The under-heralded Kathy Page

Kathy Page has twice been longlisted for The Giller, most recently for The Two of Us.

May 04th, 2018

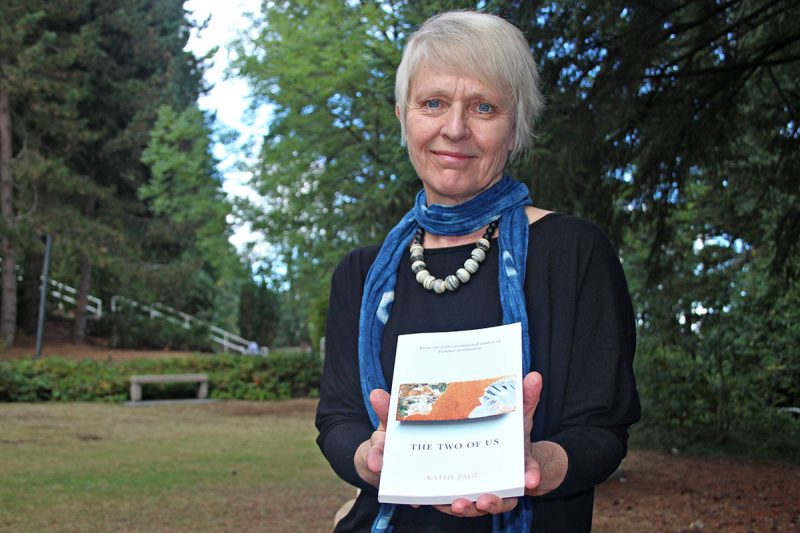

Kathy Page in her Saltspring Island studio. Billie Woods photo.

Page’s themes have been identified as loss, survival and transformation: “the magic by which a bad hand becomes a good chance.”

The Two of Us

by Kathy Page

Windsor, Ontario: Biblioasis, 2016.

$19.95 / 9781771960991

Reviewed by Paul Headrick

Kathy Page’s fiction has often been the bridesmaid, not the bride.

Kathy Page’s fiction has often been the bridesmaid, not the bride.

After she was longlisted for the Giller Prize in 2014 for her story collection, Paradise & Elsewhere, Page was longlisted for her follow-up collection, The Two of Us (Biblioasis) in 2016. The Story of My Face was longlisted for the Orange Prize in 2002. Alphabet was a Governor General’s Award finalist in 2005. The Find was shortlisted for the ReLit Award in 2011.

Born in England in 1958, Kathy Page studied English and creative writing at the universities of York and East Anglia, worked as a psychotherapist in England, and taught writing in the U.K. before coming to B.C. in 2001. Now chair of the Creative Writing and Journalism program at Vancouver Island University, she lives on Salt Spring Island with her husband and two children.

Herein reviewer Paul Headrick praises Page as “a master who seems to have tapped into ancient troubles bubbling up in our struggling world.” – Ed.

*

In “The House on Manor Close,” the opening story of this collection, a woman recalls her childhood with an older sister who was obsessed with birds: “I began to think that when she grew up she would become not an ornithologist but an actual bird.” Her fanciful speculation isn’t actually implausible, for in Page’s work we can be in the territory of Mavis Gallant at one moment and Franz Kafka or even Ovid the next. Her characters manage to inhabit the subtly psychological world of literary modernism while also belonging to the unpredictable, shifting landscapes of much older literary genres.

Page’s previous book, Paradise & Elsewhere (Biblioasis, 2014), an astonishing collection of contemporary folk-fairy tales, brought this ancient/modern element into relief, but it’s present as well in these stories, which are more realistic, at least on the surface.

Several that begin the collection are about elderly parents and their adult children. The parents need help that their offspring mostly fail to provide, burdened as they are by old, generosity-killing resentments. “Why are we like this,” asks the narrator of “Snowshill,” after a failed outing intended to cheer her enfeebled father and passive-aggressive mother. “Why can’t we all see how little time there is left?” The grudging reconciliation that follows seems dependent on shared self-deception.

In “The House on Manor Close” the mother exercises a weird tyranny, in part by feeding each of her three daughters differently, rewarding and punishing with dishes they like or despise. When her girls grow up and leave, alienated and angry, she and her husband indulge their passion for gardening, succeeding with plants as they never could with their girls: plants have potentials but not wills. The individual troubles here are entirely convincing while at the same time evoking the force of archetypal generational conflicts.

