Chapter Six

December 15th, 2016

Getting It All Done

The summons came just after lunchtime on August 23, 1941. “Miss Ravenhill” the anxious voice of Betty Newton sounded through the door of her room at the Windermere Hotel, “Dr. McGill, Major McKay and Mr. Moore are downstairs waiting for you.”

Alice Ravenhill’s mind raced. Even though she had asked for a meeting with officials from the federal Department of Indian Affairs, no formal arrangements had been made. “This is my chance to help Anthony Walsh in his career,” she said to Newton, “And Francis Baptiste too, of course.”

“Aren’t we supposed to refer to Francis as Sis-hu-lk, Miss Ravenhill?” Newton said hesitantly, hoping that Ravenhill would not snap back at her. “If we use his baptismal name, then people think he is French-Canadian.”

“Oh, of course,” Ravenhill snapped. “Now help me here, I don’t have a second to collect a note or Tale of the Nativity or anything else.”

What a pity, she thought, that Duncan Campbell Scott was no longer the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Scott had been so gracious and polished when they had met a few months previously on the occasion of the showing of the charts. And very supportive of her work, too, unlike Betty Newton and her father, who had refused to let Ravenhill show any of her needlework or Sis-hu-lk’s paintings.

Scott had referred to his twenty years of work with Indian Affairs as “dating from the time when it was still human.”

Harold McGill, the current Deputy Superintendent, was a medical doctor, ex-military personnel and municipal politician. It was rumoured that he had been appointed to the position because he was a golf chum of R.B. Bennett, the Prime Minister.

Ravenhill had met McKay, the Indian Commissioner for British Columbia in his Vancouver office in April of 1940. She had been surprised at his outspoken criticism of Walsh’s work at Inkameep. “He drew my attention to a fire screen in his office with an outline on doe skin of an Indian with drawn bow and arrow, asking whether it is not an illustration of your [Walsh’s] want of real knowledge of the Inkameep people, for the attitude is one never assumed when drawing a bow, etc.”

At this meeting, however, McKay spoke kindly in support of Ravenhill’s work. R.H. Moore, the Indian Agent in Duncan, completed the group.

Approaching the sunroom, Ravenhill could see her three visitors. “They sat in a row… with me confronting the trio as if a prisoner before his judges,” Ravenhill wrote to Anthony Walsh. Her first question was to Dr. McGill, “How many minutes can you spare?”

“Very few,” McGill answered shortly, and the other two men nodded in agreement. McKay added, “We’re going back by the p.m. boat, and we have other engagements.”

Ravenhill chose her words carefully, as she presented the Society for the Furtherance of B.C. Indian Arts and Crafts as a cooperative organization that tried to work with, not against the Indian Agents and school principals.

“I fell into no trap,” she wrote to Walsh. Her main proposal was the appointment of a “sympathetic man versed in our Tribal arts and temperament to visit each Reserve with the Agent,” to find adults who could accurately reproduce the crafts of the past and to have those crafts sold in small centres on the reserves. The man that Ravenhill had in mind was clearly Anthony Walsh.

“I have no funds,” was McGill’s reply to Ravenhill’s suggestion. Still, was there a glimmer of approval in McGill’s impassive expression when she linked the request to getting natives off Relief. The theme of economic independence always resonated with government officials.

In addition to economics, the three inquisitors tried to figure out if Ravenhill knew what was going on with Noel Stewart in Lytton.

“I showed the Lytton boys’ panel and elicited they were en route to St. George’s,” she reported to Anthony Walsh. “Dr. McGill and Major McKay tried unobtrusively to pick my brains as to what I knew, but of course I confined myself strictly to speaking of [Noel Stewart’s] interest in his boys and his work and his sense of the great responsibility which had devolved upon him.”

At one point McKay whispered to Ravenhill, “You must show evidence!” but what evidence was there to show other than the publications?

“I compressed all I could recall into forty-five minutes,” Ravenhill wrote to Walsh later. “It wasn’t easy without a single leading question and at most four brief comments.”

She had just enough time to ask her sister Edith to bring down Sis-hu-lk’s picture of “Deer” from her room. The three officials from the Department of Indian Affairs looked at in silence.

* * *

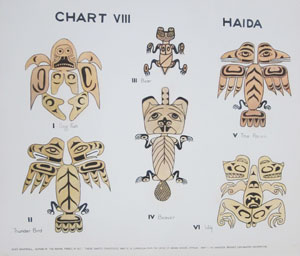

Alice Ravenhill wanted to create a set of Indigenous designs that would serve as exemplars for Indigenous youth and improve the quality of artwork in the schools and souvenir trade. In the spring of 1940, at the same time that she was organizing the new Society and the publication of The Tale, she set up a meeting to discuss her idea with Captain Gerald Barry, the Inspector of BC Indian Schools[1] for the Indian Affairs Branch [IAB]. She brought Betty Newton along to the meeting, both as a representative of the Committee and also for Newton’s artistic talents. Ravenhill described the meeting to Anthony Walsh as “quaint:”

[Captain Barry] knew nothing of my long work to arouse interest in Indian art or my study of the Tribes or the little book I prepared. So for an hour he talked, addressing himself entirely to Miss Newton.[2]

The matter of who was in charge was straightened out and by the end of the three-hour meeting, Ravenhill had convinced Barry of her knowledge of Indigenous arts and crafts and the need for some sort of visual reference for BC Indian Schools.

Ravenhill was firm in her belief that the artistic skills of all Indigenous peoples should be addressed separately: “To set a Salish man to carve after the method of the Haida or Tsimshian or a Nootkay [sic] woman to coil, and imbricate a Chilcotin basket, would be worse than [a]waste of time.”[3]

An informal agreement was reached whereby the end product would be a series of twenty large charts, 30 inches by 36 inches that depicted the various Indigenous cultures of British Columbia. Ravenhill would make the selection of the designs and Newton would draw them. A commission of one hundred dollars would be split between the two women. Ravenhill referred to their partnership as the Firm of Ravenhill and Newton, a play on the English art supplies company Winsor and Newton.[4] A handbook would be prepared to go along with the charts, but whether Ravenhill or the Indian Affairs branch owned it was not clarified.

Negotiating a partnership with Gerald Barry and the IAB was tricky. The Indian Affairs Branch was based in Ottawa, housed under the federal Ministry of Mines and Resources. When Ravenhill began her dealings with them, T.A. Crerar was the Minister in charge, and Dr. Harold McGill was the Director of Indian Affairs. On a simplistic level, interested people like Alice Ravenhill could see opportunities for social reform; on the bureaucratic level, any reform seemed impossibly complicated.

Given Ravenhill’s commitment to reform (whether for women working in the salt-curing industry in England or pupils in the Indian School system), it’s unlikely much would have dissuaded her from advocating for what she believed in — in this case, the value of having a set of Indigenous designs from which to create light industrial products.

She began, as usual, by writing to people she considered to have the most influence and decision-making power. In April, May and June of 1940 she wrote letters to local Members of Parliament and Senators from British Columbia asking them to write letters of support to the Indian Affairs Branch [IAB]. Each letter was tailored to the recipient. In the letter to Senator Henry Barnard, she referred to her association with the Royal Family through her Raven needlework design: “I have since been in correspondence with the Queen.”[5] She did not include the sentence in her letter to Alan Chambers, Member of Parliament for Nanaimo.

