The Tolstoy you didn’t know

November 26th, 2020

Leo Tolstoy considered his calendar books to be every bit as important as his novels.

Leo Tolstoy’s role as the world’s first global thinker is brought to light with the release of Tolstoy’s Words To Live By: Sequel to A Calendar of Wisdom (Ronsdale $24.95), a volume now made available for the first time in English, newly translated and edited by Peter Sekirin and Alan Twigg.

Tolstoy’s Words to Live By reproduces the inspiring quotes Tolstoy collected from more than forty philosophers such as Confucius, Jesus, Mohammad, Kant, Marcus Aurelius, Spinoza, Plato, Voltaire and the Talmud. This—his first compilation of once-suppressed teachings, originally published in 1903—led Tolstoy to produce three more collections of wisdom before his death in 1910.

One hundred years before the internet, Leo Tolstoy was an inventive moralist who went “viral” as the first intellectual to seek as much wisdom as possible, from as many great thinkers as possible, from as many centuries as possible. This was his grand achievement. Among those who were profoundly influenced by Tolstoy were a young Hindu lawyer named Mahatma Gandhi and a young preacher named Martin Luther King.

[Note: For the colour image, Sergey Prokudin-Gorksy took three photos of Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana in 1908, almost instantly, with three filters. He combined three black-and-white images, one with a red filter, one with a green filter, and one with a blue filter. The resulting three photographs were combined and projected together into one coloured picture.]

*

Leo Tolstoy’s primary focus during the last three decades of his life was not family, fame, finances or literature.

Leo Tolstoy’s primary focus during the last three decades of his life was not family, fame, finances or literature.

In the 1880s, he dropped his title of Count and requested his servants address him as plain Leo Nikolayevich. He increasingly adopted the attire of a peasant, worked with a scythe in the fields and took daily instructions from a shoemaker in order to learn a useful trade. Like a Russian Aesop, he wrote fables for the children of his serfs and he encouraged a literacy program at his Yasnaya Polyana estate.

He gave up hunting. He gave up smoking. He became a vegetarian and a teetotal. He attempted celibacy (much to the alarm and despair of his wife).

He stopped handling money as much as possible. In response to the famines of 1891 and 1898, Tolstoy and his children organized and administered soup kitchens, feeding hundreds of thousands who might have otherwise died. Increasingly, Tolstoy opted to distribute large portions of his own family’s wealth to charitable endeavors (much to the alarm and despair of his wife). Dozens of agricultural colonies, similar to the modern kibbutz, sprang up around Russia, organized by disciples who attempted to carry out Tolstoy’s views. Some landowners rescinded ownership of their vast properties in response to his teachings.

In support of the agrarian sect of “spirit wrestlers” known as the Doukobors—who burned their weapons in 1895 to protest universal military conscription—Tolstoy nominated the Doukhobors for the Nobel Peace Prize and raised funds from his wealthy friends. Eventually, he donated all royalties from his final novel, Resurrection, to help his son, Sergei, expedite and escort 2,300 Doukhobors by ship to Canada in 1899.

In support of Jewish families who suffered during the Kishinev pogrom in April of 1903—a major turning point in Jewish history—and in support of their migration to the United States, Tolstoy agreed to have three of his stories included in Help: An Anthology for Literature and Art (Warsaw, 1904) edited by Sholem Aleichem, the pen name of Solomon Rabinovich, the Yiddish short story writer and playwright who gave the world Fiddler on the Roof .

The fact that Tolstoy corresponded with major literary and political figures around the world, in different languages, kept him out of prison. Fearlessly, Leo Tolstoy became the most outspoken critic of the Russian Czar and he openly challenged the validity of the Russian government. He vigorously attacked the Russian Orthodox Church as false and corrupt. In keeping with the political beliefs of anarchists, Tolstoy resisted involvements with organizations. Although Tolstoy was appalled when some followers of his ideas became fanatics, he allowed all manner of beggars and lunatics to have access to him on his family estate (much to the alarm and despair of his wife).

Tolstoy completed his magnum opus among his religious works, The Kingdom of God is Within You, in 1893, accumulating some 13,000 manuscript pages about moral redemption and growth (more text than his three major novels combined). Banned from distribution in Russia, The Kingdom of God is Within You deeply impressed a young Hindu lawyer working in South Africa named Mohandas Mahātmā Karamchand Gandhi. “Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You overwhelmed me,” he wrote “It left an abiding impression on me. Before the independent thinking, profound morality, and the truthfulness of this book, all the books given me by Mr. Coates seemed to pale into insignificance.”

Inspired by Tolstoy’s writing, including The Law of Love, The Law of Violence, Gandhi proceeded to lead or initiate non-violent protests, strikes and other forms of peaceful resistance that resulted in the independence of India in 1947. Similarly, Tolstoy’s credo of non-violence had an enormous impact on a young preacher in the southern U.S. named Martin Luther King. Thereafter, in the wake of the Civil Rights movement that ended lynchings and segregation, similar, non-violent marches and protests in the 1960s led to the cessation of the Vietnam War. Few would realize their pacifism was linked to the “Burning of the Arms” by Doukhobors in 1895.

