#223 Starvation Cove & Terror Bay

December 18th, 2017

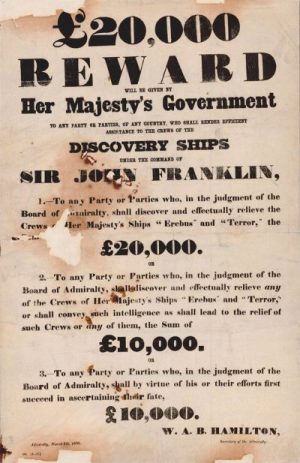

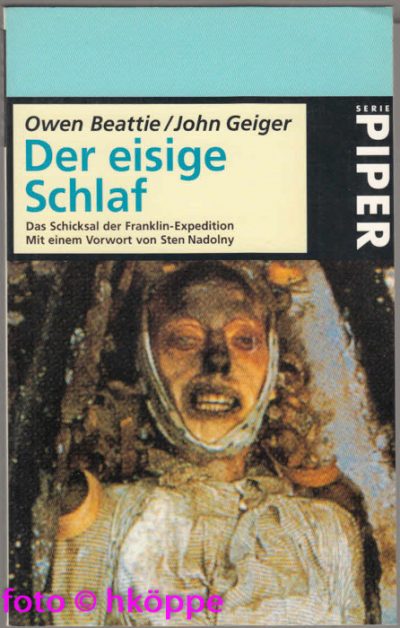

Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition

by Owen Beattie and John Geiger, with a foreword by Wade Davis and an introduction by Margaret Atwood

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2017.

$24.95 / 9781771641739

(First published by Western Producer Prairie Books, 1988; subsequent editions by Douglas & McIntyre, 1998, and Greystone, 2004 and 2014).

Reviewed by Walter O. Volovsek

We now know the fate of the Franklin Expedition of 1845-48, recorded in an updated Frozen in Time.

The Erebus was found in 2014 just off O’Reilly Island, a hundred kilometres due west of Starvation Cove; two years later the Terror was located in the shallow waters of Terror Bay.

*

We are pleased to present a review by Walter Volovsek of Greystone’s latest edition of Owen Beattie and John Geiger’s classic account of the archaeology and forensic anthropology of the Franklin Expedition, Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition.

Historical connections exist between British Columbia and Sir John Franklin’s doomed Arctic expedition of 1845-48.

Men from Franklin’s previous expeditions to the arctic, and also from expeditions sent in search of him, visited the Royal Navy’s Pacific base at Esquimalt, first used in 1848. Some of these men went on to settle in British Columbia.

Franklin’s widow, Lady Jane Franklin, who visited B.C. in 1861 and 1870,[1] is commemorated in Lady Franklin Rock in the Fraser River just above Yale.

Lead author Beattie, born in Victoria in 1949, received his Ph.D. from Simon Fraser University and taught at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alberta from 1980 until 2011. He has now retired to Victoria. –Ed

*

The revised edition of Owen Beattie and John Geiger’s Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition is a considerable improvement and an expansion of the original, published twenty years ago, which triggered my own fascination with northern exploration.

It has been reorganized into two logical sections, both with evocative chapter headings, that deal with the history of the expedition and the scientific analysis of the remains.

It has been reorganized into two logical sections, both with evocative chapter headings, that deal with the history of the expedition and the scientific analysis of the remains.

This edition is given a creative polish by a fascinating and witty introduction from Margaret Atwood, in which she presents the different incarnations of Sir John Franklin with the passage of time.

A new colour insert focuses on the recent discovery of both ships. The Erebus was found in 2014 just off O’Reilly Island, a hundred kilometres due west of Starvation Cove, where the last survivors stretched out their misery.

Two years later the Terror was located, fittingly enough, in the shallow waters of Terror Bay, where Inuit had noted its protruding mast top. Hopefully, the party that abandoned the Terror in 1848 did not strip the ships of all form of recorded evidence, much of which ended up as abandoned litter alongside more durable goods and skeletal remains.

