Stroke and distance

“I continued to view my condition as a nightmare in which I was a reluctant participant," says Ron Smith.

November 27th, 2016

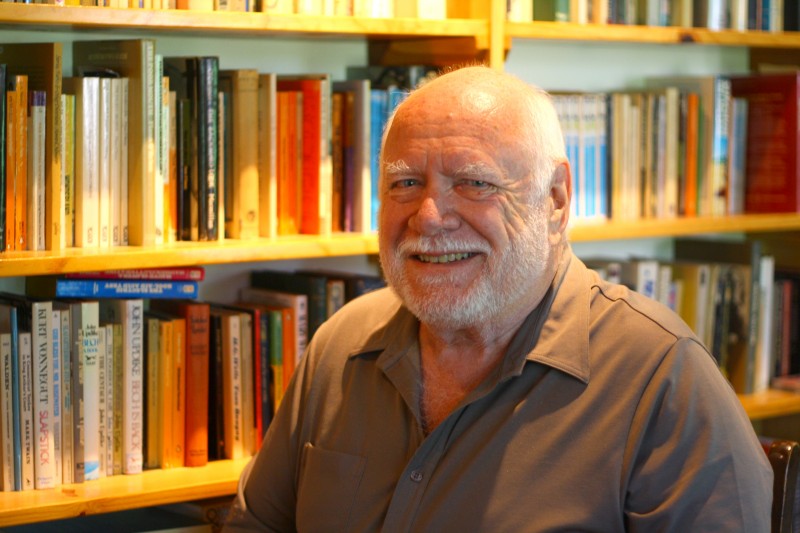

Pat Smith was essential for the four-year recovery process of her husband, Ron Smith.

Using the index finger of his left hand, he began typing The Defiant Mind eight months after a massive ischemic stroke.

by Mark Forsythe

Ron Smith, the founder of Oolichan Books, thinks the word “stroke” is far too light to describe a brain that has been “attacked” or “carpet bombed.” In his case it meant paralysis on the right side of his body, depression, constant fatigue and untold tears.

At first he couldn’t communicate; his voice sounding like he was, “chewing on a mouthful of rubber bands.” He describes feeling absent from his own body, becoming “a shadow being” like something his archaeologist daughter might dig up.

Family and friends figure prominently in his memoir, The Defiant Mind: Living Inside A Stroke (Ronsdale Press $22.95). The power of being told you’re going to get better, and that you’re loved, cannot be overstated. They helped Smith feel human again.

Like many people, he shrugged off the early warning signs. Light headedness, vertigo, a collapse on the golf course and a growing weakness on one side of his body were self-diagnosed as the flu.

His wife Pat thought otherwise and took him to Nanaimo Regional Hospital where a doctor insisted that he check in for observation. This saved his life.

While waiting in ER, he suffered a full attack.

“I felt as though I were trapped or lost at the heart of a maze. Bewildered, I couldn’t see a way out. And I kept spiralling down, down to a place I knew I didn’t want to go to. It was so dark and crushing and lonely.”

While lying in a hospital room beside a noisy and demanding patient, Smith used his memory to escape, and began to reconstruct his personal identity that he worried was slipping away. Smith remembered much loved books, music and paintings. Banned from solid foods until he could swallow safely, his hunger triggered memories of travels to Spain, France and Morocco as a young man on a puny budget.

“Who we are and what we do is fundamentally a function of memory,” he writes.

While physical needs were met by health care professionals, his mental needs were not. They didn’t know what was going on inside his head.

No one knew what caused the stroke or if it would happen again. Smith felt inner chaos (extreme sensitivity to sound and light), pain and spasticity, fear (am I dying?), anxieties (will I be disabled?) and loneliness.

“…my body felt weighed down, like a tree branch bent low to the ground after a heavy snowfall, and my brain was in free fall, rapidly losing touch with thoughts and images that connected me to the familiar. How I longed to kick my way through a pile of leaves and stare up through the bony shapes of maple and alder trees at the winter sky.”

In The Defiant Mind, Ron Smith explores new research around memory and brain plasticity which is the brain’s power to regenerate pathways. He works hard at multiple therapies: exercise, meditation, massage, acupuncture, personal training and swimming where, “everything stops hurting.”

He also imagines walking the streets of London and Rome or the sands of Long Beach with Pat. His ability to hold a book, turn the pages and read eventually returns. “What a feast for a reawakening mind.”

Smith worries that too often stroke victims are abandoned by health professionals and he tells the story of a patient who couldn’t speak, but could tap out messages in Morse Code. Each patient’s experience is unique. There is no template for treatment.

Smith does value the care health professionals provided, but laments a huge gap in knowledge and understanding of what individuals are actually experiencing.

Today Ron Smith uses a cane and walker amid the trees at his Nanoose Bay home. He hopes to regain at least 80% of his former mobility, but in hindsight says he should have taken note of symptoms sooner and dialed 911:

“Had I used common sense,” he says, “I could have prevented myself years of unnecessary grief.”

A stroke is the leading cause of disability in North America.

978-1-55380-480-2

Mark Forsythe is co-author of The BC Almanac Book of Greatest British Columbians.

****

INTERVIEW

“What is a stroke?” In The Defiant Mind: Living Inside a Stroke, Ron Smith explores that question in depth as a stroke survivor for stroke survivors and for caregivers who are vital to the process of recuperation. Both often feel hampered and harried by concern and confusion. For medical professionals, the book offers insights into the workings of the brain, the power of the brain to heal, critiques of conventional limits imposed on therapy and suggestions for ways to improve care. This interview with Ron Smith first appeared online via the Stroke Recovery Association of BC. It reprinted here by permission.