Captain Barry also wrote letters of support for the project. In a letter to Major D.M. MacKay, the Indian Commissioner for British Columbia, Barry pointed out the difficulties of having “authentic Indian designs” for children to use in schools, and the importance of having Ravenhill do the work:

[She] is very well known in Victoria, was an educational expert in the London schools, and is now 81 years of age… I do not like asking for this money but Miss Ravenhill is very frail and I do not wish to lose her services. There are very few if any others who could do what is needed in this way.[6]

MacKay repeated Barry’s theme in his subsequent letter to Robert A. Hoey, Director of Industrial Training for the IAB in Ottawa.[7]

In the meantime Ravenhill added Hoey to her writing schedule, emphasizing the economic potential in furthering Indigenous arts and crafts: “[A]ny step which might reduce the high cost of Indian relief seems worth consideration”[8] and her awareness of the difficulties of allotting the money in wartime: “Please do not brand me as blind to the many difficulties to be met or as utopian in my outlook.”[9]

Both Chambers and Barnard wrote to Dr. Harold McGill, promoting Ravenhill’s proposed project, as she had requested. By the end of June 1940, McGill announced that Ravenhill had been engaged to do the work.

The Firm of Ravenhill and Newton persevered through to the completion of the charts in January of 1941. Reactions to early viewings had been complimentary. As Ravenhill wrote in a letter to Anthony Walsh, Gerald Barry was so impressed “…that he rivalled the traditional lamb in meekness and almost painful realization that the hundred dollars I accepted for the Commission is almost an insult for work he values at many hundreds and feels should be at the British Museum or Ottawa.”[10] Plans were set in place to display the charts in Victoria before they were delivered to Major MacKay in Vancouver. Betty Newton’s father had offered a room at the Windermere Hotel for free and the date was set for February 24 and 25, 1941.

Ravenhill leaped at the chance to increase publicity for Sis-hu-lk and also make some money selling her own handicrafts at the display. A couple of days before the event, Reginald Newton decreed that commercial sales “would not be in good taste” at the display, and forbade Ravenhill to display anything other than the charts.[11]

Ravenhill leaped at the chance to increase publicity for Sis-hu-lk and also make some money selling her own handicrafts at the display. A couple of days before the event, Reginald Newton decreed that commercial sales “would not be in good taste” at the display, and forbade Ravenhill to display anything other than the charts.[11]

She was both crushed and livid and felt that Betty Newton had been behind the decision. She had already complained to Anthony Walsh that paying Betty Newton fifty dollars for what she called “merely copying designs” was too much.[12] Walsh, who had also received

Newton’s complaints, was probably glad to be in the South Okanagan, a few hundred miles away.

In a side project, Ravenhill had decided to make copies of the charts available to libraries, universities and colleges, and arranged with Gus Maves, a Victoria photographer, to make Panchromatic photos of them. She would put out the initial money and then recoup her expenses from expected sales. Maves wanted Newton to colour the photos, which upset Ravenhill even more. To Walsh, Ravenhill expressed her dismay at being unable to close the whole

episode with Newton: “It has made me feel smudged and is unique in a long life.”[13] Newton thought Ravenhill had been a “good sport” about the debacle of the display and had forgotten her disappointment. Ravenhill remained gracious in her acknowledgement of Newton’s work; but demoted her description as a “person with thorough artistic training and gifts”[14] to a “faithful copyist.”[15]

More than the perceived insult to her work, Ravenhill felt the loss of Newton as a possible protégé, and wrote to Gerald Barry:

A year ago I dared to hope I had found a real assistant in my Committee’s efforts; soon after the definite undertaking I made to which you refer [the Charts project] I was undeceived; and I had to face some hitherto unexperienced “scenes” (there is no other word) with the young lady and an unwise mother. It would be beneath my dignity to give details but ever since I have come unexpectedly across other foolish attempts to assume entire credit for copying (under my supervision and careful selection and direction) the figures on the charts, only entrusted to her because the preparation of the Handbook entailed much work on my part… It is after all so petty and foolish.[16]

The charts display brought Ravenhill into contact with Dr. Duncan Campbell Scott, “for many years Head of the Indian Affairs Office at Ottawa, a charming, polished old gentleman, who loves the Indians, and secured for those in B.C. in 1929 such small restitution for their lands as he could get in that pledge of a hundred thousand dollars a year for Industrial Training, which he hopes is paid!”[17] Was Scott that charming or merely a port in a storm? No doubt Ravenhill filed the incident away for such time as she might be able to use it to further her cause.

How much she agreed with Scott’s paternalistic attitude towards Indigenous peoples or his infamous and much-maligned statements about assimilation it is impossible to determine.[18]

At first the purpose of the charts was undefined. Clifford Carl, Acting Director of the Provincial Museum, asked whether they were intended to be distributed wholesale or if they would be better made up as lantern slides.[19] Ravenhill pursued her original idea of having copies of the charts distributed to all of the Indian Residential and Day Schools in B.C.

The role of the handbook she had prepared to go along with the charts was also vague. Corresponding exactly to the items on the charts, it comprised all of Alice Ravenhill’s knowledge on Indigenous arts and crafts. But only three copies of the handbook existed; Ravenhill had paid ten dollars each to have them typed. She kept one copy for herself, gave one to Gerald Barry, and sent one to Major MacKay in Vancouver, which was intended to go eventually to Ottawa.Gerald Barry had already suggested to Ravenhill not to mention the handbook to the Indian Affairs Branch. He could foresee himself using it to give little talks “to promote the revival of true Indian art” as a retirement activity in the near future. [20] Ravenhill was sure, however, that the handbook had been part of the commission, and she wanted to see it published as part of her whole endeavour to increase the visibility and economic viability of Indigenous arts and crafts.

Once again she enlisted support from well-known individuals to further her cause, beginning with her old friend, Sir Michael Sadler, now one of the best-known educationists in Britain. [21] It had been forty years since the two had worked together on the West Riding Education Committee in Leeds, Yorkshire. Sadler’s unconditional support of Ravenhill is evident in the letter he sent to Peter Sandiford, another well-known British educationist who held an academic position at the University of Toronto:

If the way opens, you might suggest to the Head of the office of Indian Affairs at Ottawa an inquiry into the advisability of encouraging the artistic side of education in schools for Indians in British Columbia. Miss Alice Ravenhill… has interested herself in the matter and is not a CRANK.[22]

Ravenhill sent the first annual report of the Society for the Furtherance of Indian Arts and Welfare to Sandiford, and he responded by agreeing with her stance on education: “You are quite right in insisting the education given to the Indian should take his environment and historical background into account.”[23]

In a subsequent letter to Sandiford, Ravenhill described the public attitude towards the Indigenous peoples of British Columbia as one of “contempt:”

… of which the result is a painful inferiority complex and mental deterioration among its objects. Yet they possessed great qualities before the coming of Europeans broke up their very complex social and religious organization and crushed their high level of artistic skills, which should have been preserved as a background of Canadian culture.[24]

Sandiford forwarded Sir Michael Sadler’s letter to Dr. Harold McGill, stating that anything that could be done to strengthen Ravenhill’s position would be “greatly appreciated by all Miss Ravenhill’s friends.”[25]

McGill’s response indicated a substantial lack of understanding on the part of IAB regarding Ravenhill’s cause. He dismissed Ravenhill’s references as “altogether too pessimistic and scarcely justified by conditions on Indian reserves in B.C.” [26] He pointed out that IAB had just opened the Alberni Residential School at a cost of $170,000, which to him proved that the Department was working to improve learning conditions. In addition to failing to address any of Ravenhill’s concerns about art education, McGill’s response confirmed the negative attitude of the IAB to any endeavours that involved money. This could be attributed to the pressures of the war effort to some extent, but not completely.