In his foreword to this new edition, Wade Davis recapitulates the history of Arctic exploration and inserts Franklin’s contribution into it, of which the disaster that befell the expedition seems to be its greatest component. Much was gained in Arctic knowledge in the subsequent searches, launched at the instigation of Lady Franklin.

From the perspective of her endeavours to immortalize her husband, Davis unjustly devalues the contributions of Leopold M’Clintock as just “more disturbing news.”

But it was M’Clintock’s team, after all, that discovered and mapped the first remnants of the sad trek southward, and located the expedition records left by Captain James Fitzjames. More on that later.

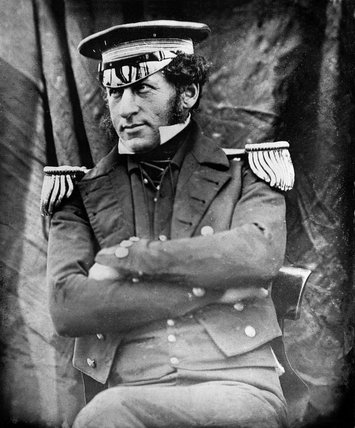

Graham Gore (later Commander of HMS Erebus), 1845. Photo by Richard Beard. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

The first section presents a comprehensive account of earlier explorations, what little we know of Franklin’s activities during his attempted conquest of the Northwest Passage, and the subsequent searches and discoveries that filled in the picture of an epic tragedy. Beattie and Geiger probe the journals of these participants for documentation of a consistent problem, described as “debility,” brought on by scurvy, as well as something else, which is only hinted at in the journals.

That tinned food was not effective in preventing scurvy, and citrus juice only helped to a degree, eventually became apparent. Fresh meat and plants were essential for avoiding scurvy. Beattie and Geiger’s key finding, however, was that the lead content of the preserved meats, soups, and vegetables was a major contributor to the mysterious fatal illnesses.

The 1845/46 over-wintering period at Beechey Island would have been uneventful were it not for the troubling deaths of three young sailors. The ships arrived in Lancaster Sound in late August.

And here I must intrude my own conjectures. The commonly accepted scenario for Franklin’s thrust further northward in 1845 strikes me as unlikely, as an early freeze-up of Lancaster Sound would have made the venture risky. William Battersby, author of a recent biography of James Fitzjames, speculated that perhaps Franklin was in search of the Open Polar Sea.[2] At the same time Battersby confessed to me in an email his doubts that the northward venture was accomplished in 1845.

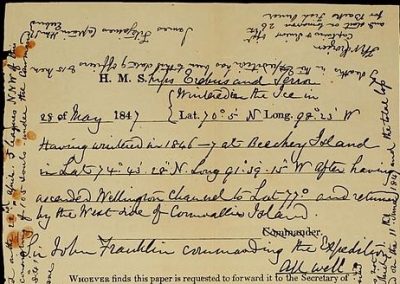

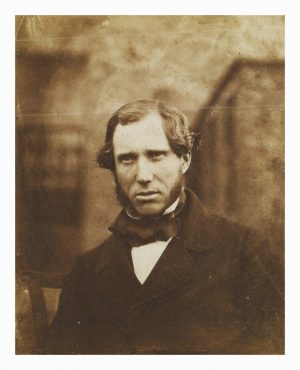

As Captain Fitzjames was a key player in the Franklin tragedy, I will take the liberty to focus on him, especially as he was the author of the expedition’s only surviving documents. The records he left appear puzzling in certain respects, and we can attribute those slips to the effects of lead poisoning; closer scrutiny, however, suggests other explanations.

I devoted much time to studying scans of the two surviving records and their interpretation by historian of medicine Richard Cyriax in 1958.[3] Both reports were prepared on standard Admiralty forms by Fitzjames aboard the Erebus in some haste, as a reconnaissance party was about to leave for King William Land – not known to be an island at the time – under the leadership of Lt. Graham Gore. The entries on them are not identical, but the one obvious error for the Beechey Island over-wintering date is repeated in both. One of them was to be placed in the cairn left at Victory Point by arctic explorer Sir James Ross in 1830.

