#4 Hubert Evans

April 08th, 2015

LOCATION: Roberts Creek Pier, 999 Roberts Creek Road, at the foot of Roberts Creek Road, Sunshine Coast.

Hubert Evans, the man Margaret Laurence revered as “The Elder of the Tribe,” anchored his boat, the Solheim, in the basin beside the pier where, Evans, having survived the trenches of World War One, met a man collecting mussels. He was catching mussels in order to catch shiners, in order to catch cod–so it took three leisurely days to catch a fish. The man convinced Evans to homestead in Robert Creek. Evans and his Quaker wife Ann began building their wilderness home nearby, on the waterfront, in 1926, taking residence in 1927. She died in 1960; he stayed for another 25 years. The property at 2973 Lower Road was still owned by the Evans family three decades after Hubert Evans died in 1986.

ENTRY:

In 1902, when he was a nine-year old in Galt, Ontario, Hubert Reginald Evans began his career as a professional writer by composing a limerick in praise of Lipton’s tea for a contest. The now-forgotten verse earned him $1. Hubert Evans later became a professional writer in British Columbia for seven decades.

Revered by his pen pal Margaret Laurence as “the Elder of our Tribe and ”The Old Journeyman,” Hubert Evans was born in Vankleek Hill, Ontario, in 1892, and started building a waterfront cabin at Roberts Creek, B.C., in 1926.

In response to the horrors he witnessed in the trenches as a soldier in WWI, Evans wrote an autobiographical novel, The New Front Line (1927), about a soldier named Hugh Henderson who migrates from older societies to the “new front line” of idealism in the wilds of B.C.

In 1927, his first year as a fulltime writer, he earned $97 less postage.

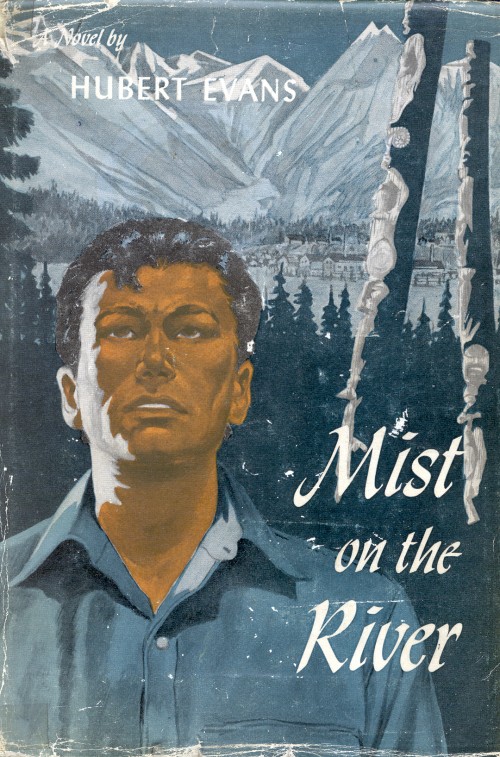

Evans is best remembered for his second novel, Mist on the River (1954), the first Canadian novel to portray aboriginals realistically as complex, central characters. This classic arose after Evans and his wife received a visit from aboriginal activist Guy Williams of Kitimaat (separate from present-day Kitimat) towards the end of WWII, requesting Ann Evans move to Kitimaat to teach his children. She had taught Williams in a residential school near the Evanses’ floathouse at Cultus Lake in the early 1920s.

Williams told the Evanses that some aboriginal children in Kitimaat hadn’t had a teacher for five years and they had forgotten how to speak English. “I had quite a number of chums in the army who were Indians,” Evans later recalled, “but it was really my wife’s Quaker concern over Indians that took us north in the first place.”

Upon their arrival in Kitimaat in January of 1945, the Evanses were greeted by the entire village. They stayed for two and a half years. “We were the only white people around,” Evans recalled. “It was 140 miles to a hospital at Bella Bella, in a gas boat mostly. Sometimes in bad weather you couldn’t get there. The Indian agent handed me the little black bag that the nurse who’d been there years before had had. He said, ‘You’re the dispenser.’ And so I coped.”

The Evanses’ experiences resulted in a short story “Let My People Go” that appeared in Maclean’s in 1947. It concerns a Gitksan schoolteacher named Cy who struggles to assimilate his stubbornly backward father-in-law, Old Paul. This led to a second Maclean’s story about the same characters, “Young Cedars Must Have Roots” in 1948.

Both stories were excerpted and serialized in the Native Voice newspaper. By the late 1940s the Evanses had moved to a less isolated mission school near Hazelton so their son could attend a one-room school.

Both stories were excerpted and serialized in the Native Voice newspaper. By the late 1940s the Evanses had moved to a less isolated mission school near Hazelton so their son could attend a one-room school.

Mist on the River follows the struggles of Cy Pitt, an 18-year-old Gitksan, destined to be chief, who leaves his village to work in a Prince Rupert fish cannery.

Dot, a relative who has turned to prostitution, warns him, “If staying a stick Indian suits you, fine. But be sure you stay one. Don’t try playing it both ways.” Throughout the novel Cy Pitt must find an original and honourable path between conflicting white and aboriginal cultures. He loves Old Paul’s orphaned granddaughter Miriam, and eventually he returns to his village where Old Paul invites him to carve one more canoe.

Meanwhile Dot’s halfbreed son Steve contracts spinal tuberculosis. The boy dies after Cy reluctantly respects the village’s superstitious fears of sending the boy to Prince Rupert for medical treatment. This incident was derived from Evans’ memory of reading the burial service over the body of a young aboriginal boy who might have survived if hospitalization had been attempted. Cy and Miriam marry, “Indian fashion,” and live together in Old Paul’s house, but Cy must return to Prince Rupert to find work.

The novel culminates in a violent confrontation between Cy and a trio of drunken aboriginals, but there is never any overt confrontation between Cy Pitt and Old Paul. The white characters in the story are peripheral throughout.

Evans later said he was absolutely determined not to falsify anything for dramatic effect: “I could have written about the injustices Indians faced. You know, like The Ecstasy of Rita Joe. I’ve seen all that. I know all that. But I had commercial-fished and trapped and built canoes with these people. I could roll a cigarette and sit on my heels and talk with them. I was one of them. I wanted to show how they were really just like us.

“This is what I wanted to do with Mist on the River. Just show them as people. Basically I was just being a reporter. . . . I knew the people. I felt for them. I was there. Not like an Indian agent or somebody like that. I was one of the guys. They cried on my shoulder. I straightened out the family problems. The rows and the boozing and that sort of thing. People say to me, ‘Do you like Indians?’ Well, I like some Indians and there are some Indians I don’t like. The same with white people.”

While nearly blind in his late eighties, hardly able to type, Hubert Evans wrote O Time in Your Flight (1979), a memoir novel of growing up in Ontario in the year 1900.

The Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize was first presented in 1985. The “Old Journeyman” died the following year.

FULL ENTRY:

Hubert Evans was a professional writer in British Columbia for seven decades. Revered by his pen pal Margaret Laurence as ‘the Elder of our Tribe’, Evans wrote Mist on the River (1954), the first Canadian novel to realistically portray Aboriginals as complex, central characters. This classic novel arose after Hubert Evans and his wife Ann received a visit from Aboriginal activist Guy Williams of Kitimaat, towards the end of World War II, requesting Ann Evans to move to Kitimaat to teach his children. Ann Evans had taught Guy Williams in a residential school near the Evans’ floathouse at Cultus Lake in the early 1920s. Williams told the Evans that some Aboriginal children in Kitimaat hadn’t had a teacher for five years and they had forgotten how to speak English. “I had quite a number of chums in the army who were Indians,” Evans later recalled, “but it was really my wife’s Quaker concern over Indians that took us north in the first place.”

The Evans arrived in Kitimaat in January of 1945 and were greeted by the entire village. They stayed for two-and-a-half years. “We were the only white people around,” Evans recalled. “It was 140 miles to a hospital at Bella Bella, in a gas boat mostly. Sometimes in bad weather you couldn’t get there.The Indian agent handed me the little black bag that the nurse who’d been there years before had had. He said, ‘You’re the dispenser.’ And so I coped.” The Evanses’ experiences in Kitimaat and Kispiox resulted in a short story ‘Let My People Go’ that first appeared in Macleans in 1947. It concerns a Gitksan schoolteacher named Cy who struggles to assimilate his stubbornly backward father-in-law, Old Paul. This led to a second Macleans story about the same characters called ‘Young Cedars Must Have Roots’ in 1948. Both stories were excerpted and serialed in the Native Voice newspaper in 1948 and 1949. By the late 1940s the Evans had moved to a less isolated mission school near Hazelton so their son could attend a one-room school.

Hubert Evans’ 1954 novel Mist on the River follows the struggles of Cy Pitt, an 18-year-old Gitksan, destined to be chief, who leaves his village to work in a Prince Rupert fish cannery. Dot, a relative who has turned to prostitution, warns him, “If staying a stick Indian suits you, fine. But be sure you stay one. Don’t try playing it both ways.” Throughout the novel Cy Pitt must find an original and honourable path between conflicting white and aboriginal cultures. He loves Old Paul’s orphaned granddaughter Miriam and eventually he returns to his village where Old Paul invites him to carve one more canoe. Meanwhile Dot’s halfbreed son Steve contracts spinal tuberculosis. The boy dies after Cy reluctantly respects the village’s superstitious fears of sending the boy to Prince Rupert for medical treatment. (This incident was derived from Evans’ memory of reading the burial service over the body of a young Aboriginal boy who might have survived if hospitalization had been attempted.) Cy and Miriam marry, Indian fashion, and live together in Old Paul’s house, but Cy must return to Prince Rupert to find work. The novel culminates in a violent confrontation between Cy and a trio of drunken Aboriginals, but there is never any overt confrontation between Cy Pitt and Old Paul. The white characters in the story are peripheral throughout.

The novel was well-received by more than 20 favourable reviews. “I read Mist on the River and have been urging people to do likewise ever since,” said Grace MacInnes, daughter of CCF founder J.S. Woodsworth. UBC anthropologist Harry Hawthorne wrote, “It is not often that tenderness is aptly combined with forceful realism and it is unique when it takes place in a young native of this province.” Evans later said he was absolutely determined not to falsify anything for dramatic effect: “I could have written about the injustices Indians faced. You know, like The Ecstasy of Rita Joe. I’ve seen all that. I know all that. But I had commercial-fished and trapped and built canoes with these people. I could roll a cigarette and sit on my heels and talk with them. I was one of them. I wanted to show how they were really just like us,” Evans later said. “This is what I wanted to do with Mist on the River. Just show them as people. Basically I was just being a reporter… I knew the people. I felt for them. I was there. Not like an Indian agent or somebody like that. I was one of the guys. They cried on my shoulder. I straightened out the family problems. The rows and the boozing and that sort of thing. People say to me, ‘Do you like Indians?’ Well, I like some Indians and there are some Indians I don’t like. The same with white people.”

Hubert Reginald Evans was born in Vankleek Hill, Ontario on May 9, 1892. As a 22-year-old journalist he provided world coverage of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland, a CPR liner that collided with a Norwegian ship, the S.S. Sorstad, during a fog on the St. Lawrence on May 29, 1914, killing 900 people. He enlisted in 1915 in the Kootenay Battalion and was wounded at Ypres in 1916. Despite his partial colour-blindness, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Machine Gun Corps in early 1918. He fought in the trenches of France and was appalled at the violence he encountered. One of his friends was killed at Mons two hours before the Armistice. Discharged in 1919 in Toronto, he was offered a job as City Hall reporter for his former paper, The World, but he declined. The city was covered with dirty snow. He wanted a fresh start. He took an army transport train out to New Westminster to visit his parents. On the train he met the Chief Inspector of Fisheries who offered him a job as his personal secretary, travelling around Europe to promote salmon sales. Evans told him, “I just tore up a job like that!” Instead he asked to be posted to the most northerly fish hatchery in B.C. A week later Evans was on another train going north to Lakelse Lake, above Terrace, B.C., beginning his life anew as a British Columbian.

In 1920, in Vancouver, he married Ann Emily Winter, most recently of Verden, Manitoba, who shared his Christian disdain for ‘unworthy ends’. While working as the superintendent of a salmon hatchery at Cultus Lake near Chilliwack, B.C., Evans sold a 500-word satirical piece to the New Yorker when Dorothy Parker and Sherwood Anderson were editors. He was paid for 17 cents per word. “It was a thing about a high-pressured business executive who had retired to the country,” he said. “His hobby was keeping bees. He used the same technique on the bees as he had used to manage his sales staff. It ended with the bees stinging him to death—which must have suited Dorothy Parker just fine.” Evans partially supported his family with the sale of twelve keenly-observed anecdotes about wildlife at Cultus Lake. After they were syndicated in the U.S., Judson Press of Philadelphia asked him for a book. Evans wrote 50 of these anecdotes for young readers in six weeks. They comprise his first book, Forest Friends, published in May of 1926. While raising their family, the Evanses lived briefly in West Vancouver and North Vancouver before moving to the Sunshine Coast on a fulltime basis in 1927.