Despite all the support that Ravenhill garnered for the handbook, events over the next few months precluded any likelihood of the IAB publishing the book. McGill had made the mistake of telling Ravenhill that the Minister for Indian Affairs might discuss the charts with the National Art Gallery or Museum.[27] Ravenhill seized upon the idea and immediately wrote to Ottawa suggesting that the handbook be discussed as well.

In an effort to speed up the process, she sent her own copy of the handbook to McGill, but when she received no acknowledgement of its arrival, she wrote repeatedly and urgently to R.A. Hoey in an effort to locate it. Finally Hoey asked MacKay in Vancouver to help find the missing copy: “I must express regret that I had to trouble you in respect to this matter, but I could see no other way of discouraging Miss Ravenhill in her anxiousness to correspond constantly with the Department.”[28] MacKay must have pressured Barry, who in turn suggested to Ravenhill that she should restrict her correspondence in the matter of Indian arts and crafts with Department officials.[29]

Ravenhill’s reaction is not recorded. The missing copy turned up on her desk shortly thereafter. Had it been there all along? Had Gerald Barry sneaked it in?

Ravenhill’s letter writing campaign created enough disturbance that she was granted an unexpected visit from Dr. McGill on his Western Tour in August of 1941. He was accompanied by Major MacKay from Vancouver, and R.H. Moore, the Indian Agent in Duncan. With no prior notice, they descended upon her at the Windermere Hotel, as described at the start of this chapter.[30]

Although the charts and handbook project most likely provoked the visit, Ravenhill spent most of the time describing the work of the Society for the Advancement of Indian Arts and Welfare and advocating that a supervisor be hired to work with bands and reserves to promote arts and crafts. This had been a point of discussion in IAB in 1939, when Harold McGill sent a memorandum to the Deputy Minister of Mines regarding the appointment of a Director of Handicraft Projects for British Columbia.

At that time, McGill had indicated that he did not support such an appointment and referred to a letter from Mr. MacKay, the Indian Agent in Vancouver, who wrote dismissively: “[I]t is comparatively easy to over-emphasize the value and significance of Indian Handicraft work as a factor in the reduction of unemployment relief costs.”[31] Ravenhill might just as well have saved her breath in promoting the economic benefits of Indigenous handicrafts with the IAB.

She continued to hope that the handbook would be published. In her last request in September of 1941, Hoey replied with a list of other IAB financial commitments in Central Canada such as a reconstruction of the Church of the Mohawks and restoration of the birthplace of Pauline Johnson at Brantford. He also listed cuts that had been required by the war effort; for example, the school terms at the Indian Day schools had been reduced from ten months to nine.[32]

In a letter to MacKay that was intended to set the matter at rest, Hoey complained about the large number of letters that IAB had received from Ravenhill, while also conceding that the many visitors to Indian Affairs who had seen the charts “were appreciative in their remarks concerning their beauty and artistic worth.” Hoey ended the letter by stating that he was “frankly of the opinion that this is a very inopportune time to ask for the funds necessary to either print the handbook or reproduce the charts.”[33]

The IAB thereby gave up any claim to have the handbook published. Ravenhill was left with her manuscript. She managed to complete an excerpted version for The Beaver in 1942 that included many sketches from the charts project (Betty Newton’s work was not acknowledged in any way in the article). [34] Ravenhill credited Harlan I. Smith of the National Museum at Ottawa with originating the idea that “early Indian arts of Canada might well serve as a suitable starting point for manufacturers in the production of distinctive Canadian designs,” and she outlined in sophisticated detail the characteristics of Pacific Coast art and blamed the tourism industry for its deterioration into what she termed cheap replicas.[35]

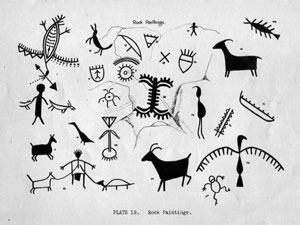

Although the charts and handbook had been completed within a year of Ravenhill’s receiving the commission, publication did not occur until 1944 as A Cornerstone of Canadian Culture by the B.C. Provincial Museum. The number “33,000” had appeared several times in Ravenhill’s correspondence about the handbook. It was the exact number of words that she had used in her detailed descriptions of every single artifact that Betty Newton had drawn and coloured.

Ravenhill was careful to explain her use of the term “primitive” to describe the Indigenous art of B.C. “The word popularly carries the idea of that which is crude and imperfect: whereas in modern parlance the meaning is restricted to that period of a people’s existence before methodical records were made or preserved.”[36]

She also made a concerted effort to give as much information as possible. For example, one 45-page section on Mythical Beings and Crests included compilation of information from five different tribal groups. All sources were diligently referenced with a large number of them attributed to W.A. Newcombe, who had allowed Betty Newton to sketch items from his personal collection. Ravenhill made contemporary references as well; in discussing D’Sonoqua, wild woman of the woods, she recalled for readers Emily Carr’s vivid word pictures in Klee Wyck (1941).

Published in 1944 as Occasional Paper Number 5 of the British Columbia Museum, A Cornerstone of Canadian Culture consisted of 103 pages of text and 20 illustrative plates with a foreword by Carl, who had succeeded Kermode as museum director. The museum’s 1944 report acknowledged the success of the publication in publicizing the work of the museum: “The Occasional Paper by Miss Alice Ravenhill, which presents a brief outline of the arts, crafts, and legends of the native tribes, has been in such demand since its appearance that the supply of copies has become exhausted; a second issue is planned for 1945.”[37]

By the time of the publication of A Cornerstone, a new Indigenous artist had come upon the scene. In August of 1941 George Clutesi called upon Ravenhill, bringing along a few of his paintings. Ravenhill found Clutesi more sophisticated and accustomed to sell his pictures than Sis-hu-lk. “He told me he had been forbidden to draw or paint at school, but it would come out, and I surmise he now makes a good deal from sales to tourists.”[38] She found his pictures “richly imaginative” and arranged for Arthur Pickford to visit Clutesi on his next visit to Alberni.