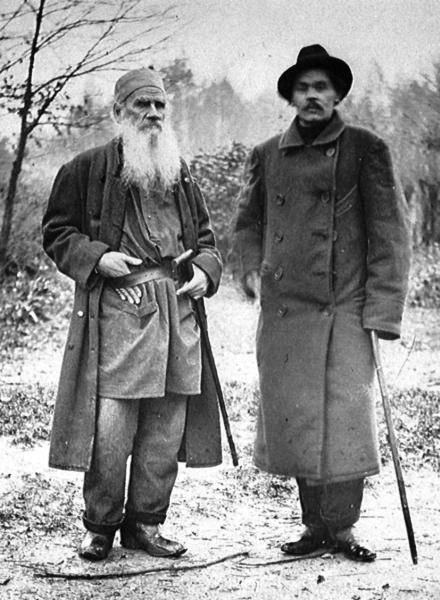

Leo Tolstoy with Maxim Gorky

To be remembered today as primarily a novelist—an entertainer—would have appalled Tolstoy. He was fluent in English, French and German, and he could read in Italian, Polish, Serbian and Czech. He also studied Greek and Old Church Slavonic, Latin, Ukrainian, Tatar, Turkish, Dutch, Bulgarian and Hebrew. He collaborated on a Russian version of Lao-Tze’s Tao Te Ching, he made himself familiar with the sages of Japan, he read Confucius as much as Aristotle. Gradually, Tolstoy’s patchwork belief system would have almost as much in common with Buddhism as Christianity.

Biographies of Tolstoy variously reveal that he sought solace and sustenance from great minds because he increasingly felt disappointment—and possibly shame—in himself. Tolstoy sought truth from literature in tormented hopes that he could be liberated by it. Particularly upsetting was his deteriorating relationship with his increasingly distraught wife.

And so Tolstoy compiled his collections of inspirational passages, the first of which forms the basis of Tolstoy’s Words To Live By. His private agonies and failings in no way diminish the validity of the wisdom he collected

THE AGONY & THE ECSTASY & THE HUMILIATION

In 1910, Tolstoy secretly and superstitiously left his home at Yasnaya Polyana in the middle of the night—at age 82 on October 28—in order to fulfill his dream of venturing into the world like the proverbial fool in the Tarot, unencumbered.

On that day Tolstoy wrote to Sophia, the mother of his 13 children, and described his life with her as unbearable, “I can’t live any longer in these conditions of luxury…” he added. “I thank you for your honourable 48 years of life with me.”

When Tolstoy had married her at age 35, Sophia Andreevna Behrs was eighteen. She would have 16 pregnancies (three miscarriages) while looking after the enormous household and handwriting versions of War and Peace seven times and possibly more versions of Anna Karenina.

In his memoir about his father, Tolstoy’s second-eldest son, Ilya, would recall, “She was almost like a child to him, little Sophia Behrs, and she remained so for a long time. The difference in age was never surmounted.”

Now the world’s most revered novelist was running away from home, fleeing from his wife whom he regarded with pity, as an unstable harridan. Accompanied only by his physician, Dr. Dusan Makovitsky, Tolstoy was knowingly leaving Sophia distraught and suicidal.

The departure was possibly hastened by shame. Just a few nights before, Tolstoy had been appalled to hear Sophia rifling through his study where he hid his private journal, most likely looking for any evidence to corroborate her unsubstantiated suspicion that her husband had a homosexual relationship with the rich and aristocratic Vladimir Chertkov, who served as Tolstoy’s editor, publisher, secretary and chief confidante.

Sophia constantly forced Leo to remove his photo of Chertkov from a table. After one of their quarrels, Sophia burst into her husband’s office and, seeing a photo of a hated “rival” in a glass frame on her husband’s desk, grabbed a revolver and shot into the image. Then she threw herself into a winter courtyard in her house-gown and ran down the streets shouting, “I’ll drown myself, hang myself, or shoot myself”. She came back home, cried, kissed the writer’s hands and asked for forgiveness. Such incidents were not uncommon.

A few days before Tolstoy had reiterated his wish, in a clearly-written statement sent to Chertkov, that his writing since 1881 must be declared public property. This would thwart his wife’s intentions to accept any lucrative offers from private publishers.

Fearing discovery, Tolstoy and his physician departed from the small Shchekino station at 6 a.m., to the Kozelsk station in Kaluga Province. It was only a short journey from there to the Optina Pustyn monastic retreat where Fyodor Dostoevsky had found solace in 1878 during the writing of The Brothers Karamazov. Tolstoy had sought spiritual advice at the hermitage on numerous visits.