QUESTION: How long ago did you have your stroke?

RON SMITH: I had my stroke on November 19, 2012, a day, as a stroke survivor, you never forget and your family never forgets. So many people are affected.

Q: What was your first thought when you were told you had suffered a stroke?

RS: Disbelief. I was in denial from the onset. I had what the emergency doctor referred to as a stuttering stroke. I think what he meant by this is that I had a series of smaller strokes before the bigger stroke hit. After the major event, which happened in the waiting room of emergency, I wasn’t having thoughts that registered. I inhabited a place I can only describe as ‘limbo’.

Q: What main challenges did you face and how did you overcome them?

RS:Paralysis. My right side was paralyzed. This was frightening. Initially my speech was impaired but this righted itself fairly quickly. With a little effort, people could understand me after a few days. Perhaps the biggest problem was that I didn’t feel like I belonged to the world anymore even though I felt my cognitive powers were still intact. The combination of loss of physical and emotional control and the sense of no longer belonging to the everyday world resulted in severe depression. After a week and a half I decided I could either wallow in self-pity or take action. In combination with physical therapy I decided to meditate. Eventually I was able to travel to the injured parts of my body. I also decided, very deliberately, that I needed to take a positive and proactive approach to my recovery. I have never stopped therapy. I have read as much as possible by other stroke survivors and a number of books on the brain, brain plasticity and new forms of therapy. I also used memory to find my way back to myself, to the person I had been. Patience is vital to the stroke survivor’s well-being because recovery can be very slow.

Q: Please tell us about your writing.

RS: Before my stroke I taught English and Creative Writing at the university level; I owned a publishing company; and I wrote and published books (poetry, fiction, non-fiction and children’s books). I was lucky, writing was my life and was a vocation to which I could return with relative ease. Too many stroke survivors can’t return to what they did in their former life; to something they loved doing. Eight months after my stroke I decided to write about my stroke experience. My only handicap was that I had lost the use of my right hand. I typed my book, The Defiant Mind: Living Inside a Stroke, over 300 pages, with the index finger on my left hand.

RS:The Defiant Mind is a book about the wonder that is the human brain, both before it has been damaged and after, when it’s struggling to pick up the pieces and make some sense of the muddle it has become ? the jigsaw puzzle of scattered recollections, unidentifiable objects, inexplicable emotions, impenetrable ideas. I hoped the book would be useful to other stroke survivors, care-givers and therapists. I also hoped it would help the general public understand what a stroke is, at least from my perspective. I felt that most people simply didn’t understand stroke; I certainly didn’t before my brain attack. I think most people see stroke as heart attack’s lesser cousin. But if my book doesn’t achieve these goals at least it will have been another form of therapy for me; another way to explore my own experience. Writing also puts my brain to work, which seems essential to my recovery. I still write poems and I’m now plotting a novel that has been nagging me for years.

Q: How did having a stroke affect your daily activities?

RS: As with most stroke survivors, in some ways my life has changed dramatically, in other ways not much. I’m still handicapped so there are many activities I can no longer do. I used to play golf. I no longer can, although recently I have gone with a friend to try to hit balls. Most of our time is spent sitting on a bench talking about Tai Chi and various other exercises that might help me. He’s a martial arts expert. Being in an old familiar environment is simply good for my spirit. I tire more easily than I used to; I take a nap at least once a day. I can’t work in the garden which I used to love doing, my hands in soil. But I still enjoy the plants, so I sit amongst them and the trees. And there are a few little things like tying my shoes I can’t do, but my ultimate goal is to care for myself. I’m determined to do as much possible for myself. Yes, I get frustrated but then I think about how far I’ve come. At least three to four times a week I go to a local pool. I can exercise in water with abandon. I love the water’s primal feel and wish it had been a part of my therapy from the beginning. Otherwise I try to do as many of the things I used to do, with a little less rush.

Q: If there’s a message you could send others who are recovering from a stroke, what would you say to them?

RS: “Expect full recovery,” Jill Bolte Taylor advises. I agree. I have experienced new neuro pathways forming, literally. There is no time limit on changes. They may be slow, very slow, but they happen. As the Irish proverb says, “When God made time, He made plenty of it.”

Q: Are there any ways in which your life is better now?

RS: In some ways I feel I’m more productive now than I was before. As hackneyed as this sounds, I appreciate life more than I did before. I’m happy to have witnessed the birth of a new grandson; this was pretty special.

That’s quite a battle you’ve fought, Ron. I’m looking forward to hearing your talk in the New Year at the Sidney Library.

Wishing you a joyful Christmas, Dan

Great to hear your story Ron and to understand more about your life after stroke.

Sarah Belson

World Stroke Organisation

Keep on keeping on, Ron!! Life might have changed, but it isn’t over, there are still books to publish, still walks to take and still loving hands to hold.

I call my cane “my upstanding friend”. Couldn’t handle a walker, got rid of it early on because it felt to me as if the bugger was fighting me every inch of the way.

Thanks for your note, Anne. Much appreciated. I assume you’ve had a stroke? I didn’t know. Sorry to hear this news. Yes, getting rid of the wheelchair and then the walker made a huge difference to my life, especially after I was told that neither was possible. Life is good!