Ravenhill also wrote to ask the Indian Agent at Alberni for a recommendation for Clutesi: “Will you tell me if he supports himself by his paintings and something of his background and standing at Alberni. My committee desires to help forward such native talent as he possesses but desires also to proceed with caution.”[39]

She wrote a similar letter to Clutesi with the same questions, and explained the aims of the Society: “We want to show that the Indian gifts of drama, painting, carving, weaving, songs, dances, are all contributions to Canadian Culture and should be encouraged and preserved.”[40] The Indian Agent wrote back with a fine recommendation for Clutesi,[41] and Ravenhill was pleased that the young man was said to prefer painting to fishing.[42] She had also enjoyed Clutesi’s surprise that she knew “all about the preparation, fastings, the duties of the Chief, etc. etc.”[43]

Events like meeting George Clutesi helped get Ravenhill through moments of despair about her advancing age, the inactivity of the Committee, and the health of her siblings. Her brother Horace had died in October of 1941 after a painful and costly operation. Given her own frail health, she felt like she had undertaken a next-to-impossible amount of work, as she told Daisy Millar:

Only yesterday my doctor, no alarmist, told me again he supposed I realized what is coming to me if I continue at this pressure; yet, candidly, if I withdraw the Committee here will just die out; even did I take a brief holiday how could correspondence accumulate during the interval. My committee requires that all Minutes to be written by hand, not typed; arrears to be written for the first year I have only notes, no regular Minutes, the rush was too great; I cannot see my way to do this.[44]

She was particularly annoyed that she could no longer waken at 5 a.m. for two hours of undisturbed work, as she had done her whole life.[45]

What made Ravenhill continue such an uphill battle? Was it pride? Was it her rock-solid commitment to social reform and education? Or was it her eight-year old self, taking the weight of the world on her shoulders?[46]

Even though she stated that she wanted to cut down the time she had committed to the Society, she also did not want to give up control. For example, Arthur Pickford agreed to take over the correspondence with the schools and Indian Agents, but she did not always like what he did. As part of the Inkameep children’s visit to Victoria in June of 1941, she wanted to have an exhibit of their costumes and art; but Pickford had obtained masks from the Provincial Museum.[47] Ravenhill, with her intuitive understanding of the need to show the children’s actual work, went ahead and organized the shipping of the desired items from Oliver to Victoria. Thus she achieved more publicity, but caused herself much more stress and strain.

The founding of the Okanagan Society for the Revival of Indian Arts and Crafts in the spring of 1941 was encouraging. Albert and Daisy Millar, Oliver residents, had joined with Anthony Walsh in starting the branch society with fourteen members. The Millars were British immigrants with an interesting background: Albert was an engineer and they had lived and worked in Venezuela for a few years before taking up fruit farming around Oliver.

Daisy Millar was a skilled and inveterate fund-raiser; she had declined to sell Sis-hu-lk’s picture of “Running Horses” at the Victoria exhibit where it would probably have fetched eight or ten dollars. Instead, she raffled it off in Oliver, her sister won it for $58.50, and then turned around and re-raffled it for £177, all of which went to the Lord Mayor of London’s fund for bombed Britons.[48]

Ravenhill was overjoyed that a new Society had started:

I cannot tell you how our tiny farthing dip feels its light increased by the addition of your powerful candle. We know you will become a tower of strength to the movement in which we are all interested…. To be truthful, Victoria has not a spark of interest in our objects; get rid of these cumberers of the ground is the attitude.[49]

Ravenhill requested that the Okanagan Society take over the handling of Sis-hu-lk’s affairs. “It is more than I can manage at this distance…,” she told Millar. “His pictures always seem to be in the wrong place; here when wanted at Inkameep and at Inkameep when wanted here.”[50]

Still she found it hard to withdraw. Millar had mentioned that Lawren Harris might make a trip to Oliver, and Ravenhill asked to be kept informed of this possibility. To have two members of the Group of Seven interested in the work of Anthony Walsh’s students was an incredible coup and testifies to the reach and influence of Walsh and Ravenhill and the work of the Society for the Furtherance of Indian Arts and Welfare.

Ravenhill tended to emphasize Baptiste (Sis-hu-lk) over other artists but Millar thought that Johnny Stalkia had the potential to “outrun Sis-hu-lk if he keeps to his art.”[51] The drawing and painting talents of several young girls were also evident; eight-year old Edith Kruger, for example, had two drawings in a 1938 group submission to the Royal Drawing Society. She and Bertha Baptiste won Silver and Bronze Stars respectively in their final submission to the Royal Drawing Society in 1942.[52]

The Okanagan Society included a wider variety of people than the Victoria group, and encouraged local Nk’Mip band members to join. The mix of people included two local writers, Elizabeth Renyi[53] (sometimes spelled Rennie) and Isabel Christie MacNaughton.[54] These two young women were very interested in Indigenous legends; a local Salish woman named Josephine Shuttleworth had told MacNaughton many local legends that the latter wrote up and had published in the Pencticton Herald.

Renyi and MacNaughton collaborated on a number of plays with Anthony Walsh, such as “Why the Ant’s Waist is Small,” and “The Crickets Must Sing,” performed at local concerts and on CBC Radio. The Okanagan Society was much more oriented to the local community than the Victoria group; for example, they gave a Christmas tea at the Inkameep School to meet the women of the Reserve, and put on a big party for the children.[55]

Daisy Millar also initiated a Christmas card fund-raising project for which she borrowed some plates of Sis-hu-lk’s illustrations for The Tale of the Nativity.[56] Ravenhill thanked Millar for sending her some of the cards but as usual had a suggestion for improvement. “A constant quibble at the purchase of those you sent us for sale was that showing a skunk, which people thought a highly unpleasing subject to send with good wishes to friends at Christmas!!”[57] It’s not known whether Millar complied.

A Vancouver branch of the Society for the Furtherance of Indian Arts and Welfare came close to starting in September 1941. Here it also had a distinctly artistic and literary impetus. Anthony Walsh started the process by meeting with Mildred Valley Thornton,[58] a Vancouver writer and artist, and De Lisle Parker, who wrote an arts column under the name “Palette.” Walsh made one of his dramatic presentations to the Women’s Canadian Club[59] with nine hundred people in attendance, and met Nellie McCay, the founder of the Vancouver Folk Festival, who wanted to put on a display of the Inkameep children’s art at the Festival.

Walsh also spent an evening with Lawren and Mrs. Harris who, he thought, would not belong to the committee even though Harris had helped Sis-hu-lk obtain a fellowship to attend the Conference of Canadian Artists in Kingston, Ontario, and had offered to pay his additional expenses.[60] In a letter to Walsh a couple of months later, Ravenhill remarked upon the progress of the Vancouver committee. Thornton, she wrote, was wise in taking time to form the committee and noted the interest of certain UBC professors, such as Dr. Walter Sage, “a man of stability and experience.”[61]

Still, Thornton had been somewhat discouraged by the Vancouver attitude “which fails to see reason to support BC Indian artists or arts because all such ‘push’ should go to ‘Canadians.’”[62] This use of the word “Canadians” to exclude Aboriginal peoples suggests the currency of the widely held attitudes that Ravenhill had worked hard to dispel in Victoria.