Evans started building a cabin at Roberts Creek, B.C. in 1926. He lived there as a Quaker for most of the next 60 years. In 1927, his first year as a fulltime writer, he earned $97 less postage. In response to the horrors of World War One, Evans wrote a naive, autobiographical novel, The New Front Line (1927), about a soldier named Hugh Henderson who migrates to the ‘new front line’ of idealism in the wilds of British Columbia. He had been encouraged to write an ‘authentic’ B.C. novel by his newspaper colleague Fred Jacob and it was published upon the recommendation of novelist Frederick Niven’s reader’s report (“not the sort of book to go a-begging”). Following the acceptance of the manuscript, Evans approached Garnet Sedgewick at UBC and asked to take his course in the novel. “He said, ‘Look, if you’ve had a novel published, you don’t need to take a course.’ Well, he was wrong. I could have benefited a great deal from a course,” Evans said. He joined the Canadian Authors Association that year but was soon unimpressed by their genteel approach to writing. Evans became a trade unionist during the Depression, and helped the unemployed men survive by teaching them to fish. Hubert Evans was ahead of his time during World War II when he wrote No More Islands (1943), a sympathetic portray of the effects of internment on both Japanese Canadians and the people who knew them.

After Ann Evans died in 1960, Hubert Evans remained in their home on the beach at Roberts Creek and added some books of poetry to his prodigious output of hundreds of stories, serials, novellas and articles. While nearly blind in his late Eighties, Evans wrote O Time In Your Flight (1979) his remarkable memoir/novel of growing up in Ontario in the year 1900. Later Evans completed a somewhat simplistic juvenile novel, Son of the Salmon People (1981), about Aboriginals trying to protect their land from logging. Much of his writing had been for young readers because he and his wife believed it was important to mold young minds. They felt adults could not be altered much by fiction. The Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize was first presented in 1985. The ‘Old Journeyman’ died on June 17, 1986.

BOOKS:

Adult novels

Evans, Hubert. The New Front Line (Macmillan, 1926).

Evans, Hubert. The Western Wall (novella, 1932).

Evans, Hubert. No More Islands (novella, 1943).

Evans, Hubert. Mist on the River (Copp Clark, 1954; New Canadian Library, 1973).

Evans, Hubert. O Time In Your Flight (Harbour, 1979).

Juvenile novels

Evans, Hubert. Forest Friends (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1926)

Evans, Hubert. Derry, Airedale of the Frontier (New York: Dodd Mead, 1928).

Evans, Hubert. Derry’s Partner (New York: Dodd Mead, n.d., presumably 1929).

Evans, Hubert. Derry of Totem Creek (New York: Dodd Mead, 1930).

Evans, Hubert. The Silent Call (New York: Dodd Mead, 1930).

Evans, Hubert. North to the Unknown (New York: Dodd Mead, 1949). (biography /Alexander Mackenzie)

Evans, Hubert. Mountain Dog (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1956).

Evans, Hubert. Son of the Salmon People (Harbour, 1981).

Poetry

Evans, Hubert. Bits and Pieces: Notes for Stories that Didn’t Get Written (Harbour, 1974).

Evans, Hubert. Whittlings (Harbour, 1976).

Evans, Hubert. Endings (Harbour, 1978).

Evans, Hubert. Mostly Coast People (Harbour, 1982).

About Hubert Evans

Twigg, Alan. Hubert Evans: The First Ninety-Three Years (Harbour, 1985).

Evans: Creativity is a very strange thing, you know. Sometimes it just takes over. I think I told you there’s a passage in Mist on the River that I wrote down as if it was dictated. That poem “Questionnaire” wrote itself in half an hour. I don’t think I ever changed a word. Mind you those periods don’t come very frequently.

Twigg: And there’s a feeling of well-being you get afterwards…

Evans: Oh, yes. I think this is not understood enough by creative people. There’s an added dimension that comes into it sometimes. Mind you, you can fool yourself too. You can think you’re inspired and you’re not. But when the real thing comes, it’s serious.

Twigg: And the accompanying timelessness is fascinating. It’s a bit like being a child again and being totally absorbed in learning something.

Evans: Well, you know, there’s that saying in the Gospel, “Except ye become as little children.” That has been misconstrued and misinterpreted so often. But I think there’s something relative in that to what we’re talking about.

Twigg: There is something about being able to give yourself up a hundred percent to an activity that is quite sublime.

Evans: Sublime is a good word.

Twigg: And maybe a hockey player feels that same sublimity when he’s taking a slap shot. You play the game for those moments.

Evans: Yes. And that’s really at the basis of a lot of Zen as I understand it. It’s really the basis of Christianity, too. You become part of the great whole. You yourself as an individual don’t loom very large. You become part of something greater than yourself. You see, Einstein said a human being is a part of that great whole we call the universe but, separated from it in time and space, he perceives himself through his mind and his senses and is therefore handicapped, as if in a cage. Einstein ended up by saying our job is to free ourselves from this prison. Of course, Einstein was off on cloud nine quite often but I see what he meant.

