A ponderosa pine time capsule

Karen Autio's kidlit book cleverly reflects upon settler impact on the Okanagan Valley and the Syilx people over the life of a Ponderosa Pine (1780 - 2003).

March 25th, 2019

Author Karen Autio (l.) with illustrator Loraine Kemp in Wild Horse Canyon.

From a seedling to its death in 2003’s Okanagan Park fire, the tree survives eras from the fur trade, gold rush days, and sternwheelers to the Kettle Valley railway construction, finally succumbing to climate change.

Growing Up in Wild Horse Canyon

by Karen Autio, illustrated by Loraine Kemp

Vancouver: Crwth Press, 2018

$25.95 / 9781775331902

Reviewed by Ken Mather

*

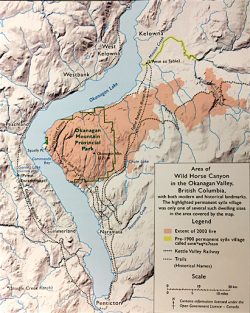

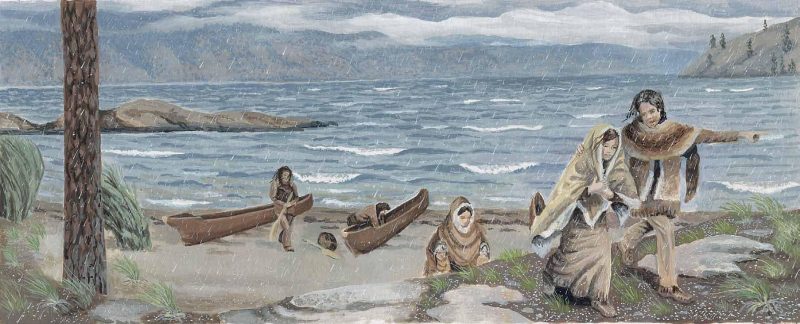

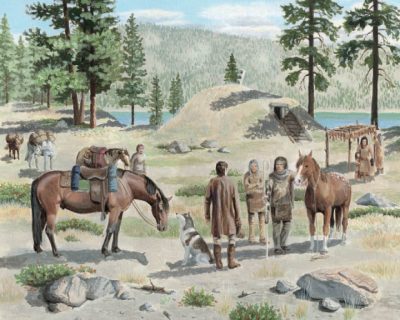

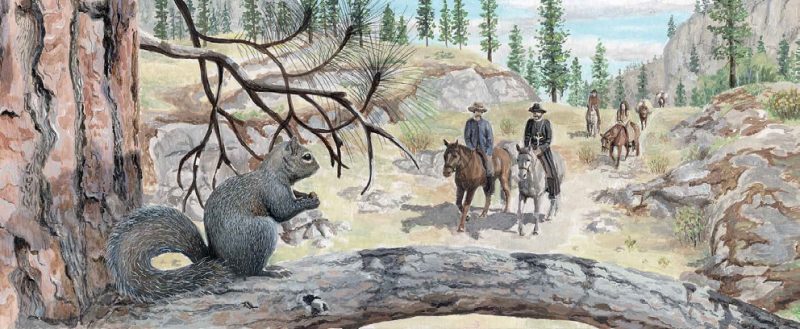

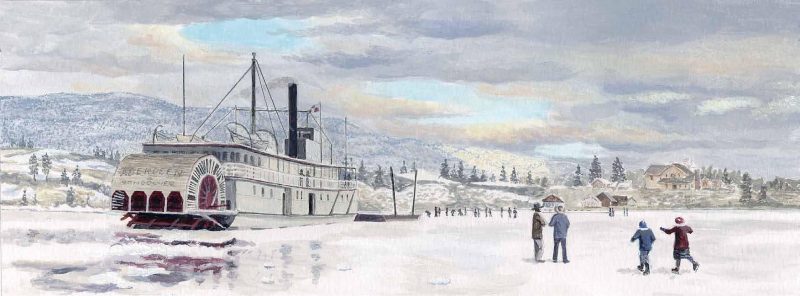

At the heart of Growing up in Wild Horse Canyon is the beautifully illustrated story of the life of a Ponderosa Pine from a seed in the year 1780 to its death in the Okanagan Park fire in 2003. As the tree grows, the story is told of the history of the Okanagan valley and the Syilx people, who have seen profound changes to their culture during the same period of time. The story uses Wild Horse Canyon, located on the east side of Okanagan Lake as the focus of its episodes, which include the arrival of the first fur traders in 1811, the fur brigades that travelled the valley in the first half of the 1800s, the B.C. gold rush era, the arrival of Father Pandosy in 1859, the arrival of settlers, the sternwheeler era, logging, the Kettle Valley railway construction, the round-up of wild horses to sell to the Russians in 1926, and the use of the Wild Horse canyon area for training Chinese commandos in 1944.