From there they walked further north to the nearby Shamordino convent to visit Tolstoy’s only sister, Marya Nikolayevna Tolstoy (1830-1912), who had been a nun at Shamordino since 1891. Tolstoy was soon joined by his youngest daughter, Alexandra Lvovna Tolstaya (Sasha), who could be relied upon to take her father’s side in marital disputes. Meanwhile Tolstoy was relying on another daughter to remain at home and keep his wife off the scent.

In his rush to leave, Tolstoy had forgotten to bring copies of his collections of wisdom, The Circle of Reading and Thoughts of Wise Men, so he borrowed a copy of the former book from his sister. At Shamordino, he read the entry he’d made for October 28 in The Circle of Reading and saw it as a profound assessment for his present situation.

Along with a quotation from Marcus Aurelius, Tolstoy had added in his own words, “Pain is the necessary condition of our body, and suffering is the necessary condition of our spiritual life, from birth to death,” Tolstoy wrote in his diary on October 29, a few days before his death, “This suffering is necessary for me, and it is good for me.”

At around 3 a.m. on October 31, Tolstoy suddenly felt anxious that Sophia might find him at the monastery. He roused Dr. Makovitsky and Sasha, and the trio caught the first train headed south, towards the Caucasus. In a hasty letter to Chertkov he remarked he did not have any particular destination in mind, “Since it’s all the same to me where I am.” There was a hazy notion of escaping as far as Bulgaria, although Tolstoy was worried as to whether or not he’d be able to cross the frontier without a passport.

Tolstoy, Chertkov and Sasha had by this time adopted new pseudonyms for their messages: They were now Nikolayev, Batya and Frolova. Among the final requests he made to Chertkov, before leaving Shamordino after two days, was for his assistant, Bulgakov, to send copies of both A Circle of Reading and For Each Day, to his sister M.N. Tolstaya. “This is the most important thing,” he wrote.

Tolstoy had been prone to fainting spells for months and his memory was now severely flawed. With his daughter and doctor, he boarded a train bound for Rostov-on-Don at 8 a.m. on October 31, but by late afternoon Tolstoy had begun to shiver. Dr. Makovicky confirmed he had a high temperature. There was inflammation in both lungs.

It was decided to stop at the next station, whatever it was. This is how Leo Tolstoy ended his life at Astapovo, 140 miles south-east of Tula, in Ryazan Province. The station was relatively modern, having recently undergone a major expansion. Very quickly, the station master Ivan Ozolin provided Tolstoy with a bed in a large room of his nearby, red wooden house. Still fearful that his wife was pursuing him, Tolstoy gave orders to have the windows of the room covered after he thought he had seen a woman’s shape looking through the window pane.

Using his pseudonym Nikolayev, Tolstoy managed to write a terse message to Chertkov. It was to be their final correspondence: “Took ill yesterday. Passengers saw me leave train in weak condition. Afraid of publicity. Going on. Take measures. Keep me informed.”

Summoned by Sasha, Chertkov arrived at the tiny station on November 2 with his secretary Alexey Sergeyenko. More family members followed. Sophia was kept in the dark, mainly by her daughters, but as Tolstoy feared, his predicament quickly became front page news.

There was a frenzy of international publicity as newsmen started arriving with their whirring, hand-cranked Pathé cameras.

Sophia learned of his predicament and made her way to Astapovo in a first class railway car, in which she would remain for days, never allowed to see him, while Tolstoy had camphor injections and oxygen.

According to Sergei Tolstoy, death was constantly in his father’s thoughts. Tolstoy supposedly dictated a telegram to Sergei. “Tell my sons not to let their mother come, my heart is so weak that seeing her would mean death, though my health is better.” This incoherent message was read to Sophia as proof that she must not be allowed to visit the patient. Given that Sophia’s own children were willing to decide that she had driven their father on this escapade and she was the cause of his illness, it is not surprising Dr. Rastegaev diagnosed her to have “acute hysteria which may reach at times mental derangement.”

In his final letter, dictated in English on November 3, he wrote from the Astapovo railway station, “On my way to the place where I wished to be alone I was taken ill…”

Completely at odds with his intention to find solitude and peace, Tolstoy grew delusionary, amid a circus of agitation, and became weaker and weaker. The holyman Starets Varsonofy of the Optina Pustyn monastery also journeyed to Astapovo but Tolstoy’s handlers likewise prevented him from having access to Tolstoy, despite repeated requests. Sixty army officers arrived on November 6, ostensibly to respectfully retain order among the crowds of newspapermen with little else to do but drink vodka.

It was a demeaning exit for such a robust personality. He had long participated in heavy labour, often to help peasant widows, carrying manure, working with a primitive plough, chopping down trees and mowing with a scythe.

In 1886, Tolstoy had walked the 130 miles from Moscow to Yasnaya Polyana in five days. At age sixty-five, he had become an avid bicyclist, reading Letters on the Velocipede Game Considered as Physical Exercise and going to the bicycle racing track at Tula. As an old man, Tolstoy had loved horse riding in the woods at high speeds, on his favourite steed Delerio, and he had sometimes played tennis for three hours at a stretch.

