#315 From props to hot properties

June 02nd, 2018

Life and Bronze: A Sculptor’s Journal

by Ruth Abernethy

Vancouver: Granville Island Publishing, 2016.

$60 / 9781926991733

Reviewed by Maria Tippett

*

Born in Lindsay, Ontario, in 1960, Ruth Abernethy started building theatre props at the age of 17. After studying at Malaspina College (now Vancouver Island University) in Nanaimo, she moved to Winnipeg, where by 1981 she was Head of Props at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre. Abernethy then worked for Tanya Moiseiwitsch at the Stratford Festival, and later across Canada for various theatre props departments. Her first bronze sculpting commission, in 1996, launched her solo art practice. Abernethy now divides her time between studios in Vancouver and Wellesley, Ontario

Born in Lindsay, Ontario, in 1960, Ruth Abernethy started building theatre props at the age of 17. After studying at Malaspina College (now Vancouver Island University) in Nanaimo, she moved to Winnipeg, where by 1981 she was Head of Props at the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre. Abernethy then worked for Tanya Moiseiwitsch at the Stratford Festival, and later across Canada for various theatre props departments. Her first bronze sculpting commission, in 1996, launched her solo art practice. Abernethy now divides her time between studios in Vancouver and Wellesley, Ontario

Reviewer Maria Tippett notes that “it is hard to exaggerate the extent to which Ruth Abernethy’s skills as a prop designer have informed her sculpture.” — Ed

*

Today contemporary sculpture can be anything. It can be made from a sheet of Plexiglas or COR-TEN steel, from raw flank steak or from a mound of sand. It can be assembled, dug, chipped, carved or produced on a 3-D computer.

It can raise social or political awareness or convey no message at all. It can be produced for public appreciation, or commissioned for a specific client or created solely for the aesthetic fulfillment of the sculptor.

And as for the viewer, he or she can see sculpture in the foyer of an office building, or in a remote field, or on the seashore, or in a sculpture park.

All of this is a far cry from the time when sculpture was the step-child of painting: an era when it was largely confined to the civic square or, if exhibited in an art gallery, was said to attract notice only if the viewer bumped into it while stepping back to view a painting.

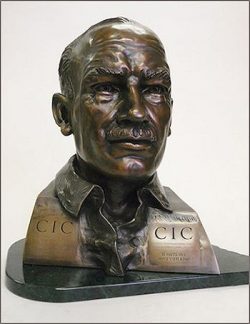

The sculptures illustrated in Ruth Abernethy’s Life and Bronze, A Sculptor’s Journal show us that there is still a demand for realistic subject matter, for traditional materials, and for the commemoration of notable people — especially, it seems, in small-town Ontario, in Toronto and in the nation’s capital.

In less than two decades, Abernethy has produced life-sized sculptures (and sometimes even larger than life) of musicians from Glenn Gould to Oscar Peterson; of statesmen from John A. Macdonald to W.L. Mackenzie King; as well as of scientists, poets, physicians, engineers, and theatre directors.

Abernethy has also created a few “abstract” sculptures like the exquisitely crafted three barbed wire baskets Christian fish, Judaic menorah, and Islamic minarets created for the Sculpture in Context exhibition in Dublin, Ireland. Her work has been variously commissioned by private patrons, by government agencies, or by cultural foundations. Sometimes the artist won a “Call to Artists” competition. All of Abernethy’s sculptures required painstaking research: by reading a subject’s letters, or diary or biography; by studying photographs; by interviewing surviving friends and relatives; or by drawing on her own memory of the subject.

Ruth Abernethy came to sculpture through the theatre. Trained as a theatre technician at Malaspina College in Nanaimo (now Vancouver Island University), Abernethy began her career working in the props department of the Manitoba Theatre Centre then, moving back to her native Ontario, at Toronto’s Tarragon Theatre and Stratford’s Festival. Loving “the engineering and architecture of structures” and “exploring new materials” (p. 154), Abernethy made theatrical “props” ranging from an eight-foot-tall head of Julius Caesar, to human-scale masks and architectural models. And then, in 1996, at the age of thirty-six, she made her first bronze figures for the Stratford Festival. Her career as a sculptor, largely in bronze, was thus launched.

Life and Bronze, A Sculptor’s Journal supplies no independent commentary on the artist’s work, but some themes are inescapable. Thus, it is hard to exaggerate the extent to which Ruth Abernethy’s skills as a prop designer have informed her sculpture. Likewise, her bulky and frequently sagging figures speak to a lack of the sort of training in anatomy that would have been acquired from drawing or modelling the life figure at art school. While Abernethy’s stated goal is to create a realistic likeness of her subject, the result often verges on caricature. And appropriate props duly claim an important role in her work: Oscar Peterson sits at a piano, Glen Gould rests on a park bench and Queen Elizabeth the Second sits on the edge of a throne.

Other figures in Abernethy’s oeuvre strive for dramatic expression. For example, she seeks to capture the moment when First World War poet John McCrae “completed writing the verse” for his memorable poem, In Flanders Fields (p. 121). Dramatic representation of a theme of anticipation and promise are also suggested by depicting younger versions of the Queen and of Canada’s first two prime ministers, John A. Macdonald and Alexander Mackenzie.

Reactions will vary. Some readers of Life and Bronze, A Sculptor’s Journal would have appreciated a list of the artist’s sculptures, with completion dates and mediums. As a cultural historian, I would have liked to have known more about the problems associated with winning public and private sculpture commissions, and then any difficulties that arose while fulfilling them. Was a particular work paid for by public subscription or by one donor? Was the artist’s fee always paid on time? And what about the physical challenge of working on such a large scale? Ruth Abernethy writes that she employed various assistants but she does not specify their role. Of course, it is a success story that is celebrated here.

As the need for the commemorative sculpture will undoubtedly continue, Ruth Abernethy will never be without work; and likewise, Life and Bronze: A Sculptor’s Journal will not be the last word on this artist’s unfinished oeuvre of fine sculptures.

*

Maria Tippett spent the formative years of her academic career as a sessional lecturer at Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the Emily Carr College of Art and Design. Following her year as Robarts professor of Canadian studies at York University (1986–7), she lectured in South America, Europe, and Asia and curated exhibitions. In 1991, she returned to academe, becoming a member of the Faculty of History at Cambridge University and a senior research fellow and tutor at Churchill College, also at Cambridge. Since her formal retirement in 2004, she has written four books, including the recently published Sculpture in Canada: A History (Douglas & McIntyre, 2017). Among many awards, in 1980 she won the Sir John A. Macdonald Prize for her path-breaking Emily Carr: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1979).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply