Chapter Five

December 15th, 2016

Meeting Mr. Coyote

“Oh good, it’s Friday” Clarence Walkem[1] said to his best friend, Oliver Stewart. It had been a long week at St. George’s Indian Residential School. “What’re you going to draw today?

“I liked those bucking horses we did last week,” Oliver said. Then he stopped a minute. “How come we only get to draw on Fridays? And how come we only get to go to school for half a day? We’re just giving free labour around here.”

“I guess you mean being a farm-boy,” Clarence said.

“And cannery-boy and boiler-boy. And the worst is barn-boy. Two and a half hours of stinky pig pens.”

“You have to admit that being the collector for the church service is pretty good.” Oliver smiled a little. He was famous for his deadpan look and ability to take loose change out of the collection plate every Sunday. It served the Principal right, not to get every last penny out of the St. George’s kids.

“Come on,” he said to Clarence, “We have to line up for breakfast.”

There were so many numbers and lines at St. George’s. Clarence had learned this on his very first day from his older brothers Stanley and Bert. “Don’t forget number 432,” Stanley told him. “That’s who you are now. See, it’s on your overalls, and your socks and night gown.”

Bert taught him about the dining room lines. “Before supper we have to go to the boys’ basement and make three long lines that’re six feet apart.”

“Which line do I go in?” Clarence didn’t want to do the wrong thing.

“You just come with me in my line,” said Stanley. But it was the wrong line and the “Supe” (that stood for Superintendent) made Clarence go into the first line. The Supe ordered, “Stand at ease, attenshun, left turn, forward march!”

Clarence and seven other small kids marched into the dining room with two big boys, one in front and one behind them. The girls came in from the other side of the room in the same way. At the top of each table the eight kids divided into two fours on each side of the table with the big boys at each end. It was like a herd of cattle neatly splitting into two groups to go around a tree. Clarence slung one leg over the bench to sit down, but the kid beside him hissed, “Wait till after ‘Grace’!”

Ten tin cups, ten tin plates, ten pieces of cake and ten forks were set out on each table. The older boys stood at the ends of the tables and doled out potatoes and stew, the kids passing the plates down. “Get on the good side of the ‘enders’,” Clarence’s brothers had told him. “They’ll get you extra food. But if you tell on somebody, you’ll be sorry. You’ll get less.”

Clarence noticed a table full of adults at the front. “That’s the staff table,” whispered the boy beside him, who turned out to be Oliver. “See, they get pie.” At the end of the meal, the Supe said, “Quiet, Stand, Grace,” and the kids filed out.

School wasn’t fun. His dad had wanted to send him to public school, but Clarence wanted to go to St. George’s because Bert and Stanley were there. “You’ll have lots of kids to play with,” Bert said.

Finally when Clarence turned seven years old, his parents let him go. The only fun time in the whole week was Saturday afternoon when the kids were finally free. Wherever they went there were always range cattle to be rounded up and the calves and yearlings ridden. One time Clarence fell off and got hurt, but he told the Supe he fell out of a tree.

Clarence couldn’t remember any of the St. George’s teachers clearly. Some were strict and some were easy, but all of them had one thing in common; they were always right.

Clarence admired how Oliver resisted the rules of the residential school. Oliver never bawled when he was strapped, he never pulled his hand away and he always kept his eyes hard on the principal’s. “The Principal thinks we’re only fit to be blacksmiths,” Oliver said. “So I’m going to ask for a whole day of education instead of working half a day on the grounds. Who are we working for anyways?”

At first no one took Oliver’s determination seriously, but finally one of the teachers rounded up all the books that weren’t too far out of date and even bought some for Oliver. In one year Oliver completed grade seven, eight, and half of grade nine, and then he left the residential school. “I’ve had enough of this jail,” he told the Principal.

Oliver’s parents wanted him to continue his schooling and he finished half of grade eleven at the public school — then he quit there too. Maybe he went rodeoing — that’s what they did in those days.

* * *

Another initiative under the auspices of the Society combined several aspects of Alice Ravenhill’s interests in Indigenous legends, children’s art, and possible art prodigies. In November and December of 1940, two articles by Noel Stewart, a teacher at St. George’s Residential School in Lytton, appeared in the Vancouver Daily Province as “Students of Lytton School tell legends of their people” and “Indian Children’s Story of the Nativity.”