Now his strength had been taken from him. When he realized he was going to die, Tolstoy asked to be brought the Bible and two cherished copies of his inspirational thoughts, A Circle of Reading and Thoughts for Wise Men for Every Day of the Year. The contents of these two volumes were triggered by the nascent collection now translated as Tolstoy’s Words to Live By.

THE ORIGINS OF TOLSTOY’S CALENDAR BOOKS

Tolstoy first mentioned his intention to produce a compendium of spiritual wisdom in a letter to Chertkov in 1885. Eight years later he commenced his habit of identifying and refining quotations for a book of advice for each day of the calendar. He did not feel obliged to remain strictly faithful to the original texts and over the years he added more of his own commentaries.

In the Preface to The Circle of Reading, he wrote, “If someone will translate this book into other languages, do this not from the language of the original, but from my text.” And in the Preface to The Way of Life (1910), he noted, “Most of these thoughts, both during the translation and the editing, have undergone many changes.”

Each anthology carried some common ideas but each also differed from the other in their material and the organization of the fragments. Some were systematic, others were less structured. All were intended to elevate humanity within what he called a “Reading Circle” because the reader would benefit from spiritual direction year-round.

The urgency and earnestness with which Tolstoy approached this ongoing project of self-education and enlightenment can be traced to two family deaths and two of his own near-fatal brushes with death due to illness.

The Tolstoys’ youngest child, Vanechka, was an exceptional boy who would surprise grown-ups by speaking with depth on abstract and spiritual matters. Admired by all, Vanechka was viewed by his father as a spiritual heir, someone who could be molded to embody the highest principles of Christian love and virtue.

“I somehow dreamed that Vanechka would continue after me the work of God,” Tolstoy wrote.

When Venechka died of scarlet fever in 1895, at age seven, his mother went nearly mad with grief. Ilya Tolstoy believed that if Vanechka had lived, his father’s life might have been very different, and that, regarding the death of Vanechka and the death of his father, there was an “unquestionably an intrinsic relation between the two events.”

Tolstoy resisted any displays of affection. His son, Ilya, alleged that “any display of tenderness was entirely alien to him.” But when Tolstoy’s fifth-born child, Masha, died of inflammation of the lungs, in November of 1906, her death shook him more noticeably than even the loss of Vanechka.

Masha had always been the person who could give him warmth, who could caress his hand and say affectionate things, and her father had responded to her very differently. “It was as if he became a different person with her,” Ilya wrote. “… And so her death deprived my father of the one source of warmth which, with advancing years, had become more and more necessary to him.”

Tolstoy himself fell seriously ill in June of 1901. Diagnosed with inflammation of the lungs and enteric fever, he was told to avoid another bitterly cold winter near Moscow. He reluctantly accepted the advice of his doctors and agreed to convalesce at a dacha [country house] outside Yalta, at Gaspra, a spa town in the Crimea.

Rather than insisting on travelling fourth class with fleas and cockroaches, as had become his custom, Tolstoy was sufficiently compliant to accept a first-class private compartment for the train journey on September 5. Although the Czar had ordered a press ban on reportage of his chief adversary’s movements, some 3,000 supporters greeted his arrival at the Kharkov station.

The dacha offered to him by Countess Anastasia Panina turned out to be a fairy-tale castle with two towers, built in the 1830s. Tolstoy had never experienced such luxury. To make life even more convivial, Anton Chekhov was only a telephone call away. Theirs was a fascinating friendship of mutual admiration but critical reserve.

Whereas Tolstoy never understood or appreciated the modern genius of the much younger man’s plays that showcased ambivalence, for his part, Chekhov found Tolstoy’s radicalism was over-wrought. Whereas Chekhov’s grandfather was a serf, Tolstoy remained an aristocrat from a family of gentry that could be traced through centuries.

Upon his first visit to Yasnaya Polyana, the low-born Chekhov had lost courage at the entrance to the estate and ordered his puzzled driver to turn back. Eventually one of Tolstoy’s daughters was smitten by the young medical doctor but Chekhov later married and he would die of tuberculosis, in 1904, at age 44.

While recuperating in the Crimea, Tolstoy also met with Maxim Gorky and befriended the scholarly Grand Duke Nikolay Mikhailovich who agreed to carry a personal letter from Tolstoy to the Czar addressed by Tolstoy as “Dear brother”.

Although Tolstoy professed to hate being served dinner by servants in white gloves, in the palatial setting he was eventually content as he recovered. For ten months Sophia was able to devotedly nurse her husband back to health, after his situation had appeared dire. Initially, he has been so weak with pneumonia that he could not turn over on his side by himself. According to his eldest son, he kept repeating a sentence he had read in a novel, “To die means to join the majority.” He also was fond of the words of an old peasant who’d said, “One should die in the summer—it’s easier to dig a grave.”

Arriving back home on June 27, 1902, Tolstoy was greeted by an even larger crowd at the station than the one at Kharkov. Although he would ignore his doctor’s advice not to spend any future winters at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy did agree to move his study upstairs to a well-lit room, next to his bedroom, with a balcony that caught the morning sun.

Soon his adversarial harangues against the Russian Orthodox church were as feisty as ever. In his ‘To the Clergy’ broadside, written in 1902 but not published until 1903, he lambasted the Church as “obsolete, irrational and immoral.”

Tolstoy was struck by a second bout of serious illness in December 1902. Bedridden at home, he slept beneath a wall calendar that offered daily sayings from various thinkers. Each day Tolstoy removed the sheets of the wall calendar. When the calendar came to the year’s end in December, Tolstoy wanted to devise a calendar himself with sayings from various sources.

And so he began compiling the text for Thoughts of Wise Men for Every Day, the first of several calendar books, providing wisdom for daily readings, now chiefly translated into English by Peter Sekirin as Tolstoy’s Words To Live By.

Tolstoy began work on his first calendar book on January 4, 1903 according to the diaries of his daughter, Maria Obolenskaya. His other daughter, Sofia Tolstaya, also wrote in her diary that he was healthy and choosing quotes for the calendar.

By late January of 1902, Tolstoy wrote to Chertkov to tell him that he had finished the book of quotations. By February, the manuscript was handed over for publication to the Mediator Publishing House and its editor-in-chief P. A. Boulanger.

Tolstoy continued to make changes up until very close to publication, working obsessively on the project. In July, he wrote to Boulanger asking him to revise the first entry: “… put this version of Francis and brother Leo on the calendar for January 1.” Tolstoy had found this excerpt in French clergyman and historian Charles Paul Marie Sabatier’s biography, The Life of Francis of Assisi, translated and published in Russian by Mediator Publishing.

By the end of August, the collection entitled Thoughts of Wise Men for Every Day was published. The origin of the title of the book remains unclear. In letters, both Tolstoy and Boulanger simply refer to it as a ‘calendar.’ Tolstoy calls it ‘the collection’ in his diary. Whether the title was given by Tolstoy or proposed by Boulanger – who used this expression in his letter to Tolstoy on August 13 – is unknown. In any case, this title was adopted by Tolstoy and was used by him to refer to the work with his correspondents.

On August 28, Tolstoy’s seventy-fifth birthday, the representatives of the editorial board of Mediator presented him with a printed copy of the book. Within a year, the book had appeared in multiple anonymous reprints. The initial publication by Mediator Publishing House, Thoughts of Wise Men For Every Day appeared without indicating sources, and the names of the authors were listed in the foreword.

We do not have any notebooks of Tolstoy, where he would have written his own sayings, included in Thoughts of Wise Men for Every Day. In 1911, a second edition by Mediator was published. Oddly, Thoughts of Wise Men for Every Day was not included in the early editions of Tolstoy’s collected works.

It is clear that Tolstoy saw the process of discovering and sharing the content of his calendar books as transformative, not only in spiritual matters, but also in terms of presenting the actual content. In his preface to The Circle of Reading, he wrote, “If someone will translate this book into other languages, do this not from the language of the original, but from my text.” In the preface to “The Way of Life, he wrote, “Most of these thoughts, both during the translation and the editing, has undergone many changes.”

For the rest of his life, Tolstoy considered his calendar books to be every bit as important as his novels, also surpassing the seriousness of his sophisticated, later works such as “Memoirs of a Madman,” “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” “The Devil” and “The Kreutzer Sonata.” Tolstoy believed his distillations of wisdom would be his greatest literary legacy and he wanted them to be made freely available to mankind.

DEATH

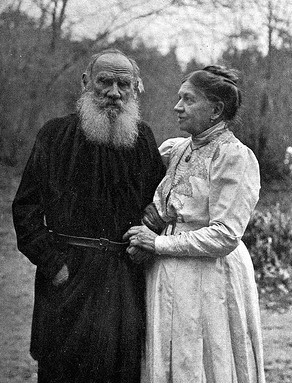

The final photo of Tolstoy and Sophia, 1910.

Contrary to almost every summary that has circulated about Tolstoy’s final days at Astapovo, Sophia did finally get admitted to see her husband on November 7. The details are provided in Sergei Tolstoy’s detailed memoir.

Back at Astapovo station, Countess Tolstoy held court with the newspaper correspondents who listened to her avidly. The family was dreadfully worried about what she might say. Prevented from seeing her husband, Sophia could have easily taken her revenge on them and voiced her suspicions about her husband’s relationship with Chertkov.

During the evening of November 6, Tolstoy was restless and moaning. “I’m afraid I’m dying,” he said. Suddenly he sat up and said, “Escape! I must escape!” The rest of his words were garbled. Around midnight his breathing was stertorous. The rattle in his throat grew louder. Finally, around 2 a.m., when Tolstoy was no longer able to recognize anyone, Sonja was granted an audience.

She stood at the foot of the bed. She calmly came closer, kissed him on the forehead. According to Sergei Tolstoy, who was biased against her, Sophia said, “Forgive me.” Leo Tolstoy was moaning. His lips were moistened with water. He lost consciousness at about 5 a.m. Life showed only in his breathing. Sophia came to the bed a second time, knelt down and whispered to him. Possibly hers was the last voice he heard.

Leo Tolstoy famously died at the Astapovo railway station soon afterwards, at 6:45 a.m., whereupon Dr. Dusan Makovitsky came forward and shut his eyes. According to Sergei, his father’s expression was calm and concentrated. It is worth bearing in mind that Sergei Tolstoy’s memoir as the eldest son was not published in Moscow until 1949.

The family received 3,000 telegrams. As Tolstoy had specified, he was buried at his birthplace, Yasnaya Polyana (Clear Glade), where he had spent 60 of his 82 years. His chosen gravesite was near a mound in the forest called “the place of the green wand,” so-named by his older brother Nikolai because, as boys, that had imagined it was a magical place where one would never be ill or die if they could find the green wand.

There were no speeches. It was said to be the first public burial of a Russian aristocrat without any church ritual. Everybody knelt together, except one solitary policeman, until someone shouted, “On your knees, policeman.” Chertkov did not attend.

WORDS TO LIVE BY

An ailing Tolstoy with his daughter Tatyana in Crimea, 1902

Tolstoy’s calendar books—from the Bible to George Eliot—have since been translated by a Canadian scholar of Ukrainian-Polish heritage, Peter Sekirin, co-editor of Tolstoy’s Words To Live By as well as the instigator of the project. Sekirin contacted Alan Twigg after he had contributed the foreword to Sekirin’s preceding book concerning the private life of Anton Chekhov.

Back in 1995, when Sekirin was teaching Russian in Ontario, one of his students asked him to recommend some titles for extra summer reading. Sekirin suggested some stories by Chekhov but wanted to add something by Tolstoy to the list.

Sekirin remembers the very hot day in July when he entered the Robarts Library in downtown Toronto, wondering to himself why, for heaven’s sake, he wasn’t out of town canoeing, his favourite sport since childhood.

Nearly everyone on the campus was away. It was cool and very quiet inside the enormous library. He proceeded to the 12th floor where he knew he could find Tolstoy’s Complete Works in 90 volumes.

Sekirin was deeply familiar with Tolstoy’s work. He was about halfway through reading the entirety of the canon. When he opened Volumes 39, 40, 41 and 42, he came across three of Tolstoy’s “Calendar books” for wise thoughts.

By coincidence, Sekirin noticed that the librarians in the Robarts Library had placed a new Russian edition of a single volume edition of Tolstoy’s collected wisdom that had been newly published in Russia in 1995. This “hot from the press” anthology boasted in Russian that its contents had been “suppressed and banned for many years by communists.”

Peter thought his student Don might be interested in reading it. Don was a bright and well-mannered boy, with British heritage, from rural Ontario, who had inexplicably taken Sekirin’s Russian course as an elective subject. Sekirin decided he’d like to give Don one of Tolstoy’s collections of world philosophy. That’s when he began to realize there was not any corresponding English edition for Tolstoy’s calendar books.

Sekirin double-checked the other shelves and asked the librarians for help before he knew for sure there were no English translations for these books.

Sekirin had little knowledge of Canadian publishing, and he didn’t realize that some larger American and British publishing houses had Canadian affiliates in his own city. He just knew that his favourite authors such as Charles Dickens, Henry Thoreau, Ernest Hemingway and, more recently, Stephen King, tended to be published in New York. It occurred to him that he might want to try translating a few pages and send them off to… well… New York.

Queries and samples were sent to eight editors; seven were seriously interested. In 1996, he signed a contract with Scribner Books for a Literary Work to be entitled The Calendar of Wisdom that would contain quotes for each day of the year, to be promoted as “a collection of Leo Tolstoy’s favorite inspirational quotations culled from sources reaching from the Bible to George Eliot.”

Born in Kiev, Ukraine, Sekirin grew up in Ukraine and attended university in Kiev. His maternal grandmother, Maria Korzeniowski, shared the same family surname as Joseph Conrad [Korzeniowski] and both originally came from the same Berdychiv (Polish: Berdyczów) region in the Ukraine.

Sekirin received his Master’s Degree in Linguistics and ESL (English) from the University of Kiev. He immigrated to Canada in 1991 after he met several Canadian-Polish professors at a teacher’s conference in Warsaw who invited him to Canada the year before.

In 2000, he completed his Ph.D. thesis on Dostoevsky and Tolstoy in Comparative Literature and Russian Literature at the University of Toronto where he remained as a Research Associate at the CREES (Centre for Russian and Eastern European Studies) until 2012.

