#199 What the Heckman

November 09th, 2017

REVIEW: Heckman’s Canadian Pacific: A Photographic Journey

by Ralph Beaumont, foreword by John Geiger

Mississauga, Ontario: The Credit Valley Railway Company, 2015.

$60.00 / 978-0-9784406-1-9

Reviewed by Walter Volovsek

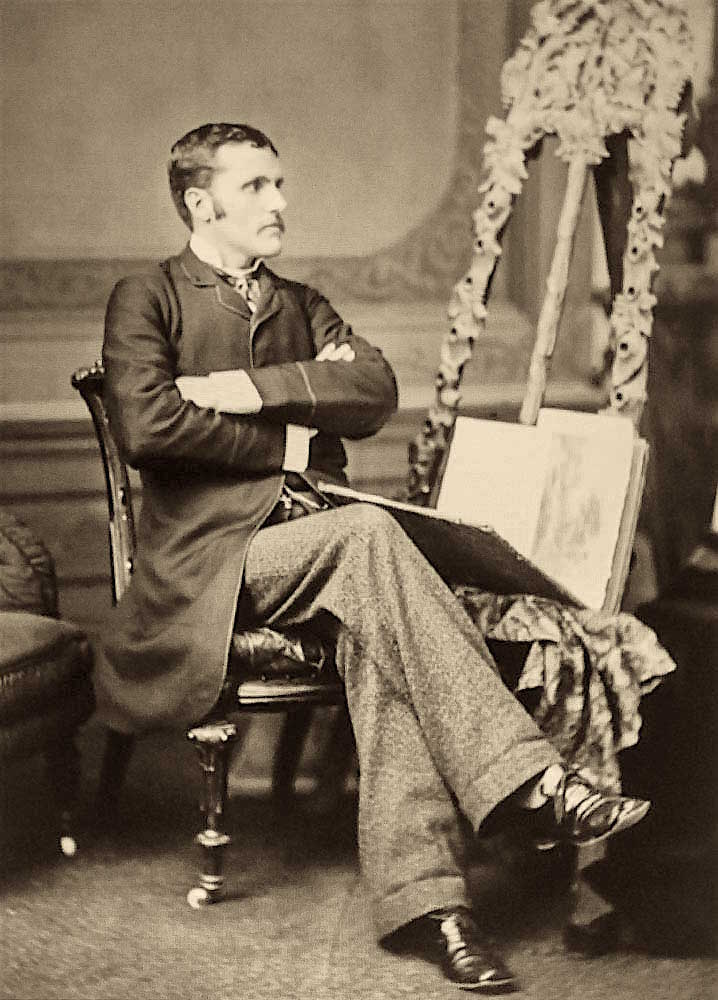

The Canadian Pacific Railway’s in-house photographer Joseph William Heckman (1854-1937) worked between Nova Scotia and Vancouver Island for three decades, photographing every aspect of the company’s extensive transportation network and amassing a record of over 4,000 images now housed in the CPR’s corporate archives.

The Canadian Pacific Railway’s in-house photographer Joseph William Heckman (1854-1937) worked between Nova Scotia and Vancouver Island for three decades, photographing every aspect of the company’s extensive transportation network and amassing a record of over 4,000 images now housed in the CPR’s corporate archives.

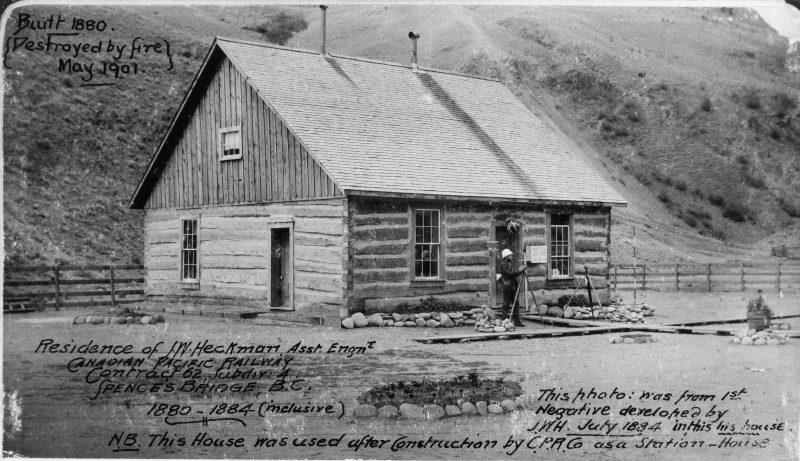

Heckman learned his craft in B.C. He set up a large format glass plate camera in a log cabin near Spence’s Bridge in the 1880s while working for Andrew Onderdonk, the contractor in charge of building the western section of the CPR between Port Moody and Eagle Pass in the Monashee Mountains.