The articles featured the artwork of Reynold Smith, an eleven-year old student at St. George’s. The Nativity drawing featured an angel, a baby on a papoose board hanging from a tree, and three coyotes bearing gifts.[2] Alice Ravenhill must have written to Noel Stewart inquiring about Reynold Smith shortly after the articles appeared because he replied that Smith was only one of his good artists: “There are six very outstanding pupils in my class of 34.”[3] His students had a deep pride in the stories: “After hearing the legend they want to draw illustrations for them. I never give them any help in the drawing though I have suggested changes in the setting.”[4] He ended his first letter with a hearty compliment for Ravenhill: “Anyone who is working like you are to revive the arts, crafts or legends is doing a marvellous piece of work.”

Ravenhill and Stewart began to correspond frequently. He had previously taught at Alert Bay Indian Day School and before that, at Indian Residential Schools at Hazelton and Cardston, Alberta. Stewart made it clear that he used artistic license in the writing: “I make my characters actually live,” he wrote to Ravenhill, “[and] it may reduce the legends point of view.”[5] An example of Stewart’s interpretation efforts can be seen in a wooden plaque that he sent to Ravenhill with the following description:

[The picture] is of Mr. Coyote taking his Sunday Service. Please note how heartily the Coyotes are singing. The choir of 8 golden birds came from Heaven to each meeting. These birds were great singers. They were taught to sing in Heaven and they taught the Animal People on earth. After each service they returned to Heaven.[6]

Stewart complimented Ravenhill on Native Tribes – which seems to indicate the extent to which the book had been distributed in British Columbia. In turn Ravenhill lamented to Stewart that she had hit a roadblock with her next project. “I can’t get a publisher to issue a collection of the legends of this Province I selected from the hundreds hidden in the archives.”[7]

Stewart replied that he and his boys had prepared a booklet of about thirty-five stories on the Animal People in the fall and had sent them to an American publisher.[8] This horrified Ravenhill: “It seems to us a thousand pities to give to wealthy America this early fruit of B.C. Indian art, to which we urgently need to draw attention.” Would he be interested, she asked, in a booklet to sell for twenty-five cents in paper cover, “with some such title as ‘Meet Mr. Coyote’?”[9]

As it happened, the American publisher rejected a story about the purification ceremony of the Thompson tribe. “This is a true enough custom,” Stewart wrote to Ravenhill. “Even our old Indians today still believe in a yearly washing of sins. [The publishers] also desire other evidences of which I regard as ridiculous.”[10] He put together ten legends and drawings and sent them off to Ravenhill.

Thus Meet Mr. Coyote was born.

Ravenhill committed the Society to print one thousand copies. At the last moment before publication she informed Stewart that she wanted to omit the names of the five boys who drew the pictures. “The public is so careless in its superficial reading that the names ‘Jimmie Johnson,’ ‘Dan Phillips’ etc. would be accepted as those of white Canadians.”[11]

Stewart responded by return mail with the “Indian” names that he said the boys had immediately chosen for themselves. Jim Johnston became Wah-und (“quick”); Reynold Smith, Moo-mah (“bright”); Joe Dunstan, Sis-malt (“good-looking”); Oliver Stewart, Che-ma (“like a white boy”) and Willie Spuzzum, Spup-aza (“old in ways”).[12]

Ravenhill wrote the foreword in which she introduced Mr. Coyote as: “A great leader among the Animal People in the misty far-off days, ages before white men came to disturb the old customs:”

To meet Mr. Coyote is quite an adventure as you will agree when you have read about some of his good deeds. There still remain a very few, very aged folk who could tell you what their grandparents told them about how he taught their forebears.[13]

Ravenhill acknowledged the boys who wrote the stories and also Noel Stewart, “their sympathetic teacher,” who encouraged the students to draw these “happy pictures ‘out of their heads.’”[14] The stories presented a kind, gentle Coyote, somewhat different from other portrayals.[15] The drawings made the book particularly attractive. Who could resist a trio of coyotes sitting around a campfire smoking sacred tobacco, or Mr. and Mrs. Coyote on a friendly walk with Brother and Sister Skunk?

