Munro is to learn something every time that you never thought of before.’

Her latest collection of short stories, Too Much Happiness, will be published in October 2009. Alice Munro will receive the prize of £60,000 and a trophy at the Award Ceremony on Thursday 25 June at Trinity College, Dublin.

Too Much Happiness by Alice Munro (Douglas Gibson Books / M&S $32.99)

Review by W.P. Kinsella [BCBW 2009]

I’ll never forget what Alice Munro said to me the first time we met. She had come to Calgary to read. I purchased her book, I believe it was The Moons of Jupiter,” and thoroughly enjoyed it, but it had not occurred to me that most of the stories contained a lot of humour. The audience laughed heartily at the story Alice read, one I had read in all seriousness. I said to her after the reading, “It never occurred to me that your story was funny.”

Her reply was, “Bill, everything is funny.”

Her new collection Too Much Happiness contains ten delectable stories that are as good as anything she has written in her long career. The collection is vintage Munro in that many of the stories are novels, covering years and lifetimes, condensed to their tasty essence. The language as always is crisp and clear, like the tinkling of bells. Reading becomes a compulsion: one has to find out what is going to happen.

In ‘Deep-Holes,’ the character Sally has to deal with a son, who at age 9 falls into a deep hole and is rescued by his father. The boy becomes a strange, troubled, possibly insane adult, who disappears for years at a time. Here Munro comments on the difficulty of possessing specialized knowledge and how this era of the internet diminishes that knowledge. When her son was young they scoured books for information on obscure and isolated islands like Tristan da Cunha. Years later, wanting to brush up on those details, she thinks of the encyclopedia, but ends up on the internet where every imaginable fact about Tristan da Cunha is displayed. She no longer has secret knowledge, and feels a terrible disappointment.

In the opening story ‘Dimensions,’ Doree’s husband is in an institution for the criminally insane, having committed an unspeakable crime. Still, Doree visits him, unable to break the control he wielded over her. She listens to his manipulative ramblings and is tempted to accept his babble of other dimensions. She returns to reality literally with a crash, when she happens on an accident scene, and takes control of her own life by saving the life of a young accident victim. The language is striking: “A trickle of pink foam came out from under the boy’s head, near the ear. It did not look like blood at all, but like the stuff you skim off from strawberries when you’re making jam.”

The story ‘Fiction,’ my favorite in this exemplary collection, deals with the question of what is fact and what is fiction, and does a writer really know where a story comes from? Or, for that matter, what a story is really about. I’m reminded of Henry James protesting that The Turn of the Screw was merely an entertainment, negating the volumes of psycho babble written about the novel.

‘Fiction’ contains some wonderful humor that I didn’t miss. Here is Alice Munro describing a self-centred young author’s first book:

“How Are We to Live is the book’s title. A collection of short stories, not a novel. This in itself is a disappointment. It seems to diminish the book’s authority, making the author seem like somebody who is just hanging on to the gates of Literature, rather than safely settled inside.”

‘Free Radicals,’ the title a strong play on words,

is about a home invasion. The invader, young, dangerous and slightly insane enters the home of a widow living in a semi-rural area. The story sent me running to reread Flannery O’Connor’s ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find,’ the tale of an escaped convict and his pals executing a family in the rural South. In O’Connor’s story the sense of menace is palpable, in Munro’s it is muted. ‘Free Radicals’ is more about the widow, Nita, learning about herself and what she is capable of, as she concocts a story, trying to win the invader’s trust, about committing a murder herself. Only the deus ex machina ending is a little too pat, about the only soft spot in the whole collection.

The criminal shows Nita a photo of his family who he murdered earlier in the day. “. . . it was the younger woman who monopolized the picture. Distinct and monstrous in her bright muumuu, dark hair done up in a row of little curls along her forehead, cheeks sloping into her neck. And in spite of all that bulge of flesh an expression of some satisfaction and cunning.”

‘Child’s Play,’ the story of two very young girls at summer camp, explores the banality of evil, and how disturbing events put behind us will just never stay in their place.

The title story is vastly different from the other nine, but no less accomplished. The story describes the final journey of a real life person, Russian mathematical genius Sophia Kovalevsky, a woman who was far ahead of her time, and who was an inspiration to women of her time, and is still a model to aspiring scientists. Her genius was not fully acknowledged. “. . . they kissed her hand and presented her with speeches and flowers. . . But they had closed their doors when it came to giving her a job. They would no more think of that than of employing a learned chimpanzee.”