In the end, all was for naught: as Ravenhill wrote to Walsh. “Vancouver Committee having really organized with great promise the first week in Jan. [1943] melted in two days when Prof Topping notified Mrs. Thornton that the four UBC professors withdrew their support.”[63]

Ravenhill continued to use Walsh as a sounding board, commenting on the Victoria Society Committee that while Flintoff and Pickford were working on the bylaws, the other five or six were “deadwood. Such are Victoria committee traditions.”[64]

She also considered that the rationing part of the war effort in Victoria was inadequate. “Most people seem to spend lavishly in Victoria; entertaining is continuous and on costly lines; even the Duke of Kent asked Mrs. Hamber if she often entertained on the lines he found at Government House, saying he had had no such food for over two years!”[65]

This changed rapidly after the Pearl Harbor airstrike on December 7, 1941, which Ravenhill thought had finally awakened Victoria to the fact that there was a war on. Arthur Pickford resigned from the Committee to do war work; Betty Newton took a high-paying war job.[66]

Ravenhill began to focus on pedagogical methods in addition to her usual topic of economic development. Having seen the effects of passionate and caring methods of teaching upon Indigenous children, she passed on her ideas about teacher education to Anthony Walsh. “To me the first obstacle to overcome is the attitude of the teachers who are ‘set’ in Training College methods and as Captain Barry has explained to me on more than one occasion, know nothing about the past ‘skills’ of these people and are deficient in interest, indeed, lack desire to advance them as we do.”[67]

A related topic concerned the direction that education should take in Indigenous schools. Finding time to do art in the residential schools was very difficult because the pupils spent only half-days on schoolwork, and the other half doing farm or household chores. Stewart’s pupils were only allowed to draw for one hour on Friday afternoons. “How they enjoy it,” he wrote to Ravenhill, “They seem to be all doing ‘bucking horses’ or such.”[68] Ravenhill wrote to R.A. Hoey to suggest that more time be spent in the arts. In his reply, Hoey referred to a conversation he’d had with Dr. Diamond Jenness that seemed to be setting IAB policy:

Dr. Jenness is definitely of the opinion that our Indian day and residential schools should provide instruction in practical subjects such as boat-building, auto mechanics, carpenter work and elementary agriculture for boys and sewing, dressmaking, crochet work, fruit preserving and elementary domestic science for girls. Inspector Barry will be in a position to give you a good idea of the attempts we are making to carry out this policy in our educational institutions.[69]

Ravenhill wrote to her usual correspondents to complain. The ever-cheerful Noel Stewart tried to reassure Ravenhill: “Don’t worry over Mr. Hoey’s statement. We’ll prove to him different yet. I am told he may travel West this year, so he’ll call on us and I’ll do my best to let him see us in our finest array.”[70] To Albert Millar, Ravenhill commented on Jenness’s expertise in the topic of education:

I have received a letter from Mr. Hoey at Ottawa informing me of a long conversation with Dr. Jenness, chief of the Anthropological department at the National Museum in which they agreed that the only subjects desirable in Indian schools are mechanics, carpentering and elementary agriculture for boys and domestic science, fruit bottling and crochet work! [emphasis in original] for girls. I have known Dr. Jenness a quarter of a century, and while recognizing his great ethnological abilities, I can truthfully say he has no sense of any form of art; in vain I tried whenever he was out on this coast to arouse even a dim perception of the unique artistic gifts of our BC Coast Tribes; so can estimate the worth of his opinion from long knowledge of his personality. All modern real educationalists are alive to the fact that to repress natural gifts is to warp the individual’s moral development; further we want to convert our Indians from liabilities into assets in a proportion of their numbers; and otherwise feel our responsibilities towards them as our fellow Canadians.[71]

The Committee, most likely led by Ravenhill, took a few weeks to respond to Hoey’s letter. The first sentence expressed regret about the letter and especially in Dr. Jenness’s opinion on curriculum limitations. Using the same reference to modern educationalists as in the letter to Millar, the committee reiterated the benefits of permitting children “a certain period for the free expression of their own ideas, whether pictorially in poetry, dance or drama.”[72]

The mention of crochet work had particularly incensed the Committee — again, most likely only Ravenhill: “Why [do] you advocate so futile an occupation as crochet work in Indian schools, when girls knit, weave and embroider with outstanding skill[?].” Finally, the Committee suggested that the inclusion of Jenness’s opinion in curricular decisions was faulty, using gentler words than in her letter to Albert Millar:

I may add I have known Dr. Jenness for 27 years…. while feeling honoured by acquaintance with so highly gifted a man in certain scientific lines, I have had to realize that on the artistic side he is liable to overlook or fail to appreciate what affords evidence of skill recognized by others whose abilities lie in other directions.[73]

Ravenhill was not finished with the topic. A few months later, Madge Watt, an old acquaintance of hers from Women’s Institute days, sent her a copy of a report from the Associated Country Women of the World international conference in Ottawa, of September of 1941. Ravenhill zeroed in on the following quotation:

The display of Indian Handicraft brought to the attention of all those attending the convention the fact that the Indians of Canada have a heritage well worth fostering and promoting – artistic talent, deft fingers, and infinite patience. “We believe,” said Mr. Hoey, “that Canadian Indians have a real contribution to make to the arts and crafts of the Dominion.”[74]

Ravenhill used Hoey’s quotation in a paper she prepared in October 1942 for IAB entitled, “Suggestions on the Encouragement of Arts and Crafts in the Indian Schools of British Columbia.”[75] She opened with an appeal to parents and teachers to ensure that all boys and girls contributed to national welfare and prosperity, and she drew particular attention to the “innate artistic and other abilities of children in our B.C. Indian schools.” “One of our tasks as teachers is to devise ways and means of bridging the gap between the rich artistic past of our Indian charges and the drab present of today.”

Teachers, she suggested, could obtain examples of traditional Tribal designs and make a start by putting one up on the blackboard each week. Stories could also be a useful form of stimulation, with their focus on the children’s immediate surroundings. She pointed out that the required use of English was a form of repression that denied the students’ use of their own ”picturesque and dramatic” languages. Following Hoey’s quote were several pages of suggested illustrations, books, materials, and projects.

The Okanagan Society produced “Native Canadians – A Plan for Rehabilitation of Indians” that was years ahead of its time in political activism. Photo by author.

The Okanagan Branch used Ravenhill’s “Suggestions” to spin off a more politically-inclined paper in 1944, “Native Canadians: A Plan for the Rehabilitation of Indians,” which was submitted to a Federal committee on reconstruction and re-establishment in Ottawa.[76]

The cover bore an evocative illustration by Sis-hu-lk of a teepee against a setting sun with smoke rising from a campfire. The Introduction to “Native Canadians” acknowledged the “rich heritage of our native Canadian people through the astonishing renascence of Indian arts, the outer sign of an inner renascence of the almost vanished Indian spirit,” and the body of the paper included discussions of the approach of Canadians to the Indian; analysis of deficiencies in present conditions; improvements in the United States in the previous ten years; short-term improvements suggested for Canada; and long-term suggestions for solution of the whole problem.

“Native Canadians” also noted the great interest into delving far into the past through archaeological and anthropological studies and the fact that the Indigenous population was still living, in many cases, in deplorable conditions:

Indians have practically no means of making themselves self-supporting except in certain cases as labourers and domestics in wartime, and they have no rights as citizens anywhere in the world [emphasis in original]. They appear to be administered by a Department whose policy often reflects neglect and parsimony due to totally inadequate financing from the government…. The responsibility is ultimately that of all Canadians and therefore we are presenting this brief.[77]

The brief used the 1942 Annual Report of the Indian Affairs Branch for an empirical analysis. It went far beyond the rhetoric of Ravenhill’s Suggestions, which the brief mentioned as a means of raising the status of Indigenous schools. It began with malnutrition and semi-starvation conditions outlined in the IAB report, and asked why nothing was being done. It pointed out that the IAB report gave the number of Indigenous enlistments in War Services, but neglected to indicate the high number of would-be soldiers who had been rejected because they were malnourished. Schools were critiqued for not having qualified teachers, despite the IAB statement that it was wholly dependent on the provincial normal schools to supply teachers.