Life to me is a process of becoming. You can’t turn back, Things are constantly changing. Even in my lifetime, look at the changes. The other night I heard that two different groups of astronomers, one in England and one in the U.S., had simultaneously come up with the statement that our solar system is a mere twelve billion years old. It’s one of the younger ones. (Laughing) “What is man that thou art mindful of Him?”

Twigg: Does professionalism take away your ability to reach that unconscious, writing frame of mind? Or does experience make it easier to reach?

Evans: It’s a mystery. I don’t see how any self-imposed discipline might change it. It’s another element. I don’t know what it is. Look at Michelangelo. Gosh, he couldn’t sleep at night.

Twigg: There must be books written about a link between creative art and religious feeling.

Evans: Well, as a Quaker, I find some sentences and quotes have been quite helpful. For instance, “He that would save his life, shall lose it. But he that loses his life for something greater than himself, shall save it.” Now I can apply that to what we’re talking about. A writer says to himself, “I’m going to write this if it’s the last thing I do.” Because you’re transported. You don’t talk to people about this. They think you’re a bit odd. But it’s a thing money can’t buy.

It’s a mysterious thing but you also have to have the tools. You can’t be expected to start off from scratch. I was talking to my neighbour, Maxie, and she had me write this out for her. It’s from Pilgrim’s Progress and it’s kind of apropos considering our ages. “Come wet, come dry, I long to be gone. And however the weather be in my journey, when I come there I shall sit and rest me and dry me.” Here was a tanner, or rather a tinker, an almost illiterate man, writing great prose. I had it read to me as a kid, and I read it as a kid. “And trumpets sounding on the other side.” Where Pilgrim’s Progress ends like that, it does something to me. As Willa Cather said, there’s some words in juxtaposition that lift the thing right off the printed page. “And trumpets sounding on the other side.”

Twigg: And those special phrases that lift off the page are usually phrases that come to the writer out of the blue.

Evans: Sure they do!

Twigg: They’re the gifts you get.

Evans: In that poem of mine, “In Perpetuity”, there’s a line “and in the hanging valleys of desire.” (Laughing) “The hanging valleys of desire” does something to me. And I don’t know why.

Twigg: If you started rationalizing, you’d take that line out. You have to trust the feeling that it works.

Evans: Yes, William Blake is full of that.

Twigg: You could make the argument that good poetry is somehow the “highest” form of writing.

Evans: That’s a point. A lot of poetry that’s being written today is skillful poetry but it lacks content. You know what I mean? It’s sound and fury signifying nothing. When it’s all done, what has it done? It hasn’t got inside my skin.

Twigg: Perhaps there is a danger that you come to value the activity of writing so much that you get hooked on the solitary pleasure. Did you ever feel that?

Evans: No, I never did. I found it essential after writing that I had to do manual work. I found that a release for me. I got pretty tight sometimes. Whenever that happened my discernment sort of dulled a bit. It’s like the guy on the newspaper at eleven o’clock at night thinking he’s writing wonderful prose until the next morning he sees what the editor did to improve it. The evidence of a professional is that you have to be enthusiastic yet you have to be a good critic. When you’re a professional you can walk that tightrope.

Twigg: It has to be an adventure that is under control.

Evans: That’s what I mean, yes.

Twigg: For some writers it’s pure adventure without control. It’s like a drug. They overdose on writing and lead self-destructive lives.

Evans: I think so. One or two of the Russians were like that.

Twigg: Kerouac, too, And Sylvia Plath

Evans: But for me, way down deep, I look upon myself as a reporter. I’m reporting life as I saw it and felt it. So I’m something apart from the writing, too. I’m sure I’ve told you this before. I’m just seeing what’s being acted on that stage. I’m merely reporting. I’m not an actor.

Twigg: Whereas the subjective writer is dreaming awake. Have you ever bothered to write down any dreams?

Evans: No.

Twigg: Many writers gain inspiration from that world.

Evans: I haven’t. Just the occasional image. When I’m tired, like I am now, I can shut my eyes and see faces. They just flood in. A montage of things. Of course I do a half hour’s meditation every morning and a half hour’s meditation every evening. I’ve been doing that for the last several months. Sometimes, not always, I can almost attain serenity for a short while. I can be quite outside “this guy.” I wish I’d done it earlier in life.

Twigg: What sort of meditation?

Evans; Well, pretty abstract. Basically Christian. A little bit of Zen, I guess. Or one of the Hindu cults. It’s what Einstein said. Get beyond the mind and the senses. To imagine myself as part of one great and inconceivably infinite whole.