I was struck by the peculiarity of Fitzjames’ letter a: his capital is simply a small case letter written larger, as in his entries for All well, or April. If we accept that, we have to change the meaning of the passage referring to the trip around Cornwallis Island. The sentence following the coordinates for Beechey Island should read: After [as in Afterwards] ascending Wellington Channel to Lat 770 and returning [this is the phrasing used in the Gore Point document, which I think is clearer] by the West side of Cornwallis Island. Fitzjames chooses his verb structure to separate the periods: Wintered in the ice . . . [most recent]; Having wintered in 1846-7 . . . [the earliest, with its incorrect date]; After ascending and returning . . . [between the two].

I was struck by the peculiarity of Fitzjames’ letter a: his capital is simply a small case letter written larger, as in his entries for All well, or April. If we accept that, we have to change the meaning of the passage referring to the trip around Cornwallis Island. The sentence following the coordinates for Beechey Island should read: After [as in Afterwards] ascending Wellington Channel to Lat 770 and returning [this is the phrasing used in the Gore Point document, which I think is clearer] by the West side of Cornwallis Island. Fitzjames chooses his verb structure to separate the periods: Wintered in the ice . . . [most recent]; Having wintered in 1846-7 . . . [the earliest, with its incorrect date]; After ascending and returning . . . [between the two].

It makes sense for the thrust northward to have happened in 1846, when there was much more time for the venture. Their return would have lined them up for proceeding southward along Peel Sound, and their entrapment in the M’Clintock Channel ice conveyor later that year. The remaining time prior to total freeze-up in 1845 was probably spent exploring the vicinity of their winter camp and setting up the stations for the scientific investigations on Devon Island.

Iron plate cannister in which Lieut. Gore left his letter in cairn in May, 1847. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

Fitzjames — in command of the Erebus after 11 June 1847 — later added to his original record, which Gore had placed in the cairn at Victory Point. This time, he wrote his remarks at Crozier’s Landing, where the remaining survivors were preparing to start on a desperate march southward. He had sent Lt. John Irving to retrieve the record, and most likely added his sad commentary as Irving waited at his side.

The follow-up entry on the Victory Point document opens up another mystery. Why does the author elaborate so over the confusion of the cairns? I think he provides the answer with the word ‘under’ [a change from ‘in’, written in previously, according to Cyriax]. From that information we can infer the following scenario:

In late May 1847 the Gore party located the Ross cairn, but could not find the Ross record. They assumed the sealed cylinder located within the cairn [as reported by Ross] had been pilfered by the Inuit, and they decided to bury theirs underneath the cairn for safety.

The party then continued to explore the eastern side, found promising leads opening southward, and rushed back with the good news. In early June they left the second sealed record in a cairn at Gore Point, south of Collinson Inlet. Returning to the Erebus, they found Franklin on his deathbed. Fitzjames later altered his initial May entry to June, as their absence was mostly in that month. He also added the number 28 to his original entry to indicate the likely date Gore had placed the record under the Victory Point cairn.

When Lt. Irving searched for the record placed by the late Graham Gore the previous year, he had to demolish the entire cairn, and search through the frozen ground to find it. [Hobson found a broken pick axe and a discarded canister at this location in 1859]. A new cairn was constructed a bit to the south to house the altered record, placed in a new unsealed canister, in what was thought to be the proper location.

There is no doubt in my mind that a good portion of the crew abandoned the desperate march and headed back to the ships, quite likely under the leadership of Fitzjames. The orientation of the returning boat is the first hint. The best evidence, however, is supplied by the well-organized grave of Lt. Irving, which would have taken some time to prepare. The burial could not have happened during the disorganized and hasty departure in late April 1848. Irving must have been part of the returning party and died on the way back or aboard the ships.

Inuit recollections, recorded by Charles Hall, Frederick Schwatka, and others, bear out the presence of people on the ships, both living and dead, and document the ships’ relocation in a relatively short interval of time, which cannot be attributed to ice drift alone. The corpse of a “giant” in the Erebus may have been Fitzjames, who appears to have been a large man. All things considered, Fitzjames was a key player as the hopeless circumstances bore down on the remaining survivors.

So much for my own speculation. It perhaps has no place in a book engendered from the published historical record and hard science, but those very parameters are invitations for a closer scrutiny and some calculated guesswork.