Anthony Walsh was very appreciative of Stewart’s work. “I saw Mr. Coyote,” he wrote to Ravenhill, “and fell very much in love with him. The illustrations are delightful, and the legends very cleverly told. I also liked your remarks, so clear, charming and enlightening. I feel sure it will have a good sale.”[16]

Stewart personally sold at least 100 copies up and down the Thompson Valley. Anxious to ensure that his students were recognized for their work, he reminded Ravenhill that the book was made more saleable because the boys had a hand in the pie: “In fact so many people have written for more details of these boys. They seem to want to make certain we are not just using the boys [sic] names without justification.”[17]

When Noel Stewart first started working on Meet Mr. Coyote, the Reverend Adam Ralph Lett was Principal at St. George’s. Stewart found Lett to be supportive of his art endeavours, “though of course he doesn’t understand ‘Art’ or delve into the legends as I’d like him too, he says he has no objections to my doing as I desire.”[18]

When Lett retired in July of 1941, Stewart was appointed Acting Principal and hoped that he might be asked to take over the position. After Dr. Harold McGill, the Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, visited St. George’s in September of 1941, Stewart wrote proudly to Ravenhill, “I have had the place cleaned up really well, and all the rules put into force which in my estimation are the correct ones for running a school.”[19]

But Stewart was not appointed. The Anglican Church maintained a policy of putting only clergymen into the principalships of residential schools. “I don’t see why these places should have a clerical head anyways,” he told Ravenhill. “After all we are instructing children, and why use a parson for it. We would not send a white child of 6 to 15 to the parson for all his religious teaching etc.”[20]

Stewart expressed a great sense of caring for the children’s welfare during his two months as acting principal. He wrote directly to Major McKay, the Indian Agent, asking for new clothing for the children because they were “practically in rags,” and he reported a serious lack of dining room utensils.[21] The Indian Affairs Branch [IAB] agreed to order clothing, but left the choice of cutlery up to the new Principal, Reverend Charles Hives, appointed in October of 1941.

Coming from the well-known Shingwauk Residential School at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Hives declared that he wanted to replicate that school’s structure at St. George’s.[22] “New principal Mr. Hives has been 25 years in Indian work, so I don’t suppose will be too keen over my modernistic Art and Craft ideas,” wrote Stewart. He was still full of hope, however, describing a film that was in the wind, and how the boys proposed to get hold of a cereal foods company to use the coyote images in their packaging.

Noel Stewart considered that he had a special gift for working with his young charges. “I see the good in all,” he wrote.[23] When Ravenhill met Stewart after three years of letter writing, she was disappointed to find him high strung, self-conscious and rather plump, but as she wrote to Anthony Walsh, “His heart is in Indian work…. He seems to win Indians’ confidence and brings zeal with him; aware how much he can gain as well as give.”[24]

Hives was a disaster for Stewart’s tenure at the school. In his capacity as the BC Inspector of Indian Schools, Captain Gerald Barry visited St. George’s shortly after Hives had taken over. Stewart gave Ravenhill details of their meeting:

Between OURSELVES Capt. Barry was here this week, and he and our new Head collided. They had a rather miserable time of it, I am afraid that Mr. Hives has made a poor start, no matter how he may try now, Capt. Barry won’t forget things. Capt. Barry wanted me to resign at once, and leave for Metlakatla, but when I asked the boys later if I could go they all broke down, and after thinking it over, I felt I should try and hang out for their sake this term.[25]

The Metlakatla Day School, up on the North Coast by Prince Rupert, might have been a good idea. Noel Stewart struggled constantly with the constraints of the Residential School system. “I’m only a pivot in a wheel,” he wrote. “Res Schools are not the Day Schools.” [26] He expressed empathy for his young charges, writing to Ravenhill, “Some of this Res school life is hard on the kiddies (I think). I often wonder how we would re-act if in their shoes.”[27]

Walsh described what Stewart was going through at St. George’s as a type of “purgatory:”

I have also had to face many like problems, so can fully sympathize with him. The reception that the book gets should hearten him, and this opposition may be a blessing in disguise, in that he may return to day school work, where he will have much more freedom of action. [28]