There are some nights and morning when I’m just too full of myself and my worries. It doesn’t work. When you’ve got to be like I am, where you can’t even split your own kindling, I’m apprehensive. Very often this apprehension is an emotional reaction to your own helplessness, I guess. You’ve got to stop and realize that this is the process of life.

In that poem “Thoughts While Thinning Carrots” I tried to express this. I look upon nature and see cause and effect, always. I read years ago where an ecologist said that when a snowflake falls into the ocean, or a leaf to the ground, there is set in motion a chain of cause and effect that goes on forever. We don’t realize that in our social life. We rub off on one another. I will never be the same as I was before we had this talk.

This is where the writer is so vitally important. People say what does it matter? It matters. What the pharaohs did, or what primitive man did, is affecting my life. Our inter-relatedness is endless.

Twigg: And once you are aware of this, you become more appreciative and careful about your dealings with everything.

Evans: Sure. “That of God in every man” is what the Quakers have said for centuries. I mean, I try not to be derogatory or heedless or mean to anybody. Because we are made of one another. This inter-relatedness in life. I wish you’d write a novel about that. Think that one over for a few years. We impinge, impinge, impinge on one another.

Twigg: Robertson Davies’ Fifth Business starts when a boy throws a snowball, misses his target and hits a pregnant woman who gives birth prematurely. A chain of events is set forth for three novels from that one incident.

Evans: That should be emphasized in fiction particularly. And in movies. And in plays. I’m convinced of that. I can’t see that man is any exception from nature. That is why I tend to think that life isn’t a one-time thing. A Buddhist, I think, believes that anything that is learned in this lifetime isn’t lost. If you’re going to be stupid enough not to learn any lessons, you’re going to stay in a backward class for millennia. My brother called me from Minneapolis the other night, where he’s an invalid now. He’s way out, a Ph.D. about four times, a physicist and a biologist. He said, “All I’m looking forward to is oblivion.” I said, “Aren’t you lucky?”

Twigg: But he was serious.

Evans: Oh, yes. But I don’t think in the end we get away with anything.

Twigg: Getting back to that chain of enlightenment idea… it does seem to be true that if you have a negative altercation with somebody, it somehow rubs back on you.

Evans: It does indeed. Because the other person is a part of me. An old Buddhist told me once that it is conceivable that there are eight dimensions. I don’t’ know about that. But I can remember when the fourth dimension was considered a pretty screwball idea. How do you know there isn’t a dimension after dimension after dimension? When I can hear that our solar system is a mere twelve billion years old, whew! “When I behold the heavens, the work of Thy hands, what is Man that thou art mindful of him?”

Twigg: I think we’re talking about maintaining a reverential approach to life.

Evans: Most people, when you use that word reverential, think you’re talking about churches. Or some static form of religion.

Twigg: But in fact reverence is an essence of religion.

Evans: Sure. It isn’t pantheistic.

Twigg: So one can be religious simply by communing with nature in a reverential way.

Evans: Sure. I mean, the Iroquois and the Sioux, they worshipped the elements. The Indians do that up on the north coast. The old man worshipped the sea. They sat in awe.

Twigg: Maybe the writer, because he can slow down and repeat moments for people, is important because he can show us the importance of looking, of really seeing. Of appreciating life more deeply.

Evans: Sure. I remember my father telling me a story. He’d probably heard it from someone else. A carpenter was making a table. He was busy planing the underside of the boards. Somebody came along and said, “What do you want to be fussy about that for? Nobody will see that.” And the old guy replies, “God will see.” (Chuckling) You can transpose that into writing. Or into any activity.

[Interview conducted at Roberts Creek, 1984]

HUBERT EVANS was born in Vankleek Hill, Ontario in 1892 and raised in Galt, Ontario. He worked as a reporter before enlisting in 1915. He married in 1920 and built his permanent seaside home at Roberts Creek, BC. His first novel, The New Front Line (1927) is about a pioneering World War One veteran in BC. He and his wife also lived in northern BC Indian villages, resulting in his acclaimed second novel, Mist on the River (1954). His 0 Time in YourF1ight (1979), written in his late eighties despite near blindness, recounts a year in the life of an Ontario boy in 1899. Revered by Margaret Laurence as “The Elder of our Tribe,” the Quaker outdoorsman also published two hundred short stories, sixty serials, twelve plays, three juvenile novels, three books of poetry and one biography. Hubert Evans died in 1986, after seven decades of professional writing. He was interviewed in 1982 and 1983.