The Swedish were less discriminatory and she found employment is Stockholm. “The wives of Stockholm invited her into their houses. . . They praised her and showed her off. . . She might have been an oddity there, but she was an oddity that they approved of.”

One of the reasons I retired from fiction writing in my 60s, besides feeling that I had said most of what I wanted to say, was that I have seen so many elderly writers trading on their name and turning out pitiful parodies of their former greatness: Updike and Mailer immediately come to mind. Therefore, it was a relief to find that Munro has not lost a step, and that the quality of this collection matches anything she has written in her long career.

In my 40-some years on the CanLit scene, an industry rife with jealousies, feuds and petty backbiting, to which I have contributed my share, I have never heard anyone say anything unkind about Alice Munro, personally or professionally. When Alice wins a prize other writers and critics are not lined up to name ten books that should have won.

Now Alice Munro has won the prestigious Man Booker International Prize.

In my opinion she and Irish writer William Trevor are the world’s finest living short fiction writers, something the Nobel Prize people might well consider.

978-0-7710-6529-3

ALICE has not left the building

To honour Alice Munro’s acceptance of the $120,000 Man Booker International Prize in June—awarded for a body of work that has contributed to fiction on the world stage—a tribute to Alice Munro will open the 22nd Vancouver International Writers and Readers

Festival on October 18. Alice Munro is scheduled to attend.

Most artists end up imitating themselves. Their art degenerates into a copy of a copy of a copy. Alice Munro has remained a great artist for five decades because her stories are propelled by curiosity. Human nature (not moralism), is always the catalyst, and human nature has endless variations.

Life in Alice Munro’s fiction is frequently painful and disappointing—but the reflex of humour can be a crucial antidote, as W.P. Kinsella touches upon in his review [see above].

Now 78, Alice Munro raised her three daughters mostly in West Vancouver and Victoria, where her first husband Jim Munro, father of her children, still owns and operates Munro’s Books. She remains more of a West Coaster than most of her readers realize.

“I like the West Coast attitudes,” she told CBC Radio in 2004, “Winters [in B.C.] to me are sort of like a holiday. People are thinking about themselves. The way I grew up [in Ontario], people were thinking about duty.”

She has always been a writer. During her acceptance of Man Booker International Prize at Trinity College in Dublin, Munro recalled being seven years old, pacing in her backyard, trying to find a way to make Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid have a happy ending.

Her new collection of stories is called Too Much Happiness (Douglas Gibson Books, M&S $32.99). Simultaneously, there is a new edition of My Best Stories (Penguin $22), with an introduction by Margaret Atwood.

Alice Munro was born Alice Laidlaw in Wingham, Ontario on July 31, 1931. Her father was a farmer; her mother, a former teacher. When her mother developed Parkinson’s disease, Alice Laidlaw handled the brunt of domestic duties but nursed ambitions to become a writer.

“I think choosing to be a writer was a very reckless thing to do,” she told CBC’s Shelagh Rogers in 2004, “although I didn’t realize it. I was planning an historical novel in grade seven. It gave way to a Wuthering Heights novel I was writing all the way through high school.”

During her two years at the University of Western Ontario, she published her first short story in Folio, an undergraduate literary magazine, and met fellow student Jim Munro. They married in December of 1951 and moved to Vancouver where their two eldest daughters were born. Another daughter died of kidney failure on the day she was born.

In Vancouver Alice Munro befriended Margaret Laurence, another housewife who was learning to write, and she was inspired by the success of local novelist Ethel Wilson.

In Victoria, where a fourth daughter was born in 1966, she helped operate Munro’s Books (est. 1963), considered one of the finest independent bookstores in Canada.

In all, Alice Munro resided in Vancouver and Victoria for 22 years before her first marriage ended and she moved back to Ontario.

After separating from her husband in 1973, Munro became writer-in-residence at the University of Western Ontario in 1974. In 1975, she moved to Clinton, Ontario, in Huron County, with a former university friend, Gerald Fremlin, a geographer, partially in order to help look after his mother. Clinton is located approximately 35 kilometres from Wingham where she grew up. (The issue of Folio in which she had first published a short story also contained a story by Fremlin, who is slightly older than she.)

Alice Munro married Fremlin after she was divorced in 1976, the year she received her first honorary doctorate (having been unable to finish university due to lack of funds). They now divide their time between residences in Clinton in Ontario and Comox on Vancouver Island.