Sekirin’s first-published book was The Dostoevsky Archive: Firsthand Accounts of the Novelist from Contemporaries’ Memoirs and Rare Periodicals in 1997. As well, he has translated and edited works by and about Anton Chekhov, most notably Memories of Chekhov: Accounts of the Writer from his Family, Friends and Contemporaries in 2011.

Peter Sekirin now lives in Aurora, Ontario, just north of Toronto, with his wife and two children, often hiking, canoeing and fishing in Northern Ontario and the Great Lakes region.

It’s interesting to note that Sekirin means carpenter in both Russian and Ukrainian.

THE CALENDAR BOOKS

Chekhov and Tolstoy, Yalta. 1901

In their order of publication in Tolstoy’s time, the calendar books were:

1. – Thoughts of Wise Men for Every Day of the Year (1904) / English edition, Tolstoy’s Words to Live By (Ronsdale Press, 2020). Translated and edited by Peter Sekirin and Alan Twigg. $24.95 (Cdn) 978-1-55380-629-5

The text herein has been translated in accordance with the original publication of The Mediator Publishing House in 1903, verified with a manuscript that was sent from Tolstoy’s estate, Yasnaya Polyana, for printing in February 1903. It is this version that is contained in Volume 40 of Tolstoy’s Collected Works (Rus. Мысли мудрых людей на каждый день, Mysli mudrykh liudei. Собраны Л. Н. Толстым). Tolstoy’s original version omitted the names of the philosophers. These, too, have been cited herein in keeping with the practice that Tolstoy adopted for his subsequent volumes. Thoughts of Wise Men had three editions during Tolstoy’s lifetime, each with a different sub-title: The Way of Life, Circle of Reading and A Wise Thought for Every Day. In this edited version, subject headings have been added by the editors in keeping with Tolstoy’s subsequent practice in later volumes. He wrote, “I have selected thoughts and grouped them into the following major topics: God, Intellect, Law, Love, Divine Nature of Mankind, Faith, Temptations, Word, Self-Sacrifice, Eternity, Good, Kindness, Unification of People (with God), Prayer, Freedom, Perfection, Work, etc.”

2. – Circle of Reading (1906, plus numerous editions) / English edition, A Calendar of Wisdom, Scribner, 1997, 2nd ed. 2017). Translated and edited by Peter Sekirin.

For this second collection, compiled from 1903 to 1906, Tolstoy accepted assistance from his children and their spouses, as well as his two assistants. Philosophers were credited with their quotations. It was a more extensive collection and it has a convoluted history because, as soon as it was published in 2006, Tolstoy began improving it, particularly during the winter of 1907-1908. It has been estimated he went through eight overall revisions by 1910. After it appeared in installments within publisher K. Slavnin’s periodical New Russia (Noavaia Rus) in 1908 and 1909, its publisher received a subpoena to appear in court. Slavnin managed to escape abroad but was sentenced in absentia to a year-and-a-half because it was determined that Tolstoy had rendered atheistic thoughts in a March 1st entry.

Most aphorisms from ancient thinkers were seemingly harmless enough, but the censors were increasingly leery of Tolstoy’s recurring emphasis on non-violence arising from his veneration of Jesus Christ. The alarmist sensitivity of the Censorship Committee was in deference to the difficulties recently faced by the Russian government to muster popular support for its campaign to wage the Russo-Japanese War, from February of 1904 to September of 1905, during which time the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan competed for control of Manchuria and Korea.

Tolstoy had already written extensively on the importance of identifying the best path for following the doctrine of Jesus—by disregarding the rhetoric of the Church and concentrating on what he considered to be the most important portion of the Gospels: The Sermon on the Mount. “I now read it frequently and often,” he wrote. “Nowhere does Jesus speak with greater solemnity, nowhere does he propound moral rules more definitely and practically, nor do those rules in any other form awaken more readily an echo in the human heart; nowhere else does he address himself to a larger multitude of the common people.”

Tolstoy then proceeded to explain the most important passage in The Bible, for him, was Matthew v. 38, 39. “Ye have heard that it hath been said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for the tooth: But I say unto, that ye resist not evil… But whosoever shall smite thee on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.” Resist not evil. Do not fight back. Turn the other cheek… Do not engage in war.

This was not a message that Russian authorities wanted to allow the charismatic and internationally-admired author to spread to the masses. The Russian fleet had recently been decimated; the conflict had lowered morale and public faith in the country’s political and military leadership. An extensively revised version from Odessa Leaflet Publishing appeared in January of 2010, while Tolstoy was still alive. It is likely this version that Tolstoy had with him when he died.