“Different Lips,” one of the strongest of these enthralling stories, is a variation on The Beauty and the Beast tale, which Page has explored before with startling effect in her novels. The character needing redemption in “Different Lips” is Beauty, not Beast. Jessica is a self-centred, damaged young woman who long has traded on her looks but who finally discovers herself desperate, out of money and friends. She travels across town to see an old lover whom she knows still yearns for her, and she hopes for sex, her only way of making connections.

A funny and cruel reversal greets her, no redemption at all, as her former lover’s lips are grotesquely swollen from an allergic reaction. After their wretched encounter, she struggles to make a last attempt to reach out to him and to save herself. The narrator pauses to describe the scene that Jessica passes:

The cheap restaurants and pubs nearby were filling up. People spilled out on to improvised terraces or else just leaned on walls, glass in hand. A few parents pushed slack-faced, sleeping children homewards, the older siblings, occupied with bright coloured drinks and ice creams, trailing behind.

The carefully chosen words — “cheap,” “improvised,” “slack-faced,” “trailing” — establish a continuity between the alienated main character and the failed world she inhabits, winning the reader’s recognition and deep assent in a way that contributes to the power of Page’s work.

The exceptions in these stories, the characters who are able to love, still feel a pull toward self-interest, but they choose to resist. In “The Right Thing to Say,” Don and Marla wait to discover whether she has inherited an incurable disease and to decide, if the news is bad, whether she will have an abortion. Don knows that he will also need to decide whether he is even capable of staying with Marla. The story echoes a fine Page novel, The Find (McArthur & Co., 2011), in which a couple faces a similar revelation.

In both cases, in the manner of the most gripping of folk tales, the tension-filled situations dramatize a choice that on some level we all must make, with the same ultimate consequences. (The story also gracefully alludes to Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants,” and it’s a mark of Page’s accomplishment that this move doesn’t seem at all audacious.) Don’s eventual response, which forms the resolution of “The Right Thing to Say,” is a brilliantly fitting surprise.

“Open Water,” the final story of The Two of Us and the longest, creates both the most realistically detailed world and the most impressive dramatization of the way that for Page realism and myth are one. Mitch, a swimming coach, gets a big break — out of nowhere, Tara, a prodigy. Mitch must proceed cautiously in order not to put off the girl’s parents, who are unenthusiastic about the extreme time commitment required by competitive swimming. He also needs to be cautious when Tara, on the verge of elite success, considers quitting swimming altogether.

Once again the story is about parents and children. In some ways Tara becomes closer to Mitch than to her mother and father, who are preoccupied with their other children, and with their own conflict — they separate when Tara is in her teens. We learn through flashback of Mitch’s childhood and his own mother and father, familiarly self-absorbed. “‘It’s tough having parents who ignore what you are,’” Mitch tells his wife when recounting his past.

The decision that Mitch helplessly awaits — Tara’s decision — isn’t as life-and-death as the impending news in “The Right Thing to Say,” but still it’s elemental, as the story consistently draws the reader’s attention back to the importance of water and the image of a person moving through it. “‘What the hell is it about?’” Tara’s mother asks Mitch of her daughter’s swimming life. “‘Being in the water,’” Mitch replies.

Earlier, Mitch recalls his lonely childhood at a boarding school that was precisely wrong for him, and the moment when he discovered the school’s unused swimming pool: “He remembers how his heart lifted, how he almost cried when he saw it. Just the sight of the water, the thought of being immersed.”

So Tara’s choice takes on that special Page quality: will she live on land or in water, choose realism or myth? How will Mitch, her proxy father, straddling both of these worlds, respond? With exquisite timing the answer confronts us with the immense stakes for Mitch and for all of Page’s characters in these stories, the works of a master who seems to have tapped into ancient troubles bubbling up in our struggling world.

