#291 Disturbing: The Peace

April 21st, 2018

Breaching the Peace: The Site C Dam and a Valley’s Stand against Big Hydro

by Sarah Cox, foreword by Alex Neve

Vancouver: UBC Press (On Point Press), 2018

$24.95 / 9780774890267

Review by John Gellard

*

From UBC Press’s new On Point Press, which aims to “introduce a broad audience of readers to current thinking and new ideas about history, politics, Indigenous studies, the environment, and the natural world,” comes Breaching the Peace, by journalist Sarah Cox.

From UBC Press’s new On Point Press, which aims to “introduce a broad audience of readers to current thinking and new ideas about history, politics, Indigenous studies, the environment, and the natural world,” comes Breaching the Peace, by journalist Sarah Cox.

BC Hydro — not content with building the W.A.C. Bennett dam on the Peace River in 1968, which flooded the upper Peace, Finlay, and Parsnip rivers to create a reservoir with a total area of 1761 square kms and inundate the traditional territories of the Tsay keh Dene (Ingenika) and Kwadacha (Fort Ware) people; or with building the Peace Canyon Dam in 1980, which created 21-km Dinosaur Lake out of a major palaeontology site – announced in 2010 the construction of a third dam on the Peace River, at Site C west of Fort St. John. The dam would flood more than 125 sq. km of Class 1 to 7 agricultural land, along with 100 sq. km of forested land. The project would require the largest withdrawal from the Agricultural Land Reserve in B.C.’s history.

Site C has been controversial ever since that 2010 announcement.

Among the first acts of BC’s new NDP government was the approval of BC Hydro’s Site C project on December 11, 2017. Premier John Horgan had previously allied himself with the resistance to Site C and had even contributed $100 to the “Stakes in the Peace” campaign, which created a field of yellow stakes in the Boon Family farm at Bear Flat on the Peace west of Fort St. John.

Treaty 8 Tribal Association members West Moberly First Nations and Prophet River First Nation have launched a civil action claiming that Site C and the two previous dams on the Peace unjustifiably infringes on their constitutional rights under Treaty 8.

A third Treaty 8 Nation that is not a member of the Tribal Association, Blueberry River First Nations, has also launched a law suit claiming that the cumulative impacts of industrial development, including Site C, are a violation of Treaty 8. Both cases will be heard starting in July.

Here reviewer John Gellard assesses the many angles of BC Hydro’s latest adventure in power politics, legal and corporate intimidation, and large-scale and irrevocable environmental destruction – Ed.

*

Breaching the Peace is an excellent title for Sarah Cox’s important book about the Site C Dam.

That title yields a cascade of kaleidoscopic connotations — insights into this complex history of a river being broken up, of communities being divided, of “breach of the peace” lawsuits, and of byzantine machinations by BC Hydro to overcome the resistance.

Well, where is the Peace River, and what is the Site C Dam?

The headwaters of the Peace rise in the Rocky Mountain Trench in northern British Columbia, 58 degrees north latitude, a couple of hundred miles north of Hudson’s Hope. Trending south, the river is fed by tributaries such as the Finlay from the north and the Parsnip from the south, draining a watershed the size of Ireland.

The headwaters of the Peace rise in the Rocky Mountain Trench in northern British Columbia, 58 degrees north latitude, a couple of hundred miles north of Hudson’s Hope. Trending south, the river is fed by tributaries such as the Finlay from the north and the Parsnip from the south, draining a watershed the size of Ireland.

Then, 50 km west of Hudson’s Hope, the river finds a gap in the Rocky Mountains and turns east through the Peace Canyon, a migration route as old as the dinosaurs. At Hudson’s Hope the canyon opens up into a wide alluvial valley stretching 83 km to Fort St John, after which the river flows on into Alberta, ending at the Athabasca Delta.

At Fort St. John, the 1100 megawatt Site C Dam is being built. The price is the flooding of thousands of hectares of rich bottomland, creating a reservoir stretching back to Hudson’s Hope.

The Site C Dam is what all the fuss is about, but it must be seen against a background of previous “breaches” of the Peace, places where the river has been converted from a life- supporting ecosystem into a machine to generate electricity.

Going up Peace River rapids before Bennett Dam was built; area is now deep beneath Williston Lake. Hudsons Hope Museum image.

The first “breach,” near Hudson’s Hope, is the 3000 megawatt W.A.C. Bennett Dam. A sterile reservoir has replaced a living river system.