Meet Mr. Coyote was indeed a source of pride for Noel Stewart. While A.E. Pickford wrote that Stewart deserved credit for his work of “tapping a pictorial source at its clearest and best: that is while the latent feeling engendered in the mind of the Indian child by the mythology of his forefathers is still unclouded,” he also noted that Stewart was out of harmony with James Teit’s accounts.[29] To Ravenhill, Stewart disputed these conclusions: “My pupils here love their legends but they did not know any of them until I dug them up this fall.”[30] As for misinterpreting Teit, Stewart referred to an issue of Teit’s legends collection, “which shows we agree quite a lot.”[31]

Stewart wrote that he was sent out to walk each afternoon with the older boys. “We usually get to the big hill overlooking Lytton. This is the happiest duty of the day, since the boys (like myself) are so glad to get away from the premises for a while.”[32] Such trips were the calm before the storm.

The stress at St. George’s continued. The newcomer Hives immediately cancelled Christmas leave for both teachers and students, and animosity began to build. Before long, the cook and three teachers (one of whom was Edith Walkem, the first Indigenous person to graduate from Normal School in B.C.) had left St. George’s. The inflexible Hives forbade Stewart to have his students make Christmas cards for sale: “Not one bit of craft work has been done since [Hives] came and he is just in a terrific confusion — blaming everyone but himself.”[33]

In January of 1942, Stewart finally resigned from St. George’s and vowed to take his students’ work with him. He obtained a teaching position in a public school at Spence’s Bridge, forty kilometers further up the Thompson valley, and wrote to Ravenhill explaining his reasons for leaving: “The principal of St. George’s in my estimation is only a brute and not fit to be in charge of so many fine boys and girls. Whatever the govt. may think of him can only be from the fact they don’t really know him. I am truly sorry for the kiddies under his vile leadership.”[34]

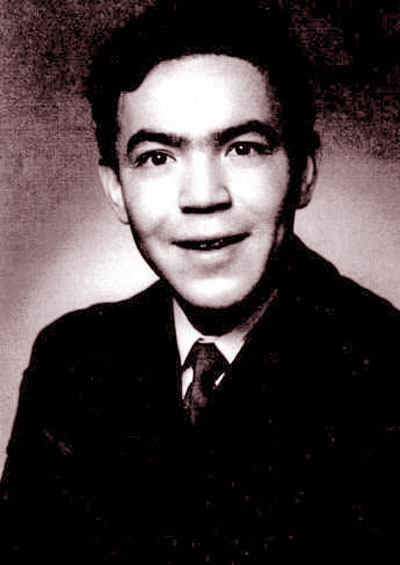

Stewart tried his best with what he called the “wild whites” at Spence’s Bridge. “I can still do good,” he wrote to Ravenhill. “The Indians of this valley seeing me here keep asking me why did I leave their boys at Lytton and come here. I daren’t tell them truth why or they’d probably demand their children from there — like the Walkems did.”[35] Clarence Walkem, brother to Edith, had followed Stewart to the Spence’s Bridge school. Stewart considered Walkem to be the finest student he ever had, “full of life and humor.”[36]

Stewart also wanted to get Reynold Smith out of St. George’s. “He is too fine for Hives,” he wrote. Whether or not that happened is unknown. Stewart did not find another group of students with the talents of his St. George’s boys. A year later, Ravenhill remarked on Stewart’s complete breakdown in health. “I urge him not to give up hope,” she wrote, “again and again in my long life I have regained ability to work when doctors told me to the contrary; but I do not know the cause of his ill-health so it behoves [sic] me to be careful in trying to infuse hope.[37]

Art education did not continue at St. George’s School to any measurable extent after Stewart’s departure in 1942. He had sent some of his boys’ work to Ravenhill, and she had donated it to Dr. Clifford Carl at the Provincial Museum along with the following comment: “I am sending up the three small panels I possess from the clever boys at St. George’s School Lytton which they deserve to have shown, although the whole work is at presently absolutely at an end, and most of the boys have left and are just slouching around doing nothing.”[38]

Noel Stewart resurfaced again in 1948 in a collaborative project with Anthony Walsh with suggestions for teaching art in Indian schools, but his whereabouts after that are unknown. He never received the acclaim that Walsh has, but in his way, he also broke new ground for Indigenous children’s art education.

Alice Ravenhill’s interests were not changing, but she was moving on to a wider sphere of interest.