Encouraged by CBC Radio’s Robert Weaver since 1951, Alice Munro sold her first short story to Mayfair magazine in 1953. She has suggested she might have opted for the short story approach to fiction because she was balancing her duties as the mother of three children, but she also spent many of her formative years as writer trying to write a novel without success.

Alice Munro’s first short story collection, Dance of the Happy Shades (1968), received the Governor General’s Award for Fiction. Lives of Girls and Women (1971), which was marketed as a novel and received the Canadian Booksellers Award, was the basis for a Canadian movie of the same name that featured her daughter Jenny Munro as the heroine Del Jordan.

Recently Sarah Polley’s superb cinematic adaptation of Alice Munro’s story The Bear Came Over the Mountain, renamed Away from Her and starring Julie Christie and Gordon Pinsent, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

A frequent contributor to the New Yorker since 1976, Alice Munro became the eleventh recipient of the George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award for B.C. writing in 2005. She accepted the award, accompanied by her daughter, BCBW contributor Sheila Munro, at the Vancouver Public Library, where she once worked.

Alice Munro is only the third recipient of the new Man Booker International Prize. Part of her appeal is that her work is distinctly Canadian in a classic ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ mold. Typically, she told her Man Booker audience in Ireland that writing, for her, has amounted to “…always fooling around with what you find. . . .

This is what you want to do with your time—and people give you a prize for it.”

Munro doesn’t write whodunnits like Agatha Christie but she does reveal the mysteries of behaviour. Conventional thinking is never enough.

[BCBW 2009]

Munro wins Harbourfront Prize: Press Release (2013)

The International Festival of Authors announced today that this year’s recipient of the Harbourfront Festival Prize, worth $10,000, is Alice Munro. The perennial Nobel Prize contender will be honoured with the prize for her contributions to Canada’s literary community and the next generation of talent.

The prize will be awarded Nov. 2, the closing night of the festival, at a special tribute to Munro, who announced her retirement from writing in June. The evening will be hosted by Douglas Gibson, Munro’s publisher of nearly 40 years, and attended by the author’s colleagues, family, and other members of the literary community who will present readings from her work.

Munro was selected for the prize by a jury consisting of Q&Q publisher Alison Jones, Toronto Star books and visual arts editor Dianne Rinehart, and IFOA director Geoffrey E. Taylor.

[2013]

Nobel Prize for Literature: Press Release (2013)

from Writers Union of Canada

Alice Munro Wins the Nobel Prize for Literature / Writers’ Union founding member to receive her award in December

OCTOBER 10, 2013 – The Writers’ Union of Canada is thrilled at the news today of Alice Munro being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

“We are so proud of Alice,” said Dorris Heffron, Chair of the Writers’ Union. “We have all long admired and enjoyed her writing. We celebrate her as Canadian and a founding member of The Writers’ Union of Canada. Most of all we congratulate Alice Munro on this international recognition of her great contribution to literature worldwide.”

The Nobel Prize committee announced this morning that Alice Munro will receive a Nobel Medal, Nobel Diploma and a document confirming the Nobel Prize amount from King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden. The Nobel ceremony takes place December 10 in Stockholm, Sweden.

Alice Munro has written or contributed to twenty books in her storied career, and has won a host of other prizes before today, including two Giller Prize wins, a Governor General’s Award for Fiction, and the Trillium Prize. In an industry where the novel form can dominate attention, Alice Munro has inspired several generations of writers to expand on her work in the short story form. She is, as so many others have noted, the greatest living short story artist.

TWUC celebrates Alice Munro’s Novel Prize: Press Release (2013)

An Open Letter to TWUC members from the Chair of the Writers Union of Canada

“Alice Munro Nobel Laureate.” Surely millions of glasses were raised to that over Thanksgiving weekend. And not just in Canada! You can bet we thousands of TWUCers did. Alice was a founding member of TWUC. She was at the planning meetings along with Graeme Gibson, Margaret Atwood, Marian and Howard Engel and others. She attended the November 3rd, 1973 Ottawa meeting when TWUC was officially founded, with Margaret Laurence as Honourary Chair, Marian Engel elected Chair.

In 1980 when I attended my first TWUC meeting, I had the pleasure of sitting beside Alice. I have relatives still farming in ‘Munro country’. “That will be a lot of hard work,” said Alice in response to my remarks about revising my third novel. She has a strong work ethic. She does not write effortlessly.