“By all accounts the lattice of rivers, canyons, estuaries and forests … had been of a wild, dizzying beauty,” Cox writes. “Rivers like the Finlay and the Parsnip were used by the First Nations as highways. When the Bennett Dam opened up [in 1968]… some people had to flee so quickly that they lost [everything]” (p. 99).

“Oh it was beautiful,” says Elizabeth, mother of Roland Willson, West Moberly chief. “A nice big wide valley. Big beautiful timber, just sand bars and cut banks…You could run for miles. Lots of animals … big baldheaded eagles sitting out there. Now there’s nothing.”

Yes, the purpose of the Bennett Dam is to generate electricity, but does Williston Lake not provide some benefits? Fishing? Afraid not. The bull trout, full of methyl mercury from rotting vegetation, are unfit to eat. The caribou are almost extirpated. The West Moberly and the Saulteau have a captive breeding program. The moose are disappearing because of flooding and fracking.

“Twenty years ago moose were all over the place,” says Marvin Yahey of the Blueberry River First Nation. “Nowadays, you have to go to the extreme to find one…. When you just open up those animals, there’s huge cysts and lumps on the kidneys…the meat is all yellow and tarnished and smells like natural gas. How do you eat that?”

The Tsay Keh Dene who live at the north end of the “lake” (Williston Reservoir) still do not have hydro power.

The land replaced by the Williston Reservoir is fading from memory. It’s not much good for recreation because the “lake” is full of debris and the banks are still sloughing. We should not forget it entirely.

Twenty km downstream from the Bennett Dam is the Peace Canyon Dam, generating 700 megawatts. Its reservoir is called Dinosaur Lake. The dinosaur remains are fifty metres under water.

Then the valley widens into a “Garden of Eden” ecosystem. The river meanders slowly between banks of rich alluvial Class 1 topsoil two metres deep. Farms on the north bank facing the sun in the long summer days produce fruit and vegetables to rival Fraser Valley produce.

Productive Peace River farmland threatened by inundation by the Site C reservoir. Robin Bodnaruk photo.

On the gentle slopes, Class 2-5 soils yield hay and alfalfa. It’s 83 km to Fort St John where the 60-metre Site C Dam will rise to drown 100 km of valley if you include the Moberly and Halfway Rivers.

Agronomist Wendy Holm says that this section of the Peace valley could grow enough fruit and vegetables to feed a million people. So why is the farmland not being developed to its full potential? Farmers living in the shadow of having their property flooded have hesitated to clear their land and develop it for agriculture.

One farm that is well developed belongs to Ken and Arlene Boon. Arlene’s grandfather built their house. Highway 29 from Fort St. John curves downhill around the farm and separates the alluvial bottomland, called Bear Flat, from the slope where the Boons grow hay and graze cattle.

The highway here beside the river is being rerouted by Hydro so that it will pass through the farmhouse site. There is constant noise from drilling by “The landlord from Hell.”

Resisters are carrying on a “yellow stakes” (Stake in the Peace) fundraising campaign described in the book.

Yellow stakes campaign: Ken and Arlene Boon with grandson at their home on Bear Flat. Matt Preprost photo, Alaska Highway News.

Cox describes other convoluted dealings between the Boons and BC Hydro: expropriation and an eviction notice for Christmas, 2016, then a reprieve and a deal whereby the Boons can lease back part of the land. There was a proposal by farmers to bargain collectively in land sales. Hydro’s rejection of that idea is seen as a “divide and conquer” tactic.

The farms have a symbiotic relationship with the wild land. The forests are important hunting grounds, especially for Indigenous people. Forested islands allow ungulates to breed and migrate out of reach of predators. The fish are still fit to eat.

Just upstream from the Boons’ place is Watson Slough, a 20-hectare wetland called “one of the worlds birding hotspots.” It supports 130 nesting bird species including trumpeter swans as well as rare “outlier” plant species. Hydro was beginning to clear-cut the trees, but was persuaded to leave Watson Slough alone for a while.

A tufa seep is a “magical” phenomenon whereby mineral laden water seeps slowly over long distances and emerges to create unique mineral formations that support rare plants and animals. There are about seven tufa seeps that will be lost.