*

Paul Headrick is the author of a novel, That Tune Clutches My Heart (Gaspereau Press, 2008; finalist for the BC Book Prize for Fiction), and a collection of short stories, The Doctrine of Affections (Freehand Books, 2010; finalist for the Alberta Book Award for Trade Fiction). He has also published a textbook, A Method for Writing Essays about Literature (Thomas Nelson, 2009; 3rd edition 2016). Paul has an M.A. in Creative Writing and a Ph.D. in English Literature. He taught creative writing for many years at Langara College and gave workshops at writers’ festivals from Denman Island to San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Recently he was a mentor for the graduate fiction workshop in The Writer’s Studio at SFU.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

MORE ON KATHY PAGE FROM ABCBOOKWORLD

Kathy Page was born and lived much of her life in London, England. She has taught fiction writing in universities in the UK, Finland and Estonia, and held residencies in schools and a variety of other institutions/ communities, including a fishing village and a men’s prison. In 2001, she and her family moved to Salt Spring Island. Page has also written extensively for radio and television and her short fiction is widely anthologised in the UK.

Page’s themes have been identified as loss, survival and transformation: “the magic by which a bad hand becomes a good chance.”

Her fifth novel, The Story of My Face, distributed in Canada by McArthur & Co., concerns a woman who reassesses her life while studying the origins of an unusual sect in Finland.

Alphabet (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2004) is about a convicted murderer in Thatcher’s Britain, barely out of his teens, who comes to terms with guilt and seeks possible redemption through newfound literacy. [See review]

Frankie Styne & the Silver Man (Methuen, 1992; Phoenix/Printorium 2008) is about the relationship between an obsessive loner who writes gruesome killer novels and his two new next-door neighbours, a new mother with a highly unusual infant named Jim. When the novelist Frank hatches a real-life plot, the lives of the mother Liz and her very strange child are transformed.

In Kathy Page’s seventh novel, and the first to be set in Canada, The Find (McArthur & Co $24.95), paleontologist Anna Silowski makes an extraordinary discovery in a remote part of British Columbia, but at the same time, the tensions below the surface of her successful career are exposed. She finds herself unexpectedly dependent on a high school drop-out, Scott Macleod, as she recruits him to help on the excavation of ‘the find’ and project teeters on the edge of disaster. “Her life would have been a lot simpler is she had not liked men, if she has been a nun, or gay. Or both.” The Find was partially inspired by the beautiful skeleton of an elasmosaur that hands from the ceiling of the Courtenay & District Museum.

Whereas Kathy Page’s story collection, Paradise & Elsewhere, delves into myth and the darker territory of parable and fable, The Two of Us contains stories about pairs, couples, dyads–mainly intense one-on-one relationships whether it’s a hairdresser and a client, a mother and her baby, or a girl and a fox. Her duos are all united by a primal desire for intimacy.

“My father’s passion for books, my mother’s habit of exaggeration, and the general craziness of our household are probably all behind my compulsion to write,” she recalls on her website. “As a child, I loved everything school had to offer: writing, science, art. I studied English Literature at university and graduated in 1979. Although I had won writing competitions as a child (a bizarre children’s cruise around the Adriatic, a bus trip around Europe), it was only after university, and very gradually, that I began to write seriously, supporting myself by means of temporary jobs and then a training as carpenter and joiner.”

CITY/TOWN: Salt Spring Island

DATE OF BIRTH: 8th April 1958

PLACE OF BIRTH: London, England

ARRIVAL IN CANADA: 2001

EMPLOYMENT OTHER THAN WRITING: university lecturer; writer in residence at a variety of institutions

AWARDS: The Traveller Writing Prize; Bridport Short Fiction Prize

BOOKS:

The Two of Us (Bibloasis 2016)

Paradise and Elsewhere (Bibloasis 2014) 18.95 978-1-927428-59-7 (trade paper)

In the Flesh: Twenty Writers Explore the Body (Brindle & Glass 2012. Co-editor.

The Find (McArthur @ Co. 2010)

Alphabet (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2004). 0 75381 861 2

The Story of My Face (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2002)

Frankie Styne and the Silver Man (Methuen, 1992; Phoenix/Printorium 2008)

As In Music (Methuen, 1990; Phoenix/Printorium 2008) — stories

Island Paradise (Methuen/Minerva, 1989)

The Unborn Dream of Clara Riley (Virago, 1987)

Back in the First Person (Virago, 1986)

[BCBW 2018] “Fiction”

Leave a Reply