This is what many people will be doing now… recalling times with Alice, the influence of her work. That’s my important point. Alice Munro as Nobel Laureate will have lasting influence. People at home and abroad will regard her and Canadian literature more highly. I had an email forwarded from a university professor of Canadian Studies in England, forecasting that the Canadian government will now appreciate Canadian writing more and restore more funding for it. Scoff as some may, there is plausibility in this and TWUC will work on it.

Alice has been a supportive member of The Writers’ Union of Canada for all its forty years. We thank her for that. As I said in our letter of congratulations to her, her work is much loved and so is she.

Dorris Heffron, Chair, The Writers’ Union of Canada

***

The Writers’ Trust later extended its heartfelt congratulations to short fiction genius Alice Munro, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature, by preparing a video tribute featuring authors Miriam Toews, Douglas Gibson, Alistair MacLeod, and more.

***

Nobel Prize ceremony shows Alice Munro is most popular recipient (2013)

Alice Munro’s editor since 1976, Doug Gibson, attended the Nobel Prize awards ceremony on December 10, 2013, at which Sweden’s King Carl XVI Gustaf presented the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature to “Alice Munro of Canada,” accepted on her behalf by her daughter Jenny Munro.

Peter Englund, the secretary of the Nobel Prize committee, said, “From my ten years of experience in handing out the Nobel Prize in Literature, I’ve never seen a prize so popular. She is the greatest short story writer alive in the world … impeccable.”

Here is Gibson’s eyewitness report that was initially printed in The National Post and reprinted by permission.

By Douglas Gibson

It is mid-afternoon in Stockholm but the darkening streets are full of men in formal white tie and tails escorting ladies in long dresses toward the Concert Hall. They look, my wife suggests, like a convention of conductors, but although an orchestra will be involved this afternoon, it is not a musical event. It is the formal ceremony for the presentation of the Nobel Prizes, and we are part of the hurrying throng because — as, literally, all the world knows — Alice Munro is this year’s winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It is hard for anyone outside Stockholm to realize what a hugely important event this is. Here, Nobel Prize Day is different. There is a Graduation Day feeling about the city streets. Already we have been startled — admittedly at the Nobel Museum (but did you know that there really is an actual Nobel Museum?) — by a loud trumpet fanfare at midday. But the public fascination in general is so strong for this local Oscar night that SVT (the Swedish equivalent of the CBC) has devoted one entire TV channel, the Nobel Channel, to the events throughout the day. They are all carefully recorded, minute by minute, up to the end, including the banquet in the evening. Cameras (carried by Swedish cameramen also wearing white-tie and tails) intrude on the diners, who give wise interviews. Every so often, of course, in the middle of the flow of mysterious Swedish we can make out the words “Alice Munro.”

To say Alice Munro is a popular Nobel choice is a huge understatement. She is everywhere here. SVT has run a documentary, in prime time, about her. I had a modest hand in this film, having taken the Swedish crew to the Boston Church near Milton, Ont. (where the earliest Laidlaws from Scotland are buried, and where I spoke learnedly about young Alice Laidlaw and her family). Later, I took them to Wingham (where the Alice Munro Literary Garden showed up well), and to Clinton (where Alice’s local friend, Rob Bundy, took them into Alice’s house, noting how seriously they composed themselves, before entering the actual room where Alice wrote). They even posed me for an interview high above the Maitland River near Goderich as we talked about the universal appeal of Alice’s work. The subtitles in Swedish look very impressive, suggesting that I was making some degree of sense. Best of all, the crew went on to Victoria and recorded a fine interview with Alice, and her daughter Sheila.

But that popular, prime-time broadcast (which has been repeated) was just one example of how omnipresent Alice Munro has been during the great flowing cocktail party of events this week.

Everything starts at the legendary Grand Hotel, which has its own “Nobel Desk,” where you pick up your itinerary and tickets for the week and stagger off, amazed. On Saturday, for example, the Nobel people organized an evening in Alice’s honour at the Swedish Academy, a “Nobel Conversation with Alice Munro.” It featured a 20-minute recorded interview where Alice (in Victoria) talks about her life and work, ending with a modest, grateful statement about how much winning this award means to her.

Present onstage at the Saturday event was Jenny Munro, Alice’s daughter, who has represented her mother with poise and charm throughout, and has made many friends. The constant demands on her and the constant round of interviews and other events confirm the wisdom of Alice’s regretful decision not to attend in person, and Jenny is a wonderful, gracious representative.