Rocky Mountain Fort is on the south bank, by the Moberly River, just upstream from the dam site. The Pedersens’ farm high on the north bank has an excellent view of it. You can also see the machines working on the dam and get a glimpse of the landslides — “tension cracks” — that could well drive the cost over the current $12 billion. In 1793, Alexander Mackenzie noted an abundance of bison and wildlife here. Hydro has clearcut the area for a rock debris dump.

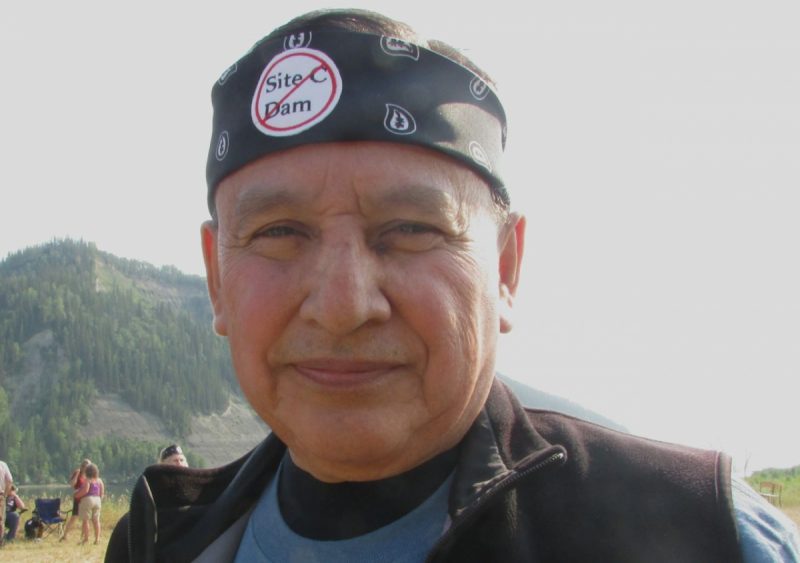

L-R: Helen Knott, David Suzuki, Ken Boon, Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, at the Treaty 8 camp, Rocky Mountain Fort, February, 2016. Sage Birley photo.

On New Year’s Eve, 2015, Ken Boon and several others occupied Rocky Mountain Fort and were visited by David Suzuki and Grand Chief Stewart Phillip. Hydro hit the occupiers with a $420 million SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation) suit for this “breach of the peace.”

Cox describes the passion and heroism of dozens of Peace supporters. A perfect symbol of the resistance is a life-size inflatable white elephant seen on the canvassing circuit. When Marc Eliesen was head of BC Hydro in the 1990s, he said, “Site C is dead.” Later he called it a “white elephant” and the description stuck.

It’s all very well to oppose Site C, but the main question must be answered. Where else are we going to get the 1,100 mw of power to “keep the lights on” as Christy Clark said, pushing the project to “the point of no return”?

Fortunately, answers abound, and Cox provides them.

First, demand for power in B.C. is not increasing. Site C power may cost $100 a megawatt/hour to produce and the surplus might have to be sold on the spot market for $30.

Second, consider solar power. The cost is decreasing but the government is not encouraging development.

Third, look at wind power. The Meikle project near Dawson Creek can power 54,000 homes. B.C.’s total wind capacity is estimated at 16,000 mw.

Fourth, B.C.’s potential geothermal capacity is about 5,500 mw.

Fifth, unused downstream benefits from the Columbia River Treaty would equal Site C capacity. For that we flooded the Arrow Lakes.

Sixth, there are unused spaces for additional turbines in the Revelstoke and Mica Dams with capacity equal to Site C.

Seventh, the Burrard Generating Plant in Port Moody is the cleanest standby natural-gas-fired plant on the continent: 950 mw.

Eighth, consider “pumped storage” with two small reservoirs at different elevations. Pump the water up when demand is low, and use the power when demand is high.

Why is the government not pursuing these alternatives? “The focus seems to have shifted to Site C. Everything else has fallen by the wayside,” says John Wright of Marmora Pumped Storage. And in the light of the BCUC report, it’s a mystery why the new NDP government has chosen to go ahead with Site C.

As Marc Eliesen said, “[Considerations that the BCUC] came forward with are such that no sensible rational person could take any other decision than to terminate Site C … a slam dunk.”

So hope springs eternal. “I’m planting a garden and ordering seeds,” said Arlene Boon.

“Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more.” (W. Shakespeare, Henry V)

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught drama for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and the Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Leave a Reply