The Okanagan Society report also asked why no attention was being paid to higher education, since this had been promised in 1927. Employment was also a topic: “When will it be realized that welfare work ceases as jobs are provided whether for Indians or whites?” In conclusion, the Okanagan Society stated:

The Department’s whole attitude is… nakedly revealed: Indians are not to be educated to their ability and aptitudes, to take on the great tasks that this world waits for; they are not to take their place among other inhabitants of Canada for whom upward paths are not closed; they are to remain “labouring classes” as the highest ideal [emphasis in original]. We as responsible citizens absolutely reject this attitude to our fellow human beings. Indians are Canadian people and we shall not rest until we have made every possible attempt to bring their plight to the Government’s attention.[78]

Finally, the report noted the inadequacy of grants in residential schools, especially for food and clothes, of only 40 to 47 cents per day per child. “Due to this cause the children have to spend much time planting and growing food, instead of being in the classroom, and the under-nourishment and poor clothing naturally lead to tuberculosis in later life besides keeping the children backward in their school work.”[79]

The Okanagan Branch submitted a second brief to the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons appointed to examine and consider the Indian Act in 1946.[80] The brief made many references to the 1944 Native Canadians report. Its overall tone was advocacy of “total emancipation of the Indian,” with a call for Indigenous voting rights and fair treatment of returning servicemen. The brief asked for a survey of all Reserves to see if they could support the present Indigenous population, and also bring to light, health, and sanitary conditions, educational and recreational facilities, industry, vocational training possibilities, and finally the “best ways and means to foster revival of native arts and crafts.”

The 1946 brief also devoted a large section to education and provided examples of the failure to assist Indigenous youth in post-secondary efforts. Describing the education system as “third-rate,” the brief suggested the transfer of Indigenous education to provincial control “in order to gain some equality for the Indians in the places where they live.”

Some oddities were pointed out: Indigenous persons on small Reserves were not allowed to own their own road grading equipment, and therefore those living in isolated places were unable to receive nursing care because their roads were impassable. The brief disputed the power of Indian Agents: how were they appointed? Did they receive any training? How many of their dictatorial powers were necessary? Enfranchisement was at the heart of the brief: “There is no reason why Indians should not be given the vote immediately, without any qualification or reservation whatsoever.” They had after all been given the vote in the United States in 1934. Other Canadians must be prepared “to receive Indians on a basis of equality.”[81]

The Okanagan society presentation was part of a three-year process in which briefs and representations were received from First Nations, missionaries, schoolteachers, and federal government administrators. A 2011 pamphlet published by the Ministry of Indian and Northern Affairs states that the committee hearings were one of the first occasions where Indigenous Canadians were able to address parliamentarians directly instead of through the intermediary of Indian Affairs,[82] but the process had little effect. “Despite the extensive hearings and the committee’s report, a 1951 amendment did not bring sweeping changes to Indian policy or greatly differ from any previous legislation.”[83]

The Okanagan Branch of the Society was devastated by the resignation of Anthony Walsh to take a new job with the Canadian Legion War Services in early 1943. Ravenhill was more prosaic than most about his leaving: “About yourself I am sure you are right — your abilities and experience should be contributing to War Service.”[84]

Meanwhile the war effort was heating up. Meal service was cut off at the Windermere Hotel in April 1943, and Ravenhill and her sister had to cook for themselves for the first time in years. Although Anthony Walsh had moved on, she still confided in him as a friend:

As we are too old to turn out early and late we have to get breakfast and supper in my bedroom, starting housekeeping with 2 cups and 2 saucers! We had to buy essentials from Woolworths and keep our supplies in the bathroom attached to this, to which we had to move at increased cost. But the “getting” teems with little inconveniences and exertions which tell hardly upon old folks of 83 and 84. We go out for our midday meal, and are managing fairly well, but the difficulties of overcrowded stores, many of which close two or even more days in the week from want of service or shortage or supplies, adds “chores” which add to fatigue. [An] unprecedented cold spring means the wearing of even winter garments… an extra small anxiety as woolen undergarments are no longer to be had here or at Winnipeg. All this will sound to you to savour of grumbling; actually I think it springs from my great desire to complete some work on a booklet of BC Indian folklore and another on our BC tribes and their organization for Dr. Carl.[85]

Ravenhill also kept Walsh informed of new developments with the Society. Dr. Carl had met with Major McKay who made it clear that no official support for Indigenous art education would be possible while the war lasted. Ravenhill questioned if any support would exist after the war either: “[The IAB] have no anthropological insight into the temperament of our Indians; the one idea impressed now on teachers is to civilise the children and turn them with all speed into ‘whites.’”[86]

Dr. Carl had gleaned from his talk with McKay that the Inkameep parents had petitioned for a more thorough grounding in arithmetic, and that this might have been one of the reasons for Walsh’s leaving. Ravenhill passed on to Walsh information from Daisy Millar that the new teacher, a Mr. Kierman, saw nothing at all attractive in Indian art, and Millar mourned the abolition of all that Walsh had worked for. “Perhaps I do wrong to bother you with all this,” Ravenhill wrote to Walsh, “but at times I find it hard not to lose heart.”[87]

Anthony Walsh had definitely said goodbye to Inkameep. In a memoir, he described the children of the Day School as being caught between the old ways and the new, and he questioned the futility of expending energy that would come to nothing. “Among this small group that had brought such joy,” he wrote, “…a number died tragic and premature deaths. They became broken in spirit and the light of gladness that had once lit their eyes became glazed. But for a few brief years they had experienced happiness.”[88]

After the war, Walsh spent a few years travelling throughout the United States and parts of Canada. He spent six months in Vernon, BC and participated in the First Conference on Native Indian Affairs at UBC in 1948, and the following year moved to Montreal.

Then, echoing Ravenhill’s complete change of focus in the middle of her life, Walsh began a new phase of his own life, establishing the Benedict Labre shelter for aged and homeless men in 1952 and taking a vow of voluntary poverty. He received an Honorary Doctor of Laws from Concordia University in 1975 and was made a member of the Order of Canada in 1989.[89]

Lisa Smith suggests that the failure of the Inkameep initiative to continue after Walsh’s departure indicates that its success was largely due to his extraordinary efforts.[90] When A.J. Dalyrumple of the Vancouver Daily Province travelled through Osoyoos in 1947, he reported that Walsh’s male ex-students were all playing pool.[91]

But others were more active. Gertie Baptiste, one of the most promising young artists, according to Chief Clarence Louie of the Osoyoos Indian Band, was sent to a regional residential school but telephoned her mother and managed to convince her to take her back home.[92] Francis Jim Baptiste went on the rodeo circuit, where he had much success: his niece, Virginia Baptiste, said the excitement of the rodeo kept him on the road for twenty years.[93]