The closing chapters of the first section bring us to the surveys in the 1980s by forensic anthropologist Owen Beattie along the route of the expedition’s 1848 death march and the collection of such skeletal remains and artefacts as could still be found. Analysis of bone fragments confirmed cannibalism in the desperate trekkers, first reported to a shocked Victorian audience by the indomitable Arctic explorer Dr. John Rae, at the cost of a knighthood.

In the second section of Frozen in Time, attention shifts to the scientific investigations of the Beechey Island camp, including exhumation of the three unfortunate seamen. All died young, with the first two only three days apart. A post-mortem autopsy on the body of John Hartnell suggests that worry about such unusual morbidity was already pervading the camp.

Autopsies on the well-preserved bodies 140 years later indicated that lung infections overwhelmed the unfortunate crewmembers once they became debilitated by lead intoxication. Isotope studies matched the lead found in hair samples and organs to the type of lead that was the major constituent of solder used in the construction and sealing of the tin cans, a very novel technology at the time. A further problem was indicated by improper sealing that resulted in spoilage of part of the supply, on which the expedition was so dependent.

I find the circumstances of Hartnell’s burial especially heart wrenching; he died on 4 January 1846, three days after John Torrington. His brother Thomas must have been fighting back his tears as the coffin was lowered in a snowstorm. He had given his shirt for his brother to be buried in, and presumably kept John’s as a lingering bond between them. Captain Edward Inglefield, R.N., who was only able to break into the coffin sufficiently to comment on his face and the cotton shirt he was wearing, would subject Hartnell to a second attempt at an autopsy in September 1852.

As the authors point out, the underlying cause of the disaster was a total reliance on new, untested technology and a complimentary inability to look at the time-tested methods of arctic survival by what were deemed to be inferior people. The unravelling of the Franklin mystery brings up the relevant question of what we have learned about toxin exposure through our food supply in the intervening 170 years. The answer seems to be, very little. Various formulations of plastics are the current chemical cocktail that has invaded the bloodstreams of many Canadians, and most likely affected sperm production by males in technologically advanced societies. T.S. Eliot was right. The world may end, not with a bang, but a whimper after all.

Marc-André Bernier setting a marine biology sampling quadrant on the port side hull of H.M.S. Erebus, 2014. Thierry-Boyer photo, Parks Canada.

In all its dimensions, this new edition of Frozen in Time is a mesmerizing and thought-provoking book, especially as we are on the cusp of new revelations from the shipwrecks – located with modern technology where the collective memory of the Inuit had placed them. It also seems a good fit in our current brave new world, when we are starting to come to terms with the limits of our current technological dependency and its hidden costs.

*

After studying medicine and managing the biology labs at Selkirk College for 24 years, Walter O. Volovsek retired to a second voluntary career: developing walking and ski touring trails for the Castlegar community. Most of these are also presented to the user as conduits into the past by means of interpretive signage and related essays on his website www.trailsintime.org. This led to connections with descendants of important Castlegar pioneers, and in 2012 Walter self-published his biography of Castlegar founder Edward Mahon, The Green Necklace: The Vision Quest of Edward Mahon (Otmar Publishing, 2012). Mahon was also known for his legacy of parks and greenways in North Vancouver. Walter has also written a book on his trail-building efforts, Trails in Time: Reflections (Otmar, 2012), and has been commissioned to develop signs in key locations including Castlegar Millennium Park, Castlegar Spirit Square, and Brilliant Bridge Regional Park. Walter currently writes a history column for the Castlegar News.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] Dorothy Blakey Smith, editor, Lady Franklin Visits the Pacific Northwest: Being Extracts from the Letters of Miss Sophia Cracroft, Sir John Franklin’s Niece, February to April, 1861 and April to July, 1870 (Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1974).

[2] William Battersby, James Fitzjames: The Mystery Man of the Franklin Expedition (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2010).

[3] Richard J. Cyriax, “The Two Franklin Expedition Records Found on King William Island,” The Mariner’s Mirror 44:3 (1958), pp. 179-189

Leave a Reply