At the heart of Growing up in Wild Horse Canyon is the beautifully illustrated story of the life of a Ponderosa Pine from a seed in the year 1780 to its death in the Okanagan Park fire in 2003. As the tree grows, the story is told of the history of the Okanagan valley and the Syilx people, who have seen profound changes to their culture during the same period of time. The story uses Wild Horse Canyon, located on the east side of Okanagan Lake as the focus of its episodes, which include the arrival of the first fur traders in 1811, the fur brigades that travelled the valley in the first half of the 1800s, the B.C. gold rush era, the arrival of Father Pandosy in 1859, the arrival of settlers, the sternwheeler era, logging, the Kettle Valley railway construction, the round-up of wild horses to sell to the Russians in 1926, and the use of the Wild Horse canyon area for training Chinese commandos in 1944.

Each vignette is accurate and faithfully illustrated. Although only 25 pages long, the ongoing story provides an overview history of the Okanagan Valley with particular emphasis, respect, and sensitivity toward the Syilx people.

The story is intended for a juvenile audience, as specified in the colophon (a new word I learned that means the page on the back of the title page with the ISBN), but the book is much more than a young person’s story. It includes a glossary and pronunciation guide for Syilx words, a timeline for the Okanagan Valley, and an extensive twelve-page section on “More about Wild Horse Canyon and Area.” These added resources make the book an excellent contribution to high school studies on the Aboriginal people. As the B.C. curriculum overview on Aboriginal Studies makes clear:

Many years ago, classroom resources had few references to Aboriginal people or, if they did, it was often superficial or incorrect. As curriculum processes evolved, resources began to include some information about Aboriginal people but not how Aboriginal perspectives and understandings help us learn about the world and how they have contributed to a stronger society. Now, with the education transformation, the province is attempting to embed Aboriginal perspectives into all parts of the curriculum in a meaningful and authentic manner.[1]

Growing Up in Wild Horse Canyon will make a significant contribution to the curriculum goals as outlined above.

Despite the book’s considerable strengths and fine illustrations, I found a few historical inaccuracies that mar the otherwise well-researched presentation. For example, Autio asserts that “The fur trade … radically altered the traditional practices of the Okanagan people” (p. 35). Duane Thomson and Marianne Ignace’s excellent and balanced article in BC Studies (“They Made Themselves our Guests”: Power Relationships in the Interior Plateau Region of the Cordillera in the Fur Trade Era,” No. 146, Summer 2005) calls this statement into question. Thomson and Ignace conclude that, “Throughout the fur trade era the Salish nations maintained societies that were strong when measured by numbers of inhabitants, military capacity, effective resource tenure regimes, and functioning judicial and social systems.”

While it is important not to diminish the impact of white intruders on the Syilx people, it must be emphasized that the most devastating effects came with the arrival of gold miners and settlers in the valley, not in the time of the fur trade. Indeed, Thomson and Ignace conclude that “that the Salish nations’ control and exclusive occupation of lands, and control of laws, was largely undiminished by fur traders — until the gold rush initiated significantly changed conditions and different circumstances.”

I also question the assertion that “the gold rush era was devastating in the Okanagan Valley. It drastically altered rivers, creeks, and fish populations which wreaked havoc on the Okanagan people’s way of being” (p. 35).

Once again, this greatly exaggerates the impact of miners in the Okanagan Valley during the gold rush years. There were short-lived gold rushes to the Similkameen in 1859 and to Rock Creek in 1860, and a minor rush to Mission Creek near present-day Kelowna in 1860. But to state that these early gold mining incursions devastated rivers, creeks, and fish populations of the Okanagan Valley is not accurate.

Finally, I would question the statement that “raising cattle and hogs became the main industry in the Okanagan Valley” (p. 37). To my knowledge, few hogs were raised in the Okanagan in the years before orchards began to replace cattle ranching.

Despite these questionable interpretations of history, the book is an excellent resource for students as well as adults who are interested in Okanagan history, particularly in the recent history of the Syilx people who had lived here for thousands of years before their culture was, indeed, eventually devastated by the colonists.

*

Ken Mather retired in 2013 after 42 years in heritage site research, planning, administration, and management. Manager of the Historic O’Keefe Ranch from 1984 until 2014, Ken is now Curator Emeritus of O’Keefe Ranch and was awarded the Joe Martin Memorial award for his contribution to B.C. Cowboy Heritage in 2015. Ken has written a large number of articles and research reports on early ranching in B.C. for different magazines and websites. He is author of three recent histories of ranching and ranching cultures in the Canadian west, all published by Heritage House: Buckaroos and Mud Pups: The Early Days of Ranching in British Columbia (2006), Bronc Busters and Hay Sloops: Ranching in the West in the Early Twentieth Century (2010), Frontier Cowboys and the Great Divide: Early B.C. and Alberta Ranching (2013); Trail North: The Okanagan Trail of 1858-68 and its Origins in British Columbia and Washington. His self-published Ranch Tales (2014) is a compilation of his columns in the Vernon Morning Star. His latest book, Ranch Tales: Stories from the Frontier will be published in Spring 2019 by Heritage House.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnote:

[1] https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies

Leave a Reply