As a CPR employee, Heckman had open access to the company’s handcars, cabooses, construction sites, branch lines, hotels, and subsidiaries. In Heckman’s Canadian Pacific: A Photographic Journey, Ralph Beaumont has selected 388 of Heckman’s best images.

Reviewer Walter Volovsek assesses the B.C. portion of what he calls Heckman’s “amazing record.” Volovsek concludes, “It is astonishing that Heckman could obtain such excellent results in an age of glass plate emulsions and in the absence of exposure meters.” — Ed.

*

Ralph Beaumont’s choice of subtitle — A Photographic Journey — reflects the meticulous planning and research that went into the production of his masterful Heckman’s Canadian Pacific.

But there’s more to the subtitle than that. “A Photographic Journey” is actually the title Heckman applied to his Field Books, in which he recorded exact details of his travels and photographic exposures. For the reader, the subtitle takes on a new meaning: a fascinating visual journey through a vast landscape of railway infrastructure that had been carved out fairly recently from a mostly empty – or at least depopulated — and rugged land.

Here is the Vancouver waterfront terminus for the CPR in 1899. It would be replaced in 1914. Joseph Heckman photo, CPR Archives.

Beaumont chooses images that show Heckman’s appreciation of CPR’s grandiose vision: first class hotels in the larger cities as well as in exotic mountain locations, the B.C. Lakes & River Service operations, the Empress series of ocean liners linking the continents.

The book is a feast for the eye. Heckman was quite conscious of photographic composition and balance, as becomes apparent in the images Beaumont has so carefully chosen.

Beaumont documents J.W. Heckman’s professional career beginning with his first work for the federal Department of Railways & Canals on Andrew Onderdonk’s contracts between 1880 and 1884. While working for Onderdonk he set up his operational base in a log cabin near Spences Bridge, and it was here that he took and developed his first photograph. In 1888 he entered the employ of the CPR directly in his old role as assistant engineer. For part of the next decade he held his position on a renewable contract basis.

His photographs of construction projects eventually caught the eye of higher management and in April 1898 he was reclassified as company photographer and took on the responsibility of documenting CPR infrastructure for maintenance and insurance purposes.

For such demanding work Heckman travelled in primitive style. He would travel by train to the nearest centre of his operations, taking with him his photographic equipment, glass plates, and processing chemicals, as well as a bench that could be fitted to the front of a handcar, to be provided by the local agent.

Thus he sat in front of the carriage, savouring the view ahead – much like the prime minister’s wife, Lady Agnes Macdonald, who spurned the comforts of a well-sprung carriage for a makeshift seat on the engine cowcatcher. Aside from his gear and lunch he kept an umbrella handy at all times.

He made his first journey to the West Kootenay in 1899 to document the company’s recent acquisition of the Columbia & Western Railway and the Trail smelter from F.A. Heinze. He returned in 1901 to record the newly constructed extension of the line from West Robson to Midway, and a decade later to photograph steel bridges that replaced the original timber trestles.[1]

The steamer Kootenay and Leland Hotel at Nakusp, B.C., September, 1899. Joseph Heckman photo, CPR Archives.

Close scrutiny of his 65 photographs from 1901 reveals that he took the train to the summits (Farron and Eholt), and allowed the handcar crew to coast down the grades. That technique puts his temporal progress at variance with the actual record that he produced at his home base in Montreal.

After assembling his prints, he conferred with his Field Book records for details and then reshuffled the photographs so they represented the rail lines in a geographical sequence. He developed numerical sequences to represent logical subdivisions, so that his record of over 4,000 images is kept in organized albums.

For me as a historian of the West Kootenay, the local Heckman record is invaluable. In 1901 he photographed the completed piers of the Columbia River bridge, then under construction at the abandoned site of Sproat’s Landing.

Building Columbia River Bridge between Castlegar and Sproats Landing (far shore), 1901. Joseph Heckman photo, CPR Archives. Image not in the book; obtained directly from Exporail, Heckman #2508a.