T: Tell me about how you came to write 0 Time in Your Flight.

EVANS: The second time I went to the hospital to get my heart pacer batteries renewed, they opened me up and found something else was wrong. I was in bed for weeks. I thought by golly, time’s a-wastin’, I better get some of the family history down. So my son-in-law brought me one of those Dictaphones from his office. I was awake a lot at nights so I just started in stream-of-consciousness. I could taste the food and smell the smells. Some nights I’d talk two chapters.

Those days I could still see to do a little hunt n ‘peck typing so in the daytime I typed it out pretty well just as I said everything. It ran to sixty-five thousand words. I had a copy made for the children and then I sent a copy to the Ontario Public Archives. But in

the back of my oId free lancer’s mind, I must have figured I might be able to use this. I told them I wanted it kept under wraps until 1980.

Then four or five years ago I couldn’t go out and saw wood or go fishing any more on account of my heart. I was sort of at loose ends so I did ninety pages of the book. But the viewpoint I had wasn’t any good. It was too subjective and modern.

You see, I’m an oldtimer. After sixty years I still see a story as a play. The characters are on an imaginary stage and I’m a member of the audience. I just try to get them to show themselves. This can be very limiting. On the other hand, I think it narrows down the focus.

T: So you needed a more objective approach to get you going.

EVANS: Right. So I decided to see the whole world through the yes of a nine-year-old that was me. Anything the boy couldn’t comprehend at the time, I just left out. I tried to do as little interpreting as possible. It was like the title. I don’t explain where

that phrase 0 Time in Your Flight comes from because I never knew it was from a poem when I was a boy. it was just something my mother said. This has been one of the main tenets of my writing all along: It’s far better to have a reader miss a point than hit him over the head with it. If you get the reader concluding, “I know what that character is up to,” then you’ve got participation. The reader becomes part of the story when he’s seeing around corners.

T: I imagine writing novels for young people would have helped you learn that approach pretty quickly.

EVANS: Yes, it’s been very helpful. I’ve often though that.

T: And it would also force you to simplify your language.

EVANS: Exactly. Now if I was running one of those creative writing courses in a university, I would have an exercise where people tell stories in Basic English. English has taken on far too many words. There are too many tools.

I know an old chap who retired near here who used to be a big time businessman. One day he decided he was going to take up carpentry. So he goes out and buys several hundred dollars worth of electric tools. But this is a guy who can’t even sharpen a hand saw or a chisel! Both my grandfather and father were excellent carpenters even though they had very few tools. They knew how to sharpen them! By golly, they knew how to use them and when not to use them.

It’s the same with language. We’ve got all these words, all these tools. Think of one of the Lake poets writing on the death of a child, then think of Issa, the Japanese poet in the 1500s. Issa on the death of his child uses only twelve words. Whenever I recite it, it still moves me:

Dew evaporates

All our world is dew

So dear, so fleeting

T: Reviews as far back as the 1920s mention your “spare, lean and vigorous style.” Did you have to learn to write that way?

EVANS: I’m a two-time high school dropout. The second time I left school I went to work for a newspaper called the Galt Reporter. My boss there had been the editor of a prestigious paper called the Chicago Inter-Ocean. When I arrived he said two things to me. Learn to use a typewriter within two weeks or you’re out. And as far as possible, use words that the boy who sells your paper can understand. Then you’ll be writing good English. That’s always stuck.

T: Would you say your approach to writing is very much like your approach to life?

EVANS: Yes, I suppose that’s true. I knew my wife ever since we were thirteen and we both always had the same idea. To travel light. To not have any encumbrances. To own only what you can carry on your back. For instance, we said we would never own land. Then her home broke up back east and we got sent this piano. Then we had kids. We had to have a roof over our heads so I built this house.

T: How did you become a Quaker?

EVANS: It’s a long, long story. My wife was a graduate of the University of Toronto. One of the books she got me reading was Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus. That book really became my Bible. “Always the black spot in our sunshine. This is the shadow of ourselves.”

You see, I went through two years and three months in the trenches in World War One. I tell you, I got pretty damned cynical. I had got to a stage where I would say how the hell does anybody know what beauty is? I remember saying this to myself. I remember thinking a tree may be as ugly as the hair on my arm.

In Sartor Resartus his protagonist reaches this point and says he’s not going to put up with it. He decides the world is not a “charnel house filled with spectres.” From that day on, his attitude changes. Well, in those days there was a thing in Philadelphia called the Wider Quaker Fellowship. My wife and I asked to join because we were universalists.

The Quakers have no creed. They have no minister. It’s an attitude. If you believe in life and growth, you can be a Quaker.