Back on the coast, Ravenhill continued to promote Indigenous arts and crafts. She met with the Sisters of St. Ann’s to teach them how to reduce tribal designs for use in various items, and found them delightful to work with.[94] When she was asked to give a ten-minute talk at the Canadian Authors’ and Librarians’ Association, she asked Daisy Millar to send some masks and costumes from Inkameep for a small display.[95] She also included some of Sis-hu-lk’s pictures from a Vancouver Art Gallery display for the Authors’ Association and noted that the pictures looked “startlingly outstanding against the rich mahogany panelling of the Provincial Library.”[96]

She had written to request a meeting with J. Murray Gibbon, President of the Authors’ Association, but when it came, she was sadly disappointed:

When at very long last [Gibbon] was led reluctantly to speak with me he was grumpy to the point of rudeness, said he had no interest in Indians or anything to do with them; I made him wait a moment while I mentioned the possible use of SSH’s work for CPR posters; he then walked away. Mr. Pickford phoned to me yesterday that the old man softened the crust after a little in the evening, looked with care at the lad’s work and gave him his address.[97]

Ravenhill felt equally disappointed in her talk to the Authors’ Association the next day. She was given only ten minutes at the end of the day to talk about the Society and Indigenous art, and found the circumstances paralyzing, “even to an old hand like myself.” The only good thing anyone had said about her talk was that her voice carried to the most remote corner: “I felt as usual that I failed.”[98]

Ravenhill placed much hope in a request for Native designs from the dominions and colonies of Great Britain made by the Manchester Cotton Board in the fall of 1941, even mentioning it in her Beaver article. She spent a number of months preparing samples of designs that conformed to commercial trade lines, as she understood them. Perhaps her grandfather Thomas Pocock’s successful cloth manufacturing business had left her with some residual knowledge, and certainly, interest. The final samples were sent to James Cleveland Belle, Director of the Cotton Board’s Colour, Design and Style Centre. Ravenhill described in great detail to Noel Stewart how she made the samples:

The designs I sent to Manchester I mounted on the Cards which back blocks of Quarto paper; I had no guide beyond my own ideas! Under each design I put its significance; on each card was a clear numeral and the address of our society; in your case the school, etc. I faced each card with tissue paper to protect it and give a professional air. I sent two “all over” designs of small figures such as are printed on summer fabrics, two or three sheets of borders reproduced from beadwork or painted designs on native costumes or possessions, drawn somewhat larger than the originals; showing adaptation to curtain borders, table cloths, etc. Others had separate figures arranged to suggest designs for cretonnes cushion covers, or for embroidery on costumes, fashionable at present. I sent a dozen such cards in all carefully packed in thick card outer case and strong paper. I enclosed a list of contents, sender, names of the artists, etc; and sent a covering letter by the same mail explaining how I came to send them having noted the desire of the Cotton board to receive designs from the Dominions and Colonies by NATIVES. It will be three months before I can hear if they reach England; but I feel it is most well worth the trouble; such a chance for our BC Indians.[99]

Ravenhill waited anxiously for an answer, but it did not arrive until the middle of March 1942. In it, Cleveland Belle thanked her for the samples and mentioned the war effort, the need for utility clothing, and women working outside the home. He found the designs interesting, he said, because most British designers were in the forces and few new designs were then available in Britain.[100] But he gave no word on whether the B.C. Native designs might be used.

Ravenhill immediately sent Belle’s letter on to R.A. Hoey, adding: “I confess to a tinge of pride that single-handed, I have secured this recognition of our Northwest Pacific Tribal Art.”[101] Unfortunately nothing further came of the request from the Cotton Board.[102]

But the age clock was ticking for Alice Ravenhill. Her active life came to an end in January 1944 — but not her active mind.

[1] AR to AW, n.d. [c. March, 1940]. Alice Ravenhill fonds. Box 1 – File 8, UBCSC

[2] Ibid.

[3] AR to Alan Chambers, Member of Parliament for the Nanaimo riding. 12 June 1940, Library Archives Canada [LAC] RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[4] AR to Walsh, 23 October 1940. Box 1 – File 8, UBCSC. Thanks to R. Mackie for noticing this.

[5] AR to Senator Barnard, 7 May 1940, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1. Ravenhill had received a letter from Elizabeth, Queen Consort’s lady-in-waiting. It was an exaggeration to say she was in correspondence with the Queen.

[6] G. Barry to D.M. MacKay, 5 May 1940, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[7] D.M. MacKay to R.A. Hoey, 28 May 1940, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1. Robert Hoey was a former Methodist minister and a federal MP from Manitoba for the Progressive Party from 1921 to 1925. His old friend T.A. Crerar brought him into the IAB after he was defeated in a provincial election in 1936. See R.S. Sheffield, The Red Man’s on the Warpath: The Image of the “Indian” and the Second World War (UBC Press, Vancouver, 2004, p. 190). Some more insider knowledge of the intertwined connections in the IAB might have helped Ravenhill’s cause, attuned as she was to relationships.

[8] Ravenhill to Hoey, 12 June 1940, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[9] AR to Barnard, 12 June 1940, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[10] AR to AW, 22 November 1940, Box 1 – File 8 – UBCSC

[11] Betty Newton to Anthony Walsh, n.d. Box 1 File 8 UBCSC

[12] AR to AW, 24 February 1941, Box 1 – File 8 UBCSC

[13] Ibid.

[14] AR to AW, n.d., Box 1 – File 8 UBCSCL

[15] AR to McGill, 5 March 1941. LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[16] AR to Gerald Barry, 29 March, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[17] AR to AW, 31 March 1941. Alice Ravenhill fonds. Box 1 – File 8 – UBCSCL

[18] For more about Scott and the controversy that surrounds his tenure as Director of IAB, see Mark Abley, Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott. Madeira Park, BC: Douglas & McIntyre. 2013.

[19] G. Clifford Carl to AR, Feb. 21, 1941, GR 0111, Box 16, File 27, BCA

[20] Gerald Barry to AR, 24 February 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[21] J.H. Higginson. “Michael Ernest Sadler (1861-1943).” Prospects: The quarterly review of comparative education, 24, 3 / 4, 1994, 455-69. Paris: UNESCO. http://www.ibe.unesco.org/publications/ThinkersPdf/sadlere.pdf

[22] M. Sadler to P. Sandiford, 16 December 1940. LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919,File 41203-1

[23] P. Sandiford to AR, 6 February 1941, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[24] AR to P. Sandiford 31 January 1941, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[25] P. Sandiford to H.W. McGill, 24 February 1941. LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[26] McGill to Sandiford, 1 March 1941. LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[27] McGill to Ravenhill, 7 April, 1941, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[28] Hoey to MacKay, 19 May, 1941, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[29] Barry to AR, 29 May, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[30] A fictionalized account of the meeting introduces this chapter. References are as follows: AR to AW, 23 August, 1941, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL; AR, Notes on McGill meeting, n.d., Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, File 17, BCA

[31] H. McGill to Deputy Minister, IAB, 21 August, 1939, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[32] Hoey to Ravenhill, 15 September 1941, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[33] Hoey to MacKay, 15 September 1941, LAC RG 10, Vol. 7919, File 41203-1

[34] The Beaver, now Canada’s History, began as a company newsletter published by the Hudson’s Bay Company out of Winnipeg. See http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/the-beaver-gets-a-new-name-1.865851

[35] Alice Ravenhill, Pacific Coast Art, The Beaver, 4-9, September 1942.