His photograph presents my first view of buildings associated with the steamer landing, and the farm of Thomas Sproat just slightly downstream, much as I had imagined them. They survived the 1894 flood, which surprised me.[2]

People are nearly always a feature in the Heckman images. Most commonly it is his propulsion crew and handcar; but often station agents and others were enticed into his viewscape by Heckman’s presence alone.

A rarer find, however, are photographs of workers caught in the act of building a structure. For obvious reasons, Heckman had to document the completed structures, and that was his primary objective. But at times he could not resist a work in progress, as in his image of replacement bridge construction over the Illecillewaet River near Glacier House.

Building stone bridge at Glacier Creek, source of the Illecillewaet River in Rogers Pass, July, 1899. Mt. Cheops behind. Heckman / Canadian Railway Museum. Image not in the book; obtained directly from Exporail, Heckman #1314.

It is astonishing that Heckman could obtain such excellent results in an age of glass plate emulsions and in the absence of exposure meters. As Beaumont points out, he employed a primitive calculation known as the Gilson Table, which employed parameters of Time, Weather, and Subject.

Heckman also had to consider film sensitivity and direction of illumination. The maintenance of a precise exposure record in his Field Books made him a master of his craft.

Beaumont does a fine job of documenting Heckman’s methodology in producing such an amazing record. The photographs are organized by railway subdivisions, with Beaumont providing a historical overview for each of them.

Beaumont balances out the coverage on all the lines, which leads to my only criticism of the work: the larger fraction of the photographs is sited east of the Rockies when the real engineering challenges for the railway were here in the mountains of Alberta and British Columbia.

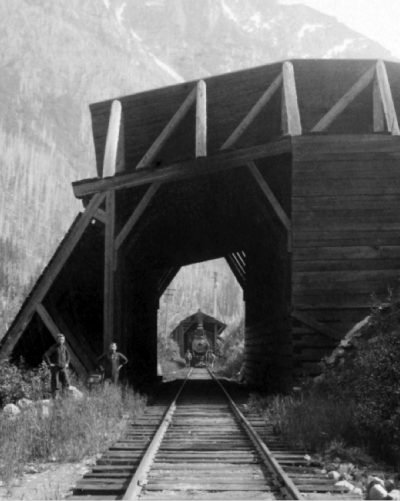

Structures like snow sheds are well covered, but I was anticipating more variety in Beaumont’s selection of images from the Kicking Horse or Rogers Pass areas. The vicinity of Glacier House always held a special fascination for me, with the famous Loops just beyond.

That, however, is a minor blemish in a monumental work.

Joseph William Heckman never married and left no progeny. But he left us an admirable legacy. His contribution to the process of envisioning our vast country when it was connected only by tenuous rail lines was gained by a great deal of skill and outstanding dedication.

Largely invisible are the many sacrifices and privations that must have accompanied him on the road. Indeed, Heckman makes me reflect on that other great traveller and recorder of past landscapes, David Thompson. I hope Heckman did not have to endure the struggles of financial burden and lost appreciation that weighed so heavily on Thompson during his last years.

Just as Thompson’s many achievements were championed half a century after his death by J.B. Tyrell, so Heckman’s legacy to Canadian history has been exposed by Ralph Beaumont.

We owe him our thanks and gratitude for bringing an obscure railway engineer to the prominence he so richly deserves.

*

After managing the biology labs at Selkirk College for 24 years, Walter O. Volovsek retired to a second voluntary career: developing walking and ski touring trails for the Castlegar community. Most of these are also presented to the user as conduits into the past by means of interpretive signage and related essays on his website www.trailsintime.org. This led to connections with descendants of important Castlegar pioneers, and in 2012 Walter self-published his biography of Castlegar founder Edward Mahon, The Green Necklace: The Vision Quest of Edward Mahon (Otmar Publishing, 2012). Mahon was also known for his legacy of parks and greenways in North Vancouver. Walter has also written a book on his trail-building efforts, Trails in Time: Reflections (Otmar, 2012), and has been commissioned to develop signs in key locations including Castlegar Millennium Park, Castlegar Spirit Square, and Brilliant Bridge Regional Park. Walter currently writes a history column for the Castlegar News. Like all Heckman enthusiasts, he would like to thank the help of Mylene Belanger, Archivist for Exporail: The Canadian Railway Museum, where the CPR Archives are now located.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] See the history panels for what is now the Columbia & Western Rail Trail: https://www.columbiaandwestern.ca/

[2] For Sproat’s Landing see: https://www.trailsintime.org/html/sproats

Leave a Reply