T: Did you always want to be a writer?

EVANS: I always thought about it. After I came out of the army I went up north for a year and started writing. In those days, if you could put a short story together, you could sell it. But you couldn’t make a living just by writing for Canada. So I wrote pulp stories. The most popular kind back then were war stories by American guys who’d never even been there. I couldn’t write about violence so I wrote outdoor stories. Animal stories.

T: What made you start writing for kids?

EVANS: My wife said she’d rather have me digging ditches than writing pulp. Mind you, I’ve never written anything that I’m ashamed of, but I’ve written a lot of things that really didn’t need to be written. She suggested I write for teenagers because you can still change a person’s viewpoint up to the time they’re twenty.

T: How old were you then?

EVANS: I was thirty or so. The first thing I did was a syndicated column about factual things I’d seen with animals. The Judson Press in Philadelphia wrote me and asked me to do a book about it. I wrote about sixty-five of these columns in six weeks. The book sold quite well.

T: Was making a living as a writer in the 1920s easier than today?

EVANS: Much easier. If you could tell a story, the market was there. Today I don’t know how people can make a living with fiction. TV has changed everything so much.

T: Did you get much notoriety in those days?

EVANS: Well, listen. When I was doing those outdoor nature stories, I was living in a very fine house in North Vancouver. This was the late twenties. A piece ran in every daily paper across Canada saying Hubert Evans lives in a one-room shack far away from civilization! The truth was I’d never had it so good! I was really in the money.

T: But you’ve lived through long periods of being virtually unknown.

EVANS: Yes, yes, yes! Of course these days if a writer wants to make headlines he practically has to perform some unnatural act with a farm animal.

T: Perhaps if you hadn’t separated yourself geographically…

EVANS: No, I’d had it up to here with cities. This is what I wanted. I wrote to various postmasters along the coast looking for a sheltered cove, a sandy beach, good anchorage and a creek. I came to Roberts Creek and bought this half-acre of waterfrontage for a thousand dollars cash.

T: If you hadn’t always written for money, do you think you would have produced more than three adult novels?

EVANS: Maybe I would have. But I haven’t got that intense perception and psychological imagination that say a Margaret Laurence or a Graham Greene has.

T: What made you write your novel about the Indians of northern BC, Mist on the River?

EVANS: Well, I had quite a number of chums in the army who were Indians. But it was really my wife’s Quaker concern over Indians that took us north in the first place. She had this book by an American called Indians are People Too. This is what I wanted to do with Mist on the River. Just show them as people. Basically I was just being a reporter.

I could have written about the injustices Indians faced. You know, like The Ecstasy of Rita Joe. I’ve seen all that. I know all that. But I had commercial-fished and trapped and built dugout canoes with these people. I could roll a cigarette and sit on my heels and talk with them. I was one of them. I wanted to show how they were really just like us.

T: Donald Cameron has described that book as “a good man’s compassionate regard for another’s pain.”

EVANS: Bertrand Russell said, “If we want a better world, the remedy is so simple that I hesitate to state it for fear of the derisive smiles of the wise cynics. The remedy is Christian love or compassion.” D.H. Lawrence kept on this, too. What the world needs is compassion.

One of my problems as a writer is that I’ve never been able to write about middle-class, Kerrisdale- West Vancouver people. My head tells me they’ve got their tragedies and disappointments and dramas like everyone else, but this is one of my blind spots. I’m sorry to say I can’t get inside their heads the way I do with older people or down-and-out people or children.

T: Maybe it’s because those people will never allow you any communal feelings with them.

EVANS: It’s true, I think we do all need to feel ourselves part of a larger family. Living with the Indians for eight years in the Skeena country taught that to my wife and me. The Indians have still got this. But most of us have really lost it.

Of course there are lots of Indians I don’t take to, just like there are lots of white people I don’t take to. But there’s a quotation by Albert how do you pronounce it? Is it Camus? Is that the right way? He said there is no question here of sentimentality. He said, “It is true that I am different by tradition from an African or a Mohammedan. But it is also true that if I degrade them or despise them, I demean myself.”

T: That hearkens back to that Camus quote above your writing desk.

EVANS: I can repeat that one by heart. “An artist may make a success or failure of his work. He may make a success or failure of his life. But if he can tell himself that finally, as a result of his long effort, he has eased or decreased the various forms of bondage weighing upon Man, then in a sense, he is justified and can forgive himself.”

[STRONG VOICES by Alan Twigg (Harbour 1988)] “Interview”

[INFORMATION POSTED JANUARY 1, 2016]

Leave a Reply