[36] A. Ravenhill A Cornerstone of Canadian Culture: An Outline of the Arts and Crafts of the Indian Tribes of British Columbia, King’s Printer, Victoria BC, 1944, p. 1.

[37] Report of the Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology for the Year 1944. p. C9. RBCM Ethnology Collection Files. I owe this reference to Grant Keddie.

[38] AR to AW, 1 August, 1941

[39] AR to F.B. Ashbridge, 4 August, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, File 2/3, BCA

[40] AR to G. Clutesi, 4 August 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, File 2/3, BCA

[41] AR to AW, Aug. 12, 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[42] BN to AW, 25 March, 1943, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL. It’s likely that Ravenhill helped sell a few paintings for Clutesi. A couple of years later Betty Newton informed Walsh that she had been able to sell Clutesi’s painting of the lightning snake, and he had given the money to the Indian Spitfire Fund. Clutesi credited Walsh with having had an encouraging influence on his art after the two met at Alberni in the spring of 1943. Ravenhill (who brought them together) is not mentioned.

[43] AR to AW, 1 August, 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[44] AR to DM, 3 December, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[45] AR to AW, 11 February, 1942, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[46] AR to F. Burling, 8 April, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[47] AR to AW, 27 June, 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[48] Daisy Millar [DM] to AR, 18 April, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, File 2/3. BCA

[49] AR to Albert Millar [AM], 10 May, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA. The reference to “cumberers of the ground” refers to the negative attitude of many Victoria residents (and settler British Columbians generally) to Indigenous peoples, although it should be noted that the reception to Sis-hu-lk’s art was very enthusiastic in Victoria.

[50] AR to DM, 30 April, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[51] DM to AR, 18 April, 1941, Add. Mss., Box 1, File 2/3, BCA

[52] S.F. Racette, “I want to call their names in resistance”: Writing Aboriginal women into Canadian art history, 1880-1970, in K. Huneault & J. Anderson, Rethinking Professionalism: Women and Art in Canada, 1850-1970 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston, 2012). pp. 285-326.

[53] Elizabeth Renyi immigrated to Canada in 1929 from Hungary at the age of 15. After her writing ventures with Inkameep, she worked as a secretary and became a columnist for the Oliver Chronicle after retirement. See “Tribute to Elizabeth Anne Renyi Kangyal Minns, 1914-2010,” Okanagan Historical Society, Vol. 75, 186-187, 2011.

[54] Isabel Christie MacNaughton (known as “Buddie”) was a well-known community worker in Oliver for her entire adult life. See http://www.memorybc.ca/macnaughton-isabel-christie-1915

[55] Walsh to AR, 29 November, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[56] D. Millar to AR, 7 February, 1942, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[57] AR to DM, 13 February, 1942, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[58] See a recent biography of Thornton. Sheryl Salloum, The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton, Mother Tongue Publishing Limited, Salt Spring Island, 2011.

[59] Walsh to AR, 17 September, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[60] Lawren Harris to AW, 31 May, 1941 , Anthony Walsh fonds, UBCSCL

[61] AR to Albert Millar, 22 November, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCARS

[62] AR to AW, 19 November, 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL.

[63] AR to AW, 7 July, 1943, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] AR to DM, 10 December, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCARS

[67] AR to AW, 5 June, 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[68] NS to AR, 1 February, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[69] R.A. Hoey to AR, 21 October, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116 Box 1 BCA.

[70] NS to AR, 7 Novemer, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[71] AR to Albert Millar, 7 November, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[72] AR to Hoey, 8 December, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[73] Ibid.

[74] AR to Dr. Carl, 17 February, 1942. GR-0111, Box 16, File 27, BCA

[75] Suggestions on the Encouragement of Arts and Crafts in the Indian Schools of British Columbia. October, 1942. Society for the Furtherance of B.C. Indian Arts and Crafts. LAC [75] RG 10, File 41203-1. The paper is written on the letterhead of the Society and is signed by Ravenhill as President.

[76] Native Canadians: A Plan for the Rehabilitation of Indians. Submitted to The Committee on Reconstruction and Re-establishment, Ottawa. Okanagan Society for the Revival of Indian Arts and Crafts, Oliver, BC. MS 1116, Vol. 2, File 1, BCA.

[77] Ibid., p. 3.

[78] Ibid, p.8.

[79] Ibid, 10. There were deeply harmful, unethical issues at work. See Ian Mosby, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools”, 1942–1952, Histoire sociale/Social history, Vol. 46, no. 91, May 2013.

[80] Recommendations submitted by the Okanagan Society for the Revival of Indian Arts and Crafts of Oliver, B.C., June, 1946, to the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons to examine and consider the Indian Act. Anthony Walsh files, Add. Mss. 2629, Box 1, File 22, BCA.

[81] Aboriginal people did get voting rights for the 1949 Provincial election, but the Federal vote was not granted until 1960. See http://www.elections.bc.ca and http://www.elections.ca.

[82] A History of Indian and Northern Affairs. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Gatineau, QC, 2011. I https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1314977281262/1314977321448. www.ainc-inac.gc.ca

[83] Ibid., p. 8. See also http://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=res&dir=his&document=chap3&lang=e

[84] AR to AW, 12 December 1942, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[85] AR to AW, 22 May 1943, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[86] AR to AW, 11 December 1943, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[87] Ibid.

[88] A. Walsh, “The Inkameep Indian Day School.” Okanagan Historical Society Thirty-Eighth Annual Report, 14-20, 1974.

[89] Thomas Fleming, Lisa Smith and Helen Raptis, “An accidental teacher: Anthony Walsh and the Aboriginal Day schools at Six Mile Creek and Inkameep, British Columbia, 1929-1942,” Historical Studies in Education, Spring, 1-24, (2007), p. 15.

[90] L.M. Smith, Portrait of a teacher: Anthony Walsh and the Inkameep Indian Day School, 1932-1942. Thesis (M.A.) University of Victoria, 2004, p. 75.

[91] A. Dalyrumple, “On the Farm: BC Teacher returns from study in South,” The Vancouver Daily Province, 4 October, 1947. Add. Mss. 1116, box 2 file 4, BCA.

[92] Racette, “I want to call their names in resistance”, p. 309.

[93] See a charming story about Baptiste in this reference. M. Baillargeon and L. Tepper, Legends of our Times: Native Cowboy Life. UBC Press, Vancouver, 1998, p. 191.

[94] AR to AW, 4 August 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[95] AR to Daisy Millar, 4 August 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, File 2/3, BCARS

[96] AR to AW, 23 August 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[97] AR to AW, 27 August, 1941, Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL Ravenhill was a few years older than Gibbon at this time.

[98] Ibid.

[99] AR to NS, 15 December 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[100] J. Cleveland Belle to AR, 18 March, 1942, LAC RG 10, File 41203-1

[101] AR to Hoey, 15 April, 1942, LAC RG 10, File 41203-1

[102] Attempts to locate the archives of the Cotton Board have so far been unsuccessful. Somewhere in England might still be a dusty envelope full of the samples prepared so thoroughly by Ravenhill.

Leave a Reply