In the month after Tolstoy died in 2010, a third version was released by Mediator Publishing. Tolstoy’s death greatly enhanced the attention accorded to this work. While he was alive, Tolstoy’s reputation as an outspoken critic of both the Czar and the Russian Orthodox Church made him very dangerous to the powers-that-be who feared his influence. Newly deceased, his reputation was further enhanced by international press coverage. When the publisher of this memorial version, Ivan Gorbunov-Posadov, an ardent pacifist, decided he ought to disregard and disobey the Censorship Committee, the Russian authorities confiscated the print run and arrested Gorbunov-Posadov, who was already known as a radical who wrote anti-war poems. After brief court proceedings, Gorbunov-Posadov went to prison for a year, and many of Tolstoy’s entries for particular days in Circle of Reading had to be expunged before the book could be disseminated to the public again.

There was another version printed by Yasnaya Polyana Publishers in December of 1911 that provoked judicial intervention but publisher V. Maksimov was found not guilty. This cleared the way for a first edition from Sablin Publishing in Moscow in 1913. Twenty years later Academia Publishers of Moscow produced another small print run. Ultimately, a definitive version was published for posterity in Complete Works, Vol. 33-34 in 1932.

The first American version of Circle of Reading, published in 1997 by Scribners in New York and retitled A Calendar of Wisdom, enabled Peter Sekirin to negotiate separate versions internationally such as Calendario de la Sabiduria (Spain) and Tolstois Kalender Der Weisheit (Germany). Chinese versions appeared in Cantonese and Mandarin. Two editions appeared in South Korea. A publishing house in Jakarta produced Kalender Kata-Kata Bijak. And so on. Circle of Reading is contained in Volumes 41 and 42 of Tolstoy’s Complete Works (Rus. Круг чтения, Krug chteniia).

3. – The Way of Life (1910, 1911). Also known as The Path of Life, this lesser known compilation (Rus. Путь жизни, Put’ zhisni) had chapter headings such God and Love but it was not presented as a calendar book. Instead it was simply a collection of maxims. This non-fiction work of thirty chapters was prepared by Tolstoy during his final year of life. It was intended to serve as a shortened and simplified version of its predecessor, comprehensible to the least-educated readers, peasants and children. Tolstoy wrote, “To create a book for the masses, for millions of people . . . is incomparably more important and fruitful than to compose a novel of the kind which diverts some members of the wealthy classes for a short time, and then is quickly forgotten. The region of this art of the simplest, most accessible feeling is enormous, and it is as yet almost untouched.” A German edition (translated by E. Schmidt, A. Schikarvan) was published in Dresden in 1907 and Ivan Gorbunov-Posadov released a print run from Mediator Publishing in 1911.

4. – Tolstoy’s Weekly Readings / Re-published in English under the title Divine and Human and Other Stories (Zondervan Publishers, 2001). Translated and edited by Peter Sekirin.

Within his original A Calendar of Wisdom construct, Tolstoy prepared 52 weekly stories as diversions for the culmination of every week. These “Sunday school” stories were vignettes, three to ten pages in length, that usually corresponded to the week’s particular moral or philosophical topic. Tolstoy referred to them as his Sunday Reading Stories. Some were written by Tolstoy and others were adapted from writing by Plato, Buddha, Dostoevsky, Pascal, Leskov and Chekhov, etc. These stories told with simple, almost primitive writing were much admired by the Russian novelists Boris Pasternak and Andrei Solzhenitsyn.

– A.T.

*

EXCERPT

Tolstoy’s Words to Live By (Ronsdale Press $24.95) 978-1-55380-629-5

January 1 – Bliss

Brother Francis was walking with Brother Leo, from Perugia to Portiuncula, on a very cold winter’s day. Francis said, “Brother Leo, it would be nice if our brothers could give examples of holy love for all the world but—write this down—this would not be the complete fulfillment of joy.”

Shivering, they walked further. “Please write this down, Brother Leo,” Francis added, “that if our brothers could heal the sick, cast out demons, and make the blind see, even then, this would not be complete joy.”

A bit later, Francis said, “Write this, too. If we could speak all the languages of the earth and know every science, and if we could talk to the angels, and get all the treasures of the earth and understand all the mysteries of the stars, the birds, the fish, all mankind, the trees, the stones, and the waters; even then, this would not bring perfect joy.”

“Then how can we have perfect bliss?” Leo asked.

“We will know perfect bliss.” Francis answered, “when we arrive, cold, tired, and happy at our destination. We will knock at the door, and the pub keeper will scold us and refuse to open the door, and we shall say to ourselves, ‘God Himself told this man to say this.’ When we wait until the morning in the snow, slush, and wind, cold and drenched, without any feeling of malice for this man, we shall pray for him. Only then will we know perfect bliss.”

Leo Tolstoy

________________

- Perugia is the capital of the Umbria region in central Italy. Portiuncula is a small Catholic church located about 4 km from Assisi, in Umbria, where the Franciscan movement started. This parable attributed to Francis of Assisi was borrowed by Tolstoy from Mémoires de frère Léon sur la vie de saint François d’ Assise (Paris, 1880) by Paul Sabatier

Alternate cover mock-up with Russian illustration from the early 1900s.

Leave a Reply