[1] This narrative is drawn from a paper written for a UBC Sociology class by Clarence Walkem in which he relates his experiences and others’ students at St. George’s Indian Residential School at Lytton, B.C. See Clarence Walkem, 30 March, 1953, “Life of an Indian Lad in a Residential School.” ADD Mss. 2327, BCA

[2] See “Boys and Girls Corner,” The Vancouver Sun, 30 November and 7 December, 1940, p. 12, “Students of Lytton School tell legends of their people,” 30 November, 1940, p. 22, and “Indian Children’s Story of the Nativity,” 14 December, 1940, Sect. 3, p. 4, both in The Vancouver Daily Province. All bylines were by Noel Stewart.

[3] Noel Stewart [NS] to AR, 15 December, 1940, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[4] Ibid.

[5] NS to AR, 7 January, 1941. Add. MS – 1116, Box 1, BCA

[6] The plaque, or one that meets the description, may be seen at the RBCM’s Ethnology Collection in Victoria.

[7] AR to NS, 18 December, 1940. Add. MS – 1116, Box 1, BCA

[8] NS to AR, 21 December, 1940. Add. MS – 1116, Box 1, BCA

[9] AR to NS, 3 January, 1941. Add. MS – 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[10] NS to AR, 7 January, 1941. Add. MS – 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[11] AR to NS, 6 November, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[12] NS to AR, 7 November, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[13] A. Ravenhill, “Introduction to ‘Meet Mr. Coyote’”, (n.d. c. 1941), Victoria Branch of the Society for the Furtherance of B.C. Tribal Arts and Crafts, pp. 3-4.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ror a discussion of the meanings of Coyote, see Jo-ann Archibald, Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit, UBC Press, 2008, pp. 5-11.

[16] AW to AR, 29 November, 1941. Add. Mss. – 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[17] NS to AR, 28 February, 1942, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[18] NS to AR, 1 February, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[19] NS to AR, 4 September, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[20] Ibid.

[21] NS to D.M. MacKay, 3 October, 1941, LAC RG 10, File 41203-1

[22] NS to AR, 28 October, 1941. The Reverend Charles Hives had mixed reviews from his years at Shingwauk. See http://www.shingwauk.auc.ca/Memories/Sands/Sands_story.html

[23] NS to AR, 16 February, 1942. Add. Mss.1116, Box 1, BCA

[24] AR to AW, 26 October, 1943. Alice Ravenhill fonds, Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[25] NS to AR 19 November, 1941, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[26] NS to Alice Ravenhill, 21 December, 1940. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[27] NS to AR, 29 December, 1940. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[28] AW to AR, 29 November, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA.

[29] A.E. Pickford, “Meet Mr. Coyote,” a series of B.C. Indian Legends (Thompson Tribe), The Northwest Bookshelf, January, 1942, pp. 70-71. James Teit was Franz Boas’s most able research assistant. See J. Thompson, Recording their Story: James Teit and the Tahtlan, Douglas & McIntyre; Vancouver and Toronto, 2007.

[30] NS to AR 15 December, 1940, Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA. This lack of knowledge could be directly attributable to the separation of children from families through the residential school system. Like Walsh’s insights into the importance of drama for his students, Stewart understood intuitively the importance of the legends project to reach his students.

[31] NS to AR, 9 January, 1942. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[32] NS to AR, 30 December, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[33] NS to AR, 30 December, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[34] NS to AR, 6 February, 1942.Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[35] NS to AR, 14 February, 1942. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA

[36] NS to AR, 1 February, 1941. Add. Mss. 1116, Box 1, BCA. Interview with Verna Miller, niece of Clarence Walkem, September 4, 2007. Walkem was the first Indigenous person to graduate from UBC. According to his niece, Verna Miller, racial stereotyping kept him out of veterinary school.

[37] AR to AW, 22 May, 1943. Alice Ravenhill fonds. Box 1, File 8, UBCSCL

[38] AR to Clifford Carl, 2 May 1942, GR-0111, Vol. 16, File 27, BCA

Thank you for your email. I’m hoping to get back to Alice Ravenhill this year. Mary Leah de Zwart maryleah(at)shaw.ca

Very good information on St George’s. I went to sgs when Canon Hives was the principal.